Last updated: December 14, 2020

Article

“Determined to Make His Way to Mexico”: Freedom Seekers in the Antebellum Texas–Mexico Borderlands

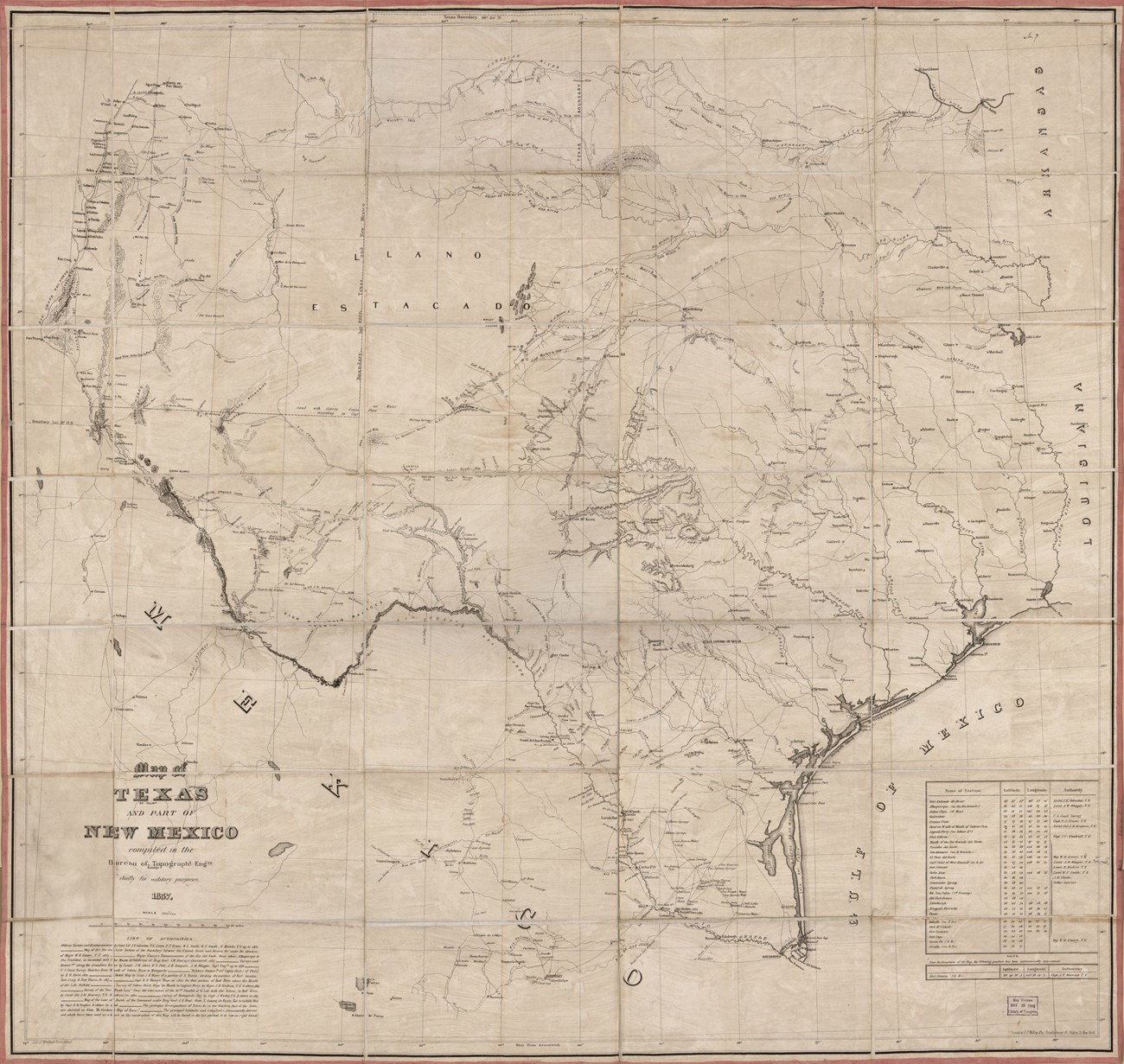

Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Each June Black communities across the United States celebrate Juneteenth, a day that commemorates African American freedom. The conclusion of the U.S. Civil War in April 1865 freed almost all enslaved people in the U.S. South, but Black men, women, and children in Texas remained in bondage until Union soldiers freed them in June 1865. However, not all enslaved Black people in Texas waited for the Union Army to liberate them. Some escaped south to Mexico in search of freedom decades before the Civil War began.

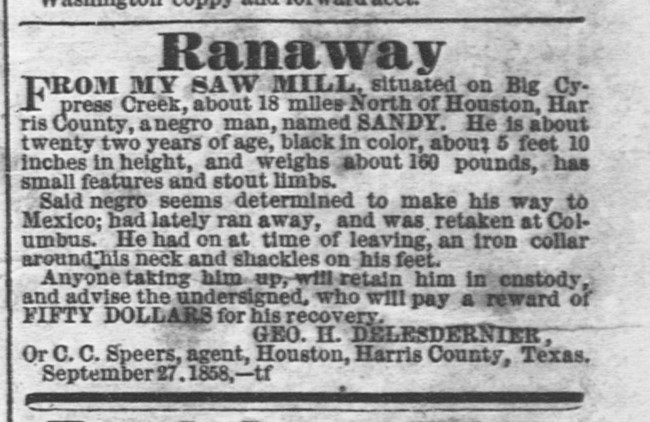

Courtesy of University of North Texas Libraries, The Portal to Texas History.

In September 1858 twenty-two-year-old Sandy escaped from Big Cypress Creek, Texas, which was eighteen miles north of Houston. This instance was not the first time that he had run away. The last time he had fled, someone captured him approximately 180 miles southwest of Big Cypress Creek.[1] Undeterred by this failed escape, Sandy was “determined to make his way to Mexico.”[2] Despite wearing an “iron collar around his neck and shackles on his feet,” Sandy ran away again hoping to find freedom.[3] There were limited opportunities for fugitives from slavery to receive aid during their escapes through Texas. If Sandy ventured near an enslaved community, he could obtain food from its members. If he arrived to Hidalgo County, Texas, he could seek refuge at Nathaniel Jackson’s ranch or use John Webber’s ferry to cross the Rio Grande.[4] While it is unknown if Sandy ever reached freedom in Mexico, his efforts show that enslaved Texans viewed the nation as a safe haven.

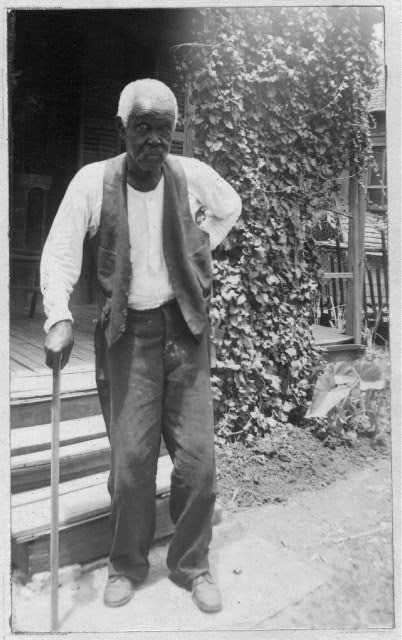

Federal Writer's Project, United States Work Projects Administration (USWPA)

Courtesy of Library of Congress

By the early 1850s most enslaved people in Texas knew that Mexico was their best option for freedom. In a 1937 Works Progress Administration interview, then ninety-two-year-old Felix Haywood recalled, “Sometimes someone would come ‘long and try to get us to run up North and be free. We used to laugh at that. There wasn’t no reason to run up North. All we had to do was to walk, but walk South. And we’d be free as soon as we crossed the Rio Grande.”[5] Haywood and others in his enslaved Texas community likely learned about freedom in Mexico from local Mexicans in Texas, or Tejanos. Because of this spread of information, enslaved people in Texas knew that the northern United States and Canada were not feasible places for freedom not only because of the significant distance, but also because Mexico had abolished slavery decades earlier. In 1829 Mexican President Vicente Guerrero abolished slavery, but he exempted Texas from abolition to placate Anglo enslavers. In 1837 Mexico abolished slavery again without any exceptions.[6] Men and women in bondage who thought about escape used their knowledge of abolition in Mexico and a limited understanding of their local areas to seek freedom in a northeastern Mexican state.[7]

Unlike enslaved Black people who escaped to the northern United States and Canada, there were few communities of antislavery activists to assist self-liberated Black people who arrived in Mexico. After crossing the Rio Grande, freedom seekers typically sought refuge in the nearest border town. Coahuila border town Piedras Negras was an important site of freedom in the U.S.–Mexico borderlands because fugitives from slavery frequently escaped there in the early 1850s; a nearby settlement of Mascogos (Black Seminoles from the United States) helped reinforce the idea of Coahuila as a space of refuge.[8] Still, self-emancipated Black people residing in Mexican border towns had to remain vigilant to maintain their freedom. Alarmed by the flight of enslaved people to Mexico, Anglo Texas enslavers employed Texas Rangers––Texas’s police force founded in 1835––to track, capture, and extradite freedom seekers who had reached Mexico. While the U.S. government could not enforce the Fugitive Slave Act (1850) outside of U.S. borders, Rangers and others employed to kidnap fugitives from slavery used violence to capture freedom seekers in Mexico and return them to Texas.

Enslaved people in Texas imagined their journeys to freedom differently than those in bondage in the Upper and Lower U.S. South. Drawing from information they gathered from local Mexicans and their own failed escape attempts, enslaved Texans crafted routes that guided them south to Mexico. Their experiences cast a new light on enslavement and resistance in antebellum Texas. While Juneteenth celebrates Black freedom gained shortly after the U.S. Civil War, there were many freedom seekers from Texas who self-emancipated to Mexico before 1865.

Article contributed by Mekala Audain - Associate Professor of History at The College of New Jersey.

Further Reading

Audain, Mekala. “Design His Course to Mexico: The Fugitive Slave Experience in the Texas–Mexico Borderlands, 1850–1853.” In Fugitive Slaves and Spaces of Freedom in North America, 1775–1860, edited by Damian Alan Pargas, 232–250. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2018.

Baumgartner, Alice L. South to Freedom: Runaway Slaves to Mexico and the Road to the Civil War. New York: Basic Books, 2020.

Cornell, Sarah E. “Citizens of Nowhere: Fugitive Slaves and African Americans in Mexico, 1833–1857.” Journal of American History 100. 2 (2013): 351–374.

Kelley, Sean. “‘Mexico in His Head’: Slavery and the Texas–Mexico Border, 1810–1860.” Journal of Social History 37. 3 (2004): 709–723.

Mareite, Thomas. “Conditional Freedom: Free Soil and Fugitive Slaves from the US South to Mexico’s Northeast, 1803–1861.” PhD diss. Leiden University, 2020.Nichols, James David. The Limits of Liberty: Mobility and the Making of the Eastern U.S.–Mexico Border. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2018.

Footnotes

[1] “Runaway,” The Weekly Telegraph (Houston, TX), October 20, 1858, University of North Texas Libraries, The Portal to Texas History, https://texashistory.unt.edu; crediting The Dolph Briscoe Center for American History.

[2]“Runaway.”

[3] “Runaway.”

[4] Roseann Bacha-Garza, “Race and Ethnicity along the Antebellum Rio Grande: Emancipated Slaves and Mixed Race Colonies,” in The Civil War on the Rio Grande, 1846–1876, eds. Roseann Bacha-Garza, Christopher L. Miller, and Russell K. Skowronek (College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2019), 94–95.

[5] George P. Rawick, ed., The American Slave – Texas Narratives, Vol. 4, Part 1 (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1972), 132. Emphasis in the original.

[6] Randolph B. Campbell, An Empire for Slavery: The Peculiar Institution in Texas, 1821–1865 (Baton Rouge: LSU Press, 1989), 25–26; Manuel Dublán y José Maria Lozano, Legislación Mexicana, o, colección complete de las disposiciones legislativas expedidas desde la independencia de la republica, tomo III (Mexico: Dublán y Lozano, 1876), 352.

[7] Campbell, An Empire for Slavery, 56.

[8] Frederick Law Olmstead, A Journey Through Texas; or a Saddle-trip on the Southwestern Frontier: With a Statistical Appendix (New York: Dix, Edwards & Co., 1857), 324. For more about Mascogos in Coahuila, see Kevin Mulroy, Freedom on the Border: The Seminole Maroons in Florida, the Indian Territory, Coahuila, and Texas (Lubbock: Texas Tech University Press, 1993).