Last updated: February 7, 2024

Article

From Buffalo Soldier to Bath Attendant: The Story of Hugh Hayes and Hot Springs National Park

Courtesy of Kelly Reese

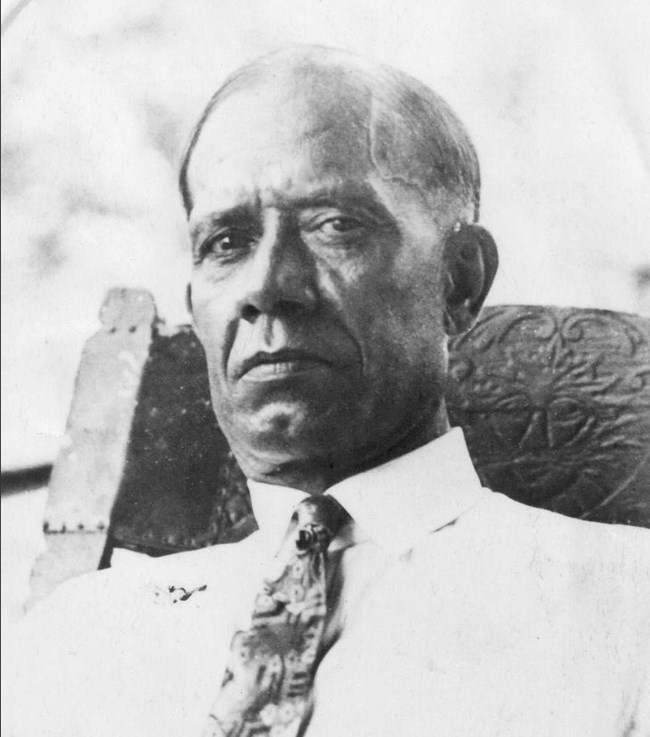

The reason for the letter was simple: Hayes, while working as an attendant in Hot Springs for the past decade, was concerned he would be unable to pass these new exams. Years earlier a horse fell on him, leaving Hayes “a little lame in one foot.”1 The location and occupation of Hayes’ accident made this admission more significant, however. He injured himself at Fort Assiniboine in Montana as a member of the 10th United States Cavalry Regiment. Hugh Hayes was a Buffalo Soldier.

Courtesy of Montana State Library

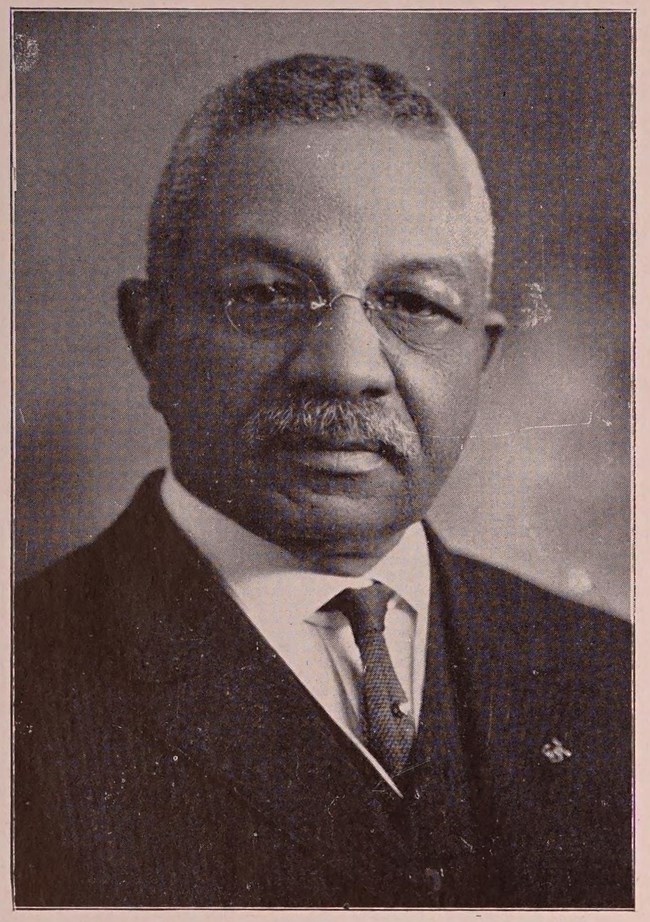

After his military career, Hayes began a new one at Hot Springs National Park. He visited Hot Springs in the 1890s and witnessed the opportunities present for African American men and women working as bath attendants. These individuals fueled the bathing industry in Hot Springs and made lucrative livings as indispensable members of bathhouse businesses. Hayes’ time in Hot Springs brought him in contact with some of the more influential African American citizens in the town.

Hugh Hayes was an ordinary man who participated in extraordinary moments in history. His story not only serves as an example of singular achievements through systemic challenges, but it also connects the history of Hot Springs National Park to seemingly unrelated moments in American history.

“Ready and Forward”: Becoming a Buffalo Soldier

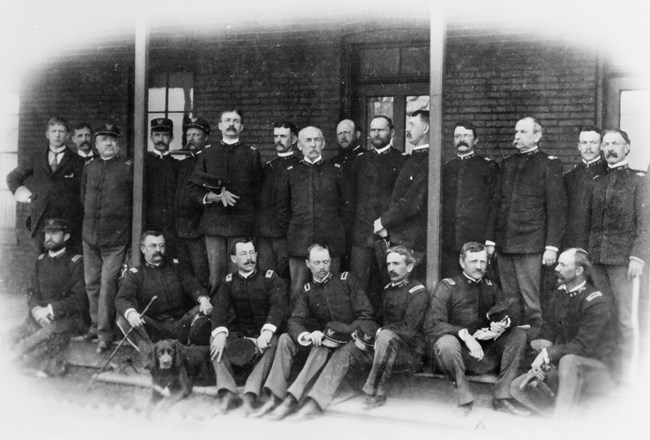

Hugh Hayes was born on October 11, 1877. While he was able to read and write, Hayes did not attend school in his hometown of Dresden, Tennessee. On May 25, 1896, Hayes enlisted in the Army at age 18. He was assigned to the 10th Colored Cavalry, I Troop. Hayes was joining a regiment with an already storied past.The Army created the 10th Cavalry in 1866 at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. The 9th and 10th Cavalry, as well as the 38th, 39th, 40th, and 41st Infantry regiments were products of the 175,000+ African American men who fought for their freedom during the Civil War. The 10th Cavalry’s motto was “Ready and Forward” With the men performing many frontier duties such as protecting mail routes, building roads, and locating natural resources like drinking water.

Frederic Remmington

The romantic myths surrounding the Buffalo Soldiers are complicated. Confronted by a rapidly segregated and violent society for African Americans in the late nineteenth century, these men found a semblance of freedom and independence in the Army. But they found that independence in a system designed to erase Indigenous groups from their ancestral homelands.3

Courtesy of Montana State Library

Hot Springs National Park Archives

The Spanish-American War

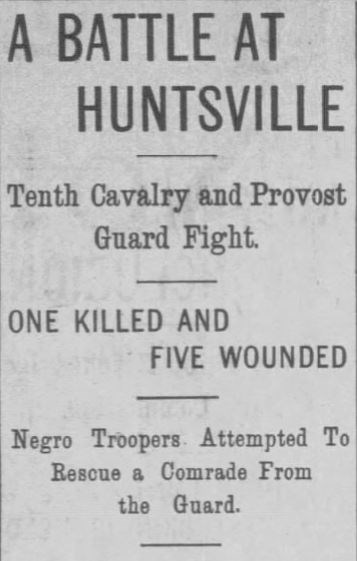

While Hugh Hayes recovered in a hospital bed, the U.S.S. Maine exploded in Havana, Cuba, on February 15, 1898. Officials in the United States used the event to enter a war with Spain for control of territories in the Western Hemisphere. Individuals in and out of the War Department believed, in an era dominated by Eugenics and medical knowledge mixed with racial difference, that African American soldiers could handle the tropical climates of Cuba better than their white counterparts.7Hugh Hayes rejoined the 10th Cavalry after they relocated from northern Montana to Chickamauga, Georgia, to train for their role in Cuba. In the South, many white residents were anxious and threatened seeing African American soldiers “armed with pistols, sword bayonets, and circled with cartridge belts, with every thimble filled with cartridges.” Racial confrontations ensued during the regiment’s two-month training stint in Georgia.8

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

It does not appear Hayes fully recovered from his injuries as he remained in the United States to serve as a reserve force and ensure supply lines remained intact.9 In Cuba, the 10th Cavalry served as the leading edge during the most significant fighting on the island, participating in battles at Las Guasimas, El Caney, as well as Kettle Hill and San Juan Hill. At San Juan Hill, the 10th Cavalry reestablished positions after a chaotic charge by Lieutenant Colonel Theodore Roosevelt and his Rough Rider regiment of the 1st Volunteer Cavalry. Roosevelt described the victory as a “very great confusion” with “different regiments being completely intermingled – white regulars, colored regulars, and Rough Riders.”10

Roosevelt initially dismissed the skill and courage of the Buffalo Soldiers, calling them “shirkers in their duties.” He was quickly rebuffed by 10th Cavalry Trooper Presley Holliday, calling Roosevelt’s assessment “uncalled for and uncharitable.”11 Roosevelt appeared to change his stance by the time he was President of the United States. Delivering a speech in 1903, Roosevelt said, “I fought beside the colored troops of the 9th and 10th Cavalry. If a man is good enough to have him shot at while fighting beside me under the same flag, he is good enough for me to try to give him a square deal in civil life.”12 Subsequent scholars have highlighted the significance of the 10th Cavalry in American successes in Cuba.

Chattanooga Daily Times

Working as a Bathhouse Attendant

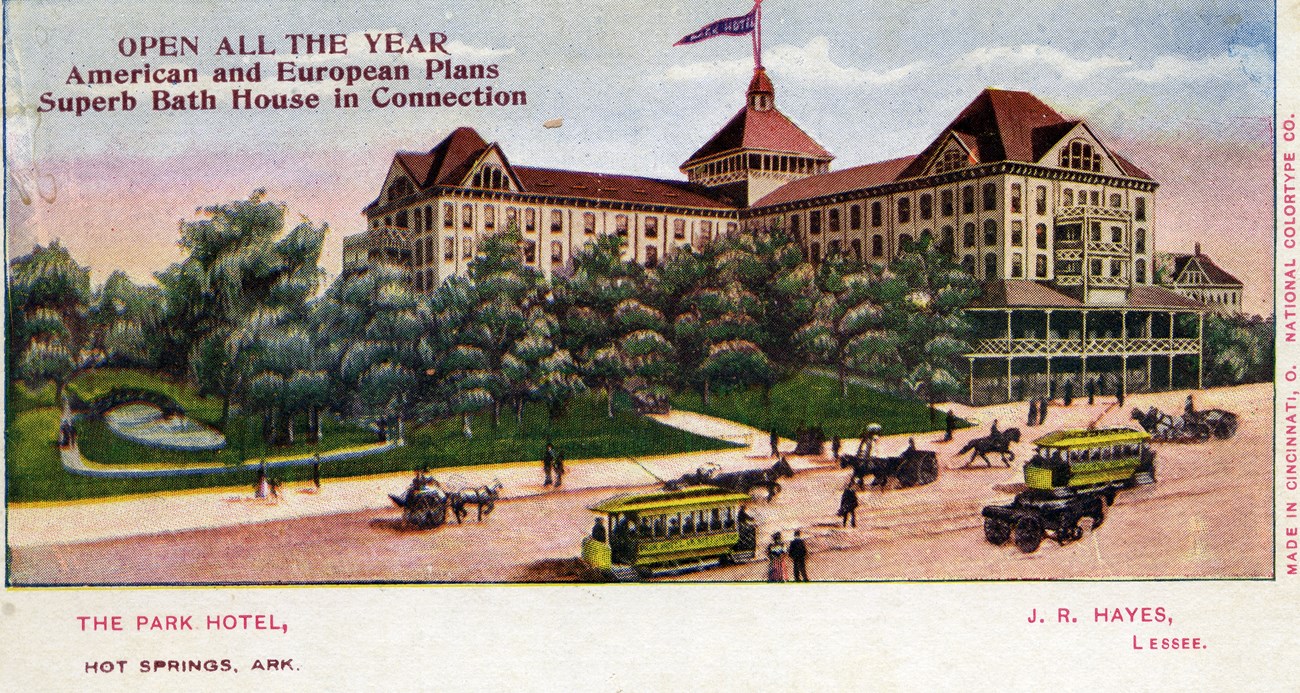

It is unknown how or why Hugh Hayes returned to Hot Springs around 1903, but his stay at the town’s Army and Navy General Hospital likely introduced him to the opportunities open to an African American man in town. In 1898, bathhouse attendants, according to Hot Springs’ Superintendent William Little, “are well paid for the labor performed as any other class of people.”16 By the beginning of the twentieth century, African American bathhouse attendants made themselves indispensable parts of the bathing industry in Hot Springs. They began to organize to protect their pay and professions from exploitation. And in 1903, residents secured the first bathhouse used exclusively by African Americans.Hugh Hayes began working as a bath attendant at the Park Hotel Bathhouse, an establishment with a national reputation. By the early 1900s, Hot Springs Reservation situated itself as the nation’s premier thermal water health resort. Publicity for Hot Springs’ bathhouses appeared in local and national medical journals across the country. The Park Hotel advertised itself to the elite class of patients and patrons who visited Hot Springs, sporting rooms lit by electric light. It also declared it had “THE MOST ELEGANT BATH HOUSE IN THE COUNTRY” with some of the latest hydrotherapy treatments of the era like needle showers and electric baths.17 Hayes and and his fellow bath attendants offered thousands of baths to visitors at the Park Hotel. For example, in 1907, the bathhouse provided 22,404 baths, just under the average of 27,764.

Hot Springs National Park Archives

Clement Richardson, The Cyclopedia of the Colored Race

With this infrastructure and workforce, Hugh Hayes quickly learned how to excel in Hot Springs’ bathing industry. It does not appear that Hayes lived permanently in Hot Springs between 1903 and 1910. He traveled back and forth between his hometown of Dresden, Tennessee, a town near the Missouri Pacific railway lines that ran through Hot Springs. Hayes worked during the peak season in Hot Springs (January – May) and then returned home. During his stint as a bath attendant, Hayes learned the latest treatments in hydrotherapy, telling Director Hallock in his 1910 letter that he had studied literature from Dr. John H. Kellogg, director of the Battle Creek Sanitarium in Michigan.20

Hot Springs National Park Archives

Dresden Enterprise and Sharon Tribune

After the Battles and Bathhouses

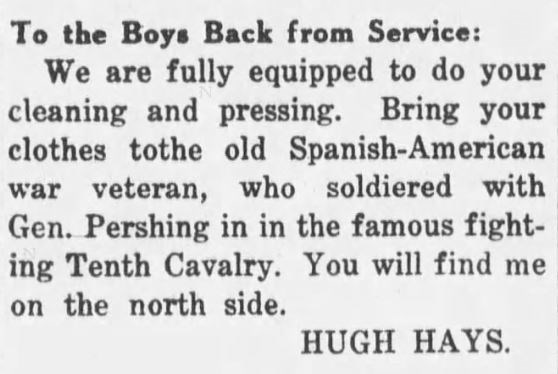

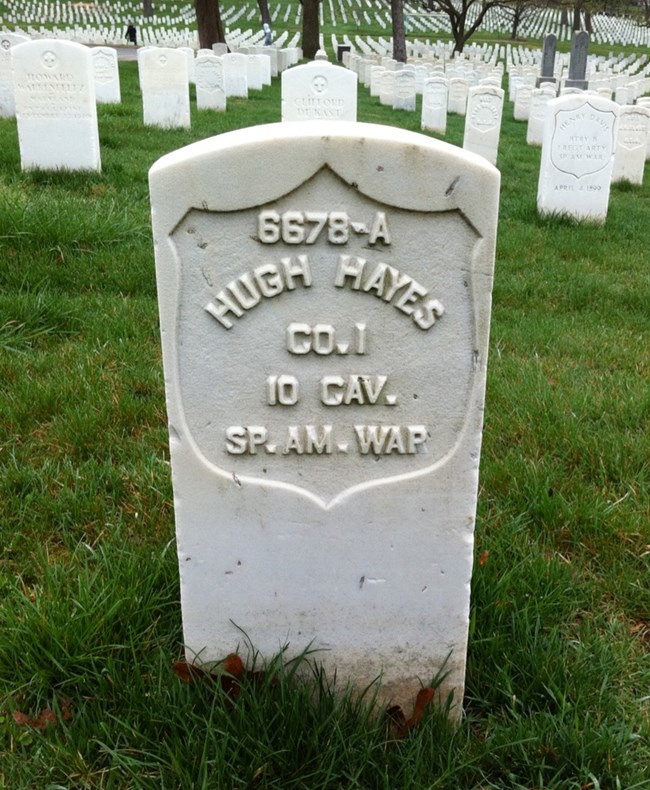

Hayes remained in Dresden, Tennessee, throughout the 1910s and 1920s. He took up a career as a presser, ironing clothes and preparing other textiles. He used his eventful past to attract customers. In December 1918, as officers and enlisted men returned from Europe at the end of World War I, Hayes placed an ad “To the Boys Back from Service” in his local newspaper, saying, “Bring your clothes to the old Spanish-American war veteran, who soldiered with Gen. Pershing in the famous fighting Tenth Cavalry.”22 Hayes ultimately became manager of the City Steam Pressing Club in Dresden.23Health Problems plagued Hugh Hayes in the latter years of his life. In 1927, he travelled to Danville, Illinois, and made the first of many visits to the U. S. National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers. Hayes continued to receive treatment for the arthritis that plagued him since his cavalry mishap in 1897. It appears Hayes moved to Illinois at some point for more routine trips to the soldiers’ hospital. On October 10, 1940, Hugh Hayes died.

Army Cemeteries Explorer, U.S. Army

Hot Springs National Park’s thermal waters attracted individuals from all walks of life. Some came to bathe in the supposed healing waters. Others, specifically African American men and women, carved out a life of service in Hot Springs by administering the waters to patients and patrons. Hugh Hayes lived a life of service. He was a Buffalo Soldier, serving in a role that gave him a sense of independence and freedom within a society where those essential rights were often withheld. He then joined a fraternity of bathhouse workers who fueled the growth of the oldest unit in the entire national park system. The thermal waters flow through the story of Hugh Hayes and millions of other stories near and far from Hot Springs, Arkansas.

Endnotes

1. Hugh Hayes to Harry Hallock, 26 October 1910, HOSP 19266, Hot Springs National Park Collection, Box 43, Series II: Concessions Records, 1879-1998, Folder 1: Bath Attendants – Training, 1910-1913, Hot Springs National Park Archives, Hot Springs, AR.2. United States Army, “Buffalo Soldiers,” U.S. Army at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, https://home.army.mil/leavenworth/application/files/2014/9979/5878/PAO-Buffalo-Soldier-Info.pdf

3. For more on the mythmaking of the Buffalo Soldiers, see Frank N. Schubert, “Buffalo Solders: Myths and Realities,” Army History 52 (Spring 2001): 13-18; Greg Martin, “Let’s Talk Honestly About Fort Missoula & Buffalo Soldiers,” 4 April 2022, Medium, accessed 25 November 2023, https://medium.com/@gregmartin_76328/lets-talk-honestly-about-fort-missoula-and-buffalo-soldiers-ef3d4190da8d

4. Richard O’Connor, “‘Black Jack’ Of The 10th,” American Heritage 18, Issue 2 (February 1967), accessed November 30, 2023, https://www.americanheritage.com/black-jack-10th

5. W. H. Carter, Major and Surgeon, U. S. Army, to Surgeon and Commanding officer Army & navy General Hospital, Hot Springs, Arkansas, 8 February 1898, Record Group (RG) 112.5.1, Records of the Office of the Surgeon General of the Army, Records of Army and Navy General Hospital, Hot Springs, AR, Entry AR-6, Case Files, 1890-1913, “Hayes, Hugh,” National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), Fort Worth, TX.

6. H. O. Perley, Patient File, “Hayes, Hugh,” NARA Fort Worth, TX.

7. LTC Roger D. Cunningham, USA Ret., “The Black ‘Immune’ Regiments in the Spanish-American War,” The Army Historical Foundation, accessed 11/30/2023, https://armyhistory.org/the-black-immune-regiments-in-the-spanish-american-war/

8. “Negro Troopers,” Chattanooga Daily Times, 24 April 1898, 4.

9. Herschel V. Cashin and Others, Under Fire with the Tenth U. S. Cavalry (New York: Arno Press and the New York Times, 1969), 348.

10. Theodore Roosevelt, The Rough Riders (New York, Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1899), 139.

11. Charles Young Buffalo Soldiers National Monument, “Buffalo Soldiers in the Spanish-American War,” National Park Service, accessed 11/20/2023, https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/busospanamwar.htm

12. “The Square Deal,” Theodore Roosevelt Center at Dickinson State University, accessed 11/30/2023, https://www.theodorerooseveltcenter.org/Learn-About-TR/TR-Encyclopedia/Politics%20and%20Government/The%20Square%20Deal

13. Willard B. Gatewood, Jr., “Smoked Yankees” and the Struggle for Empire, Letters from Negro Soldiers, 1898-1902 (Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1987), 8; in “Buffalo Soldiers and the Spanish-American War,” Presidio of San Francisco National Historic Landmark District, accessed 25 November 2023, https://www.nps.gov/prsf/learn/historyculture/buffalo-soldiers-and-the-spanish-american-war.htm

14. “A Battle at Huntsville,” Chattanooga Daily Times, 12 October 1898, 2.

15. “Hugh Hayes, 22726” The National Archives in Washington, DC; Washington, DC, USA; Historical Register of National Homes for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers, 1866-1938; Series: M1749.

16. William J. Little, Report of the Superintendent of the Hot Springs Reservation (Washington, D. C.: Government Printing Office, 1898), 945.

17. Ad for the Park Hotel, Hot Springs, AR, Hot Springs Medical Journal 2, no. 12 (December 15, 1893), 2.

18. Harry H. Myers to Secretary of the Interior, 21 September 1911, “Crystal Bathhouse” Microfiche Collection, Hot Springs National Park Archives.

19. Clement Richardson, editor, The National Cyclopedia of The Colored Race, Volume One (Montgomery, AL: National Publishing Company, 1919), 382.

20. Hayes to Hallock, 26 October 1910, HOSP 19266, Box 43, Folder 1, Hot Springs National Park Archives; see also J. H. Kellogg, M. D., Rational Hydrotherapy: A manual of The Physiological and Therapeutic Effects of Hydriatic Procedures, and the Technique of Their Application in the Treatment of Disease (Philadelphia: F. A. Davis Company, 1902).

21. Harry Hallock to Hugh Hayes, 31 October 1910, HOSP 19266, Box 43, Folder 1, Hot Springs National Park Archives.

22. Hugh Hays, “To the Boys Back from Service:,” Dresden Enterprise and Sharon Tribune, 6 December 1918, 5.

23. “Cleaning and Pressing,” Dresden Enterprise and Sharon Tribune, 28 May 1920, 5.

Tags

- amistad national recreation area

- charles young buffalo soldiers national monument

- chiricahua national monument

- fort davis national historic site

- fort larned national historic site

- fort union national monument

- glacier national park

- guadalupe mountains national park

- hawaiʻi volcanoes national park

- hot springs national park

- sequoia & kings canyon national parks

- yosemite national park

- buffalo soldier

- hot springs national park

- segregation

- medical history

- indian wars

- spanish-american war

- veterans

- hot springs

- 10th cavalry

- cavalry

- montana

- arkansas

- john pershing

- theodore roosevelt

- african amercan heritage

- african american

- black history

- buffalo soldiers