Last updated: March 8, 2025

Article

Finding Places Buffered from Climate Change in a Bid to Protect Them

Existing tools to find and protect areas where the climate is changing more slowly may help us preserve resources into an uncertain future

By Cathleen Balantic

Image credit: NPS

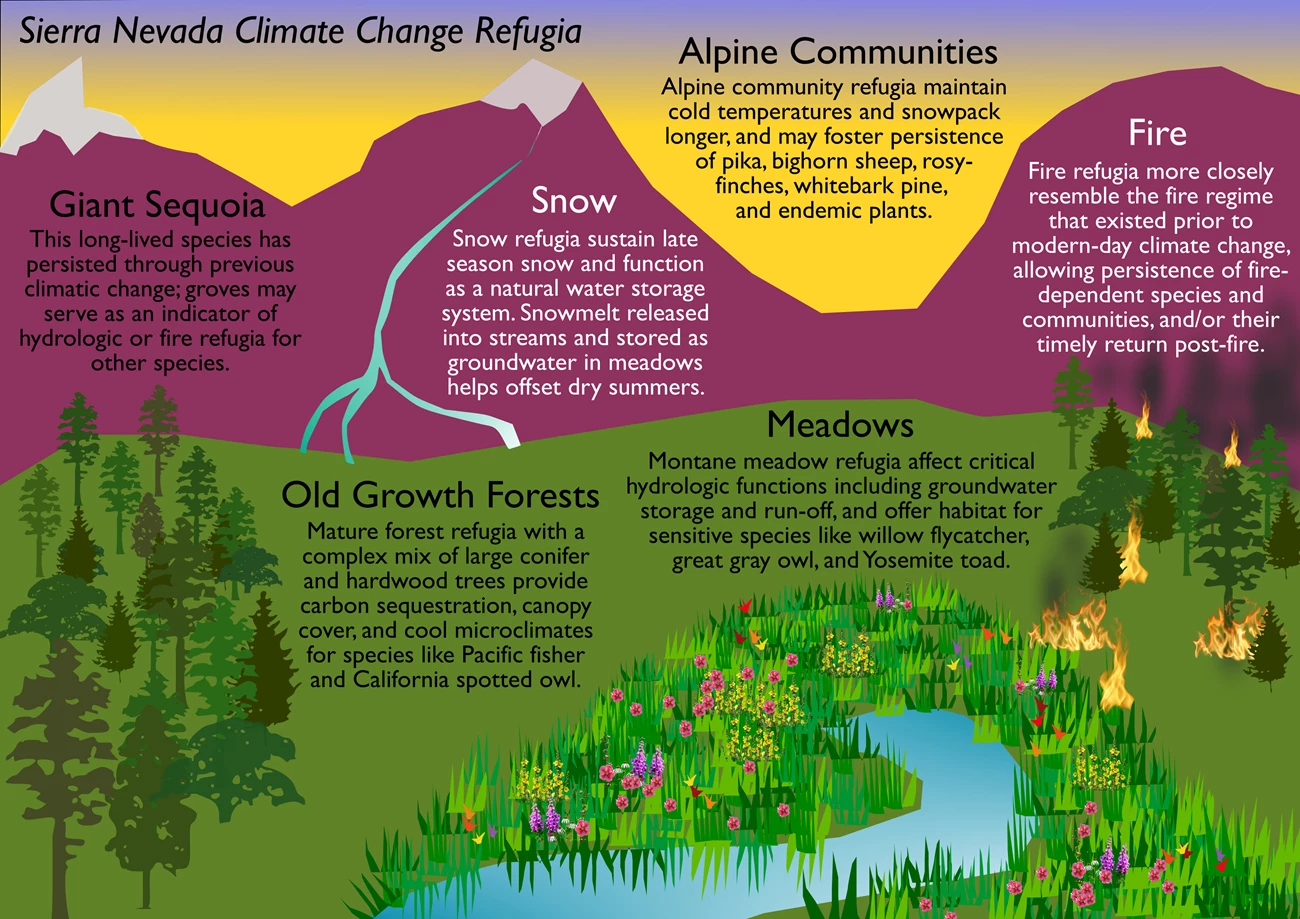

Climate change threatens entire landscapes across the western United States. Meadows, forests, and iconic species like the giant sequoia face pressure from intensifying wildfires and snow drought. Scientists and land managers are looking for practical solutions to cope with these enormous challenges. One solution is to protect climate change “refugia.” These are areas that experience more gradual effects from climate change than other places. Conserving refugia could allow precious resources to survive, but understanding how to identify and protect them can be difficult. A recent paper published in Conservation Science and Practice shows how we can use existing research and tools to find and preserve climate change refugia on a large scale.

Researchers from several institutions, including the National Park Service, conducted the study described in the paper. They analyzed examples of potential refugia in the Sierra Nevada mountains of California to illustrate how to identify and manage them. “Climate change refugia are places buffered from climate change that enable persistence of the things we care about,” said Toni Lyn Morelli, an ecologist with the U.S. Geological Survey and a coauthor on the paper. “The Sierra Nevada is highly exposed to climate change,” she explained, “so it feels extra important to find the places more buffered from climate change and protect them.”

The Sierra Nevada ecoregion is a prime area to consider for refugia conservation. It contains the highest mountain peak in the Lower 48, the largest alpine lake in North America, and a spectacular array of habitats, animals, and plants. Millions of people rely on its reservoirs for drinking water. Over 60 percent of the region is public land. Morelli thinks that so much of the Sierra Nevada is protected, land management agencies could collaborate on responses to climate change.

The urgency of climate change is acutely visible in the Sierra Nevada. The region recently experienced its most extreme drought in over a thousand years and the largest wildfires it has ever recorded. Experts predict that the end of this century will bring increasing challenges, making climate adaptation planning even more critical.

“This was a way for us to get a lot of experts together in the room to brainstorm and refine ideas that will help us in developing our climate adaptation strategies."

The study and paper were catalyzed by a workshop held at Yosemite National Park in 2019. The workshop included representatives from the National Park Service, U.S Geological Survey, and U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Forest Service, among others. Since then, Morelli and her colleagues at the Refugia Research Coalition have run several such climate change refugia workshops.

Nicole Athearn is the division lead for resource management and science at Yosemite National Park and a coauthor on the paper. She helped put on the first workshop. “This was a way for us to get a lot of experts together in the room to brainstorm and refine ideas that will help us in developing our climate adaptation strategies,” she said.

Rachel Mazur, a coauthor and program manager for the National Park Service North Cascades Inventory and Monitoring Network, said the primary purpose of the study was “to make the intangible tangible. There’s been a lot of talk about refugia, which is an important first step, but how does that talk translate to action on the ground?”

To start answering that question, the authors looked at different natural resources in the Sierra Nevada. They divided refugia examples into two kinds of resources: “process-based” (snow and fire) and “ecosystem-based” (meadows, old-growth forests, alpine communities, and giant sequoia). They analyzed those resources using the Climate Change Refugia Conservation Cycle that Morelli and her colleagues had previously described.

Image credit: Society for Conservation Biology

By mapping areas with fewer expected temperature and precipitation changes, scientists can find potential climate change refugia. Managers may choose to perform tricky and costly management actions in those areas, such as restoring stream flow in refuge meadows. Once a refuge is identified, protecting it from non-climate stressors like heavy visitor use could allow it to persist despite climate change. Managers could also choose not to restore or protect an area, because the future climate may not support the resources at that location.

Morelli said the study “not only brings all that information together but also has the group thinking about taking action for climate adaptation for those resources.” For example, the study helped spark a new conservation project for the foothill yellow-legged frog in the Sierra Nevada. Morelli said that project aims to create “refugia maps that will help prioritize where to do conservation actions like restoration, translocation, and bullfrog removal."

There are other examples of how people are using this work. Athearn said the Yosemite Conservancy has funded a project to develop a science strategy for Yosemite National Park that includes climate change refugia. She said the Yosemite refugia project will help inform the climate adaptation component of their strategy.

“This is about exercising options in strategic ways. We’re doing what we can, and we’re having to be honest about our capabilities in a changing world.”

Gregor Schuurman, an ecologist with the National Park Service Climate Change Response Program, agreed that “understanding refugia and having them be part of our approach is important. These are low-hanging fruit for conserving historical or natural conditions.” But protecting climate change refugia may not be a long-term solution. Schuurman cautioned that the approach doesn’t guarantee parks can protect treasured resources. “This is about exercising options in strategic ways. We’re doing what we can,” he said, “and we’re having to be honest about our capabilities in a changing world.”

Mazur concurred. “We’re moving forward with the goals of protecting rare species, habitats, and processes in a rapidly changing time,” she said. “Considering the role of refugia can be key to effectively prioritizing areas to protect and restore, but it is just one piece of a very complex picture.”

About the author

Cathleen Balantic is a biologist with the National Park Service's Natural Sounds and Night Skies Division. She specializes in bioacoustics. She works on projects that use biological sounds to learn about wildlife in our national parks. Image credit: NPS / Cathleen Balantic