Last updated: January 22, 2024

Article

The Bunker Hill Monument Association: Expressing Gratitude and Patriotism

If any spot in this country should be consecrated as holy ground on which to erect the temple of liberty, that spot surely is Bunker Hill.Henry A.S. Dearborn, Board member of the Bunker Hill Monument Association and son of a Battle of Bunker Hill veteran.[1]

A group of about twenty-five Boston-area community members gathered at Boston's Exchange Coffee House in May 1823. Together, they prepared a petition to the Massachusetts legislature to establish the Bunker Hill Monument Association (BHMA). The group of men planned to raise funds to preserve the battlefield where soldiers fought during the Battle of Bunker Hill. They also wanted to build a monument commemorating this battle, one of the first battles of the American Revolution. They knew that their monument would be among the few Revolutionary War monuments in the United States at the time and it would be by far the largest.

These Bostonians joined the early 1800s trend in the US of building more Revolutionary War monuments. This trend became popular for a few reasons. Many Americans anticipated the quickly approaching 50th anniversary of the Revolutionary War, which would begin in 1825, and they viewed these events as milestones in the formation of the United States. Many veterans of the Revolutionary War were aging, and Americans wanted to honor them before they died. The monuments would recognize their sacrifices and encourage national patriotism. Long after the death of the last Revolutionary War veteran, a tradition of memorializing American soldiers from that war continues today. In 2018, New York citizens installed a monument honoring the diversity of the Colonial combatants.

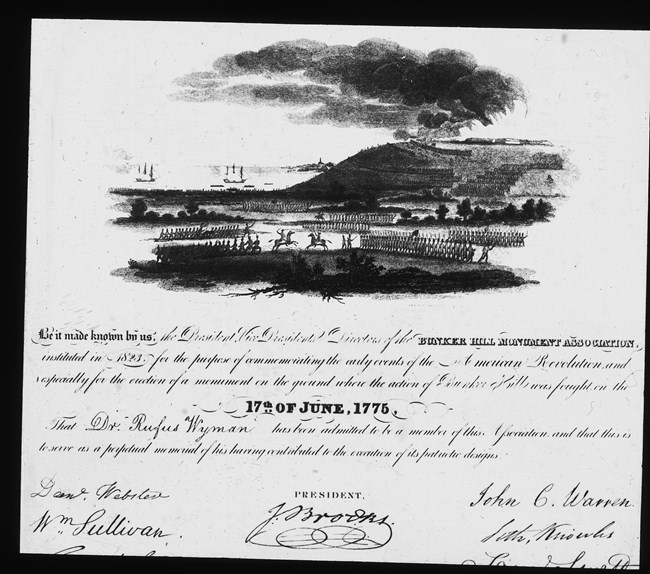

ca. 1823-1825. Charlestown Branch of the Boston Public Library.

Great Expectations

In Boston, not only did the organizers recognize the reality of the passing of veterans, but they also faced the possibility of losing the battlefield. For nearly fifty years, the Bunker Hill battlefield had remained untouched, attracting visitors to the site. In 1822, an owner of a portion of that battlefield wanted to sell the land for development, so a small group of Bostonians took action. William Tudor, a magazine publisher from a notable Boston family, met with four friends: Congressman Daniel Webster, Harvard professor Edward Everett, Merchant Thomas H. Perkins, and Doctor John C. Warren, nephew of a Battle of Bunker Hill hero. Dr. Warren immediately bought the two acres of battlefield for sale on behalf of the group.

In the following year, these five men enlisted twenty-five friends and associates with similar professions to help. This was the group that met at the Exchange Coffee House to establish the Bunker Hill Monument Association (BHMA). The men of the BHMA bought fifteen acres of the Bunker Hill battlefield in 1824. They borrowed $25,000 from a bank to pay ten individual owners for their land. Wealthier members of the BHMA provided the collateral, or guarantee, for the loan. With the land secured, they looked to fundraising efforts.

The BHMA offered membership into their Association for a minimum of $5 per person. This was a large sum, considering the average person earned about $15 a week. The BHMA expected mostly prosperous supporters to finance the monument.

The BHMA wrote letters to prominent leaders and community members across the state, country, and world, inviting them to become members of the BHMA. They sent letters to a variety of notables, from former US Presidents, such as Adams and Jefferson, to the well-known South American leader, Simón Bolívar. Not all prominent men responded positively. Caleb Stark replied to the BHMA's invitation by saying that veterans of the Revolutionary War never received their pensions, and he resented that the debt owed them "is to be paid by a stone!"[2] Son of famed Colonel John Stark, Caleb Stark served at the Battle of Bunker Hill.

Towering Figures

The BHMA used very dramatic, patriotic language in its appeal to prosperous men for donations:

"It shall be the GRANDEST MONUMENT IN THE WORLD. Such a monument will…. proclaim with grandeur the sacred duty of preserving unimpaired the FREEDOM which was purchased with PRECIOUS BLOOD."[3]

Fundraising went well and within a year the BHMA raised about $54,000 in private donations and $7000 from the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. They also received two cannons to be included in the monument. The BHMA paid off the loan for the battlefield and turned to building the monument.

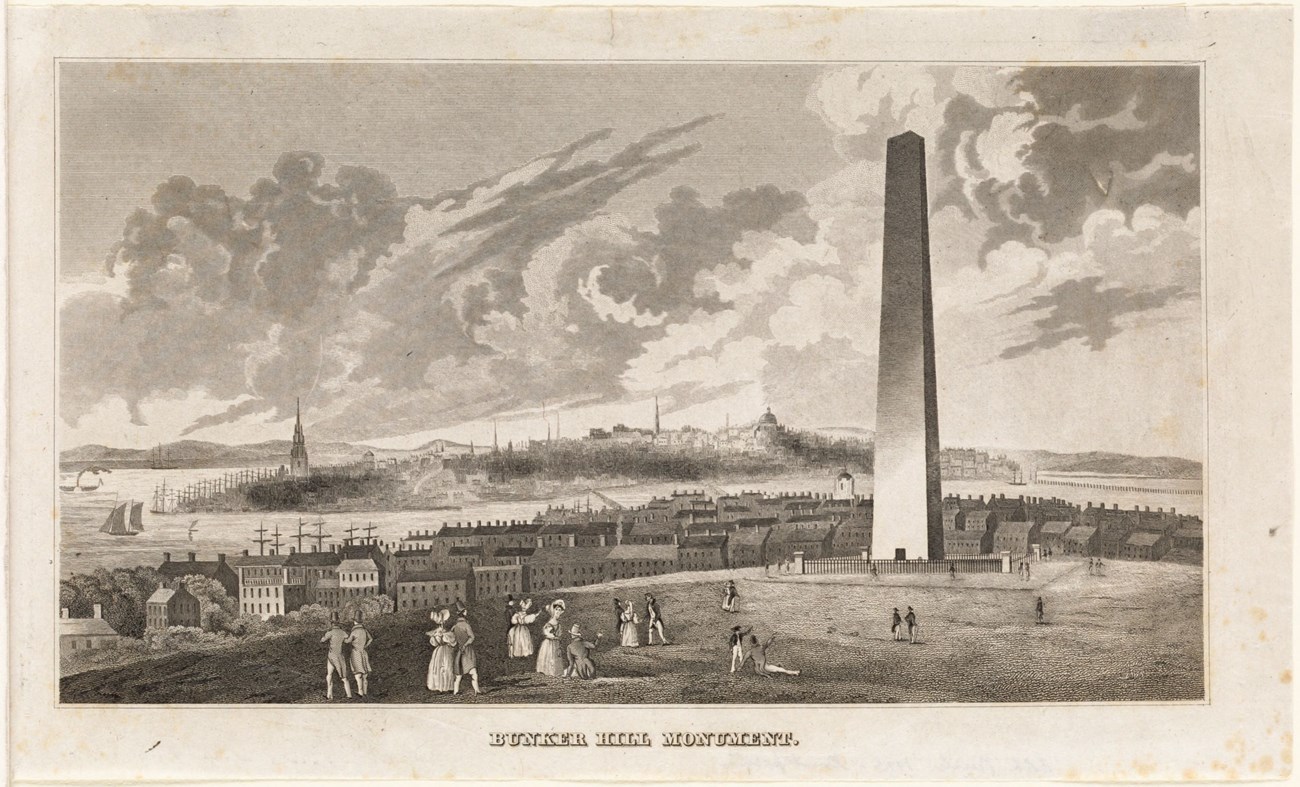

They wanted a giant granite column reaching 220 feet high. Solomon Willard, the Architect and Superintendent of the monument, estimated that it would cost $100,000 to build, or nearly $4 million today. The BHMA held a contest for the best column design, which included a $100 reward for the winner. When two contestants out of fifty suggested an obelisk, the BHMA changed course; they preferred the look of an obelisk.

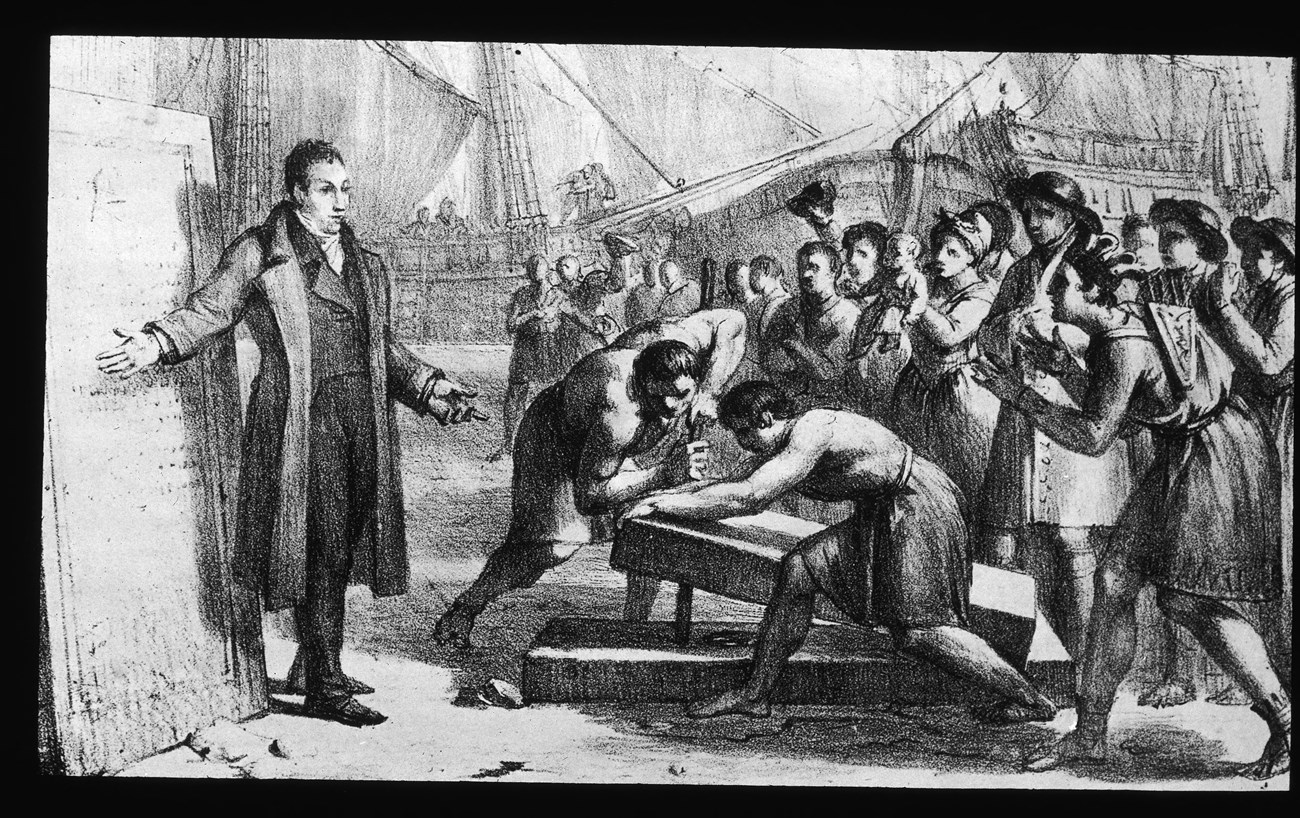

Drawn by Mlle. d' Hervilley a Paris, ca. 1825-1925, Charlestown Branch of the Boston Public Library.

At the 50th anniversary of the Battle of Bunker Hill on June 17, 1825, the BHMA held a cornerstone-laying ceremony for the monument. They invited the General Marquis de Lafayette to the event, himself a celebrated symbol of the fading Revolutionary War era. Later that year, the BHMA bought a granite quarry and in the spring of 1826, they began building the first horse-drawn commercial railway line in the US to transport the granite blocks out of the quarry.

Massachusetts Charitable Mechanic Association.

Complications arose with setting up the quarry railway, postponing the beginning of the monument's construction until 1827. Workers brought the height of the monument to 37 feet, but work stopped in less than two years when money ran out. The BHMA thought prosperous supporters would continue to make contributions, but they did not.

Meanwhile, the BHMA found three more sources of funding: women, children, and a workingmen's association. The BHMA ran a special drive aimed at women and children, accepting donations as small as 25 cents. Through this drive they collected about $3000. The Massachusetts Charitable Mechanic Association raised nearly $20,000 among its members. Five years since construction first paused, work on the monument resumed in 1834.

However, construction stopped 17 months later. At this time, the monument stood at 85 feet tall. The BHMA held no hope for more donations or loans. Hard economic times, sometimes called the Panic of 1837, hit the US economy. Work on the monument paused for another five years.

William Tudor: Courtesy of the Boston Athenaeum. Fanny Elssler: National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; gift of Monroe H. Fabian. Amos Lawrence: Massachusetts Historical Society.

ca. 1850-1898, Library of Congress.

Battlefield Won and Lost

If the BHMA wanted to finish the monument, they now had to do two things. They had to sell ten acres of the battlefield, keeping only five acres, and they had to call upon Sarah Josepha Hale. Magazine editor Sarah J. Hale had been helpful with earlier fundraising efforts among women and children. This time, Hale recommended a Ladies' Fair. Over five days, this fair raised an incredible $30,000. As a daughter of a Revolutionary War veteran, Sarah Josepha Hale supported this project out of patriotism, writing in her Ladies' Magazine: "Would not the patriot be incited to more exertions for his country, while standing on the spot where Warren fell?"[4]

According to a history of the BHMA, the money raised by Hale was crucial in finishing the monument and building it to its desired height of 220 feet. Without the Ladies' Fair, the Bunker Hill Monument might have been only about 160 feet tall. Two wealthy men, encouraged by the success of the Ladies' Fair, donated $10,000 each. Work on the monument resumed in May 1841. Workers completed the monument with a formal opening ceremony on June 17, 1843. The BHMA took over sixteen years to build the monument. It received donations from around the world, but New Englanders contributed most of the money.

Passing the Torch

The Bunker Hill Monument stands as a remarkable edifice, a testament to the work of the BHMA and its efforts to express gratitude and patriotism. The BHMA faced huge challenges in the years of construction, which they met with the help of Sarah Josepha Hale and the Massachusetts Charitable Mechanic Association. By accepting everyone's support, the BHMA created a Bunker Hill Monument relevant to more people.

Beyond constructing the monument, the BHMA added statues to the grounds of the Bunker Hill Monument to recognize heroes from the Battle of Bunker Hill: Dr. Joseph Warren (statue installed in 1857) and Colonel William Prescott (statue installed in 1881). They also built the Bunker Hill Lodge adjacent to the monument in 1903 to house the Warren statue, along with portraits of battle officers from both sides, maps, cannon balls, swords, and other weapons. Today, the portraits remain in the Lodge; other items are now in the Bunker Hill Museum across the street from the Monument.

"Bunker Hill Monument." ca. 1825-1857. Boston Public Library.

The BHMA built and managed the Bunker Hill Monument for nearly 100 years. Over the years, the BHMA had hundreds of members, but a much smaller Board of Directors ran the Association. For generations, many Boston families had multiple members serve on the Board of Directors.

Since its completion, visitors have come to visit the impressive Monument. Initially, visitors could climb the Monument for a small fee. However, over the years the BHMA realized these fees did not cover the expense of maintaining the monument and grounds. In 1919, the BHMA transferred the monument to the Commonwealth of Massachusetts.

The National Parks of Boston, part of the National Park Service, is the current caretaker of the Bunker Hill Monument. The Commonwealth of Massachusetts transferred the monument to the National Park Service in 1975. The Bunker Hill Monument Association is still an active organization and conducts a patriotic ceremony every June 17 on the grounds of the Monument.

Footnotes

[1] George W. Warren, The History of the Bunker Hill Monument Association During the First Century of the US (Boston, MA: James R Osgood and Co., 1877), 235.

[2] George W. Warren, 65.

[3] George W. Warren, 87.

[4] George W. Warren, 293.

Sources

Buckingham, Joseph T. "Fanny Elssler at Boston." Boston Courier in the National Intelligencer. October 5, 1840. https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/GT3017649590/NCNP?u=mlin_b_bpublic&sid=bookmark-NCNP&xid=2e26e319.

O'Keefe, Kieran J. "Monuments to the American Revolution." Journal of the American Revolution (September 2019). https://allthingsliberty.com/2019/09/monuments-to-the-american-revolution/.

"Prices and Wages by Decade: 1830-1839." Libraries University of Missouri. Accessed March 2023. https://libraryguides.missouri.edu/pricesandwages/1830-1839.

Purcell, Sarah J. Sealed with Blood: War, Sacrifice and Memory in Revolutionary America. University of Pennsylvania Press: March 25, 2010.

Wheildon, William W. Memoir of Solomon Willard, Architect and Superintendent of the Bunker Hill Monument. Boston, MA: Printed by Direction of the Monument Association, 1865.