Last updated: January 22, 2025

Article

The DESIRE and the Beginnings of the Massachusetts Slave Trade

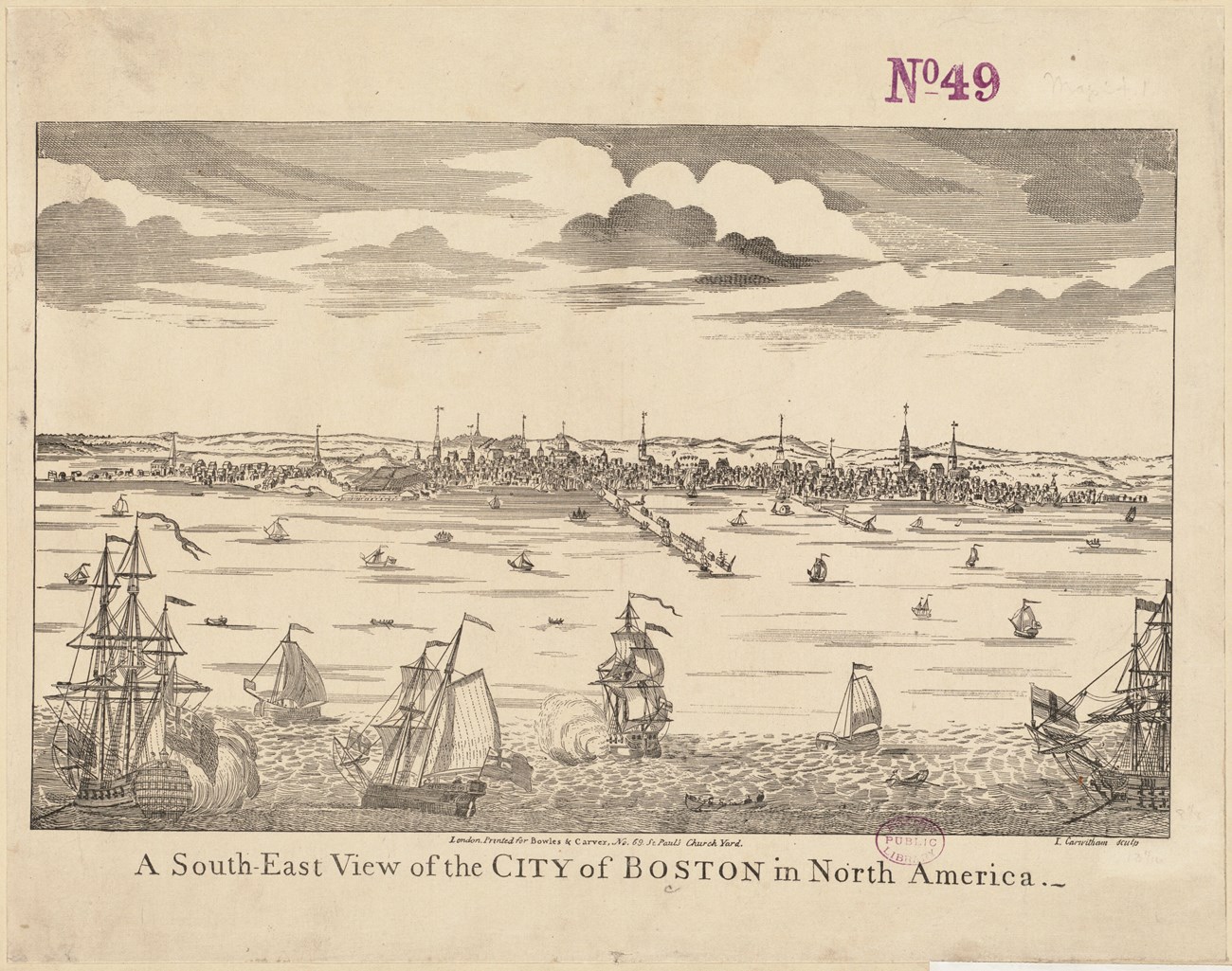

Thomas Carwitham, Boston Public Library.

In a July 13, 1637 journal entry, in the midst of the Pequot War, Governor John Winthrop of the Massachusetts Bay Colony wrote of sending captive Pequots to the West Indies to be sold into slavery:

We sent fifteen of the boys and two women to Bermuda, by Mr. Peirce; but he, missing it, carried them to Providence Isle.[1]

On February 26, 1638, Winthrop recorded in his journal that:

Mr. Peirce, in the Salem ship, the Desire, returned from the West Indies after seven months. He had been at Providence, and brought some cotton, and tobacco, and negroes, etc. from thence, and salt from Tertugos.[2]

These two stark journal entries capturing the departure and return of the Desire serve as the first documented instances of Massachusetts’s long history with the slave trade.

Though Winthrop did not specify where the Desire landed, the ship most likely arrived in Boston in the area then known as Town Cove, and later as Bendall’s Cove and the Town Dock. A hundred and four years later, Faneuil Hall opened its doors in this general area.[3]

For the next 150 years, Boston and Massachusetts served as a major center of the slave trade and port of entry for enslaved people of African descent. Historian Lorenzo Greene wrote:

In short, the New England slave trade of the seventeenth century seems to have been centered almost wholly in Massachusetts, with Boston the chief, if not the only, slave port.[4]

Records uncovered thus far indicate nearly 200 voyages either to or from Boston involved in the slave trade.[5] These include Trans-Atlantic voyages to and from Africa, as well as the Intra-American slave trade between Boston and the West Indies.[6]

Massachusetts, and Boston, in particular, benefitted from the Trans-Atlantic trade economy, which included the trafficking of enslaved peoples as well as trading goods consumed and produced by enslaved people. Leading families of Boston including the Faneuils built their own trading empires within this economy. This economic system provided employment to numerous Bostonians and Massachusetts residents. For example, by 1763, at the dawn of the American Revolution, the Massachusetts slave trade employed about "five thousand sailors in addition to the numerous coopers, tanners, and sailmakers who serviced the ships."[7]

Though the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court declared slavery "incompatable" with the new state constitution in 1783, the slave trade continued in the years that followed. In a 1788 petition to the General Court of Massachusetts, Black activist Prince Hall captured the horror and hypocrisy of this practice in a place renowned for its deep Puritan roots and love of liberty. He wrote:

your petitioners have for some time past, beheld with grief, ships cleared out from this harbor for Africa, and they either steal our brothers and sisters, fill their ship-holds full of unhappy men and women, crowded together, then set out for the best market to sell them there, like sheep for slaughter, and then return here like honest men, after having sported with the lives and liberty of their fellow-men, and at the same time call themselves Christians. Blush, O Heavens, at this![8]

Though the federal "Act Prohibiting the Importation of Slaves" went into effect in 1808, many traders, including some from Boston, continued to illegally traffick enslaved Africans well into the 1800s.[9]

Footnotes:

[1] John Winthrop, Winthrop’s Journal, History of New England, 1630-1649 (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1908), 228.

[2] Winthrop, 260

[3] Rob Heinrich, "The Desire and the Beginnings of Slavery in Boston," (Boston National Historical Park, 2014).

[4] Lorenzo Greene, The Negro in Colonial New England, 1620-1776 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1942), 22.

[5] Middle Passage Port Marker, Long Wharf, Boston.

[6] Middle Passage Port Marker, Long Wharf, Boston.

[7] Edgar J. McManus, Black Bondage in the North (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 1973), 10.

[8] Prince Hall, "To the Honorable the Senate and House of Representatives of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, in General Court assembled, on the 27th February, 1788," accessed June 5, 2024.

[9] Equal Justice Initiative, "The Transatlantic Slave Trade, Chapter 3: Boston, Massachusetts," accessed June 5, 2024.