Last updated: September 29, 2025

Article

Breed's Hill versus Bunker Hill

"If this is Breed's Hill, then why is the battle called 'The Battle of Bunker Hill'?"

Rangers frequently hear this question from visitors to the Bunker Hill Monument, the memorial built to honor the lives of those who fought in one of the first Revolutionary War battles. Over 250 years later, let's explore how and why this confusion took root.

The short version of the story is like many others; it all comes down to small-town politics and local rivalries. The Bunker Hill Monument (where the colonists built fortifications during the battle) sits on what is officially named Breed's Hill. However, at the time of the battle, the hill was officially called Bunker Hill (with "Breed's Hill" being is local nickname.

(Pre)Colonial Naming Conventions

The Massachusett Tribe has lived in what is known today as Charlestown, as well as the neighboring areas, for thousands of years. Pre-colonization, native peoples referred to this place as "Mishawum," meaning "Great Springs." When the English settlers landed here in 1628, they renamed the area after their king, Charles I.[1]

In the colonial era, the naming (or renaming) of prominent geographic features by those with English origins was based on two factors: who first encountered the feature (thus "discovering" it) or who owned the parcel of land in the eyes of English Law.

Charlestown Geography

In 1775, the Charlestown Peninsula consisted of three prominent peaks that dominated the landscape. Morton's Hill, 35 feet above sea level, stood as the smallest hill and was located on the northeastern end of the peninsula.[2] Bunker Hill and Breed's Hills towered over the rest of Charlestown. The two peaks sit near the center of the peninsula with Bunker Hill to the west and Breed's Hill to the east. While today only Bunker and Breed's Hills still stand, the colonists knew all three hills as the "Charlestown Heights."

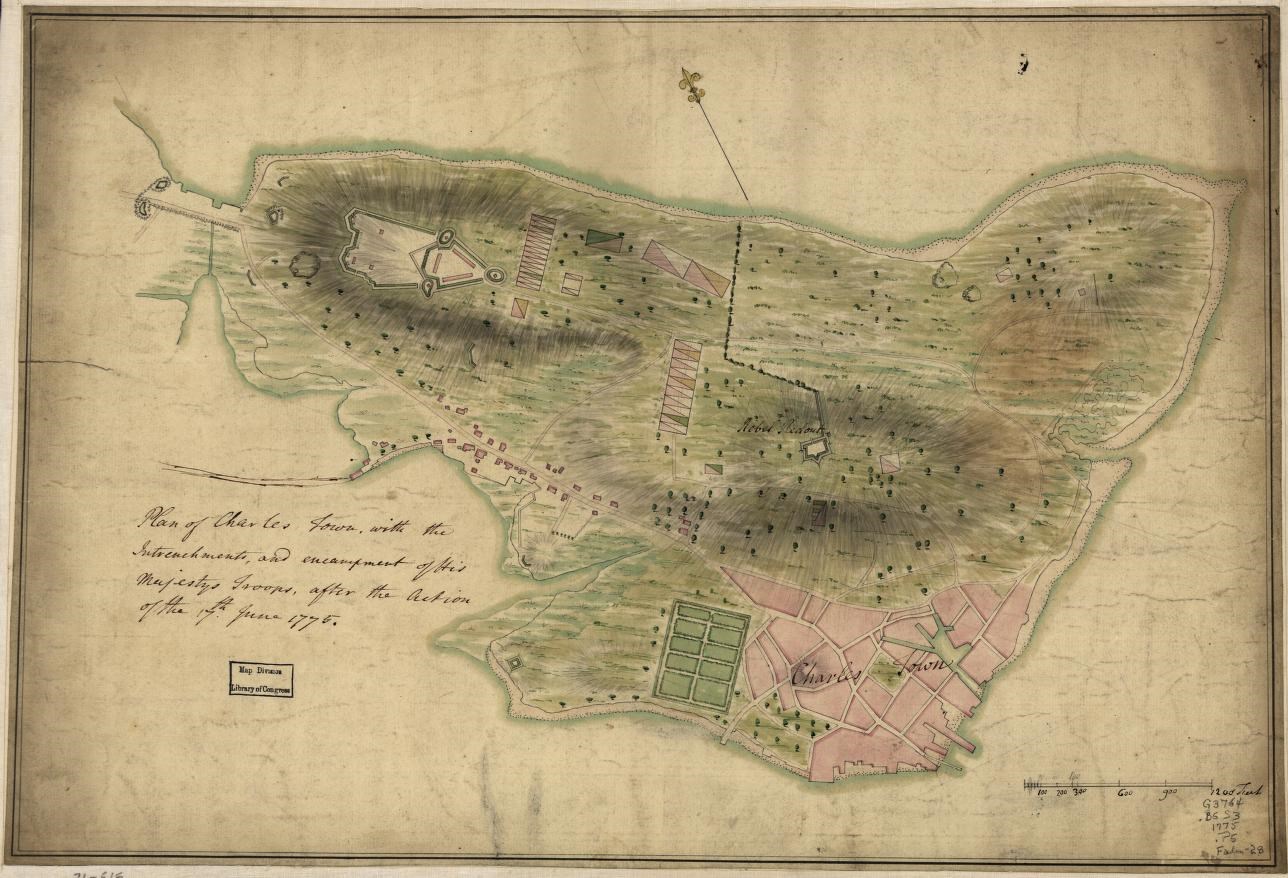

"Plan of Charles Town, with the intrenchments, and encampment of His Majesty's troops, after the action of the 17th. June 1775." Library of Congress.

However, Bunker and Breed's Hills should not be viewed as independent features. Geologically, the two are part of the same formation. They act as two peaks along a ridgeline that runs east southeast to west northwest. Between the peaks, they are connected by a shallow saddle (or dip) in the landscape. The highest point of what is officially called Bunker Hill today (currently occupied by St Francis de Sales Church), sat at 110ft above sea level. In contrast, Breed's Hill (where the Bunker Hill Monument is) measures 62 ft above sea level, and the hill remains that height today.

Confusion Takes Root

The confusion between the names of the two hills began with the initial settlement of Charlestown in the early 1600s. One of the first European settlers to stake a claim on the peninsula was a wealthy man by the name of George Bunker. Due to his ownership of land at the top of the heights, locals applied Bunker's name to the landscape. The ridgeline would come to be known as Bunker's Hill, Bunker's Hills, or some similar variation, soon shortened to simply Bunker Hill.[3]

Though the Breed family did not own any land on the hill itself at this point, they did use the fields near the shorter peak to graze their cattle. Ebeneezer Breed, another Charlestown resident, lent his name, unofficially, to the shorter peak. Some Charlestown and Boston locals took to nicknaming the hill after the Breeds.[4] Officially, though, the whole ridge would keep Bunker's name.

"View of the city of Boston from Breeds Hill in Charlestown / del. & engraved by S. Hill." Library of Congress.

The Battle of Bunker (Breed's) Hill

Fast-forwarding to the 1770s, the British Crown relied on Bunker Hill as an important feature for its defense of Boston. The hill played host to a small defensive work overlooking the Charlestown Neck (the only way by land to access the peninsula). The British constructed this fortification directly after the events of The Battles of Lexington and Concord on April 19, 1775. However, the Crown Forces quickly abandoned the position, choosing instead to consolidate their forces inside Boston, as colonial forces gathered outside. This action by colonial forces marks the beginning of The Siege of Boston.

Expecting a British attack out of Boston, intending to break the siege, Major General Artemas Ward of the Massachusetts Militia ordered Bunker Hill fortified. Yet, when Colonel William Prescott, Major General Israel Putnam, and Colonel John Stark arrived in Charlestown, they decided to instead fortify Breed's Hill.

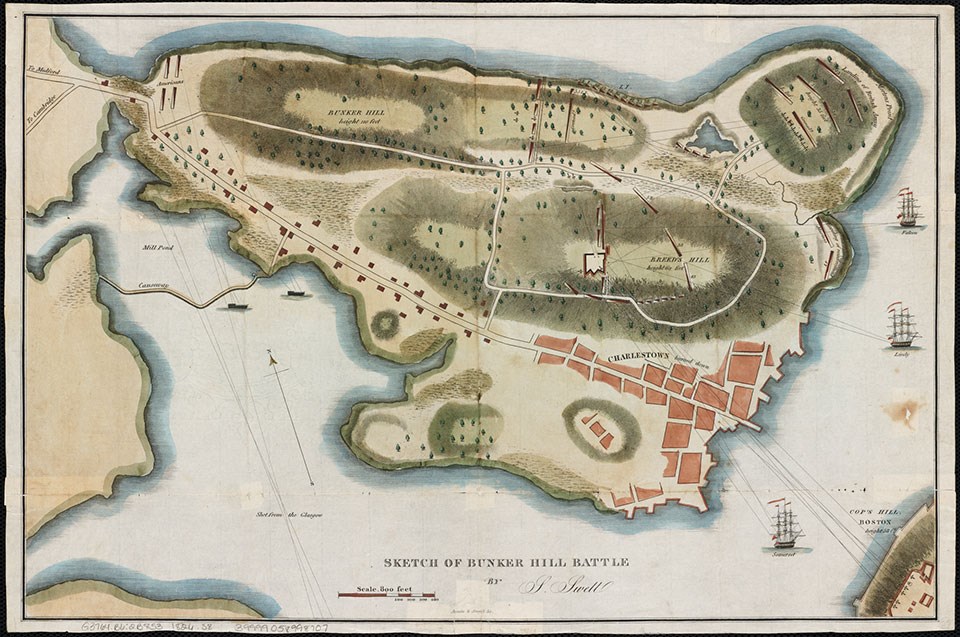

"Sketch of Bunker Hill Battle. "Boston Public Library, Norman B. Leventhal Map Center.

Although Breed's Hill was lower in elevation than Bunker Hill, it offered a tactical advantage. The hill had a steep slope for attackers to march up, while offering a gentle backslope in case the defenders needed to retreat. Breed's Hill was also tall enough to keep the defenders relatively safe from British cannons in the North End and on warships in the Charles River. Additionally, Breed's Hill was closer to the city of Boston than Bunker Hill. This proximity allowed the colonists to directly threaten the city with cannons.

It is also worth noting that after Lexington and Concord, some colonial leaders, like Putnam, wanted to instigate another battle. Building fortifications on Breed's Hill, in plain view of the city while flying flags that weren’t the Union Jack (see Flags of Bunker Hill), was a way for the colonists to provoke the British Army into an ill-prepared attack.[5]

Post Battle

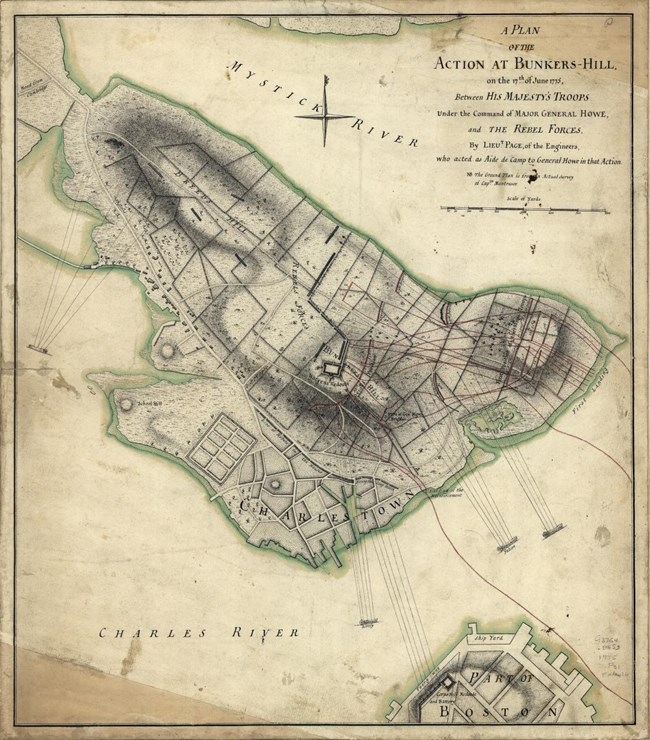

"A plan of the action at Bunkers-Hill, on the 17th. of June, 1775, between His Majesty's troops under the command of Major General Howe, and the rebel forces," Library of Congress.

After the Battle of Bunker Hill, the colonists attempted to rationalize how and why they lost. Realistically, the lack of resupply, limited reinforcements, and the absence of a rigid chain of command set up the colonial forces for defeat. Yet, in personal accounts, some colonists concluded that they believed officers had knowingly or unknowingly chosen the wrong hill to make a stand on. Whatever the case, confusion over the name of the hill where the battle raged had already taken root.

To further complicate matters, as the British were compiling their after-action reports, a clerical error, attributed to Lt. Page, mislabeled the two hills. A British map has the names of the two hills reversed, displaying Bunker Hill as Breed's Hill and vice versa.[6]

In the days and years immediately after the battle, the Breed Family attempted to have the battle renamed to "the Battle of Breed's Hill." But news of the battle had already gone to print, with the first officially published depiction by rebel officer Bernard Romans naming the battle "the late Battle of Charlestown." Others soon published accounts discussing the "Battle of Bunker Hill."[7]

The Metropolitan Museum, New York.

Bunker Hill became the centerpiece of the battle in many depictions, and thus its name was cemented. After all, the true prize for both sides at the end of the day was control over the highest ground on the peninsula (Bunker Hill). Whether any fighting actually occurred on it was irrelevant.

Additionally, the British soon ventured back into Charlestown to expand defensive works on Bunker Hill, built on April 19. They constructed a redoubt much larger than the colonists had on Breed's Hill, but abandoned it as winter set in. Charlestown would remain a no man's land until the end of the Siege of Boston on March 17, 1776.

A Continuing Debate Put to Rest

The Breed Family's attempts to write themselves into the historical narrative reignited after the end of the American Revolution. In the 1790s, the Breed Family finally bought land atop Breed's Hill, turning the local nickname of the hill into its officially recognized name. Once again, they approached the state government, but the Breed family's requests to have the battle renamed were in vain.[8]

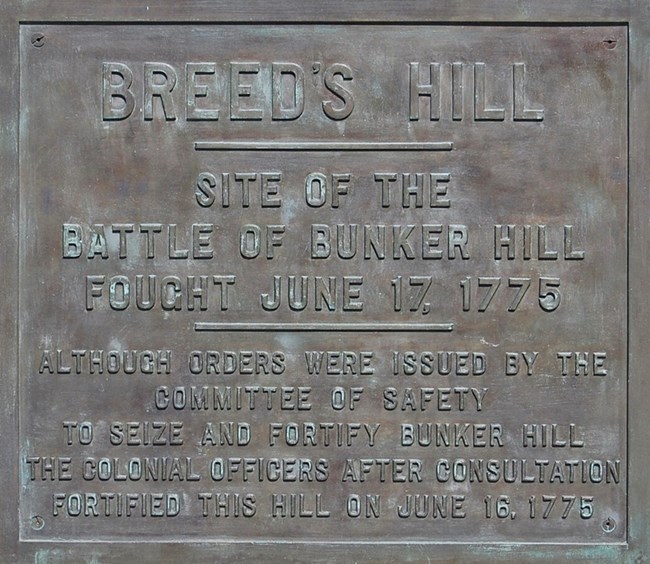

After decades of petitioning from the Breed Family, the Massachusetts State Government made an alteration to the façade of the Bunker Hill Lodge in 1923.[9] On the eastern outer wall of the lodge, the plaque pictured can be seen today; it reads:

NPS Photo

Breed's Hill

Site of the Battle of Bunker Hill Fought June 17, 1775Although Orders Were Issued By The Committee of Safety To Seize and Fortify Bunker Hill The Colonial Officers After Consultation Fortified This Hill on June 16, 1775

Today, the National Park Service is proud to steward this sacred ground and the Bunker Hill Monument that stands to commemorate the battle. Rangers on the hill welcome visitors to ask them any questions about the battle or the monument, even the age-old question, "If this is Breed's Hill, then why is the battle called 'The Battle of Bunker Hill'?"

Contributed by: Collin "CJ" McLaughlin, Park Ranger

Footnotes

[1] “New Harborwalk Signs in Charlestown,” Boston Harbor Now, January 28, 2019, https://www.bostonharbornow.org/new-harborwalk-signs-in-charlestown/; Patricia Quintero Brouillette and Margaret Coffin Brown, "Bunker Hill Monument Cultural Landscape Report for Boston National Historical Park," Olmsted Center for Landscape Preservation (National Park Service: Boston, Massachusetts, 2000), https://npshistory.com/publications/bost/clr-bunker-hill-mon.pdf.

[2] Casimer Rosiecki, "Fields of Deception," National Park Service, accessed September 25, 2025, https://www.nps.gov/articles/bunker-hill-battlefield.htm.

[3] Bette Bunker Richards, "George Bunker of Charlestown Massachusetts," January 14, 2009. https://www.bunkerfamilyassn.org/George_Bunker_Charlestown.pdf.

[4] "Breed’s Hill," National Park Service, accessed September 25, 2025, https://www.nps.gov/places/breeds-hill.htm.

[5] "Flags of Bunker Hill: Banners of Liberty," National Park Service, accessed September 25, 2025, https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/bh-flags.htm.

[6] Sire Thomas Hyde Page and John Montrésor, A plan of the action at Bunkers-Hill, on the 17th. of June, between His Majesty's troops under the command of Major General Howe, and the rebel forces. [1775] Map. https://www.loc.gov/item/gm71000613/.

[7] For an example, see: The Virginia gazette, (Williamsburg, VA), July 21, 1775. https://www.loc.gov/item/sn84024742/1775-07-21/ed-1/.

[8] Allen County Public Library Genealogy Center, ed., “Breed Family Association Papers,” Internet Archive, January 1, 1922, https://archive.org/details/breedfamilyassoc00bree/page/n11/mode/2up.

[9] "Breed’s Hill," National Park Service.

Sources

Allen County Public Library Genealogy Center, ed. “Breed Family Association Papers.” Internet Archive, January 1, 1922. https://archive.org/details/breedfamilyassoc00bree/page/n11/mode/2up.

"Breed’s Hill." National Park Service. Accessed September 25, 2025. https://www.nps.gov/places/breeds-hill.htm.

Brouillette, Patricia Quintero and Margaret Coffin Brown. "Bunker Hill Monument Cultural Landscape Report for Boston National Historical Park." Olmsted Center for Landscape Preservation. (National Park Service: Boston, Massachusetts, 2000), https://npshistory.com/publications/bost/clr-bunker-hill-mon.pdf.

Bunker Richards, Bette. "George Bunker of Charlestown Massachusetts." January 14, 2009. https://www.bunkerfamilyassn.org/George_Bunker_Charlestown.pdf.

“Flags of Bunker Hill: Banners of Liberty.” National Park Service. Accessed September 25, 2025. https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/bh-flags.htm.

“New Harborwalk Signs in Charlestown.” Boston Harbor Now, January 28, 2019. https://www.bostonharbornow.org/new-harborwalk-signs-in-charlestown/.

Page, Thomas Hyde, Sir, and John Montrésor. A plan of the action at Bunkers-Hill, on the 17th. of June, between His Majesty's troops under the command of Major General Howe, and the rebel forces. [1775] Map. https://www.loc.gov/item/gm71000613/.

Rosiecki, Casimer. “Fields of Deception.” National Park Service. Accessed September 25, 2025. https://www.nps.gov/articles/bunker-hill-battlefield.htm.