Last updated: January 8, 2023

Article

The Boston Anti-Man-Hunting League

Massachusetts Historical Society, Primary Research

Following the tragic rendition of Anthony Burns in 1854, the Anti-Man-Hunting League formed in Boston, with affiliates later established throughout the state. Its members included prominent activists such as Austin Bearse, Samuel Gridley Howe, Lewis Hayden, and Joshua B. Smith among others.[1] In the words of Henry Bowditch, one of the group’s founders, the league committed itself to "entrap and 'kidnap' (if you wish to use the word) the slaveholder."[2] Essentially, the Anti-Man-Hunting League pledged to use the tactics of slave catchers against them, that is, kidnap them before they could kidnap the freedom seekers that came to Massachusetts.

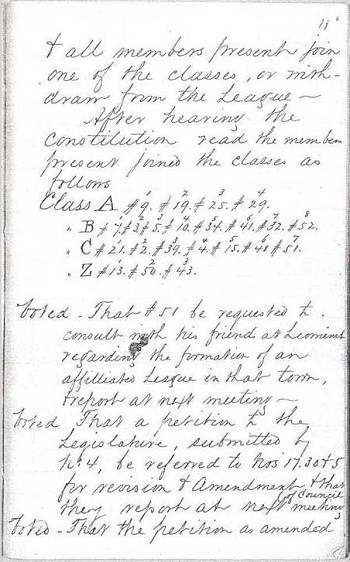

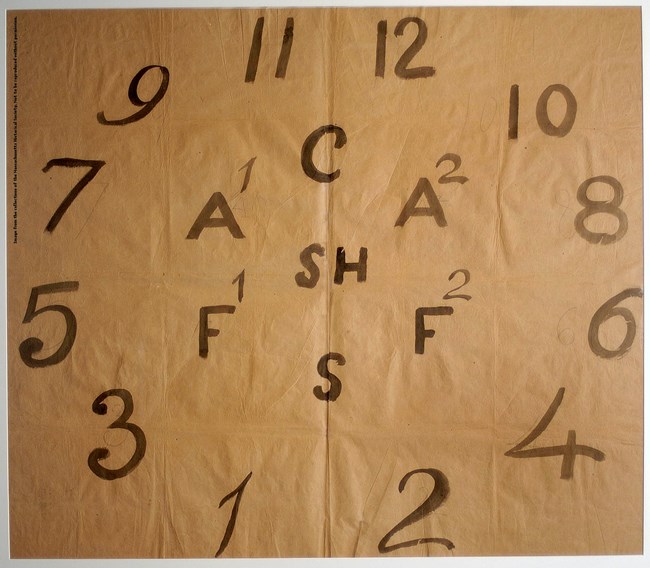

Henry Bowditch, who lived at 8 Otis Place, wrote in detail of the Anti-Man-Hunting League in letters and reminisces compiled and published by his son Vincent in 1902. In these writings, he discussed the secretive nature of the league to avoid alerting slave catchers of their numbers and tactics, as well as evading prosecution. They kept multiple and incomplete record books in coded language that the uninitiated could not decipher. Members also armed themselves. According to Bowditch, "I had kept a box of 'billies'…They had been provided for members of the league for self-defense, and made after the pattern of oak billies loaded with lead," similar to those used by law enforcement officers.[3]

Bowditch detailed the drills and tactics that the league planned and practiced regularly. For example, in one drill a member assumed the role of a slave catcher while the others accosted him, each taking a separate limb and subduing the struggling culprit.

Massachusetts Historical Society

According to Bowditch, had word of a slave catcher in town reached league members, they planned to take rooms at the hotel where the slave catcher lodged. Six members would approach the slave catcher and attempt to persuade him to either call off his pursuit or sell the enslaved freedom seeker to them. If this failed:

At a signal from the chief of the committee, his five companions were to seize the legs, arms, and head of the hunter, and rapidly carry him, without injury to him, to a carriage to be kept in readiness…he was to be driven out of town to one of our lodges, and thence transferred secretly…to other lodges…[4]

While the six members focused on the slave catcher, a larger group of league members would surround the melee and pretend to assist the slave catcher with the intention to "indirectly help the committee by keeping off all strangers or opponents."[5]

The Anti-Man-Hunting League committed itself and trained for confrontational direct action to stop slave catchers, as Bowditch said, "leaving it to others to argue before the courts or make speeches in halls."[6]

However, the Burns case, which inspired the creation of the Anti-Man-Hunting League, may have also rendered the League obsolete. The rendition of Burns, which included an unsuccessful rescue attempt, a dead slave catcher, a military takeover of Boston, and more than 50,000 people protesting in the city streets, galvanized the North against the Fugitive Slave Law. Public opinion and a stringent new Personal Liberties Law ensured that no other freedom seeker would be returned from Massachusetts. As Bowditch later reflected on the Anti-Man-Hunting League:

We fortunately never had any opportunity of trying our plan. Burns’s rendition produced so much excitement North and South that no Southerner or slave driver wished to come to Boston, for fear of something worse, perhaps, happening to him.[7]

Footnotes:

[1] Manisha Sinha, The Slave’s Cause: A History of Abolition (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2016), 538-539.

[2] Vincent Yardley Bowditch, Life and Correspondence of Henry Ingersoll Bowditch (Cambridge: Houghton, Mifflin and Co., 1902), 274.

[3] Bowditch, Life and Correspondence of Henry Ingersoll Bowditch, 280.

[4] Bowditch, Life and Correspondence of Henry Ingersoll Bowditch, 276-277.

[5] Bowditch, Life and Correspondence of Henry Ingersoll Bowditch, 276-277.

[6] Bowditch, Life and Correspondence of Henry Ingersoll Bowditch, 273.

[7] Bowditch, Life and Correspondence of Henry Ingersoll Bowditch, 280.