Part of a series of articles titled People of the Mormon Pioneer Trail.

Article

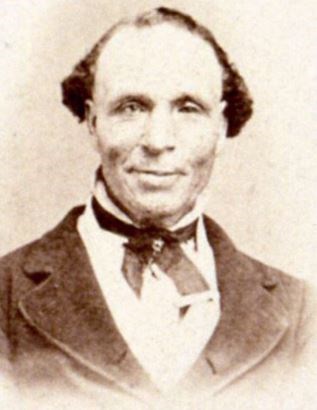

Elijah Abel, the Mormon Pioneer Trail

Photo/ Public Domain, Wikimedia Commons

Elijah Abel – Mormon Pioneer Trail[1]

By Angela Reiniche

(Special thanks to Chad M. Orton and Jessica M. Nelson)

Elijah Abel (also spelled Able or Ables) was born in Maryland in 1810, possibly into slavery.[2] An early convert to Mormonism (officially, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, or LDS Church) and one of the faith’s first Black members, Abel gathered with other Latter-day Saints in Kirtland, Ohio, soon after his 1832 baptism. Four years later, in 1836, Ambrose Palmer—a presiding Elder in Ohio—ordained Abel. Later that year, in December, Abel was ordained a Seventy (a member of an important council of Church leaders) by Zebedee Coltrin; this distinction gave him limited authority to organize and proselytize on behalf of the Latter-day Saints, with the primary duty of administering and spreading the LDS faith. Also in 1836, at the direction of LDS Church founder Joseph Smith, Jr., Abel received his ritual washings and anointings in the Kirtland Temple. He also received a blessing from Joseph Smith, Sr., the patriarch of the church. Abel’s patriarchal blessing was different from those received by his fellow white Saints. Smith pronounced him an “orphan,” promising that “thou shalt be made equal to thy brethren, and thy soul be white in eternity and thy robes glittering.”[3] Abel’s blessing showed that, while Black people could claim some space in early Mormonism, they were also subject to a racial “othering” that differentiated them other church members.”[4]

In the earliest years of his missionary service, Abel labored in New York and Canada, where his activities generated enough controversy among non-Mormons and his fellow missionaries that church leaders took notice. Non-Mormon residents of St. Lawrence County accused Abel of murdering a woman and five children, but he successfully fought the charge. After that, his fellow missionaries in Canada complained about the content of his teachings and claimed that Abel had threatened to assault a fellow missionary. (He admitted to the latter, but with the rejoinder that “knocking around with Brothers” was commonplace.)[5] Church leaders chose not to take any disciplinary action against him.

In 1839 Abel left Canada for Nauvoo, Illinois, where Joseph Smith, Jr. and about ten thousand of his followers had relocated after their expulsion from the state of Missouri.[6] Abel spent three years there living on property he purchased from Smith. [7] During that time he employed his carpentry skills, even serving as an undertaker in what had become one of the state’s most populous cities. In 1842, for reasons that remain unclear, Abel moved to Cincinnati, Ohio, where he helped serve the local LDS community as a church leader. While in Cincinnati, Abel met and married Mary Ann Adams, a Black woman who had been born in Tennessee in 1829—making her approximately twenty years younger than her new husband.[8]

Abel had grown close to the Smith family while in Nauvoo, and his activities in New York and Canada added to his notoriety.[9] His visibility as a Black ordained elder, however, created some consternation among other church leaders. In 1843, during a regional conference in Cincinnati, apostles John E. Page, Orson Pratt, and Heber Kimball presided over a discussion of Abel’s standing in the church. Page argued that, while he respected Abel, “wisdom forbid that we should introduce [him] before the public.” In other words, given the nation’s deep divisions over issues of race and slavery, Page thought it unwise for the Latter-day Saints to appear racially progressive.[10] Pratt and Kimball echoed Page’s concerns and the trio drafted a resolution to restrict Abel’s duties, confining him to local work and instructing him to work only with Cincinnati’s Black population. The conference marked the first documented placement of racially-based restrictions upon a priesthood officeholder.[11]

Following the death of Joseph Smith at Carthage, Illinois, in 1844, Latter-day Saints moved to the Great Basin—where Abel found further changes for him as a Black member of the church. The exact reasons for these changes are not entirely known. One factor, however, appears to be the tensions that arose from the confluence of U.S. territorial expansion and the nation’s mounting sectional crisis that led to the Compromise of 1850 and legalization of slavery in the newly-formed Territory of Utah. In 1852 Brigham Young, Joseph Smith’s successor and Utah Territory’s first governor, addressed Utah’s newfound status as a slave territory by telling the territorial legislature that men of Black descent were not eligible for the priesthood. Consequently, neither Black men nor women would be allowed to participate in the temple endowment or sealing ordinances.[12]

The following year Elijah and Mary Ann migrated to Salt Lake City along with their children Moroni, Enoch, and Anna. That same year, Abel petitioned Young to receive the temple endowment and be sealed to his wife and children. While Young officially kept Abel’s priesthood status intact, he denied the petition—marking perhaps the first documented instance of a person of color being denied this particular privilege. More broadly, this refusal was one of the first times that a person of color was denied participation in practices central to the Mormon faith.[13]

After Young’s death in 1877, Abel again petitioned to be allowed to participate in the temple endowment and sealing ordinances. Once again, however, the church refused him. Despite being denied full access to the rights and privileges of the priesthood, Abel remained devout and soldiered on with his missionary activities. He served three more missions, making his last trip to the eastern states in 1883, the year before his death.[14] Abel died on 25 December 1884, due to “exposure while laboring in the ministry in Ohio.”[15]

When Young made his declaration in 1852 regarding Blacks and the priesthood, he also declared that at some future date Black church members would “have the privilege of all we have the privilege of and more.”[16] In 1978, almost a century after Elijah’s death, the LDS Church re-opened the priesthood to men of African descent. More than twenty years later, in September 2002, the church sent apostle M. Russell Ballard to dedicate a monument that had been erected in Salt Lake City to honor Elijah and Mary Ann Abel’s “[contributions] to the early growth of the state and to their chosen faith.”[17]

[1] Part of a 2016–2018 collaborative project of the National Trails – National Park service and the University of New Mexico’s Department of History, “Student Experience in National Trails Historic Research: Vignettes Project” [Colorado Plateau Cooperative Ecosystem Studies Unit (CPCESU), Task Agreement P16AC00957]. This project was formulated to provide trail partners and the general public with useful biographies of less-studied trail figures—particularly African Americans, Hispanics, American Indians, women, and children.

[2] For a brief overview of Abel’s life, see W. Paul Reeve, “Able, Elijah,” Century of Black Mormons, University of Utah Libraries, accessed 18 July 2022, https://exhibits.lib.utah.edu/s/century-of-black-mormons/page/able-elijah - ?c=&m=&s=&cv=&xywh=-62%2C139%2C1656%2C845.

[3] “Joseph Smith's Patriarchal Blessing Record,” 88, recorded by W. A. Cowdery. Original, LDS Church Archives, quoted in Newell G. Bringhurst, “Elijah Abel and the Changing Status of Blacks within Mormonism,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 12, no. 2 (Summer 1979), 24.

[4] Joseph R. Stuart, “‘A More Powerful Effect upon the Body’: Early Mormonism’s Theory of Racial Redemption and American Religious Theories of Race,” Church History 87, no. 3 (Sept. 2018): 776.

[5] Bringhurst, “Elijah Abel,” 24. Bringhurst mentions an incident in St. Lawrence County, New York, during which non-Latter-day Saint residents accused Abel of murdering a woman and five children and had offered a monetary reward for his capture. He successfully refuted the charges. Bringhurst also draws from an 1839 meeting of the Quorum of the Seventy that discussed accusations that he had behaved violently in New York and complaints from his fellow missionaries that his teachings had not been in keeping with Mormon doctrine, found in “Minutes of the Seventies Journal,” 1 June 1839. See also Newell G. Bringhurst, Saints, Slaves, and Blacks: The Changing Place of Black People within Mormonism (Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1981), 149.

[6] The Mormon migration from Missouri to Illinois took place in the wake of the 1838 Missouri Mormon War and after the Missouri governor, Lilburn Boggs, issued Missouri Executive Order 44, commonly known as the “Extermination Order” among Church members. EO 44 stated that Mormons be treated as enemies to be either “exterminated or driven from the State if necessary for the public peace.” The order remained in place until 1976. See Stephen C. LeSueur, The 1838 Mormon War in Missouri (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1990).

[7] For documentation of Smith selling property to Abel, see “Bond to Elijah Able, 8 December 1839,” Joseph Smith Papers, accessed 18 July 2022, https://www.josephsmithpapers.org/paper-summary/bond-to-elijah-able-8-december-1839/1.

[8] The marriage took place on 16 February 1847 in Hamilton County, Ohio. Ohio, County Marriage Records, 1774–1993 [database on-line] (Lehi, Utah: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2016). Original data: Marriage Records. Ohio Marriages. Various Ohio County Courthouses.

[9] On the relationship between Smith and Abel, see Kate B. Carter, The Story of the Negro Pioneer (Salt Lake City: Utah: Daughters of Utah Pioneers, 1965); and Andrew Jenson, “Elijah Abel: The Only Negro Who Is Known to Have Been Ordained to the Priesthood,” Latter-Day Saint Biographical Encyclopedia, vol. 3 (Salt Lake City, Utah: Deseret News Press, 1920), 577.

[10] Years earlier when the church tried to establish headquarters in Missouri, tensions arose between the Latter-day Saints, who were viewed as social radicals seeking to bring "free Negroes & Mulattoes from other States to become Mormons,” and their slave-holding neighbors. Letter from John Whitmer, 29 July 1833, Joseph Smith Papers, accessed 18 July 2022, http://josephsmithpapers.org /paperSummary/letter-from-john-whitmer-and-william-w-phelps-29-july -1833.

[11] Page quoted in Chester L. Hawkins, “Report on Elijah Abel and His Priesthood,” 4 December 1985, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah; W. Kesler Jackson, Elijah Abel: The Life and Times of a Black Priesthood Holder (Springville, Utah: Cedar Fort, Inc., 2013); and Newell G. Bringhurst, “Chapter 4: Elijah Abel and the Changing Status of Blacks within Mormonism,” in Lester E. Bush and Armand L. Mauss, Neither White Nor Black: Mormon Scholars Confront the Race Issue in a Universal Church (Midvale, Utah: Signature Books, 1984).

[12] Brigham Young, “Speech in Joint Session of the Legislature” (speech, Salt Lake City, Utah, 5 January 1852), Utah Lighthouse Ministry, accessed 18 July 2022, http://www.utlm.org/onlineresources/sermons_talks_interviews/brigham1852feb5_priesthoodandblacks.htm.

[13] For more on William McCary, another person of color who pushed the church’s boundaries of racial acceptance, see Russell M. Stevenson, “‘A Negro Preacher’: The Worlds of Elijah Ables,” Journal of Mormon History 39, no. 2 (Spring 2013): 228–33.

[14] Susan Easton Black, compiler, Membership of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1830–1848, 50 vols. (Provo, Utah: Brigham Young University Religious Studies Center, 1989), Private Donor; Moore, Sweet Freedom’s Plains, 32–33; Nauvoo Neighbor, 10 September 1845, and Latter Day Saints Millennial Star (published in Liverpool, England), September 1843, both quoted in Bringhurst, “The Mormons and Slavery,” 332; Bringhurst, Saints, Slaves, and Blacks, 37–39; Newell Bringhurst, “‘The Missouri Thesis’ Revisited: Early Mormonism, Slavery, and the Status of Black People,” in Black and Mormon, ed. Newell G. Bringhurst and Darron T. Smith (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2006), 13–33; and Margaret Blair Young, “Abel, Elijah (1810–1884),” Black Past, accessed 18 June 2017, http://www.blackpast.org/?q=aaw/abel-elijah-1810-1884.

[15] Obituary of Elijah Able, Desert News, 31 December 1884.

[16] Young, “Speech in Joint Session of the Legislature,” 1852.

[17] “New Monument Erected to Honor Elijah Abel Family,” Deseret (Utah) News, 25 September 2002, available online at https://www.deseretnews.com/article/939027/New-monument-erected-to-honor-Elijah-Abel-family.html, accessed 18 June 2017; and Salt Lake County, Utah, Death Records, 1908–1949 [database on-line] (Provo, Utah: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2014).

Last updated: March 6, 2023