Last updated: September 5, 2025

Article

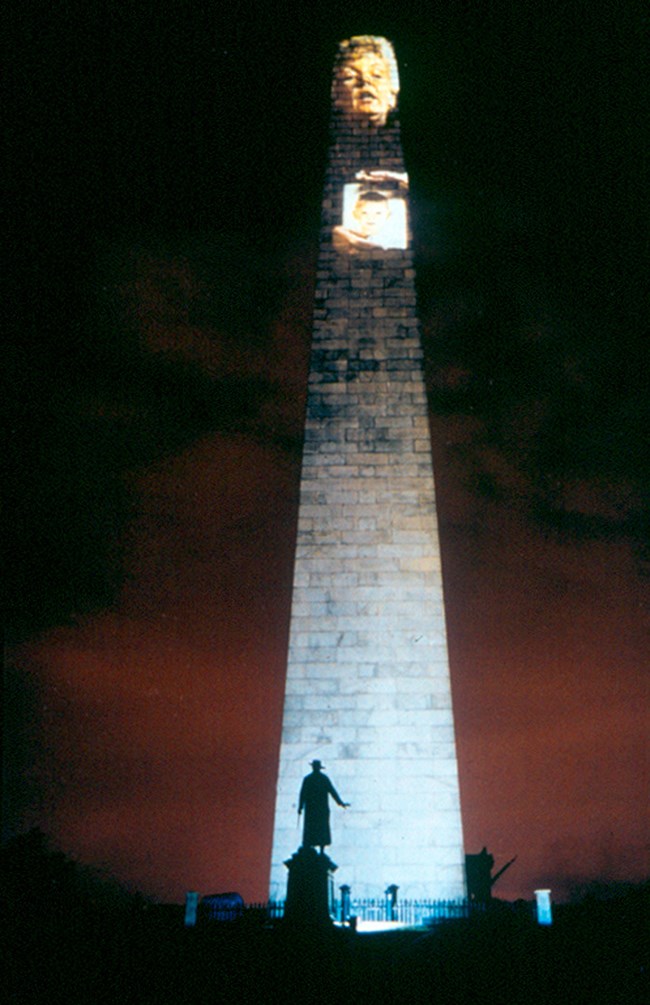

Bunker Hill Monument Projection, 1998

Courtesy of Institute of Contemporary Art

By meshing the monument and the mothers’ faces and words, [Krzysztof Wodiczko] reminds us that the struggle for freedom from tyranny goes on. And he lets the mothers’ pain animate stone that is normally as still and silent as the Sphinx.[1]

Over the course of three nights in late September 1998, the Bunker Hill Monument served a new role for many in the Charlestown community. It not only remembered the bloody past of those who died in pitched battle more than 200 years prior, it also witnessed the violent present of Charlestown. From September 24-26, a 19-minute projection lit the face of the monument with clips of mothers and brothers sharing stories of losing family members to street violence.[2]

About the Projection

Boston National Historical Park and the "Vitas Brevis" program of Boston’s Institute of Contemporary Art collaborated on this initiative to illuminate the Monument with the voices of present-day Charlestown. The Bunker Hill Monument projection was part of the "Let Freedom Ring" series of public art installations at several Boston historical sites.[3] The initiative commissioned MIT professor and artist Krzysztof Wodiczko to create this projection.[4]

Receiving international acclaim for his work, Wodiczko often challenged or redefined the meanings of the public spaces with his projections. The Bunker Hill Monument installation proved no different. Wodiczko looked to contemporary issues facing the Charlestown community as inspiration for his projection upon a symbol of the town’s revolutionary past. At this time, the mostly working-class community had experienced several decades of a high rate of violence, particularly murders. Many homicide cases remained unsolved due to a "code of silence."[5] As a result, many victims’ families never saw justice or closure for losing their loved ones. Wodiczko wanted to help community members break this code of silence. He remarked, "silence and invisibility are the biggest enemies of democracy...If you cannot speak, none of your other constitutional rights can be exercised."[6]

Wodiczko worked with Charlestown After Murder in this effort. Founded by mothers of victims, Charlestown After Murder served as a support group for family members of victims of violence. While at first hesitant and wary, members agreed to the project "after carefully considering the matter and being impressed by tapes of [Wodiczko’s] previous work."[7] Wodiczko and the group decided to record several mothers’ and brothers’ experiences with violence in the community.

For filming, Wodiczko had individuals sit on pedestals while they shared their stories. They held either candles or portraits of their loved ones. He then positioned the camera to look up at them to create the perspective of someone looking up at the Monument.[8] This intention in perspective meant "the obelisk literally [would appear] to come to life as a giant, well-proportioned person."[9]

Opening

Preparing for the projection’s opening on September 24, the Institute of Contemporary Art released a pamphlet that declared, "the Bunker Hill Monument will assert its First Amendment right and will speak freely of what it has seen and what it has heard."[10] For three consecutive nights, the Bunker Hill Monument projection ran four times a night starting at 8pm. Wodiczko remarked of the projection:

the huge images of [individual’s] faces [enlivened] the monument, and their painful confessions and testimonies [broke] the borough’s conspiracy of silence.[11]

Members of the local Charlestown and greater Boston communities gathered in Monument Square to watch the projection. Marty Blatt, supervisory historian for Boston National Historical Park at the time, recognized the symbolic significance of the projection on Bunker Hill Monument:

What could be more symbolic of freedom than these women who have lost their loved ones? It was the ultimate denial of freedom to have no one come forward. This was the most extraordinary moment I’ve ever seen in public art.[12]

Community Reception

Among the most unique installations at the Monument, this projection prompted debate with members of the Boston and Charlestown community. Some Charlestown community members felt "duped" by the project and its message. James Conway of the Charlestown Patriot newspaper believed it "unfairly tarred" the community. Real estate broker William Gavin remarked: "We were told this was going to reflect freedom and history. You tell me how the Charlestown code of silence is a universal theme?"[13]

Others, however, saw the project as a necessary jolt to awaken people to the violence and injustice happening in the community surrounding Bunker Hill. Boston journalist Christine Temin noted, "They are describing real events that happened there, and they demand you pay heed."[14] It forced a new meaning upon the monument, as Temin considered, "It will be hard for people who were at Bunker Hill last night to view the monument the way they did before."[15]

Despite the project’s mixed response locally, Wodiczko received praise for instilling new meaning on the Monument. Collaborating with Charlestown mothers and family members, Wodiczko "transformed a historical monument devoted to freedom fighters into a monument of contemporary heroes trying to fight violence."[16]

Wodiczko’s projection shows how the community can continue to create and find new meaning in the Bunker Hill Monument. Professor Sarah Purcell notes: "Wodiczko does not reject the commemorative purpose of the monument, but rather he layers a contemporary purpose on top of the marble meant to entomb the heroes of the Revolution."[17]

Footnotes:

[1] Christine Temin, "Monument message is searing," Boston Globe, September 25, 1998.

[2] "Bunker Hill," Krzysztof Wodiczko Projections, accessed March 2023, https://www.krzysztofwodiczko.com/public-projections#/bunker-hill/.

[3] In addition to the Bunker Hill Monument projection, "Let Freedom Ring" installations occurred at Old South Meeting House, Boston Common, and Old North Church. See Sarah J. Purcell, "Commemoration, public art, and the changing meaning of the Bunker Hill Monument," The Public Historian 25, no. 2 (2003) 60.

[4] "Wodiczko's Bunker Hill Projection Opens," MIT News, September 23, 1998. Accessed March 2023, https://news.mit.edu/1998/bunker-0923.

[5] Purcell, "Commemoration, public art, and the changing meaning of the Bunker Hill Monument," 58.

[6] "Wodiczko's Bunker Hill Projection Opens," MIT News.

[7] Purcell, 59.

[8] "Bunker Hill," Krzysztof Wodiczko Projections.

[9] Purcell, 69.

[10] As referenced in Purcell, 68.

[11] "Bunker Hill," Krzysztof Wodiczko Projections.

[12] "Contemporary Art Taps Vitality of Boston's Historic Sites," News Closeup: New Voice in Hallowed Places (National Park Service), accessed March 2023, https://www.nps.gov/crps/commonground/Fall2005/newscloseup.pdf.

[13] Judy Rakowsky, "Charlestown not silent on new movie, art project" Boston Globe, September 26, 1998.

[14] Temin, "Monument message is searing."

[15] Temin, "Monument message is searing."

[16] "Bunker Hill," Krzysztof Wodiczko Projections.

[17] Purcell, 61.