Last updated: November 22, 2021

Article

Cuyahoga Valley's Ties to the Underground Railroad

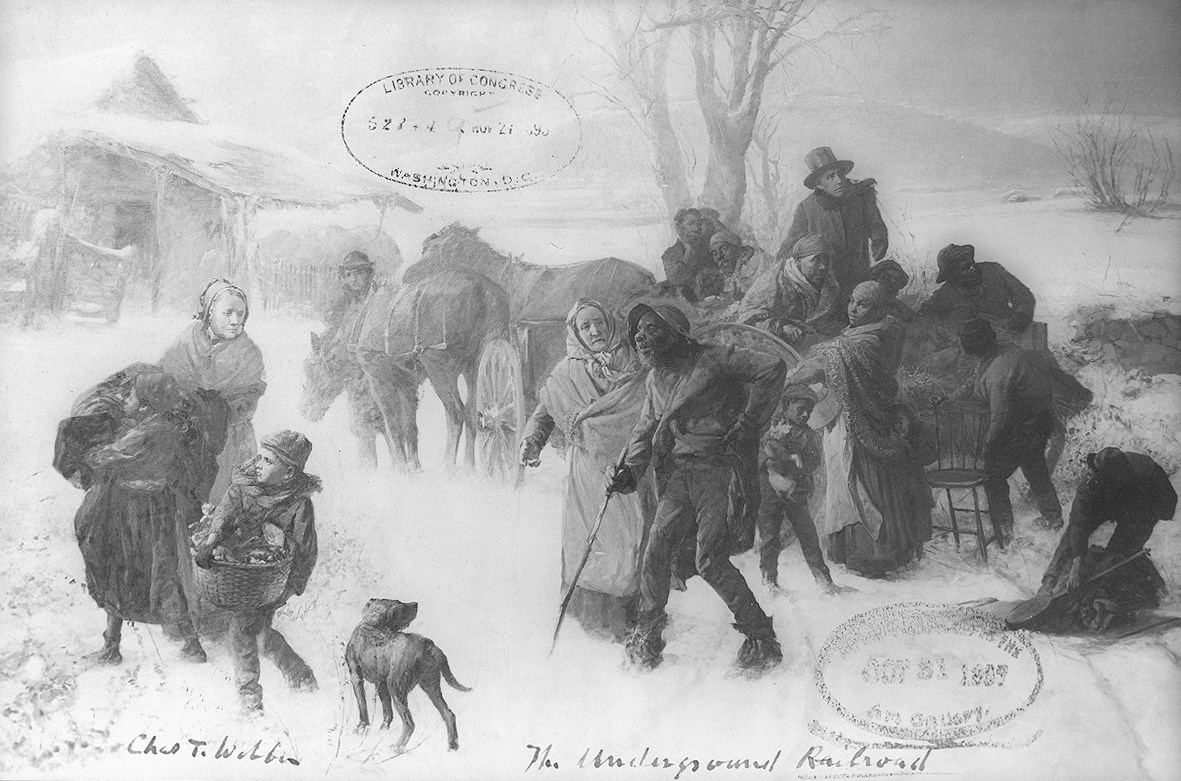

Courtesy Library of Congress

From the birth of our nation until the Civil War, the Underground Railroad transported people of color from slavery toward freedom. Not an actual train, the Underground Railroad was a system of secret routes fanning away in all directions from slave states. It involved many courageous individuals: each enslaved person who tried to escape or who offered food and direction, freedom seekers who returned south to help others flee, and free Blacks and Whites who provided assistance. Cuyahoga Valley National Park interprets Ohio’s Underground Railroad heritage because a centerpiece of our park, the Ohio & Erie Canal, was a likely route.

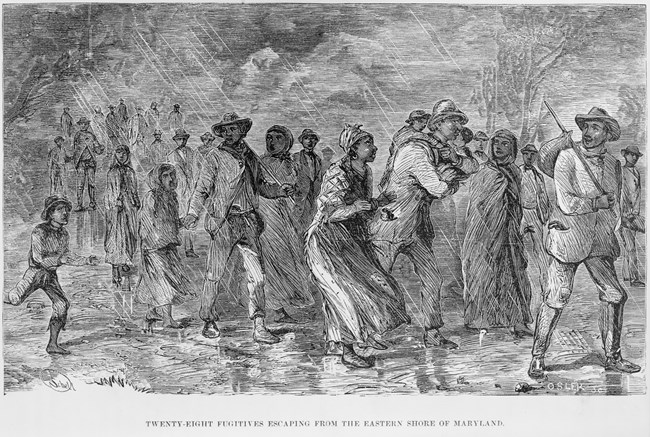

Courtesy Library of Congress

Trail to Freedom

Who do you love most in this world? Could you leave them behind and travel an Underground Railroad toward freedom? The decision to flee was not made lightly. It often meant leaving behind cherished family and friends who might be punished for your actions. Still, some chose flight. Freedom seekers journeyed by any means possible—by foot, wagon, railroad, and canal. Letters and oral histories conducted by historian William Siebert in the 1880s indicate that Ohio’s canals were used to transport cargo, a common code word for enslaved people.

The Ohio & Erie Canal clearly presented advantages to anyone trying to cross Ohio. This 308-mile canal was a well-marked route connecting the Ohio River to Lake Erie. Some freedom seekers might have walked or run under cover of night along the canal’s towpath—north to Cleveland. Others might have reached Cleveland hidden aboard canal boats with assistance from a friend of a friend, a common code for sympathetic people along the way. From Cleveland, or Hope, they would take the final step to freedom by crossing Lake Erie into Canada. The only documented account that we've found to date is the account of Lewis G. Clarke who gained his freedom by purchasing a boat ticket to travel from Portsmouth to Cleveland.

Law of the Land

Written into the Constitution of the United States, “involuntary servitude” permitted people to own other people. Subsequent laws made it illegal to assist "runaways" and stipulated where slavery could exist. The second Fugitive Slave Act passed in 1850 stated that anyone assisting a freedom seeker would be fined $1,000 and spend six months in a federal prison. It also required law enforcement officers to assist slave catchers and allowed them to search homes.

A Hotbed of Abolitionists

Despite the dangers, people known as abolitionists believed that slavery should not exist and fought to end it. Northeast Ohio was a hotbed of abolitionist activity. Men and women, Black and White, free and enslaved, worked together for their cause.

Many were entering the political arena for the first time. Women in Northeast Ohio organized female anti-slavery societies, circulated petitions, served as delegates to state and national antislavery conventions, and drafted editorials that were published in local papers such as The Anti-Slavery Bugle. In time, growing political experience and awareness of the plight of enslaved people, inspired women to consider their own freedom more critically; the women’s suffrage movement grew from the ranks of the abolitionist movement.

Free Blacks were a small but active abolitionist group in Northeast Ohio. They actively fought for the abolishment of Ohio’s Black Laws and segregation, and for the education of their children. Through organized meetings and petitions, they slowly changed state laws. John Malvin (1795-1880), a free Black abolitionist and canal boat captain, was considered by some to be the founder of the civil rights movement in Cleveland. When Malvin refused to be segregated in church, he set in motion a trend of activism. If Blacks and Whites could pray next to each other, they could also live side by side. Although he does not mention it in his autobiography, it is plausible that Malvin assisted freedom seekers escaping along the canal.

NPS / Ted Toth

Preserving the Stories

In 1998 Congress passed the National Underground Railroad Network to Freedom Act to ensure that stories of the resistance against slavery in the United States are shared and remembered. Abolitionism illustrates a founding principle of this nation: all human beings have the right to self-determination and freedom from oppression. The Network to Freedom, coordinated by the National Park Service, recognizes historic sites, facilities, and programs that have a verifiable association to the Underground Railroad.

The Struggle Continues

Did you know that as many as 27 million enslaved people live in the world today? And they are found in almost every country including the United States according to Kevin Bales, consultant to the United Nations on human slavery and trafficking. We hope that the courage of those who resisted slavery in past centuries inspires you to think more deeply about human rights and consider ways to create a more compassionate modern society. You have the power to write a letter, sign a petition, and shop responsibly. Learn more about human trafficking in Ohio from the Ohio Human Trafficking Task Force.