Last updated: August 27, 2024

Article

Checking Redwood's Vital Signs

Courtesy Jessica Weinberg-McClosky

Klamath Network Science

National parks are guardians of American natural and cultural history. But more than ever before, parks exist in rapidly changing landscapes. Urban growth, replacement of native species by exotics, air and water pollution, increasing visitor use, and climate change all impact the natural web of life. This leads us to ask:

How healthy are our parks?

How are they changing?

To answer these questions, the National Park Service grouped parks into 32 Inventory and Monitoring Networks. Starting in 2008 at Redwood National and State Parks and other nearby parks, the Klamath Network phased in monitoring of select natural resources. These “vital signs” are indicators of park condition. We track status and trends in these indicators by repeatedly visiting fixed sampling sites. This information supports park managers’ efforts to make science-based decisions.

What Do We Monitor at Redwood National and State Parks?

Courtesy Jessica Weinberg-McClosky.

Land Plants and Early Detection of Invasive Species

Redwood’s plant communities are complex, full of life, and extremely productive. Coast redwood forests boast the tallest trees on Earth! They are also powerful carbon sinks, meaning they store more carbon than they release. Understory gems like the trillium (Trillium ovatum) and redwood sorrel add diversity and support a variety of wildlife. In addition, the redwood forest, oak woodlands, and grasslands in the parks are culturally significant to the local Tolowa, Yurok, and Chilula people. But disturbances, like invasive species, disease, and lack of fire, can ripple through ecosystems. Drought exacerbated by climate change threatens the long-term survival of moisture-dependent redwood groves. To track vegetation community health, we monitor plant abundance and diversity. We also track woody debris conditions that are closely tied to fire.

NPS

While native plants thrive in the park, invasive exotics (plants that evolved in a different place) do occur. These include jubata grass and English ivy (Hedera helix). Invasives can outcompete native plants, monopolize water, and change the soil. We survey high traffic areas in the park where invasive plants most commonly appear to alert park managers to infestations.

Some resources we measure:

-

cover and diversity of native plants

-

cover and diversity of exotic, invasive plants

-

regeneration, by tree seedling counts

-

mortality, by counting recently dead trees

-

fuel availability, by measuring woody debris and litter and duff depths

- live tree characteristics, like volume (basal area), canopy health, and height

Learn more and find recent publications:

https://www.nps.gov/im/klmn/vegetation.htm

https://www.nps.gov/im/klmn/invasives.htm

NPS

Aquatic Communities

Wet areas abound with life, from the tiny aquatic insects that feed salamanders and bluebirds, to the lush greenery sought by wildlife. Amphibians thrive in Redwood’s streams. The endemic southern torrent salamander lives in Godwood Creek, one of the few remaining examples of undisturbed old growth forest stream habitat. The parks’ streams also support threatened salmonid fish, like steelhead trout and coho and chinook salmon. But the parks’ waters are vulnerable to climate change and other stressors, like the ever-present threat of invasive species or diseases. Water diverted by upstream activities, like agriculture, leaves streams shallower and warmer. Soil eroding off old timber roads degrades stream bottom habitats. We monitor the parks’ streams and the Freshwater Lagoon to track aquatic health.

NPS

Some resources we measure:

- water quality, like oxygen, pH, and turbidity

- water chemistry, like nutrients (nitrogen, phosphorous) and salts

- water quantity, like streamflow and the depth of ponds

- habitat features, like streamside vegetation and in-stream woody debris

- biodiversity, including fish, amphibians, algae, and aquatic macroinvertebrates (stream bugs)

Learn more and find recent publications:

https://www.nps.gov/im/klmn/streams.htm

https://www.nps.gov/im/klmn/lakes.htm

NPS

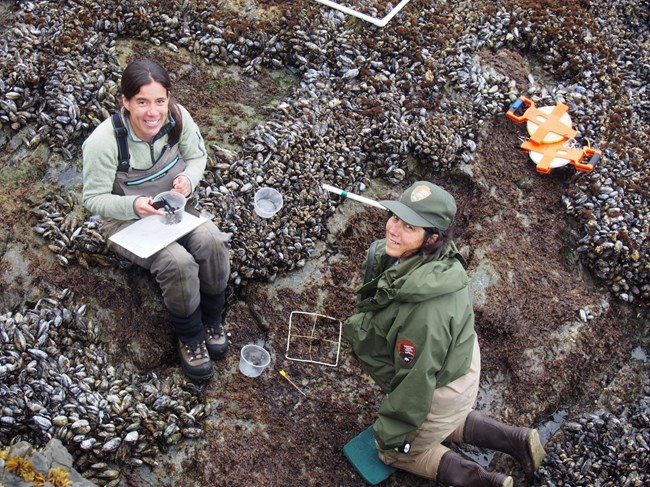

Rocky Intertidal Community

Plants and animals of the rocky intertidal shoreline face constant change, where splash zones shift to dry zones with the ebb and flow of the tide. They also face human-caused stresses, like oil spills, logging debris, and climate change-exacerbated ocean warming. Colorful purple and orange ochre sea stars (Pisaster ochraceus) are slowly recovering from a 2013 outbreak of Sea Star Wasting Syndrome on the West Coast. We collaborate with UC Santa Cruz scientists to monitor these sea stars, along with other shoreline organisms and conditions. Our findings support park management and contribute to the Multi-Agency Rocky Intertidal Network (MARINe), which tracks intertidal community conditions up and down the Pacific coast. We also share intertidal monitoring information on Tolowa and Yurok Ancestral territories with local Tribes.

Some resources we measure:

- invertebrate populations (sea star, snail, chiton, limpet, mussel, and crab)

- algae and surfgrass populations

- sea surface temperature

- presence of humans, trash, select birds, marine mammals, and other species of interest

Learn more and find recent publications:

Frank Lospalluto, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Birds

Birds delight us with song and beauty, but also with scientific data! Easily detected, they are good indicators of ecological health because they respond quickly to environmental change. Songbirds are critical to park health, spreading seeds and pollen across the land. Vultures scavenge carcasses to complete the cycle of life. Partnering with the Klamath Bird Observatory, we monitor landbirds at Redwood, like the cryptic brown creeper. This master of disguise looks like a moving piece of bark, spiraling its way up tree trunks to pluck spiders and other invertebrates from deep cavities in the bark of mature trees. Listen for its thin, high-pitched song. Our bird monitoring tracks the distribution and abundance of park birds and adds to regional landbird projects like the Avian Knowledge Network Northwest.

During the breeding season in June, we count birds along transects to determine

- the diversity of species present

- the relative abundance of each species

Learn more and find recent publications:

More Information and Vital Sign Publications

Klamath Inventory and Monitoring Network

Download a printable pdf of this article.

Prepared by Sonya Daw and the Klamath Network staff.

Listing photo credit: Jessica Weinberg-McClosky