Last updated: May 6, 2021

Person

John Malvin

© Arrye Rosser

John Malvin was born in Prince William County, Virginia in 1795. He was the son of a slave and a free black woman. John Malvin was born free because children assumed the status of their mother. In 1802, John Malvin was bound to his father’s owner where he learned carpentry, and to read and write. After a previous attempt to escape failed, John Malvin left Virginia for Ohio in 1827. In 1831, he and his wife Harriet Dorsey settled in Cleveland. He had several professions throughout his life — including a carpenter, a cook, and a canal boat captain.

In His Own Words

John Malvin wrote an autobiography of his life as a free black man during the time of slavery. It covers 50 years, 47 of which were spent living in Cleveland. John Malvin cared deeply about civil rights, establishing the first schools for black children in Ohio and becoming a prominent advocate for the rights of African Americans. John Malvin’s autobiography was first published by the Cleveland Leader in 1879. These quotes help us understand how difficult life was for black people, even in a slavery-free state like Ohio.

Traveling to Cleveland by Canal

“My wife met me in Cincinnati, and then we started up the Ohio River as far as Portsmouth, Ohio, with what little household goods we had. My object was to reach Chillicothe, to which point the Ohio Canal had been completed, and then travel by way of the canal. I hired a team to take us and our goods to Chillicothe, and from there we traveled on the canal to Newark, in Licking county. By this time cold weather had set in, and we were compelled to spend the winter in Newark. In the following April, the canal being again open, we proceeded on our journey, and arrived in Cleveland the same month. There was very little communication between the United States and Canada in those days, so we waited in Cleveland for a good opportunity to cross over into Canada, and finding no opportunity in Cleveland we went to Buffalo [New York], where we stayed a few days…

Here [in Buffalo] my wife became greatly troubled in consequence of having left her father, and it lay so heavily upon her that she gave me no rest. Seeing her unwillingness to go to Canada, and her fears that she would never see her father again, I concluded to give up the farm, and my wife having taken a fancy to Cleveland, we determined to go back and settle there…I sought employment at my trade [carpentry]. But my color was an obstacle and I could not get work of that kind. I managed, however, to obtain employment as cook on the schooner Aurora, that sailed on the lakes between Mackinaw [Michigan] and Buffalo.”

Racism

“I thought upon coming to a free State like Ohio, that I would find every door thrown open to receive me, but from the treatment I received by the people generally, I found it little better than in Virginia…Thus I found every door closed against the colored man in a free State, excepting the jails and penitentiaries, the doors of which were thrown wide open to receive him. I was for some time uncertain whether to remain in Ohio, or to return to Virginia, but at length concluded to remain in Ohio for a time, not knowing what to do.”

Buying a Boat

“My earnings while in Mr. Hudson’s employ, were barely sufficient to support my family. Through the kindness of Mr. James S. Clark, I was enabled to purchase, on easy terms, a vessel owned by Abraham Wright of Rockport. When I went to take out a license, the deputy Collector refused to grant it, deciding that my color was an obstacle. But when the Collector himself arrived, who was the Hon. Samuel Starkweather, well known to all the citizens of Cleveland, he decided that I had as much right to own and sail a vessel upon the lakes as I had to own a horse and buggy and drive through the streets, and he granted me a license. My vessel was called “The Grampus.” After I obtained my license, Mr. Diodate Clark employed me to carry limestone and cedar posts from Kelley’s and surrounding islands [in Lake Erie].”

Canal Boat Captain

‘“[In 1840], [I] purchased a canal boat from S.R. Hutchinson & Co…My boat, which was called the “Auburn,” was engaged in conveying wheat and merchandise on the Ohio Canal. The boat was a good passenger packet, with good cabins, and her former owners concluded to buy the boat back, which they did. They then employed me as captain, to manage her. On one occasion…we arrived at Niles, [Ohio] about nine o’clock in the evening. At this place we were hailed by some person saying that a passenger wanted to get aboard to go south. We came alongside the dock and landed. Pretty soon after some baggage came on board, and in a short time the owner of the baggage, who was a female, appeared.

My crew consisted of one white steersman, one colored steersman, two white drivers, one colored bowsman, and one colored female cook. When the lady arrived I stood aboard of the stern deck and assisted her aboard. When she went down into the cabin and saw the colored cook, she was taken completely by surprise. The colored steersman just then happened to go down into the cabin after something. The lady was sitting on the locker, and when she saw the colored steersman she went immediately to the other side of the boat. After the bowsman had got his line snugly curled, he went down into the cabin, and she accosted him, saying that she would like to see the captain. Accordingly, I was called and went down to see what she wanted. The light shone in my face so that she could easily see my features. The lady, after seeing me, suddenly sprang to her feet, and with great shortness of breath exclaimed, “Well, I never! Well, I never! Well, I never!” I made a bow and left her, and ordered the cook to set her state-room doors open, and take off all the bedding from the middle berth, and supply clean bedding from the locker, so that she might see that the bedding was changed, and I requested the cook to tell the surprised lady to take the middle berth. She refused to go to bed, and sat up all night.

We arrived at Lock 21, north end of Akron locks, at midnight. At nearly every lock there was a house or grocery, and I instructed the crew to keep the blinds on the boat closed, so that the lady should not know she was in a village; for, seeing that she was afraid of colored people, I wanted to giver her full opportunity of getting acquainted with them before she arrived at her home in Circleville. We arrived at Lock 1 a little after daylight…I invited the lady to breakfast, which she refused, saying that she did not feel very well...I [later] invited the lady to dinner. She still complained of not feeling very well, but took a piece of pie from where she stood. Then we arrived at the Bethlehem level, and when tea was ready, I invited her to tea, and she took a cup of tea and a biscuit.

[That night] I suppose the lady took a good night’s sleep, for I did not hear anything from her until the next morning. When breakfast was ready, on receiving an invitation, she readily took a seat at the table, and ate a hearty meal, and from that time on she felt reconciled to her surroundings, and conversed freely with the cook and all on board. When we arrived at Circleville she left us. I provided means for the conveyance of her baggage, and on her leaving she thanked me, and said, ‘Captain, when I first came aboard your boat, not being accustomed to travel in this way, I supposed I must have acted quite awkward. Now, I must return my thanks to you and your crew, for the kind treatment I have received. I never traveled so comfortably in all my life, and I expect to go north soon, and I will defer my journey until you are going north, even if I am obliged to wait two or three days.’ I never saw the lady again after that.”

Learn More

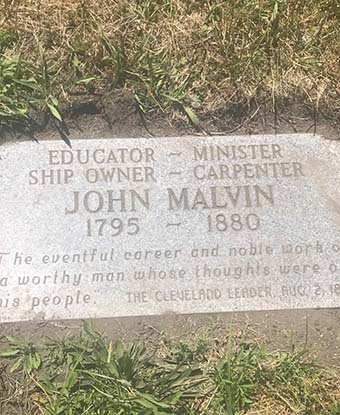

His grave in the Erie Street Cemetery is just north of the large dark "Barnet" monument. The inscription comes from his obituary: "The eventful career and noble work of a worthy man whose thoughts were of his people, John Malvin, an accomplished educator, ship owner, minister, and carpenter." Find out more about John Malvin and visit his historic marker.

Bibliography

Peskin, Allan, editor. North Into Freedom: The Autobiography of John Malvin, Free Negro, 1795-1880. Cleveland: The Western Reserve Historical Society, 1996.