Last updated: January 12, 2026

Article

Why a National Park? Highlights from the 1974 Hearings to Designate Cuyahoga Valley NRA

Akron-Summit County Public Library / John Seiberling Collection

Why was Cuyahoga Valley preserved as a national park? The arguments for and against were laid out during a series of three congressional hearings in 1974. Success was uncertain. The first attempt, a bill introduced in 1971, withered when Congress questioned the level of public support. The National Park Service and Department of the Interior opposed the idea. The pressures of suburban sprawl threatened the integrity of valley resources. In the face of this, park advocates rallied in support of the bill to make the proposed Cuyahoga Valley National Recreation Area (CVNRA) a reality.

Timeline of Events

- April 22, 1971 – Congressman John F. Seiberling (D-Ohio) introduces the “Ohio Canal and Cuyahoga Valley Recreation Development Act” (H.R. 7673). The bill fails to pass.

- April 16, 1973 – Congressman Seiberling introduces House Bill 7167 (7077) to create “Cuyahoga Valley National Historical Park and Recreation Area.”

- March 1, 1974 – The first House Subcommittee meeting on “H.R. 7167 and Related Bills” is held in Washington, DC. Public testimony begins.

- April 8, 1974 – The first Senate Subcommittee meeting on National Parks and Recreation is held in Peninsula, Ohio.

- June 7, 1974 – The House Subcommittee takes a whirlwind tour of Cuyahoga Valley and beyond. The field trip begins with a helicopter trip in the morning and a bus tour in the early afternoon. The day also includes a boat ride in Canal Fulton, an evening reception and tour at Stan Hywet Hall, and a cookout at Hale Farm & Village.

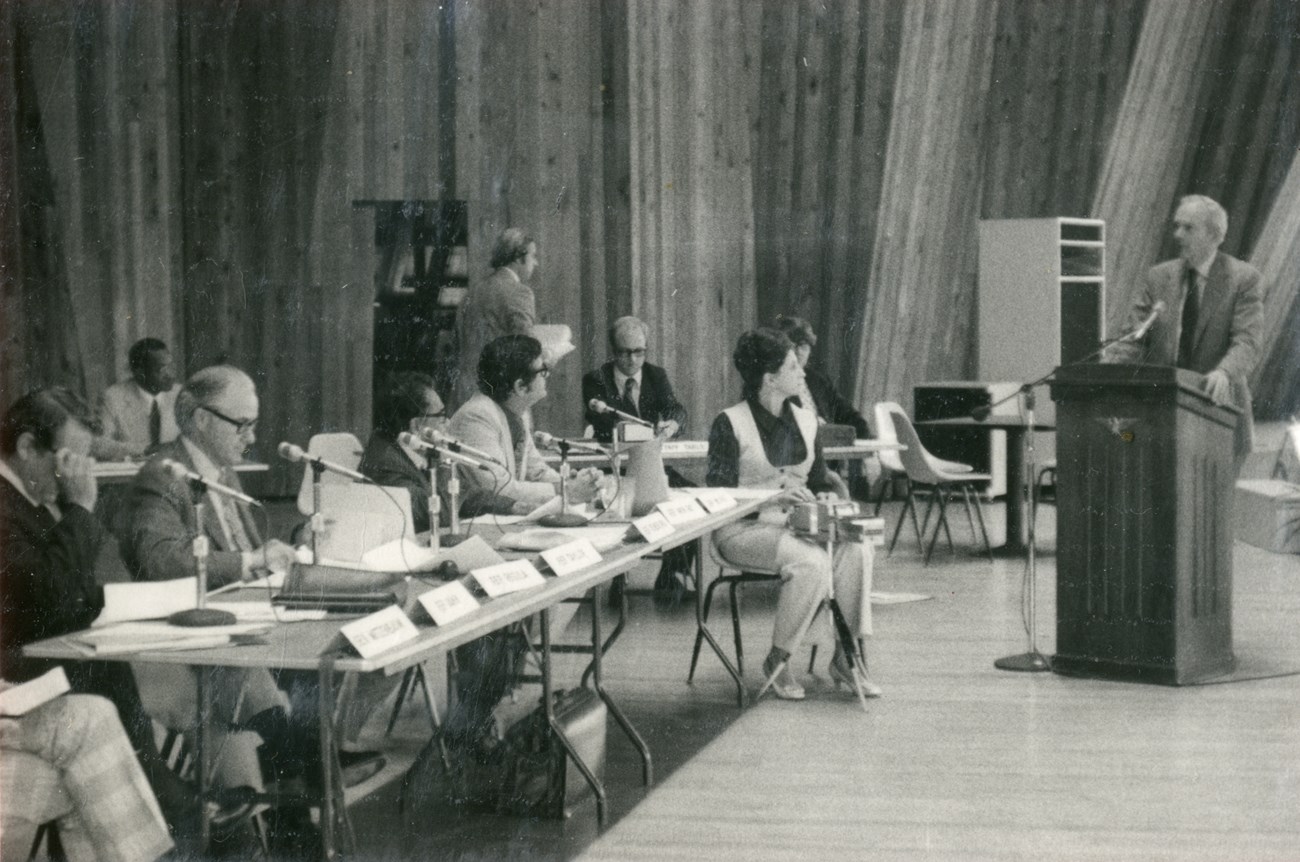

- June 8, 1974 – The House Subcommittee holds a full day of hearings at Blossom Music Center. In the evening, local architect and preservationist Bob Hunker hosts a reception and dinner at his home in Peninsula.

- September 30, 1974 – The House Subcommittee marks up the park bill. The name is changed to Cuyahoga Valley National Recreation Area.

- December 9, 1974 – The House passes the amended CVNRA bill, H.R. 7077.

- December 12, 1974 – The Senate passes H.R. 7077.

- December 24, 1974 – President Gerald R. Ford receives a briefing memo recommending that he veto the bill to create CVNRA.

- December 27, 1974 – US Senator Robert Taft, Jr. (R-Ohio) and Senator Howard Metzenbaum (D-Ohio) both call President Gerald Ford, who is on a ski vacation, to advocate for the park bill. The president signs Cuyahoga Valley National Recreation Area into being.

- June 26, 1975 – Secretary of the Interior Rogers Morton establishes Cuyahoga Valley National Recreation Area, now Cuyahoga Valley National Park.

Akron-Summit County Public Library / John Seiberling Collection

Now or Never

By 1974, it was literally now or never for the preservation of Cuyahoga Valley. No one knew this better than US Congressman John Seiberling (D-Ohio) who grew up nearby at the Stan Hywet estate in Akron. In his congressional testimony, Seiberling says, “It is a miracle that we can still talk about the Cuyahoga Valley as a proposed park and not as another commercial development. The Valley, stretching between the southern suburbs of Cleveland and the northern suburbs of Akron, is the last large expanse of open space remaining in this heavily industrialized area. With its magnificent cliffs and woods, waterfalls, and meadows, it is a pastoral wonder, a quiet haven away from the nearby bustling cities.”

In his statement, Ohio Governor John Gilligan expands on this by saying, “. . . the significance of the Cuyahoga Valley rests not only in the fact that it is a recreational and aesthetic oasis in the midst of a rapidly expanding supermetropolis; the Valley is important for its natural and cultural history as well.” He also notes, “In concluding that the Valley is of great national significance, a study conducted by the Park Service refers to the area as a ‘green shrouded miracle,’ and it underscores the urgency of designation of the area as a national park when it warns that ‘the urban noose is tightening’ and that this is the ‘region's last hope.’ The same study states unequivocally that ‘federal expertise and funding are essential.’”

Senator Howard Metzenbaum (D-Ohio) notes, “The State of Ohio has committed $125 million since 1965 to buying and developing parkland. State and regional authorities are buying valley land. But the financial reality is that the prices will run away from us if we do not do something on this subject and do it soon.”

Edward Fritz of the Northeast Ohio Group of the Sierra Club testifies, “Travel on any of the major highways between Cleveland and Akron . . . and it is apparent that the area is either developed or destined for development. The prominent feature of practically every vacant lot and open area are the ‘For Sale’ and ‘Zoned Commercial’ signs . . . The only significant exceptions to unrestricted development have been the Cleveland and Akron Metropolitan Park systems and the area of the Cuyahoga Valley that we are considering today. In retrospect, it is evident that the Park systems resulted from the extraordinary foresight of a few our forefathers. This should be an example for today . . .”

He continued, “These Metropolitan Parks are fine—but they are not enough. There are just too many people, too little land, and the expectation of many more people in the future . . . The National Park Service is aware of the urban citizen’s need for freedom in the outdoors. How right they were in creating National Parks in the San Francisco Bay area and New York City. . . . If we are not decisive now, the curse of wall-to-wall urbanization will engulf this fragile valley. There will be no turning back.”

J. Arthur Herrick, leader of the Ohio Biological Survey, reminds everyone what is at stake: “This valley is truly a natural gem of great value . . . By whatever means may be devised, the present generation of Americans owe it to their heirs to see that this valley is saved for posterity. What we allow to be destroyed cannot be rebuilt.”

NPS Collection

Parks to People

The value and significance of Cuyahoga Valley cannot be separated from its position between industrial cities. Parts of the testimony focus on the Parks to People federal policy, launched in 1969, to protect open spaces in and around urban areas. US Congressman Louis Stokes (D-Ohio) states, “I represent nearly half a million Ohio citizens in Cleveland, the City of East Cleveland and Warrensville Heights. About 65% of my constituents live in the inner city. They have access to some lovely parks, Gordon and Rockefeller and a number of smaller ones. But except for the Cuyahoga Valley there is no place within 200 miles of Cleveland where nature is preserved in a condition very like the original wilderness. Few of my constituents will be able to enjoy such a place if something is not done to save the Cuyahoga Valley from encroachment by apartments and commercial centers.”

Delores Warren speaks on behalf of the League of Women Voters in Cuyahoga and Summit counties. She says: “With resounding unanimity, League members in both counties support the preservation and protection of the Cuyahoga Valley between Cleveland and Akron as open space/green area. The primary reason given for such support is the basic elemental need for green area in and around urban areas for the health of both the physical environment and the people themselves. Special notice was taken of the fact that a park would provide many recreational opportunities, would preserve a rich historical heritage, would save a fragile and significant ecology and many kinds of wildlife. The member mandate is emphatic: acquire the land—as soon as possible—in any and all possible ways.”

Local people would not be the only ones to benefit. A letter from the Sierra Club states, “We must not lose sight of the fact that more people will use the Park than the four million residents who live within a half hour drive, impressive though that statistic is. The Valley is spanned by major highway crossings, and is very close to the transcontinental web of interstate highways. Many visitors can be expected to benefit from the natural and historical virtues of the Cuyahoga Valley as they travel from origins and to destinations that are very far from northern Ohio.” Notice that the idea of Cuyahoga Valley becoming a tourist destination was too big of a dream back in 1974.

Arguments Against CVNRA and Supporter Rebuttals

The Nixon Administration is against federal protection for Cuyahoga Valley. It cites several reasons: financial constraints, a belief in limiting the federal government’s role in land protection, and questions about national significance. It advises that Cuyahoga Valley be placed under state and local protection. It notes that the federal government is already providing support via the Land and Water Conservation Fund.

This position was articulated by James Watt, director of the Bureau of Outdoor Recreation (BOR) within the US Department of the Interior. In his statement, Watt says, “The Bureau looks to the State for developing a recreation plan, for the development of this area. The plan has been submitted and has been looked upon with great favor. It is a good job. And the State, then is committing itself to acquire and eventually develop these lands for park and recreation services to serve these 4 million people of that area.”

The administration considered the proposed national park unnecessary. Watt continues, “the Federal Government, the State of Ohio, and the Akron and Cleveland Metropolitan Park Districts have already joined together in a viable, farsighted program for the Cuyahoga Valley. This program will create a locally administered Cuyahoga River Valley Park comprising some 14,500 acres. The Bureau of Outdoor Recreation recently approved the first two stages of a land and water conservation fund grant project whereby 6,212 acres will be acquired by the Cleveland and Akron Metropolitan Park Districts . . . We believe this existing combination of BOR financial planning and technical assistance, and the State and local efforts will protect the unique and valuable natural resources of the Cuyahoga Valley from urban development and accompanying environmental deterioration. This type of cooperation at all levels of government and with the private sector is essential in meeting the pressing demands for public outdoor recreation opportunities. We are excited with the great success of the existing cooperative program for the Cuyahoga Valley, and strongly believe it should not be abandoned.”

Ohio Governor John Gilligan rebuts this financial argument. In his statement, he says, “While the principal reason we in Ohio favor national park status for the Cuyahoga Valley is that we feel the proposed area richly merits the recognition which accompanies that lofty status, we cannot deny the financial burden which federal maintenance and operation lifts from Ohio taxpayers.” William Nye, director of the Ohio Department of Natural Resources, agrees with Gilligan. “Politically, you have to understand that in the State legislature there are other demands for state park development throughout the State . . . I cannot guarantee that in the future that we will be able to concentrate $4 million a year of State money. I doubt very much if we will.”

Congressman Seiberling presses the administration on whether their main objection is based upon budgetary considerations. Stanley W. Hulett, deputy director of the Bureau of Outdoor Recreation, testifies, “I do not think it is that at all. I think it is philosophical more than it is budgetary . . . At some point, Mr. Seiberling, you have got to say, when does the Federal Government get out of it? When do the local units of government get into it? Certainly this is a magnificent area—I have visited the area myself; I will be visiting it again in a couple of weeks with the Senate committee. There is no question that it needs to be preserved, and it is a great opportunity for the 4 million people in the area. What about St. Louis? What about Chicago? What about Dallas? What about Houston? What about Denver? You could go right down the list, and at some point, the Federal Government has got to say, wait a minute. And the Secretary of the Interior has determined that point is now.”

The administration’s final point is whether Cuyahoga Valley is worthy of being part of the National Park System. Watt says, “we feel this is basically a regional, local park, and does not have the national significance that some of the other brilliant additions to the Park Service has.” Representative Seiberling replied that, “We feel, for the reasons I elaborated on in my statement, that once this becomes nationally recognized by our national government, that it will also obtain national significance, because we think that the values are there and the interest is there.” Seiberling later adds, “I get the impression that the phrase ‘national significance’ is rather a flexible one, and what it comes down to . . . depends on the shifting priorities within the Department at that particular time. Because obviously, anything that the Department designates as of national significance is, by that very fact, of national significance.”

Broad Support

Success would rely on support at the local, regional, and national levels. Congressman Charles Vanik (D-Ohio) says, “I might point out that perhaps nowhere, and in no other project of this type that has come before the committee, has there been such strong local support for park development.” Congressman William Minshall (R-Ohio) adds, “More important than the legislators', the government officials' and the environmentalists' opinions on the need for a park, is the people's desire for a park and recreational area. I have, as I am sure my fellow Ohioan colleagues have, received numerous letters urging my support for this project.” For example, supporters present a petition with 10,000 signatures. There are dissenting local voices too, such as the resolutions by Northampton and Sagamore Hills townships opposing the park.

The following is a list of the organizations and individuals who submitted testimony or letters during the 1974 Congressional hearings on March 1, April 8, and June 8.

- John Ballard, mayor, city of Akron, Ohio

- John A. Begala, city councilman, city of Kent, Ohio

- Clarence J. Brown, US representative, Ohio

- John J. Gilligan, governor, State of Ohio

- John Glenn, Columbus, Ohio

- Tennyson Guyer, US representative, Ohio

- Troy Lee James, state representative, Ohio

- Dave Johnson, mayor, city of North Canton, Ohio

- Howard Metzenbaum, US senator, Ohio

- David C. Meyer, mayor, city of Navarre, Ohio

- William E. Minshall, US representative, Ohio

- Ohio House of Representatives, joint resolution

- Ralph J. Perk, mayor, city of Cleveland, Ohio

- Robert J. Quirk, mayor, city of Cuyahoga Falls, Ohio

- Elsie Reaven, councilwoman, Akron, Ohio

- Ralph Regula, US representative, Ohio

- Mark Ross, mayor, city of Massillon, Ohio

- Sherman 0. Schumacher, Akron, Ohio

- John Seiberling, US representative, Ohio

- James V. Stanton, US representative, Ohio

- Louis Stokes, US representative, Ohio

- Seth Taft, commissioner of Cuyahoga County, Ohio

- Charles A. Vanik, US representative, Ohio

- Winfred Wisnieski, mayor, city of Independence, Ohio

- George J. Wrost, director of public properties, city of Cleveland, Ohio

- American Rivers Conservation Council

- AMP Hike Club

- Blackbrook Audubon Society

- Buckeye Trail Association

- Citizens for Land and Water Use, Cleveland Metropolitan area

- Committee on Preservation of the Environment (COPE)

- Golden Lodge Local 1123, Conservation Committee

- Hale Homestead

- Hudson Heritage Association

- Institute for Environmental Education

- Izaak Walton League

- Izaak Walton League, Akron Women's Chapter

- Izaak Walton League, Western Reserve Chapter

- Kent Environmental Council, Kent, Ohio

- Lake Erie Watershed Conservation Foundation

- Midwest Railway Historical Foundation

- National Audubon Society

- National Parks and Conservation Association

- National Wildlife Federation

- Ohio Audubon Council, Canton, Ohio

- Ohio Conservation Congress

- Ohio Conservation Foundation

- Ohio Department of Natural Resources

- Ohio Parks and Recreation Association

- Old Trail School, Ecology Club

- Park Conservation Committee of Greater Cleveland

- Portage Trail Sierra Club

- Sierra Club

- Sierra Club, Northeast Ohio Group

- Sierra Club of Ohio-State Chapter

- Valley View Historical Society

- Wilderness Society

- Western Reserve Historical Society, Cleveland

- Akron

- Berea

- Broadview Heights

- Cleveland

- Cuyahoga Falls

- Garfield Heights

- Hudson

- Lakewood

- Macedonia

- Middleburg Heights

- North Royalton

- Richmond Heights

- Shaker Heights

- Valley View

- Akron and Summit County Federation of Women's Clubs

- Akron Chamber of Commerce

- Akron Garden Club

- Akron Jewish Center

- Akron Labor Council

- All City Kiwanis Club of Akron

- American Institute of Architects, Cleveland Chapter

- American Institute of Planners, Ohio Chapter

- American Society of Civil Engineers, Akron Section

- American Society of Civil Engineers, District Council

- Bath Township Board of Trustees

- Braewick Circle Garden Club, Akron, Ohio

- Britton Realty Co.

- Canal Society of Ohio

- Citizens for Air, Land & Water Use, Akron, Ohio

- Cleveland Executives Association

- Cleveland Growth Association

- Cleveland Regional Sewer District

- College Club Garden

- Committee on Electrical Power Transmission

- Council of the city of Kent, Ohio

- Cuyahoga County Mayors and City Managers Association

- Cuyahoga County Regional Planning Board

- Cuyahoga Valley Association, Peninsula, Ohio

- Cuyahoga Valley Park Federation

- Explorer Post

- Firestone Tire & Rubber Co.

- Golden Lodge Local

- Greater Cleveland Growth Association

- Junior League of Akron

- Junior League of Cleveland

- Keel-Hauler Canoe Club

- Lake Shore Garden Club, Euclid, Ohio

- League of Ohio Sportsmen

- League of Women Voters of the Cleveland Area

- League of Women Voters of Cuyahoga County

- League of Women Voters of Cuyahoga Falls

- League of Women Voters of Cuyahoga Valley

- League of Women Voters of Hudson

- League of Women Voters of Westlake-North Olmsted

- Little Miami, Inc., Lebanon, Ohio

- Musical Arts Association and the Blossom Music Center

- Nordonia Hills Community Roundtable, Northfield, Ohio

- North Hill Garden Club of Akron

- North Hills Water District, Summit County, Ohio

- Northeast Ohio Areawide Coordinating Agency

- Northern Ohio Urban System Research Corp.

- Ohio American Revolution Bicentennial Advisory Commission

- Ohio Council

- Republican Women's Garden Club of Portage Lakes, Ohio

- Robert L. Hunker Associates

- Sagamore Greenwood Community Association Inc.

- Summit County American Party

- Summit-Portage County Comprehensive Planning Agency

- Tri-County Regional Planning Commission

- Union Grange #2380 of Peninsula, Ohio

- United Steelworkers of America #1123

- West Shore Unitarian Church, Social Concerns Committee

- Western Reserve Girl Scout Council

- Akron Beacon Journal

- Cleveland Plain Dealer

- Cleveland Press

- Sun Newspapers of Cleveland

- Akron Metropolitan Park Board

- Akron Metropolitan Park District

- Centerville-Washington Park

- Cleveland Metropolitan Park District

- Cuyahoga Park and Recreation Board

- Hancock Regional Park District, Board of Park Commissioners

- Toledo Area Metropolitan Park District

- Stark County Metropolitan Park Commission

- Stow Park and Recreation Board

- Akron School Board

- Brecksville-Broadview Heights Council, PTA

- Brecksville Senior High School, PTA

- Cleveland City School District Board of Education

- Cleveland State University

- Cleveland Teachers Union

- College of Wooster

- Copley Junior High

- Cuyahoga Community College

- Independence High School

- Independence Local Schools, Board of Education

- Hudson High School

- Kent State University

- North Olmsted High School

- Northeastern Ohio Universities, College of Medicine

- Old Trail School, Bath, Ohio

- Parma Board of Education

- St. Edwards High School

- University of Akron

- University of Akron, Survival Center

What Makes the Difference

The creation of Cuyahoga Valley National Park is a yearslong process that came about through the collective efforts of thousands of people from many parts of society. The hearings, testimonies, and visits garner enough support to ensure that the park establishment legislation would advance. The critical role of these early advocates cannot be overstated—the park simply wouldn’t be here today without them.

In summary, four factors make the difference in getting the park legislation across the finish line.

The threat of suburban sprawl

Park support is fueled by a feeling that Cuyahoga’s Valley’s pastoral landscape will soon be overwhelmed by suburban development. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, advocates argue that it was now or never for creating the national park.

The new Parks to People federal policy

The federal “Parks to the People” campaign launches in 1964 and echoes throughout the Civil Rights era. It sought to preserve nationally significant natural and cultural areas close to population centers. Cuyahoga Valley met the criteria, but the federal government was reluctant to expand the new “national recreation area” concept beyond a few pilot parks.

Widespread public support at the local, regional, and state levels

Hundreds of organizations and individuals lend their voices for the movement to protect Cuyahoga Valley from development. This grows to a critical mass, exemplified by the amount of park support expressed at three congressional briefings. These take place in Peninsula, Ohio, and Washington, D.C.

Political efforts spearheaded by Congressman John F. Seiberling

Rep. Seiberling’s ability to get backing from both sides of the political aisle leads to numerous Congressional co-sponsors of the park’s enabling legislation. Rep. Ralph Regula (R-Ohio) and Rep. Charles Vanik (D-Ohio) are key allies in this bipartisan coalition building.

The Ohio delegation’s united front proves its strength at the eleventh hour when the bill is headed to a veto during the winter holidays. The park’s legislative history, A Green Shrouded Miracle, describes what happened in late 1974. “On December 27, President Gerald R. Ford received two urgent telephone calls in connection with the CVNRA bill. One was from Senator Howard Metzenbaum. Ford commented that his advisors wanted him to pocket veto it and asked Metzenbaum why he thought that should not be done. Metzenbaum replied that signing H.R. 7077 would be consistent with the nation's energy conservation goals with Ohioans staying in their own backyard instead of traveling to national parks in the west. Senator Robert Taft, Jr., was the second influential caller to ‘plead Ohio's case.’ Taft is credited with warning the president of the political consequences. Specifically, if Ford did not sign the bill, he would lose Ohio in the upcoming 1976 presidential election.”

New Research on National Significance

Ronald Thoman, the first chief of interpretation and visitor services, articulates the early view of why Cuyahoga Valley should be a national park. His emphasis is the park's accessibility and the preservation of resources that reflect Midwest life. He says, "Cuyahoga has often been criticized that we are not of national significance, that we don't have the monumental and superlative features in this park. . . . There is something about the miracle of the common that is very important . . . That is what Cuyahoga preserves . . . the slice of life, the flow of human endeavor, the blending of human and natural activities and landscapes, this harmony of man and nature on an everyday basis. In the Cleveland of the year 2050, I am not so sure it is going to be important for that urban child to be able to go out on the weekend and see the Grand Canyon, as it is important to go out and be able to touch the earth and touch the past and see the way things were." Notice that it is hard to imagine back in the 1980s how inspiring it will become to restore and better understand these resources. Some "history" such as the Cuyahoga River's role in the modern environmental movement is too recent to even be considered.

In 2000, Congress changes the name of Cuyahoga Valley National Recreation Area to Cuyahoga Valley National Park. Gradually, this attracts more people from distant places and raises the park’s profile locally, regionally, and nationally. Planning starts to improve the experiences of first-time visitors. This includes new research into the national significance of our key resources—particularly the Ohio & Erie Canal and the Cuyahoga River—and our role as an urban national park. What we learn is reflected in three large exhibit replacement projects (Canal Exploration Center, the Towpath Trail waysides, and Boston Mill Visitor Center) as well as the celebrations of Cuyahoga 50 in 2019 and CVNP 50 in 2024-25. In 2024, we complete a major revision of our Interpretive Theme Framework, spelling out the park’s big ideas and stories.

Learn More

Walk to the Founders Waysides beside Everett Covered Bridge to learn more about the contributions of Rep. John F. Seiberling and Rep. Ralph Regula. We also have exhibits on park establishment history at Boston Mill Visitor Center.

Visit the locations of the June 1974 US House subcommittee field trip: Hale Farm & Village, Stan Hywet Hall & Gardens, Stumpy Basin (south of Boston), and the Canal Fulton Canalway Center. Catch a concert at Blossom Music Center, the location of the second US House subcommittee hearings.

Read about our Foundation Document and Interpretive Theme Framework for information on the national significance of Cuyahoga Valley. A Green Shrouded Miracle documents our legislative history.