Last updated: January 22, 2024

Article

Charlestown Navy Yard: Dry Dock 1

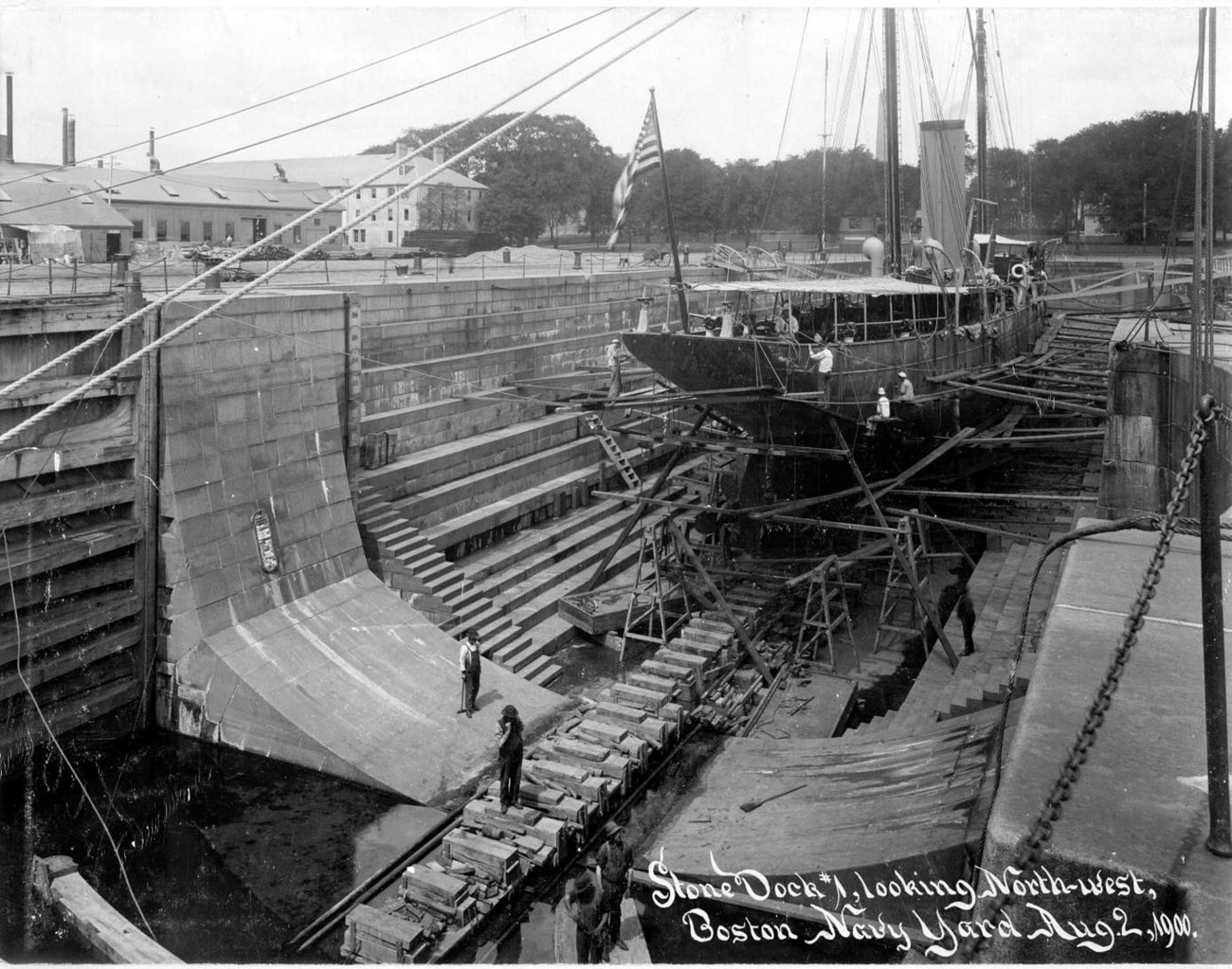

Boston National Historical Park, BOSTS 14208-1

Subject to the Tides

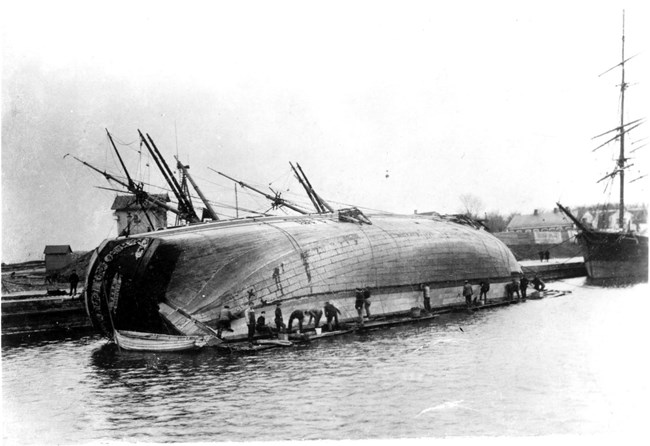

Boston National Historical Park, BOSTS-14543

During the Age of Sail, it was possible to operate a navy yard without a dry dock. Many repairs required little more than a pier and a simple crane. Accessing the lower hull was also possible, but more challenging. Small vessels might be pulled out of the water for hull repairs. Larger ships, however, had to undergo a process called "careening." Using ropes and the help of the tides, ships could be purposefully positioned and left "high and dry" on a beach, tilted to one side. The shipyard workers then repaired and cleaned one side of the hull at a time.

While somewhat inelegant and labor intensive, careening and other workarounds required little investment. The small US Navy of the early 1800s continued to manage during these early years without dry dock facilities, even when the larger British and French navies established dry docks more than 250 years prior.

The expansion of the US Navy during the War of 1812, however, made waiting on the tides in order to repair a growing number of ships unacceptable. The Navy's commitment to maintaining its larger fleet triggered the overall expansion of navy yard facilities and the construction of the first American drydocks.

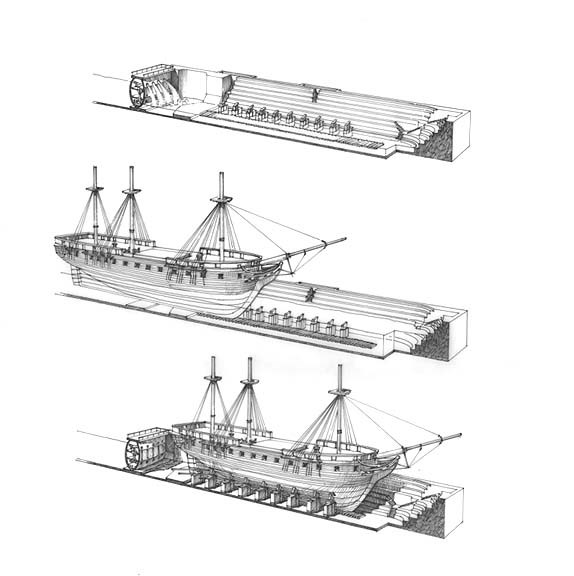

- Filling the basin: sea water flows into the dry dock until it is level with the harbor.

- Bringing in the ship: The caisson is pumped dry, floated, and towed away. The ship enters.

- Placing the ship: The caisson is towed back, flooded, and sunk. Pumps drain the dry dock and the ship settles on blocks.

NPS Illustration

Granite Bathtubs

In concept, a dry dock is quite simple. It is, in essence, a large basin attached to a body of water. When full with water, the basin can be opened and a ship can be maneuvered inside. Shipyard workers then close the dry dock and drain the water, leaving the ship resting on keel blocks.

However, creating a watertight space large enough for a ship is a real engineering challenge. When the Navy received funding for its first dry docks, civil engineer Loammi Baldwin Jr. took advantage of several new technologies. Most notably, he conceived of a new design as well as a new system: the final dry docks would use steam engines to power the pumps that drained the basin. The country's first dry docks would be quite advanced for their time.

The Navy ordered two dry docks in 1827, one for the navy yard in Norfolk, Virginia, and one for Boston. Both were built with granite supplied by the quarries just south of Boston in the town of Quincy, Massachusetts. The large stone slabs formed a watertight basin, and the mouth was closed with a wooden hull called a "caisson." The caisson was built like a ship, but was small enough to fit in the mouth of the dry dock. Dry dock operators positioned the caisson to block off the dry dock from Boston Harbor before the steam pumps drained the water away.

Naval History and Heritage Command, NH 2136

Baldwin designed the practically identical Norfolk and Boston drydocks when the largest ships in the US Navy were wooden-hulled sailing ships such as USS Independence and USS Delaware. At under 200 feet in length, Delaware easily fit within the total 341-foot length of the Norfolk dry dock, and it became the first ship the Navy repaired in one of its new drydocks. The Boston dry dock opened just a few weeks later and USS Constitution entered on June 24, 1833 as the first ship repaired at the Charlestown Navy Yard using Dry Dock 1.

Over the next twenty years, the relatively small US Navy fleet made sporadic use of its new dry dock in Boston. Instead, the facilities were often used by commercial ships. This kept the dock in use and prompted a number of repairs and improvements. Even if the Navy did not often need its ships to come into the dry dock to repair damage, it still sought to maintain its repair capabilities if and when the need arose. This meant that as ships continued to grow in size, Dry Dock 1 needed to be expanded to keep pace.

Boston National Historical Park, BOSTS 8796-270

Brick by Brick

How does one extend a dry dock?

In the case of Dry Dock 1, shipyard workers undertook this challenging task the first time in 1858. Workers carefully numbered each of the granite blocks before excavating an additional 65 feet on the inland side of the existing dry dock basin. Then, using "small powder charges" (explosives), workers broke apart the masonry and one by one moved the blocks that same 65 feet inland. Using the engraved numbers on each block, workers rebuilt the head of the dry dock in the same order as they were originally set. They also added new stone, this time quarried from Cape Anne, Massachusetts, to fill the gap in the center created when the inland head of the dock moved.

Any original stones previously damaged or destroyed by the explosive charges were replaced, and the result was a dry dock 20% larger than the original 1833 construction. In the short term, this extension allowed Dry Dock 1 to accommodate larger ships built during and after the American Civil War. By the end of the 1800s, though, the Navy's new battleships grew even larger. This prompted the completion of the far larger dry dock—Dry Dock 2—in 1905.

Boston National Historical Park, BOSTS 8796-1367

While the large cruisers and battleships had to be repaired elsewhere, the more numerous destroyers and submarines that developed in the early 1900s proved a good fit for Dry Dock 1's capacity. Dry Dock 1 saw considerable use during World War I and World War II, both fitting out new ships and repairing those coming back to the United States after taking damage.

In 1947, Dry Dock 1 was extended a second time, this time seaward, in order to make space for the increasing length of the escort vessels it was charged with maintaining. When finished, the newly extended drydock measured 404-feet in length, the same length it remains today.

Throughout the 1950s and 60s, shipyard workers used Dry Dock 1 to work on destroyers like USS Cassin Young, (DD-793) for both regular maintenance and more major refits as required by the changing needs of the Cold War. The nearby sonar repair shop in Building 10 was well positioned to provide maintenance on the sensitive underwater detecting equipment on these ships before that shop moved to a larger facility in 1958.

When the Yard closed in 1974, Dry Dock 1 remained one of the few operational assets in the Charlestown Navy Yard. As part of the commitment to maintaining USS Constitution in Boston, Dry Dock 1 guarantees that maintenance can continue indefinitely. Since the addition of Cassin Young to Boston National Historical Park in 1978, Dry Dock 1 has played a critical role in maintaining both museum ships over the decades. Though Dry Dock 1 is itself nearly 200 years old, the preservation of the wooden-hulled frigate Constitution as well as the steel-hulled Cassin Young would not be possible without it.

Sources

Bearss, Edwin C. and Frederick R. Black. The Charlestown Navy Yard 1842-1890. Boston, Massachusetts: Boston National Historical Park, National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, July 1993.

Black, Frederick R.. Charlestown Navy Yard: 1890-1973, Volume I and Volume II. Boston, Massachusetts: Division of Cultural Resources, Boston National Historical Park, National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, 1988.

Brady, Mary Jane and Christopher J. Foster, Inc. Historic Structure Report Dry Dock I Charlestown Navy Yard Architectural Data. Boston, MA: Boston National Historical Park, National Park Service, U.S. Dept. of the Interior, 1980.

Brady, Mary Jane and Chirstopher J. Foster, Inc. Historical Structure Report: Dry Dock I Charlestown Navy Yard. Boston, MA: Boston National Historical Park, National Park Service, U.S. Dept. Of the Interior, 1980.

Carlson, Stephen P. Charlestown Navy Yard Historic Resource Study, Vol 1-3. Boston, MA: Division of Cultural Resources Boston National Historical Park National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior, 2010.