Last updated: November 2, 2022

Article

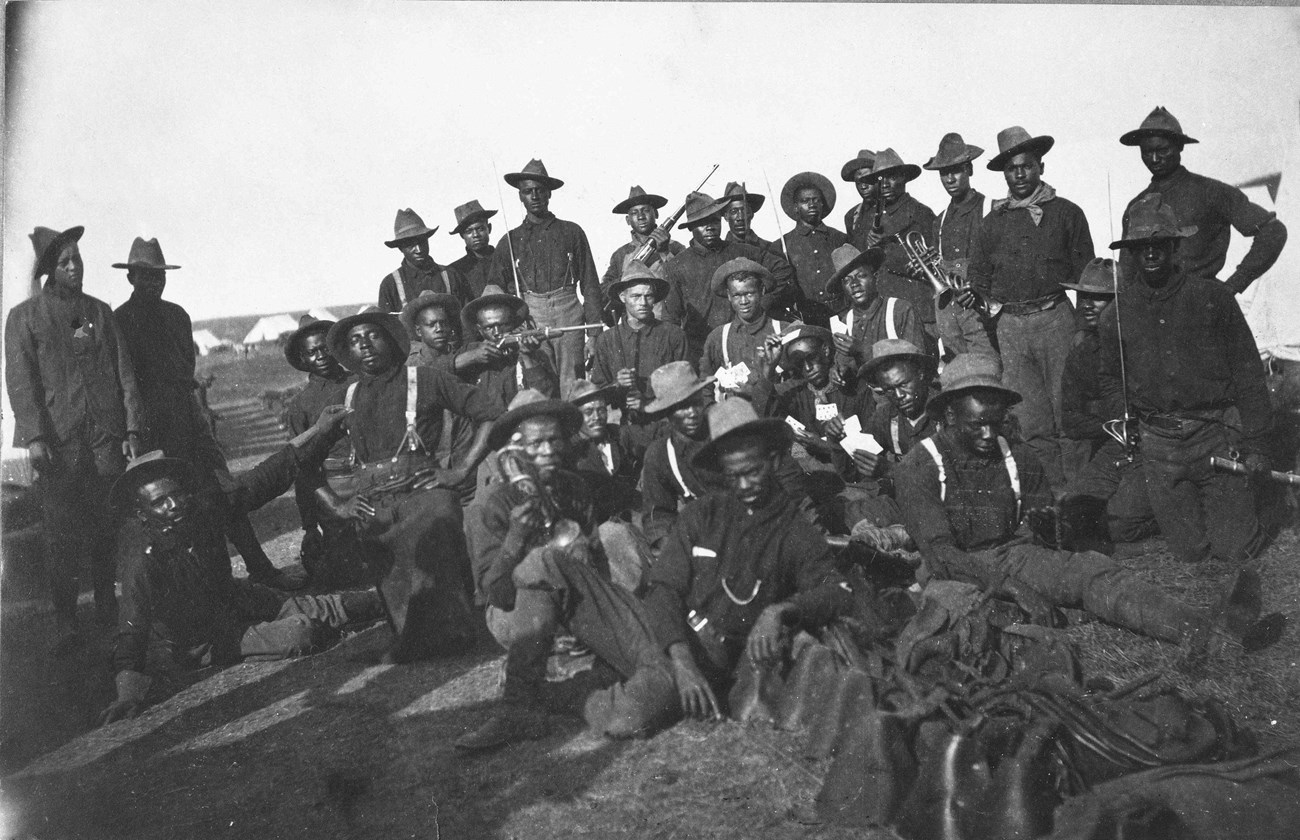

Buffalo Soldiers in the Spanish-American War

U.S. Army

In 1898, however, the outbreak of the Spanish-American War spurred the Buffalo Soldiers’ remobilization. On February 15, 250 Americans died when the USS Maine blew up and sank in Havana Harbor. Many people in government and the press blamed the deaths on the Spanish government, which was fighting to keep its overseas empire alive. The United States declared war on Spain on April 25, 1898. Americans rallied to the cause of liberating Cuba from Spain with the slogan, “Remember the Maine!”

The Buffalo Soldiers started mobilizing shortly after the USS Maine exploded. In March and April of 1898, they packed their bags and supplies and headed to Southern forts and cantonments to prepare for war with Spain. Eventually, the Buffalo Soldiers, along with white soldiers assembled in Tampa, Florida, for embarkation. While in the South and on the transport ships the Buffalo Soldiers had to endure overt racism from locals and fellow soldiers.

The U.S. Army was ordered to embark for Cuba on June 7, 1898. To the surprise of the Ninth and Tenth Cavalry, they were told to leave their horses behind and fight as infantry. The Twenty-fourth traveled to Cuba on the City of Washington, the Twenty-fifth on the Concho, the Ninth Cavalry on the Miami, and the Tenth Cavalry was split up on the Leona and the Alamo. The main flotilla of 32 ships left port enroute to Cuba.

The main American force landed near Daiquiri, Cuba, on June 22, 1898. The next day, the Americans moved landing operations to Siboney, Cuba, seven miles away, because of the area’s more suitable landing beach and infrastructure. The initially landings took several days. The war lasted a total of 113 days. The Buffalo Soldiers played an integral role in the major engagements at Las Guasimas, Tayabacoa, El Caney, and the San Juan Heights.

On June 24, just two days after the first landings an American force commanded by Major General Joseph Wheeler saw combat at the Battle of Las Guasimas. Las Guasimas was a junction between two trails about three miles inland from Siboney. Wheeler sent the First US Volunteer Cavalry, known as the Rough Riders, commanded by Colonel Leonard Wood and Lieutenant Colonel Theodore Roosevelt in one column on the left trail. Wheeler led the First Cavalry and Buffalo Soldiers of the Tenth Cavalry on the other trail that was less well marked. The Buffalo Soldiers had to hack their way through the brush.

Within 20 minutes, the Buffalo Soldiers encountered the Spanish soldiers. They exchanged gunfire, and the Americans were able to push the Spaniards out of their positions into retreat. The Americans now had a way forward toward the Cuban capital and Spanish stronghold. The Tenth Cavalry suffered one man dead and eight wounded during the battle.

The Battle of Tayabacoa was unique because it started as a special operation effort to land supplies and reinforcements. As the Tenth Cavalry was boarding transport ships bound for Cuba on June 7, 1898, Lieutenant Carter P. Johnson chose 50 troopers for a special assignment. Johnson and his group of men were headed behind enemy lines to reenforce and resupply Cuban fighters seeking liberation from Spanish rule.

On June 30, 1898, Cuban freedom fighters and some American volunteers aboard the USS Florida attempted an amphibious landing at Tayabacoa. The landing party immediately engaged with Spanish soldiers from a nearby blockhouse. The Cubans and Americans retreated, leaving behind a group of wounded comrades. A call for volunteers to rescue the wounded soldiers on the Florida began to make the rounds. After several unsuccessful rescue attempts, Private Dennis Bell, Corporal George H. Wanton, Private Fritz Lee, Sergeant William H. Thompkins, and Lieutenant George P. Ahern stepped forward and offered to rescue their wounded comrades.

The group of five soldiers went ashore and surprised the Spanish. The rescuers were able to free all the wounded soldiers, and all returned safely to the Florida. Bell, Wanton, Lee, and Thompkins were awarded the Medal of Honor in the summer of 1899 for their actions at Tayabacoa.

On July 1, shortly before the main attack on San Juan Heights, the Battle of El Caney began. This was initially supposed to be a brief engagement, but it lasted all day. The Buffalo Soldiers of the Twenty-fifth Infantry joined 6,600 other Americans in attacking El Caney. Although the Spanish soldiers were greatly outnumbered, they had strong fortified positions, including a stone blockhouse for protection.

When the Twenty-fifth Infantry arrived on the field, they saw the Second Massachusetts retreating, and the Buffalo Soldiers took their place in line. There was fierce fighting as the Twenty-fifth charged up the hill. Spanish Lieutenant Jose Muller stated that they “threw forth a hail of projectiles upon the enemy, while one company after another, without any protection, rushed with veritable fury” toward their position. The Twenty-fifth arrived at the blockhouse at the same time as the Twelfth Infantry. The Americans overran the fort and caused panic in the Spanish ranks. Private Thomas C. Butler, Company H, Twenty-fifth Infantry, was first to enter the blockhouse and take possession of the Spanish flag while members of the Twelfth entered on the other end and took possession of a white flag that was waived by the panicked Spaniards. Each group believed it was the first to capture the position. The Twenty-fifth Infantry sustained eight soldiers killed and 27 wounded at El Caney.

With the Spanish routed from El Caney, the focus shifted to the San Juan Heights. On the morning of July 1, 1898, the Tenth Cavalry along with the Ninth Cavalry and Twenty-fourth Infantry took up their positions around San Juan Heights. The Tenth Cavalry and Ninth Cavalry along with the First Cavalry and the First Volunteer Cavalry—the Rough Riders—held the far right of the American line that hot, humid morning. Their position was in tall grass along the San Juan River.

The Spanish troops were entrenched on San Juan Hill and Kettle Hill firing down on the Tenth’s position. The Spanish had found the range of the cavalry, and their rifle fire began to take a serious toll. Buffalo Soldier Edward L. Baker later wrote in his journal about this time, recounting, “the atmosphere seemed perfectly alive with flying missiles from bursting shells overhead, and rifle bullets, which seemed to have an explosive effect.”

Walking up and down the line of the Tenth’s position talking to the troops, Baker reassured them while bullets whizzed by. As Baker made his rounds, he heard a groan and saw Private Lewis Marshall of C Troop wounded and struggling face down in the San Juan River. Baker ignored the advice of other soldiers who told him it was too dangerous to try to save Marshall. Baker pulled Marshall from the water and carried him to safety. After carrying Marshall to safety, Baker alerted the regimental doctor to attend to Marshall’s wounds. Marshall survived, thanks to Baker’s actions. Baker received the Medal of Honor for these actions three years later in 1902.

Baker joined the rest of the Buffalo Soldiers in their fight up the San Juan Heights. During the battle, Baker was wounded by shrapnel in his left side and left arm. He continued picking his way through barbed wire entanglements on his way to the summit. He later wrote that the troopers “advanced rapidly…under a galling, converging fire from the enemy’s artillery and infantry.” Finally, Baker and the remaining members of the Tenth U.S. Cavalry along with the Rough Riders reached the summit and forced the Spaniards to retreat. A total of 26 Buffalo Soldiers died in the fight for San Juan Heights.

After the Battle of San Juan Heights, Rough Rider Frank Knox said, “I never saw braver men anywhere.” Lieutenant John J. Pershing wrote, “They fought their way into the hearts of the American people.”

Theodore Roosevelt commented, “… no one can tell whether it was the Rough Riders or the men of the 9th who came forward with the greater courage to offer their lives in the service of their country.” Despite this initial praise, Roosevelt later took a negative tack about the Buffalo Soldiers’ contribution to the victory: “Negro troops were shirkers in their duties and would only go as far as they were led by white officers.”

In response to Roosevelt’s revisionist statement, Tenth Cavalry Trooper Presley Holliday wrote in response, “His [Roosevelt’s] statement was uncalled for and uncharitable, and considering the moral and physical effect the advance of the 10th Cavalry had in weakening the forces opposed to the Colonel’s regiment, both at Las Guasima and San Juan Hill, altogether ungrateful and has done us an immeasurable lot of harm…not every troop or company of colored soldiers who took part in the assaults was led or urged forward by a white officer.”

After the Battle of San Juan Heights, the American forces were able to surround the capital and force the surrender of the Spanish on August 13, 1898. The war officially ended with the signing of the Treaty of Paris on December 10, 1898. The United States then took control of the former Spanish colonies of Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines. Cuba was given its independence from colonial rule at the end of the war.

To learn more about the Buffalo Soldiers during the Spanish- American War click here