Last updated: March 14, 2024

Article

The Cabin Club/Drift Inn: A Black Getaway in Cuyahoga Valley

© Akron Beacon Journal – USA TODAY NETWORK

The Cabin Club was an African American retreat that operated in Cuyahoga Valley for at least a decade. Ohio business records show that it incorporated on August 12, 1946 and closed September 30, 1966, although it may have stopped operating years earlier. It was located just south of downtown Peninsula at 5360 Akron Peninsula Road, southwest of the Truxell Road intersection. The business was a music club, restaurant, and outdoor recreation center. It featured six cabins for overnight lodging, a baseball diamond, and barbeque pits. Orchestras and jazz musicians performed there as part of Northeast Ohio’s thriving jazz culture. The Cabin Club was about 22 miles from Cleveland and about 17 miles from Akron.

During this period, many recreational and entertainment facilities in Summit County, Ohio, and beyond only served white patrons. Much like the nearby Lake Glen, the Cabin Club operated during an era when discrimination was legal. African Americans resisted by finding joy, playing, relaxing, and making memories in spaces of their own. All businesses and public spaces were integrated by the Civil Rights Act of 1964, although people still needed to fight for social change.

This research is part of Green Book Cleveland, a collaborative project documenting Black history in Northeast Ohio. The Green Book was a Black motorist guidebook published 1936–66. Understanding sites supporting black travel and recreation is a priority of the African American Civil Rights Network.

The Complicated Property Story Begins

The story starts with the Great Migration which began in the early 1900s. African Americans moved in waves to northern cities for jobs and to flee Jim Crow laws in the South. John Lee was born in 1894 in Virginia and Helen A. Radley was born around 1900 in Alabama. They met in Ohio and married in Summit County in 1930. The Lees settled in the Peninsula area with their extended African American family. The other two last names are Harris and Duncan. The latter ran a small dairy farm, Duncan's Farm, which was also used for hunting parties and gatherings.

In 1937, according to deed records, the Lees bought 35 acres of land on Cuyahoga Valley Boulevard (now Akron Peninsula Road). The 1940 census said that they were living on their land with Helen’s mother and another married couple. They purchased 42 more acres nearby in the northwest part of Lot 32 in 1945. In 1942, Helen and John Lee bought another 12 acres on Cuyahoga Valley Boulevard. This smaller tract was sold three years later to David King.

The 12-acre property is where the Cabin Club was built on a bluff overlooking a bend in the Cuyahoga River. We don’t know the exact year, but the Summit County records hold some clues. In 1946, only a year after purchasing the land, David King sold two-thirds of his interest to Samuel Barner and Mitchell Wadley. He retained a one-third interest for himself. Samuel Barner and Mitchell Wadley were also the owners of the Ritz Plaza Hotel in Akron during this same timeframe. (In October 1945, the business partners took out a $13,000 loan for the Ritz Plaza.) In June 1947, the trio co-signed for a $4,500 mortgage for the 12-acre tract. This suggests that property improvements for the Cabin Club began. By October, King signed a deed giving full ownership of the property to Samuel Barner and Mitchell Wadley. Further improvements in the Cabin Club appear to have been made in the early 1950s, based on two mortgages ($3,700 and $10,300) that the partners obtained in December 1951 for both the Cabin Club property and the Ritz Plaza.

Newspapers.com/Cleveland Gazette (June 25, 1955)

Offering Sports and Family Fun

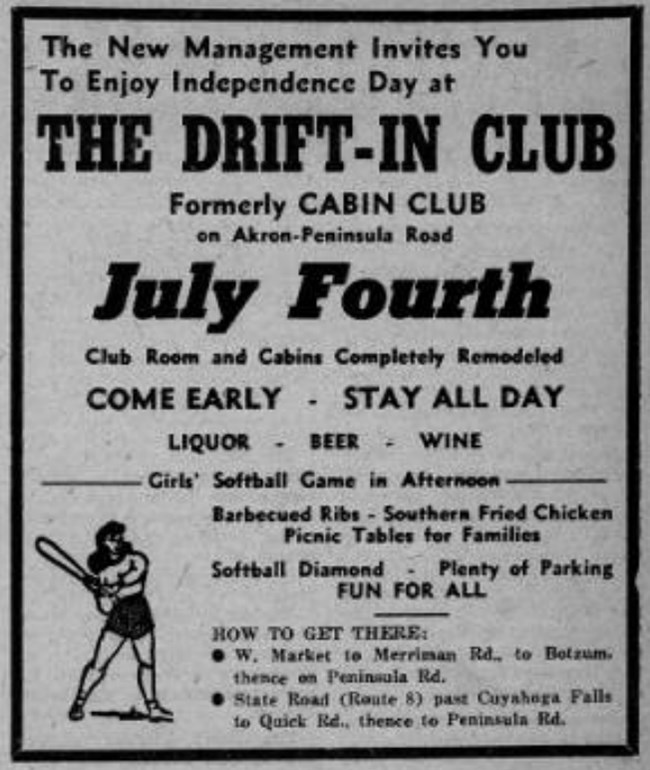

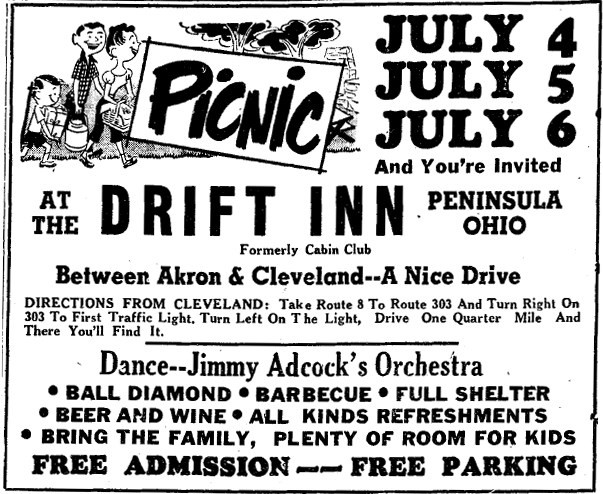

The Cabin Club (and later the Drift Inn) was promoted as a family friendly venue. The owners capitalized on baseball being America’s most popular sport. Beginning in 1947, the Cabin Club often advertised the Rhythm Bar Girls. This all-female amateur softball team was based at the club and also practiced in Akron. Their manager was Abe Atkins. His address is listed as 124 N. Howard Street, which is the Ritz Plaza Hotel and its Rhythm Bar. In a 1947 article, the Cleveland Call and Post reported, “On Sunday next August 17th the Rhythm Bar Girls play at Ashtabula. On the following Sunday, August 24th they play Painesville, then back here at home at the Cabin Club.” The article continues, “The present ball diamond will be converted into a tennis court when the much larger amphitheater diamond is completed. There is a very large parking lot, and plans call for play-ground equipment for the kiddies, so next year you can bring them along too. Be sure to be on hand at the Cabin on Labor Day as there will be a big surprise exhibited.” It is unclear from aerial photographs and newspaper records if these amenities were ever built.

In December 1954, Barner and Wadley granted a 2-year lease to Johnnie Guess for use of the 12 acres and the buildings. According to the lease, the premises were to be used for the purpose of selling alcoholic beverages. There was also a public camp and a shelter house, as well as cabins available for rent. Campfires were allowed on the property as long as they were kept safely secured. It appeared that Johnnie W. Guess (of 372 N. Arlington Street, Akron) changed the name to the Drift Inn and operated it as a bar and a place to recreate. Guess had an option to renew the lease for another four years after it expired. Instead, he opted to occupy the premises by paying a monthly rental fee, possibly up to March 1960.

Newspaper accounts said that both the Cabin Club/Drift Inn and the Ritz Plaza in Akron were seized for delinquent federal taxes and put up for sale. Property records showed that Samuel Barner and Mitchell Wadley sold the Cuyahoga Valley property in 1956 to Theodore Cage. Cage bought and sold numerous properties in Akron and was involved in the purchase of the Ritz Plaza during the same year.

Raids and Closures

Intense policing contributed to the club’s financial and legal troubles. Anti-vice campaigns swept America in the 1950s, disproportionately targeting minority communities. During this period, it was common for mainstream newspapers and Black newspapers to characterize Black businesses differently. The Cabin Club/Drift Inn was frequently raided by Summit County officials for illegal liquor sales, health code violations, and gambling. A 1951 raid caused 75 customers to flee. In its coverage, the Akron Beacon Journal said the club was a “notorious spot that has claimed the attention of sheriff’s deputies and state liquor agents on numerous occasions. . . . The club has been the target of repeated raids in recent years.” In 1952, the club was briefly forced to close due to illegal activity. In a 1957 article, the Cleveland Call & Post reported that local law enforcement closed the club for health code violations. The newspaper argued that this was deliberate racial discrimination. Ohio had just elected C. William O’Neill as governor. The article quoted O’Neill as saying, “If there is an obvious failure on the part of the local officials to suppress commercialized vice and if it begins to move in any area, then I as governor will use the authority vested in me by law to take appropriate action to see that it is driven out.”

The tense situation came to a head in the summer of 1957. On July 5, the Akron Beacon Journal reported that Charles “Lucky” Abraham was fatally stabbed by his girlfriend the previous night in a “drunken brawl” outside the Drift Inn. “The killing was the climax to a long series of disorderly conduct incidents and liquor and health violations at the Northampton twp. drinking spot, formerly known as the Cabin Club.” A related article quoted Chief Sheriff’s Deputy Gobel Waddell, “Sooner or later something like this was bound to happen. . . . We have wanted to close the place up for months.” Waddell “has had deputies checking out the place regularly since the first of the year.” Harvey Underhill, the health department’s chief sanitarian, added that “as far as he was concerned from here on out ‘there will be no leniency shown. We plan to close places like the Drift Inn as fast as possible and keep them closed.’”

Cleveland Public Library/Cleveland Call and Post (July 6, 1957)

Contrast this with how the Drift Inn advertised their July 4 weekend picnic, shown right.

On July 13, the Cleveland Call & Post argued that the Akron Beacon Journal’s focus on the stabbing was a deliberate distraction from the devastating July 1 fire at Stonibrook, three miles away. The fire was believed to be “an incendiary demonstration by a hate group. . .” No one was arrested. “The $30,000 fires, which could have been seen at Akron, got no notice in Akron newspapers, but a daily devoted an elaborate page layout to the Drift Inn ‘brawl slaying’ . . .”

Nearby Cuyahoga Falls used to have a reputation as a “sundown town.” (Today, it is racially diverse.) Scholarship about sundown towns and Black recreational history support the argument that the Cabin Club/Drift Inn, Lake Glen, and Stonibrook were all targeted because of their Black clientele. According to historian John Lowney, author of Jazz Internationalism, mid-1900s Black clubs were places for discussions of progressive Black ideas and expressions of sexuality and race. Fear of these ideologies and widespread racism were likely motives in the persecution of such businesses.

The lack of primary resources describing the Cabin Club/Drift Inn leaves us with many questions. For example, we are not sure when the business closed, and when and why the buildings were demolished. One clue might be the overhead powerlines that now cross the area. In 1946, David King signed a right-of-way to the Ohio Edison Company to construct, operate, and maintain lines for the transmission and distribution of electricity and the operation of telegraph and telephone line over, across, and above the 12-acre property. These were not built immediately. Peninsula Library & Historical Society has newspaper clippings that document the village’s unsuccessful legal fight to have these lines installed underground. A 1966 article describes land being cleared in Boston Township along easements which were purchased long before.

Learn More

For an overview of Black outdoor experiences in the 1900s, we recommend the National Park Service’s African American Outdoor Recreation: A National Historic Landmark Theme Study.

The Green Book Cleveland website documents many Northeast Ohio sites. Our park has also profiled Lake Glen, a similar business that was located at the edge of Cuyahoga Valley during the 1950s. More is known about Lake Glen and it appears to have been more popular.

Hikers and horseback riders can take the Valley Trail between Hunt House and Peninsula to cross through the Cabin Club/Drift Inn property. Long-term, Cuyahoga Valley National Park and its friends’ group plan to honor this history as part of the Brandywine Golf Course restoration project.

Is there a special place where you hang out with friends?