Last updated: December 3, 2024

Article

50 Nifty Finds #39: An NPS Art Factory

Following the success of the first National Park Service (NPS) poster series, the NPS Western Museum Laboratories (WML) created a new series of now-iconic posters between 1938 and 1941. Usually described as “the WPA park posters,” they should rightfully be called “the WML posters.” Artists and printers funded through several New Deal programs worked at the WML to create silkscreened posters publicizing specific national parks and educating visitors. New research reveals that there were more designs than previously thought (including several previously unknown ones), reevaluates what is known about the artists behind them, and argues that modern reproductions have made the designs more popular—and more significant to NPS graphic identity—than they were in the 1930s and 1940s.

Mechanizing Art

In 1936 the centuries-old silkscreen printing process was refined for mass production. The result was a mechanical process for producing multi-colored posters that was faster and cheaper than hand painting. These methods for creating silkscreen prints, also called serigraphs, were quickly embraced by artists throughout the United States.

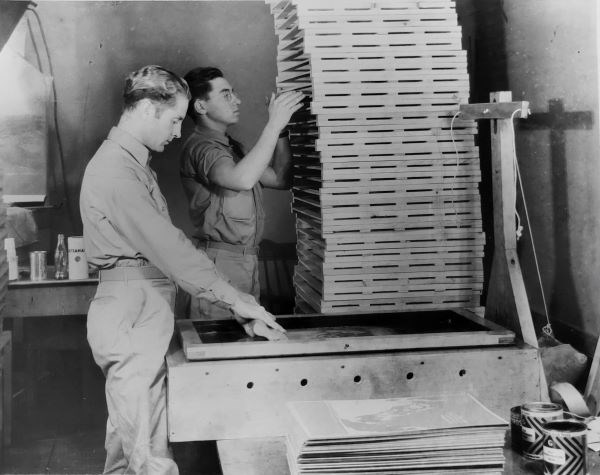

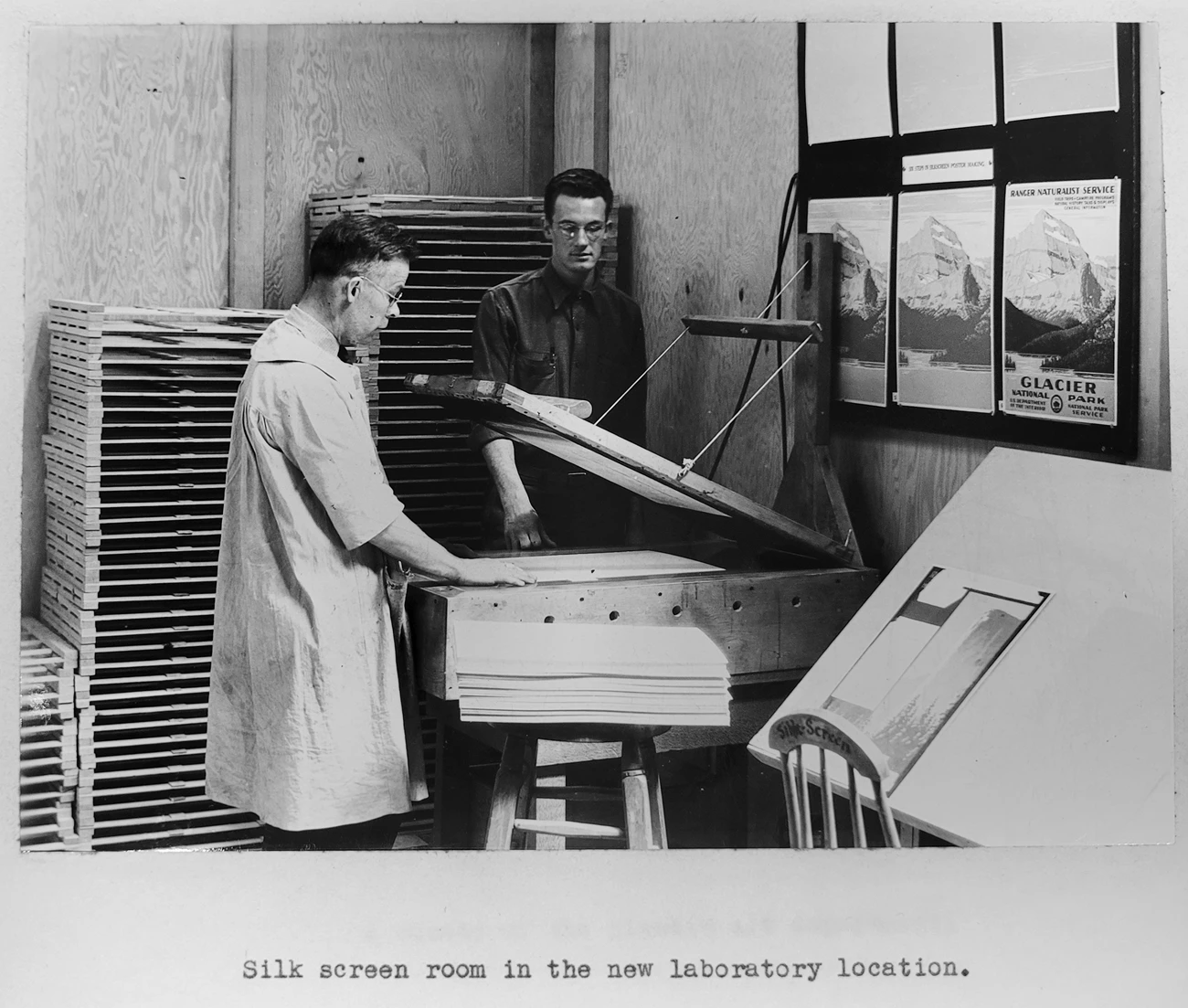

The silkscreen printing techniques of the time are described in Silk Screen Stenciling as Fine Art (1942). The basic equipment needed is a flat wooden table or base, a wooden frame hinged to the base along the top edge, screen fabric, a thick rubber squeegee, stencils of the design, glue or lacquer, brushes, process oil colors (paints), thinners, white cardstock, and drying racks. In practice, the frame serves as a stretcher for the screen fabric and as a basin to hold the paint. The stencils mask areas where paint is not wanted, and multiple stencils allow different colors to be applied. The squeegee pushes the paint through the fabric in the frame. The first color is applied to all cards to be printed. If the number of prints being made is large enough, the paint will be dry when it is time to start the next color. The number of cards that fit on each shelf of the rack depends on the size of the poster.

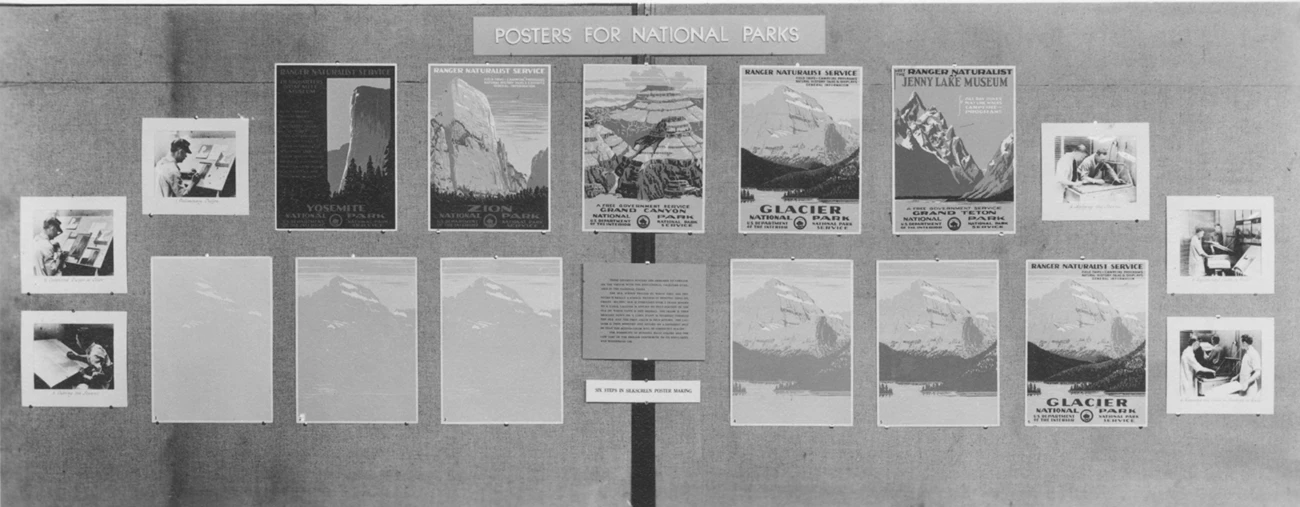

The WML described its own process in a July 1939 exhibit in Washington, DC.

These colorful posters are designed to familiarize visitors with the educational facilities available in national parks. The silk screen process by which they are produced is really a stencil method of printing using oil paints. Bolting silk is stretched over a frame hinged to a table. Lacquer is applied to that portion of the silk on which paint is not desired. The frame is then brought down on a card. Paint is squeezed through the silk, and the first color is thus applied. The lacquer is then removed and applied on a different spot so that the second color will be correctly placed. The possibility of running many colors and the low cost of the process contribute to its popularity and widespread use.

Six photographs of the WML staff working on the poster series are part of the exhibit. The captions define the basic process as 1) preliminary design; 2) completed design in color; 3) cutting the stencil; 4) applying the stencil; 5) registering the card in the press; and 6) running the color and stacking in the rack.

The Second NPS Poster Series

From 1925 to 1937, the NPS Field Division of Education created exhibits and other products for park museums. Metalworking and carpentry shops, a library, artist studios, and darkrooms, located in several buildings on land owned by the University of California, Berkeley, supported the division’s work for national parks west of the Mississippi River.

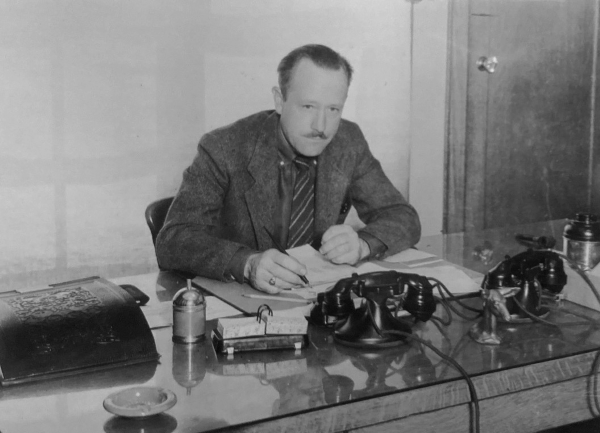

In April 1937 the Field Division of Education became the WML, under the direction of Dorr G. Yeager, who was also assistant chief of the NPS Museum Division. Ongoing New Deal programs implemented during the Great Depression allowed the WML to acquire skilled craftspeople, artists, and others with funding from the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), Works Progress Administration (WPA), and National Youth Administration (NYA).

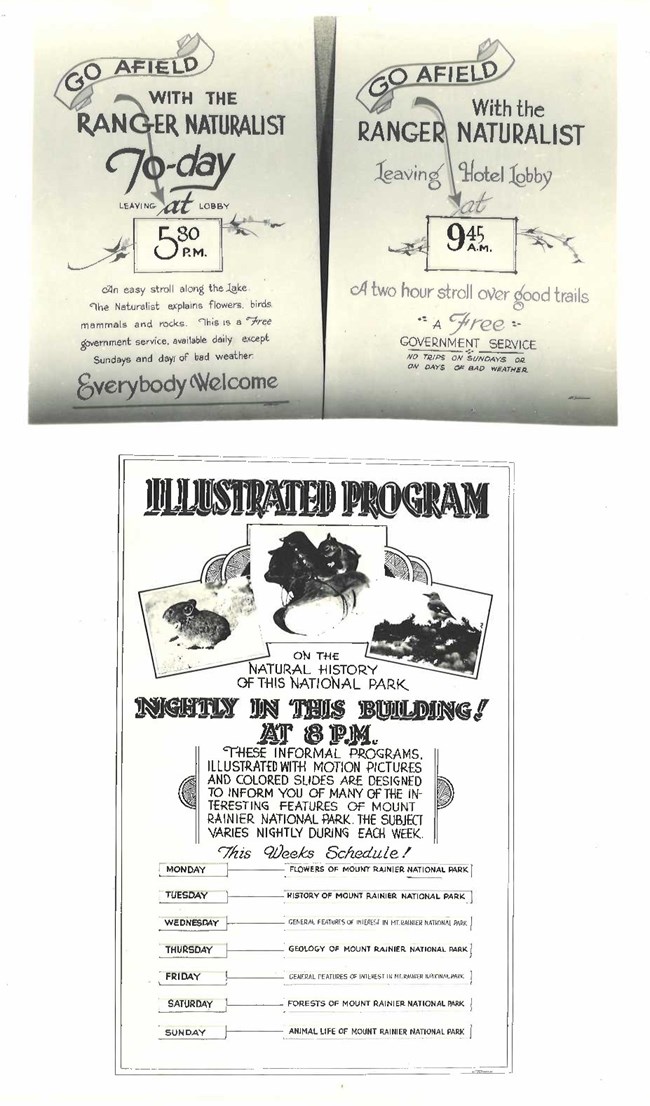

The WML established a formal poster program in spring 1938. Debuted in the April 1938 Miscellaneous Products Available to National Parks and Monuments from the Western Museum Laboratories, the posters were more informational than inspirational. The catalog notes,

Several of the parks have requested us to prepare posters and signs. These can be made up in any style desired. A type which has proven popular is that used in announcing hikes or lectures. Slots are so devised that the dates and the subject of the talk can be inserted. (Supplied free of charge to the parks).

On August 26, 1938, Yeager wrote to Frank Pinkley, superintendent of the Southwestern National Monuments (SWNM), describing the need for a new process.

Since issuing the publication “Miscellaneous Products of the Western Museum Laboratories,” we have hardly been able to keep up with the requests from parks for the various items. This applies especially to the posters advertising lakes, hikes, and so forth. We soon found that it would be absolutely impossible to fill the orders from the parks for these posters if they were handmade and lettered. We have therefore put in a silk screen process, especially for colored posters, by which we can turn them out in large quantities.

Yeager went on to note that “During the coming winter we plan to make up individual posters for each of the parks desiring them. Posters will of course be characteristic of the parks for which they are made.”

In January 1939 the WML distributed its second edition of Miscellaneous Products Available to National Parks and Monuments from the Western Museum Laboratories. The catalog outlines many of the products and services available as a direct result of emergency relief funding. The WML employees supplied the items for the cost of delivery or, in some cases, the cost of materials and delivery.

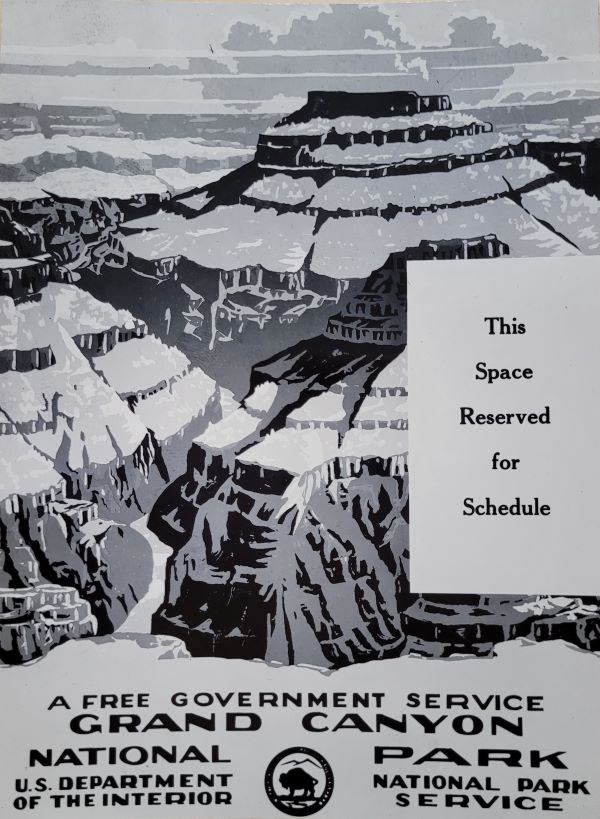

The catalog also featured the new silkscreen park posters Yeager promised. An example of the design for Grand Canyon National Park was included. Of note is that the poster includes a white rectangular area that reads “This Space Reserved for Schedule.” This was an area where parks could add lectures, hikes, and other services offered in the park at specific times and places.

A Team Effort

Screen printing is often a collaborative effort between several artists who each play a role in creating designs, selecting colors, cutting stencils, and printing. The identities and roles of everyone involved in creating the WML park posters are unknown. Without a doubt, each poster would have taken a team of artists and technicians to complete. The WPA and CCC artists behind the many WML posters would have varied over time as new projects began, as assignments changed, and particularly as World War II approached and the number of workers at the WML declined.

Lorenzo Moffett, a CCC-funded museum preparatory artist, managed the WML Art Department, which included the silkscreen printing program. It’s possible he had a more direct role in designing the posters produced in 1938 and early 1939, but he was better known for sculptures than paintings. The 1939 Miscellaneous Products catalog stated,

Study sketches should be sent to us from any area desiring to order silk screen posters. Such sketches should contain desired text which should be held to a minimum. These laboratories will then work out color schemes for the sketches and submit to the park before work begins.

This may have turned out to be impractical when parks lacked artistic staff because several of the WML’s monthly reports refer to creating study sketches. Park staff were involved in at least reviewing the proposed designs. Unfortunately, the reports don’t mention the names of those at WML doing the work, referencing only “man hours” charged to the WPA, CCC, and NYA programs. Families often know some of the history institutions have forgotten, and three names were mentioned in correspondence from the artists’ families in the 1990s: Elmer Duffield, Dale Miller, and Chester Don Powell.

In addition, the letters “EM” are in the border of the stylized DOI seal at the bottom of the two posters for Yellowstone National Park. If the letters are a person’s initials, their identity remains a mystery. The Lassen Volcanic National Park poster has the letters “DM” in the seal’s border. There are no complete signatures on the final WML park posters, although evidence suggests that at least one unidentified rough sketch was signed by Powell. It’s not clear if he signed it as the artist or as the person with the authority to approve the design. The man shown cutting a silkscreen stencil in the 1939 National Park Service Posters exhibit (step 3) remains unidentified.

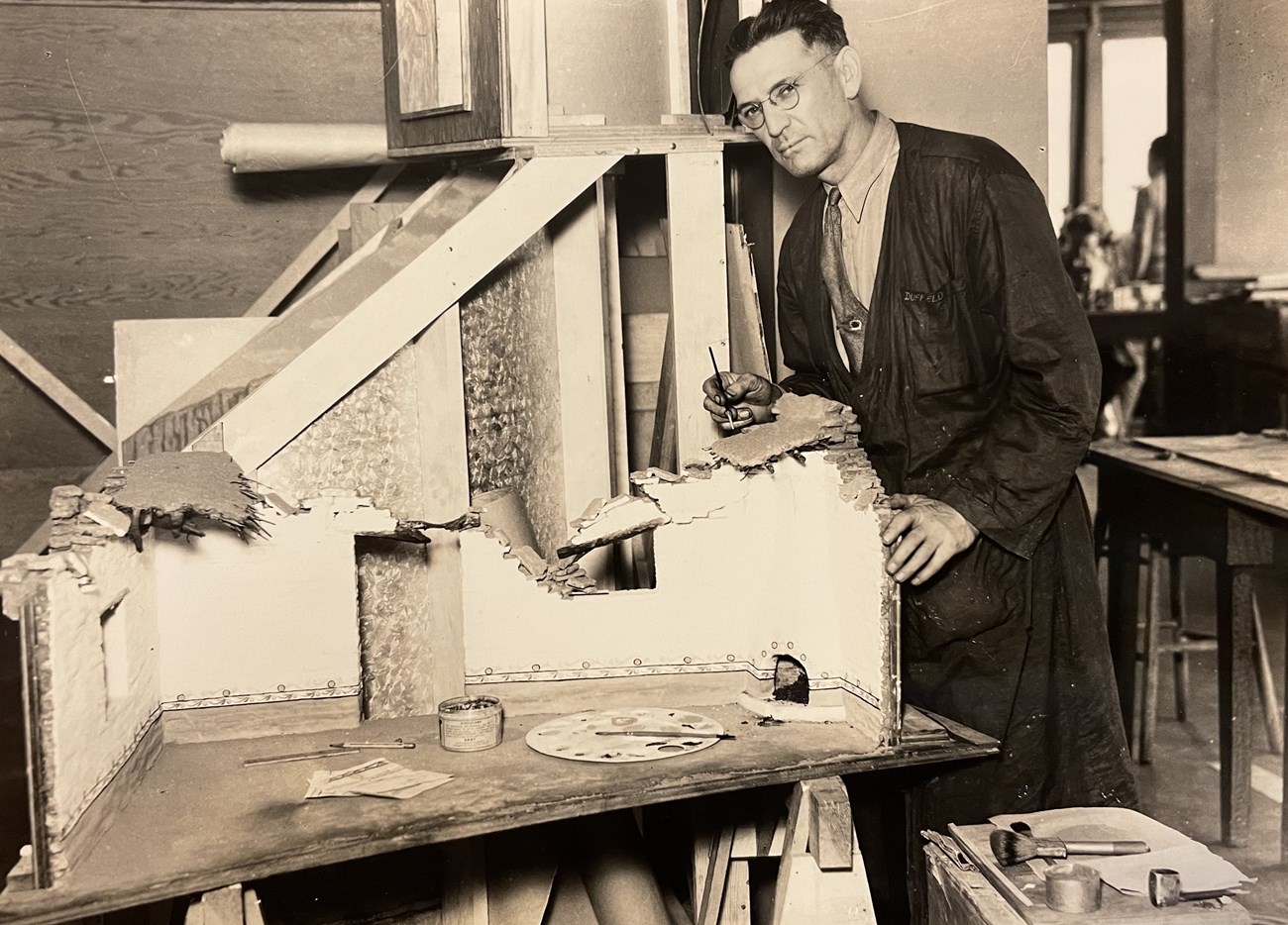

Elmer Duffield

Elmer Raymond Duffield was born August 14, 1892, in Horace, Kansas. At 17 he was an assistant secretary at the YMCA in Tribune, Kansas. In 1915 he married Minnie. Within two years, they had two sons, and the family had moved to Colorado. After working briefly as a farm laborer, Duffield was hired in 1918 as a steelworker in Pueblo. He worked in that industry until at least 1930.

The family moved to California in the early 1930s. He was working at the WML by at least 1936 when he and C. Don Powell worked on park dioramas and models, including for Glacier and Tumacácori. Powell’s son Richard recalled in 1998 that Duffield worked with his father “on some jobs, as to which I do not know.” Their diorama work together is well documented by photographs in the NPS History Collection. Perhaps the best evidence that he worked on the park poster series comes from the 1940 US census that lists Duffield’s occupation as an NPS printer. That is hardly conclusive, however, given that the WML printed many other types of materials. Duffield left WML around 1941. It’s not clear if, like many other staff, he left for a job in the defense industry or if he stayed until the WML’s WPA project ended in July 1941.

By 1942 he was working in the construction industry. It doesn’t appear that Duffield fought in WWII. In 1944 his occupation was listed as artist. The 1950 census notes that he was working as a carpenter. He became a member of the Pile Drivers and Bridge Builders Union in San Francisco, suggesting a career outside of the arts for the remainder of his life. Elmer Duffield died on March 23, 1973, in Concord, California.

Dale Miller

Dale Allen Miller was born on February 3, 1917, in Cleveland, Ohio. He moved to California with his family when he was a child. He attended Castlemont High School in Oakland, California. While there he received his first comprehensive art training. His teacher, William Rice, sponsored his studies at the California College of Arts and Crafts.

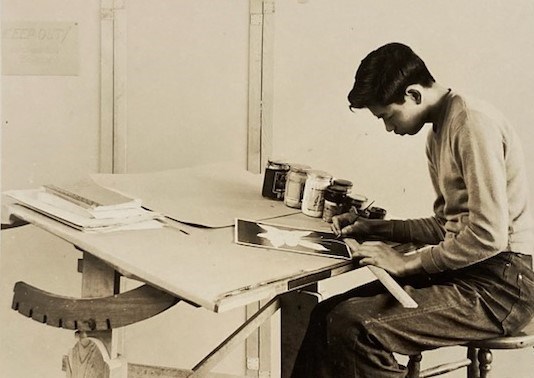

Miller worked for the WML in the late 1930s and was certainly involved in the park poster project. Traditionally credited as the printer of the posters, it’s interesting to note that photographs in the 1939 exhibit show Powell operating the press, not Miller. Powell’s son, Richard, later recalled, “One student whom my dad was proud of was Dale Miller who later went on doing this and other art and design work.” It’s conceivable then that Don Powell was training Miller in spring 1939. Miller may have graduated to running the press himself, but that cannot be confirmed.

Miller was an artist in his own right. It’s possible that the “DM” in the stylized DOI seal in the Lassen Volcanic National Park poster refers to him, suggesting that he may have designed at least one poster—or, as part of his training, was responsible for completing the design in color (from the preliminary design) and added his initials. It seems unlikely that they would have been added during the printing process. A photograph in the NPS History Collection offers another tantalizing connection between Miller and the WML's work for Lassen Volcanic National Park. Although the focus of the image are the men and women working on the Lassen Peak eruption diorama, Miller can be seen in the far right of the photo. It’s conceivable then that he was involved in both the diorama and poster creation.

Few specifics are known about Miller’s life during and after WWII. About 1942 Miller married Marjorie Parker. They went on to have two sons. The 1950 US census records that Miller was working as a “graphic arts mechanic” at a silkscreen printing company. He continued creating his own paintings as well. Watercolor was his favorite medium. His art can be found in many private, corporate, and international collections. Dale Allen Miller died on December 5, 2005.

C. Don Powell

Chester Don Powell, often referred to as C. Don Powell or Don Powell, may have been one of the artists behind some of the WML posters. Assertions that he was probably the principal designer behind the series have not been confirmed. Indeed the evidence indicates that he could not have been involved in at least seven of them, including creation of the first three posters in the series.

Powell was born on February 18, 1896, in Westmoreland, Kansas. He was one of six children born to Charles D. Powell and Charlotte D. Sherman. As a young man Powell was part of the family hardware and farm supply business, working as a plumber by 1917 and a salesman by 1920. The family moved to Kansas City, Missouri, when a poor economy forced them to close the business.

According to his son Richard Powell, Don Powell first attended art school in Kansas City before moving to Chicago for art school. WPA papers at the Archives of American Art don’t mention an art school but note six years of training in commercial art and mural production, perhaps suggesting an apprenticeship rather than an academic program. Richard Powell recalled that his father’s corporate clients in Chicago included the Meyercord Company, Lipton Tea, and the Wurlitzer Organ Company, among others.

Powell married Selma Hanson in Chicago on December 20, 1927. The couple took a delayed honeymoon in San Francisco. They enjoyed the city, decided to stay, and sold their return train tickets. Powell had an office as a commercial artist in the Montgomery Street District of San Francisco. His clients included the Shell Oil Company, Golden State Milk, and Sunset Press, among others. The Powells’ three children—Richard, Shirley, and Patricia—were born in California.

The financial collapse in 1929 left Powell unemployed. The 1930 US census records that he was an artist working “on his own account.” He eventually got a job as a flagman on road crews. It's been suggested that this work was funded by the Public Works Administration (PWA). However, that position isn't mentioned in his official personnel file. Instead, there is a laborer position with the Civil Works Administration (CWA) which is likely that job. The CWA was a short-term temporary program to provide jobs during the hard winter of 1933–1934. It ended on March 31, 1934. Powell's part-time CWA job ended March 29.

Later in 1934 Powell worked as an artist under the State Emergency Relief Agency (SERA) program. He and other artists worked collaboratively on murals in the Oakland Auditorium Theater because the SERA funds limited each to 25 or 75 hours per month. On November 14, 1935, Powell was assigned to WPA project 1256 in Berkeley. Although the specifics of that project are unknown, it seems likely that it was related to roadwork as the project supervisor, J. Kreitler, went on to become Berkeley's supervisor of roads after WWII.

Powell got work as an artist with the Federal Art Project (FAP) in Oakland on January 8, 1936. He worked under Willis Foster at the Lakeview Annex, a WPA center for art, music, and visual aid projects. He held several titles during his work at the annex, including artist, artist professional, and sculptor. Photographs in the NPS History Collection show that Powell worked on dioramas for Tumacácori National Monument and Zion and Glacier national parks in late 1936 and 1937. He also prepared a drawing for Devils Tower National Monument during this period. Although the relationship between the WML and the FAp project at the Lakeview Annex is unclear, Powell's projects are evidence that one existed.

His personnel file indicates that he worked for the WML at its Fulton Street address in Berkeley beginning July 16, 1937, when he was assigned to the "Museum Project." His senior artist position was approved for 78 hours at $1.21 per hour. The Museum Project hired carpenters, various craftsmen, and support staff who built cases, worked on exhibit elements, and produced most of the miscellaneous projects that the WML offered to parks. Beginning in 1938 that would have included the park posters. His next appointment, begun on August 30, 1937, was as a senior craftsman for 90 hours at $1.04 per hour. He received a notice of termination, however, on September 21, 1937, for refusing private employment.

Despite this, he was issued another notice to report for work on September 29, 1937, as a senior craftsman (artist) at the WML to prepare museum exhibits. It seems possible that his job title was regularly changed to keep him on the rolls. On July 6, 1938, he was assigned to the Museum Project as a research associate (artist) for 108 hours, earning just $0.87 per hour. Photographs in the NPS History Collection, however, document that from at least May 1938 until December that year, he worked on a pueblo diorama for Zion National Park. It seems reasonable to assume, therefore, that his personnel records are incomplete, although the individual earnings record in the file appear to be more accurate than the notices to report.

Regarding the WML, Powell's son Richard wrote in 1998, “I recollect visiting there when I was a boy. They were working on dioramas, models, and silk-screening.” The silk screening reference dates this recollection to 1938 or later. Powell was working as a research associate (artist) at the WML facility in Emeryville when he was terminated effective August 15, 1939, because of the policy prohibiting continuous employment for more than 18 months.

Effective November 6, 1939, Powell was assigned 130 hours to work as a commercial artist for the US Forest Service study of California forests. He drew a lodgepole needle miner moth, endemic to Yosemite National Park, as part of that project. On November 24, 1939, he was assigned as an adult education teacher at McKinley School in Berkeley. Although that appointment was also limited to 130 hours, he didn't receive a notice of termination until May 6, 1941, suggesting he taught for a longer period of time.

Despite his termination, he was once again employed by the WPA on September 3, 1941. This time he was hired as a senior colorist at 421 Broadway in Oakland. It's not clear if that position was with the NPS or what it entailed, although that may refer to hand coloring lantern slides (something which was commonly done at the WML). He was terminated from that position on September 19, 1941.

By January 1942 he was receiving training in marine drafting, also through the WPA. The last pay stub for this position in his personnel file at the National Archives notes his last day worked as March 31, 1942. It also notes that he had private employment at that time, which may have been a job as a modeler at Kaiser Shipyards in Richmond, California, a position he is known to have held. His 1942 draft registration form lists his employer as Richmond Shipbuilding #3.

After the war, Powell worked for Preston Models of San Francisco and Able Engineering Company. He developed an architectural career, designing houses, churches, schools, banks, and other buildings. During his career he also did pen and ink drawings for journal and catalog illustrations, designed candy boxes, and drew patent designs. The 1950 US census lists his occupation as an artist in the television industry. Although it’s not clear all that entailed, Powell did a chalk drawing on the first live religious television show in San Francisco.

About 1955 Powell got an art and design job with the Sixth Army Engineers at the Presidio in San Francisco. He worked there until about 10 weeks before he died, age 68, on September 5, 1964, in Hayward, California.

A Set Up?

Richard Powell recalled in 1998, “My dad worked on the silk-screen posters of the various national parks. They did production on these. [I] recollect the drying racks.” This description is interesting because it speaks of poster production, not design. Most photographs of Powell found to date show him working on dioramas or at the silkscreen press. The two images of Powell at the drafting table in the 1939 National Park Posters exhibit are the basis of the belief that Powell was the artist for most of the park posters. Given the poster design timeline, however, it’s possible that the photos were staged for use in the exhibit.

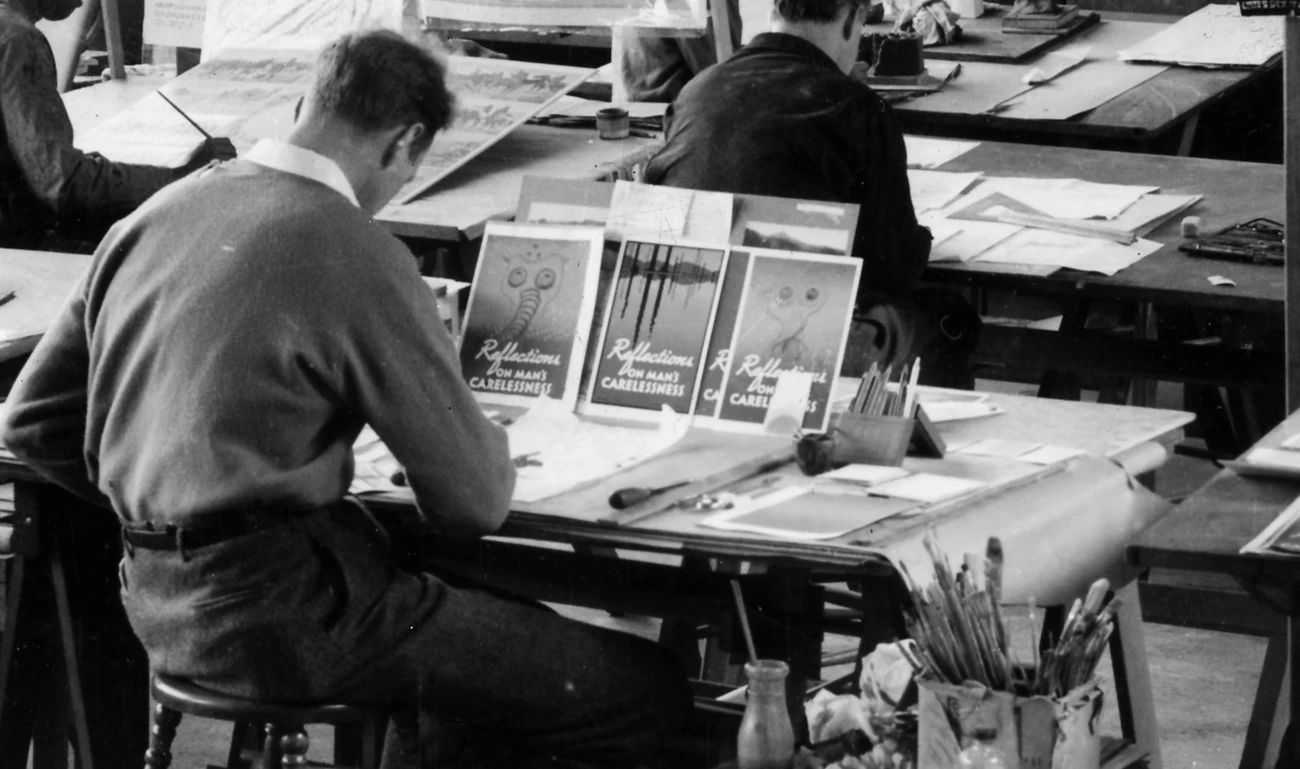

In the first photo (step 1), Powell has three small preliminary designs on the drafting table in front of him, as if he were working on all three at once. Together they represent an initial design (Old Faithful), a more advanced design (Yosemite), and a completed one (Yellowstone Falls). In the second photo (step 2), the larger Yosemite poster has been added. Powell appears to be actively working on it, but the design of the preliminary poster doesn't completely match that of the larger one. The black marks seen on the drafting table are identical, suggesting that the photos were taken in quick succession, rather than over time as work progressed. Most significantly, although the Yosemite and Yellowstone Falls posters were completed in April 1939, the Old Faithful study sketches weren't started until June. The photograph of the National Park Posters exhibit was taken on June 23, 1939, before the exhibit was sent to Washington, DC, for installation. It seems highly likely that the Old Faithful poster was in progress at the time, and the examples of other posters were brought in to show other stages of design for the exhibit.

Of course, a staged photo doesn't mean that Powell was the printer and not a designer. As noted above, Miller may have also done both jobs. However, if Powell didn't design them, it would go a long way towards explaining the apparent discrepancy for both Yellowstone posters. They have been attributed to Powell but the letters "EM" (believed to be the designer's initials) are in the borders around the DOI seals.

The new information from Powell's personnel file certainly clarifies which posters he could not have been involved with. When the Grand Teton, Grand Canyon, and Wind Cave posters were being made in August, November, and December 1938, respectively, Powell was working on dioramas, and it is unlikely that he was also working on the posters. Because he was terminated on August 15, 1939, it is also possible to completely rule out posters he could not have worked on: Great Smoky Mountains, Petrified Forest, Bandelier, and Rocky Mountain. Although its unlikely he completed the other posters, the timing means that it is technically possible that he was part of the preliminary design process for the posters or printed some of them for Glacier, Zion, Yellowstone Falls, Yosemite, Fort Marion, Saguaro, Lassen Volcanic, Yellowstone Old Faithful, and Mount Rainier.

The Yellowstone Old Faithful poster is most frequently attributed to him because it is the one that he had in his private collection (before it was donated to the NPS History Collection). Study sketches for this poster were made in June 1939, and so it is possible that Powell was the artist for those drawings. However, printing of the posters didn't happen until September and October 1939, after Powell left the WML.

In 1999 Richard Powell wrote, "Obviously there is no proof positive my dad did all of them, but in several of the pictures you can see him working with one or more." Although we now believe that those photographs were staged for the 1939 exhibit, Powell undoubtedly played many roles—model maker, artist, printer, colleague, and mentor—during his time at the WML.

The WML Posters

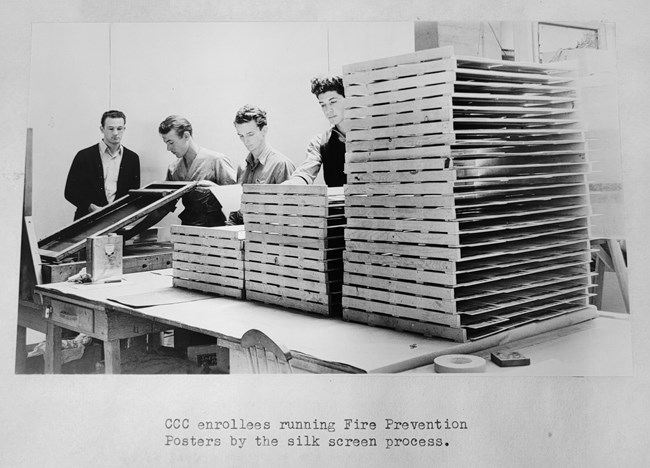

Although the park posters are frequently referred to as “the WPA posters,” it’s more accurate to call them “the WML posters.” The historical record clearly notes that the posters were a WML initiative at the request of NPS staff. The WML used labor from the WPA, CCC, and NYA to accomplish different aspects of the poster project over time. While it’s perhaps tempting to associate the art with the WPA and the fabrication with the CCC and NYA, “CCC boys” at WML also worked in the art department. As shown below, one photo from about 1941 shows an unknown CCC enrollee designing a flower poster for silkscreen printing.

Although what appear to be initials are seen on a few posters, the designers didn’t sign their work. Without further information, the only thing that can be said with certainty is that they were produced by the WML. Park posters for Petrified Forest National Monument (now Petrified Forest National Park), Mount Rainier and Great Smoky Mountains national parks, and Bandelier National Monument include both WPA and CCC on the front of each poster, as do other surviving posters with different themes. Richard Powell also noted that the park poster project was done “in cooperation with the CCC.”

Others have suggested that the Department of Interior (DOI) seal on the posters was modified because WPA artists didn’t have the authority to use it. That seems unlikely given that these posters were produced by an NPS program, not an unaffiliated Federal Arts Program (FAP) project. It seems more plausible that the level of detail needed to faithfully reproduce the DOI seal couldn’t be achieved with their stencils.

The Park Poster Series

For decades researchers believed that the WML park poster series consisted of 14 designs for 13 parks. Negatives and prints made on May 5, 1940, and found in the NPS History Collection document posters for Grand Teton, Grand Canyon, Yosemite, Glacier, Yellowstone (2 designs), Great Smoky Mountains, Lassen Volcanic, Wind Cave, Zion, and Mount Rainier national parks and Petrified Forest and Fort Marion national monuments. Surviving posters for Bandelier National Monument provided proof positive that it was created after the 1940 photographs were taken.

New research in the WML monthly reports at the NPS History Collection has uncovered one or perhaps two additional park posters—and Rocky Mountain National Park and Saguaro National Monument (now a national park)—bringing the total to 15 or 16. That number is still too low, however, as many (or perhaps even most) park posters were printed with and without white blocks where parks could list or attach a schedule of visitor programs. Posters with these schedule blocks represent an overlooked second design for the parks. Evidence shows that the schedule block design was made for at least the Grand Teton, Grand Canyon, and Great Smoky Mountains posters. Although one might argue that it was an option for early posters that faded away, a photograph of the Great Smoky Mountains poster documents that it was still in use in 1940. Moreover, the silk screen technique would have created posters with the scenes intact before adding the schedule block to cover part of the image. Surviving Glacier National Park posters and images also document that some Ranger Naturalist Service posters were made with and without the list of visitor services.

A November 1940 proposal for a new WPA project at WML cites 40 “preliminary designs for park posters” as accomplishments to date. That list distinguishes other kinds of posters made for parks from the park posters, as well as 20 “portable posters for parks.” The variation in poster designs described above could account for that high number, but it's possible that other park poster designs haven't been discovered. The WML's March and April 1939 monthly reports both refer to job 5748 "Make preliminary designs for park posters" for "headquarters office use," without specifying the parks. Both WPA and CCC labor was used in the design process.

It cost $12 for 100 printed posters. At only 12 cents per poster, it was a fast and affordable way for parks to advertise their programs for visitors. Although it’s been suggested that these small runs were made because the screen stencils started to degrade after about 100 uses, Silk Screen Stenciling as Fine Art (1942) states that the screens could produce many more prints than that. WML’s 1939 Miscellaneous Products catalog stated,

Be sure to order a sufficient quantity to supply your needs for the next few years inasmuch as once the screen is taken off it is necessary to recut the stencils in order to run the posters again.

Given the number of staff available to give programs and locations where parks advertised their programs, 100 posters would certainly have lasted most parks and monuments more than the recommended few years.

Written information about the inspiration for the design of each poster hasn’t been found. In some cases, the WML was creating dioramas for park exhibits around the same time, and similarities between those views and the posters can be readily seen. Other posters reflect the same iconic views in the 1934 national park postage stamp series. The posters for Great Smoky Mountains, Zion, and Yosemite national parks and Yellowstone’s Old Faithful geyser have more than a passing resemblance to their postage stamps.

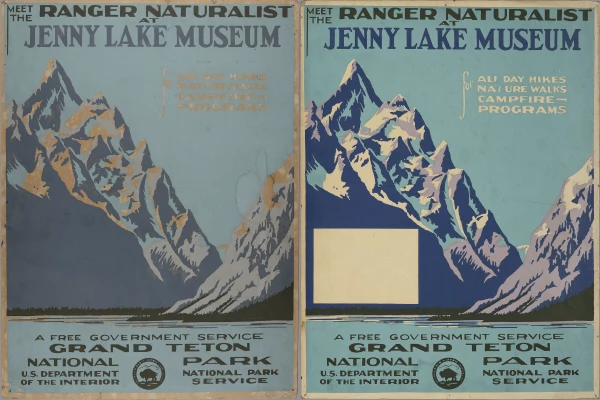

Grand Teton National Park, August 1938

The Grand Teton National Park poster features snow-capped purple and blue mountains viewed from across Jenny Lake. The trees at the water’s edge are tiny compared to the massive mountain peaks. It encourages visitors to “Meet the Ranger Naturalist at Jenny Lake Museum” for all day hikes, nature walks, and campfire programs.

The design for the poster was completed on August 25, 1938. The glacial diorama created by WML reflects the same mountain view, although the poster image is less expansive. At least two versions of the poster were created, with and without a white schedule box. This was the first in the park poster series, and Yeager wasn’t satisfied with it. On August 26, 1938, he wrote to Pinkley,

This poster for Grand Teton was made up more or less as an experiment and does not in any way represent the best which can be obtained by the process. Future posters, especially the lettering, will be of a much higher standard.

The artist responsible for the design is unknown. Only 100 posters were printed, but it’s not clear if that is 50 of each style or if a second run of posters was printed later. Although the poster doesn’t include the later “Made by WPA—CCC” designation, the design required seven CCC and 19 WPA “man days” to complete. It’s also not clear if that included printing, since the entry refers only to the design of the poster. The NPS History Collection has one of three surviving examples. The other two are in the Grand Teton National Park museum collection.

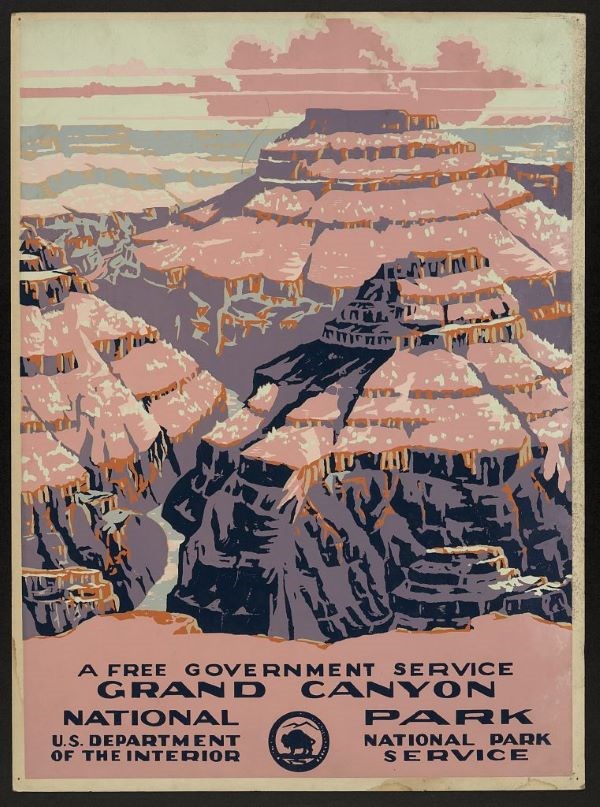

Grand Canyon National Park, November 1938

The Grand Canyon National Park poster is an expansive scene of the canyon under a white sky with fluffy pink clouds. Unlike the other six-color silkscreen park posters, it uses eight colors. The scene is rendered in dark and light pinks, with gray, rusty brown, blue, white, yellow, and black highlights.

The May 1938 WML monthly report records that “six posters were completed and shipped to Grand Canyon.” It's unlikely that they were from this series of silkscreened park posters, but no surviving examples have been found to confirm this. The December 1938 monthly report illustrates the Grand Canyon poster with the schedule block as “one of several posters announcing naturalist work. These posters have proven very popular with the various parks.” Despite this description, as printed the poster doesn’t refer to the Ranger Naturalist Service and doesn’t list visitor amenities. One design does have a white schedule block for parks to post their own activities. Another design without the schedule block was also printed.

Given that Powell was still working on the Zion diorama, it’s unlikely that he was involved in producing this poster. The designer is unknown. There are five surviving copies of this poster: three in the Grand Canyon National Park museum collection, one at the Library of Congress, and one in a private collection.

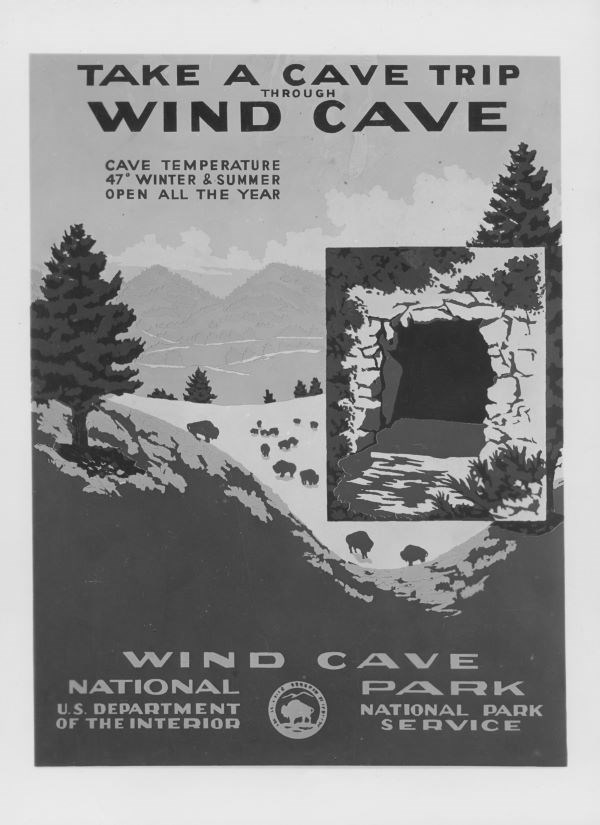

Wind Cave National Park, December 1938

This poster’s existence is known from documents and photographs in the NPS History Collection, but no surviving examples have been found. The poster features an inset with the original entrance to Wind Cave on a hilly landscape with trees and roaming bison. Text above the distant mountains reads, “Take a Cave Trip through Wind Cave” and “Cave temperature 47° winter and summer. Open all the year.” A stylized DOI seal is at the bottom center.

The October 1938 NPS Museum Division report noted, “Preliminary sketches for Wind Cave murals are being revised and will be submitted for approval when finished.” The “murals” were likely poster designs: the next month’s report noted, “Revised sketches for murals at Wind Cave are finished,” and the posters were printed the next month.

Although the December 1938 WML report noted, “Silk screen posters for Wind Cave National Park were completed and shipped,” the accompanying table of work status indicates that job number 6273 to make 100 posters for Wind Cave was only 25 percent complete. At that stage, the project had required one WPA, nine CCC, and two NYA “man days” to complete. It’s possible that printing this poster continued into January 1939.

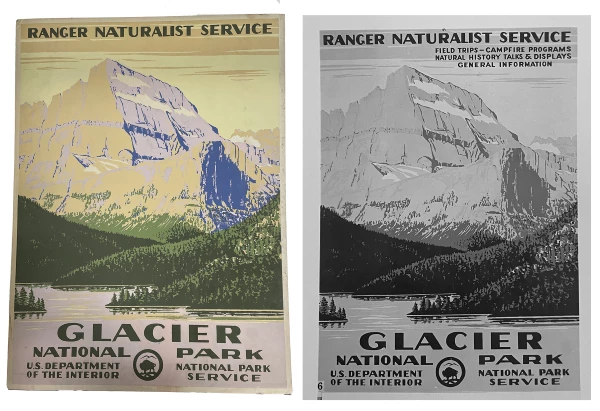

Glacier National Park, January–February 1939

The Glacier poster features Mount Gould, located about three miles north of Logan Pass on the Continental Divide. There were at least two versions of this Ranger Naturalist Service poster made. The one in the NPS History Collection doesn’t list specific visitor services. Another design is documented in the 1940 photograph series. It lists field trips, campfire programs, natural history talks, displays, and general information as visitor services. The border of the stylized DOI seal doesn’t have any markings on either version.

The December 1938 WML monthly report notes, “Work was started on another series of posters for Glacier National Park.” This language is interesting because it suggests there was a previous series of posters for the park and they were working on more than one new design. No examples of these earlier Glacier designs have been found. The January 1939 report noted that 175 posters were completed that month. The next month 125 were printed, suggesting a total print run of 300. It's possible they were a combination of two, or perhaps three, designs. The designer is unknown, although others have attributed it to Powell. The NPS History Collection has one of the two copies known to exist. The other is in a private collection.

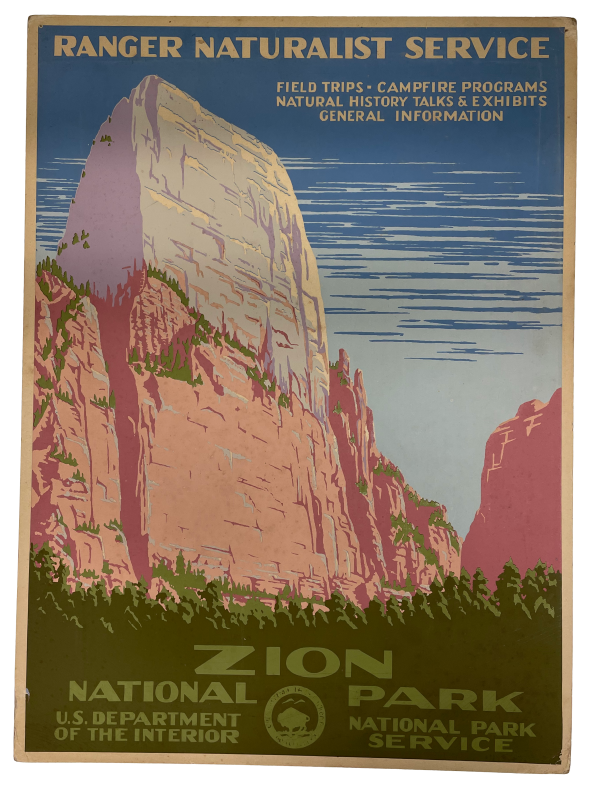

Zion National Park, February–March 1939

The Zion poster features a pink and purple Great White Throne rock formation, with trees at its base, against a blue sky. This Ranger Naturalist Service poster advertises field trips, campfire programs, natural history talks, exhibits, and general information. The stylized DOI seal appears to have some letters around its border, rather than random marks. However, they are not discernible.

The December 1938 monthly report noted, “Preliminary sketches for posters, requested by Zion National Park, were completed and forwarded for approval.” Study sketches were made in January 1939. Printing began in February, and 60 were finished by the end of the month. All 100 were finished and shipped to the park in March.

There are two surviving examples of this poster. One is in the Library of Congress. The one in the NPS History Collection belonged to Powell. The design has been attributed to him, seemingly because it was one of two park posters he kept copies of. However, there are no photographs of him working on it, and direct evidence that he was the artist behind the design hasn't been found.

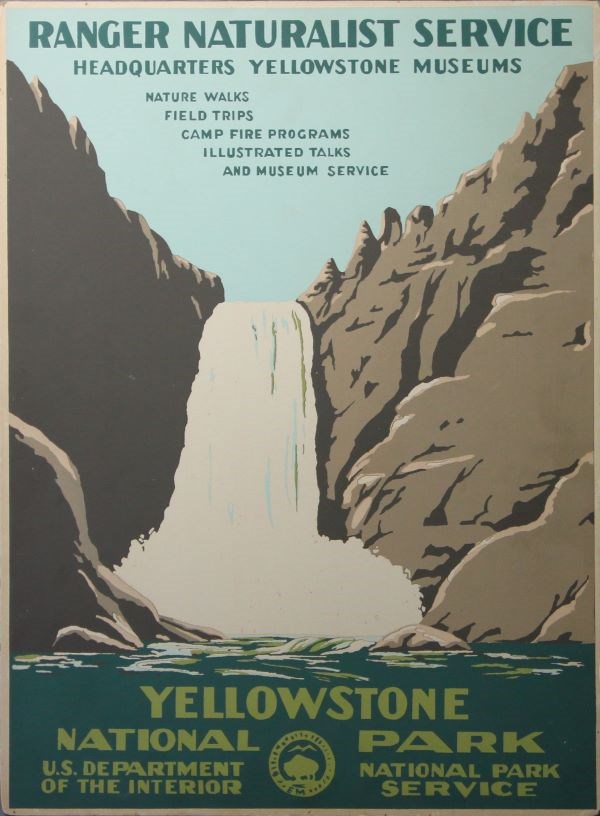

Yellowstone National Park (Yellowstone Falls), ca. March–April 1939

The first of two posters for Yellowstone National Park was probably completed before the Yosemite poster because the completed preliminary design for it can be seen on Powell’s drafting board in the photographs used in the July 1939 National Park Posters exhibit.

The design features the Yellowstone River waterfall crashing down between brown cliffs, beneath a light blue sky. The Ranger Naturalist Service poster highlights services at the park’s headquarters and museums, including nature walks, field trips, campfire programs, illustrated talks, and museum service. The stylized DOI seal at the bottom of the poster includes the letters “EM” in its border. If they are the designer’s initials, as has been suggested, then Powell didn’t design this poster (although he may still have overseen its printing).

It's likely that only 50 posters were printed, as one of the WML's accomplishments listed in a new 1940 WPA project request included "50 Falls of Yellowstone" posters, albeit in a confusingly worded sentence. The only surviving example of this poster is in the Department of the Interior Museum collection.

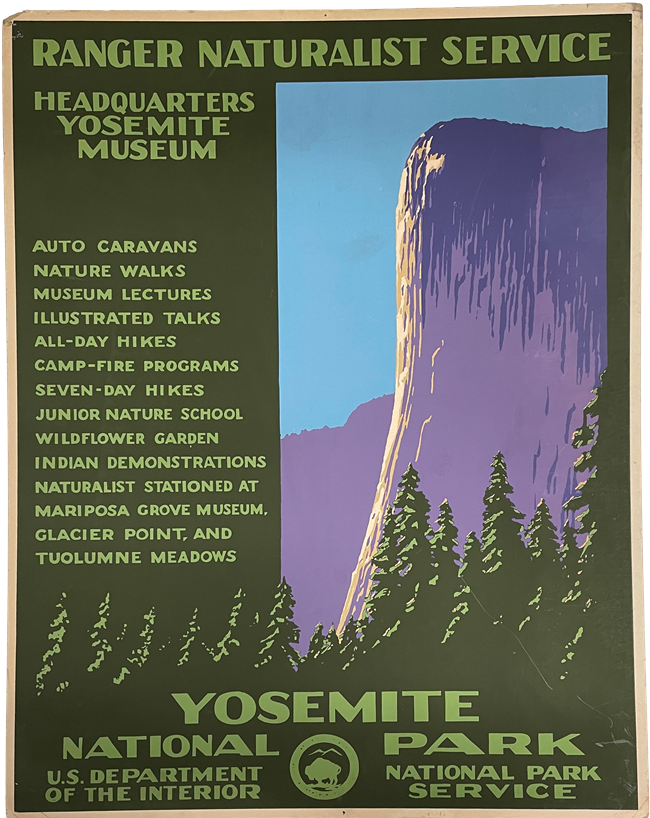

Yosemite National Park, February–April 1939

The Yosemite poster features the El Capitan rock formation in vibrant purples against a blue sky, its base fringed by pine trees. This Ranger Naturalist Service poster was created for park headquarters and the Yosemite Museum. Although the 1939 Miscellaneous Products catalog encouraged limited use of these, words take up almost the entire left half of the poster.

The services offered are auto caravans, nature walks, museum lectures, illustrated talks, all-day hikes, campfire programs, seven-day hikes, junior ranger school, wildflower garden, Indian demonstrations, naturalist stationed at Mariposa Grove Museum, Glacier Point, and Tuolumne Meadows. The stylized DOI seal at the bottom has markings to suggest text, but no letters are legible.

The design was probably created in December 1938 or January 1939 because we know that 30 percent of the posters were printed in February. Although the design has been attributed to Powell, that may not be the case if the exhibit photographs were staged. However, photographs do show him at the silkscreen press during production of the poster in April 1939, suggesting he was involved in the printing.

One hundred posters were printed between February and April 1939. The NPS History Collection has the only known surviving copy.

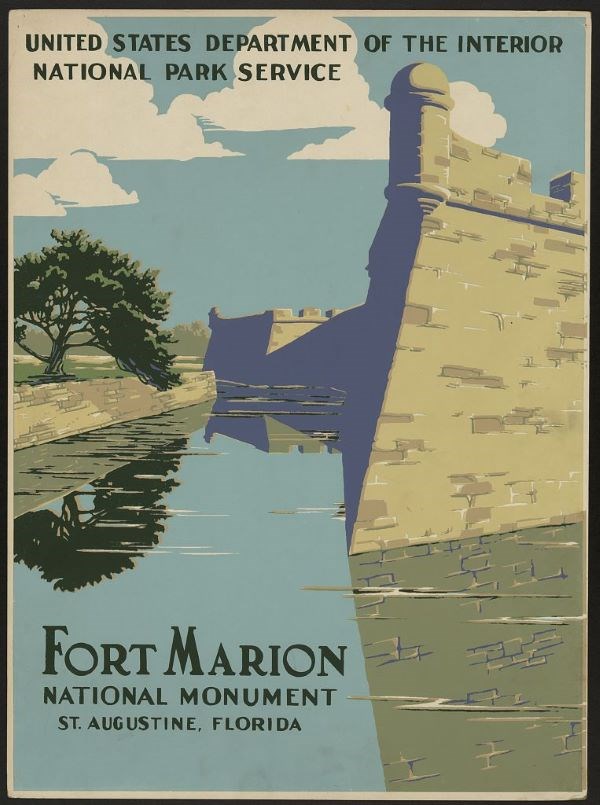

Fort Marion National Monument, July–August 1939

This poster for Fort Marion National Monument (now Castillo de San Marcos National Monument), features the fort’s exterior walls reflected in the water of the moat, under a cloudy blue sky.

As a historic site, the poster doesn’t feature the Ranger Naturalist Service banner. It also doesn’t list any visitor services. Text is limited to “Fort Marion National Monument St. Augustine, Florida” in the lower left corner and “United States Department of the Interior National Park Service” across the top. This keeps the fort and its reflections in the water as the focus. It’s also unique as the only WML park poster without a stylized DOI seal.

The WML records refer to the park as St. Augustine National Monument. They note that “work was started on 100 silkscreen posters” for the park. They were completed in August 1939. The designer of the poster is unknown. Given that no visitor services are listed on the poster, it’s possible that a version with the white schedule block was never made for this poster.

Only two surviving examples of this poster are known: one at the Library of Congress and the other in a private collection

Saguaro National Monument, July–August 1939

A poster not previously included in the park series was made around August 1939 for Saguaro National Monument (now a national park). No surviving examples or images of this poster have been found, but there is a reference to it in the work status table attached to the July 1939 WML report. Job number 8167 is described as “make 100 posters” for Saguaro. At the time it was only 10 percent complete, having used six WPA and two CCC “man days.” Given Yeager's description of why the silkscreen printing process was adopted, it seems reasonable to assume that this was also a serigraph.

One assumption that may have led to the Saguaro poster being excluded from the park poster series is that it wasn’t photographed with the other posters on May 5, 1940 (or perhaps the photograph never made it to the NPS History Collection). Since it wasn't discovered with the other images, and no surviving examples have been found, it was assumed that it wasn't part of this series. Given that more than one design was created for most parks, it's reasonable to assume that the set of 1940 photos isn't as complete as once thought.

The order for 100 posters fits the early pattern, as does the timing of the height of the park poster program and the needs of the national monument. Saguaro was part of the SWNM, managed by Pinkley. He and Yeager corresponded about the park posters in late 1938. SWNM naturalist Natt N. Dodge would have been capable of suggesting designs for a Saguaro poster. Moreover, a poster would have been an attractive proposition to the monument staff in 1939. The SWNM monthly reports note that a new information leaflet and preliminary displays at the park were created in January 1939. A new contact station at the south entrance was built in February. In March the CCC completed the Skyline Loop Road. A poster advertising the new ranger programs and visitor services planned for later that summer would certainly have been welcome.

There are two reasons that may explain why so little documentation of this poster exists. First, SWNM archeologist Charlie Steen worked at WML from February through April 1939 to oversee work on the White Sands exhibits and “other SWNM projects.” With Steen on site, it’s likely that more discussions and project decisions were made verbally. Second, the Saguaro custodian position was vacant from May through September 1939. As a result, no monthly reports were prepared for the monument to describe the poster or confirm its receipt.

Given that the park was a national monument at the time and its ranger programs was in its infancy, it's unlikely this poster would have had the Ranger Naturalist Service header. Until or unless more information—or indeed one of the 100 posters—is found, little else can be said about this poster.

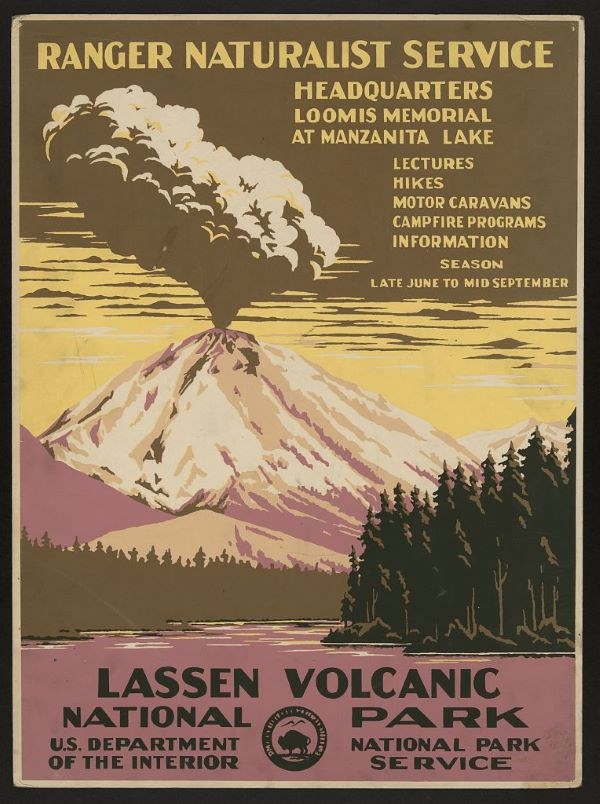

Lassen Volcanic National Park, August–September 1939

The Lassen Volcanic National Park poster shows Lassen Peak erupting, with a plume of ash rising above it. This Ranger Naturalist Service poster featured Headquarters and the Loomis Memorial at Manzanita Lake. It advertises lectures, hikes, motor caravans, campfire programs, and information and informs visitors that the park’s season is late June to mid-September.

The border around the stylized DOI seal includes the letters “DM.” As noted earlier, if these are initials, they could refer to Dale Miller and suggest that he either designed the poster or completed the design in color before it was printed.

The WML records note that study sketches for this poster were made in July 1939. The next month 93 of these posters were completed. In September WML reported, “One hundred silk screen posters were completed and shipped to Lassen Volcanic National Park.” The total number of posters printed is believed to be 100. There are two known examples of this poster: one at the Library of Congress and the other in a private collection.

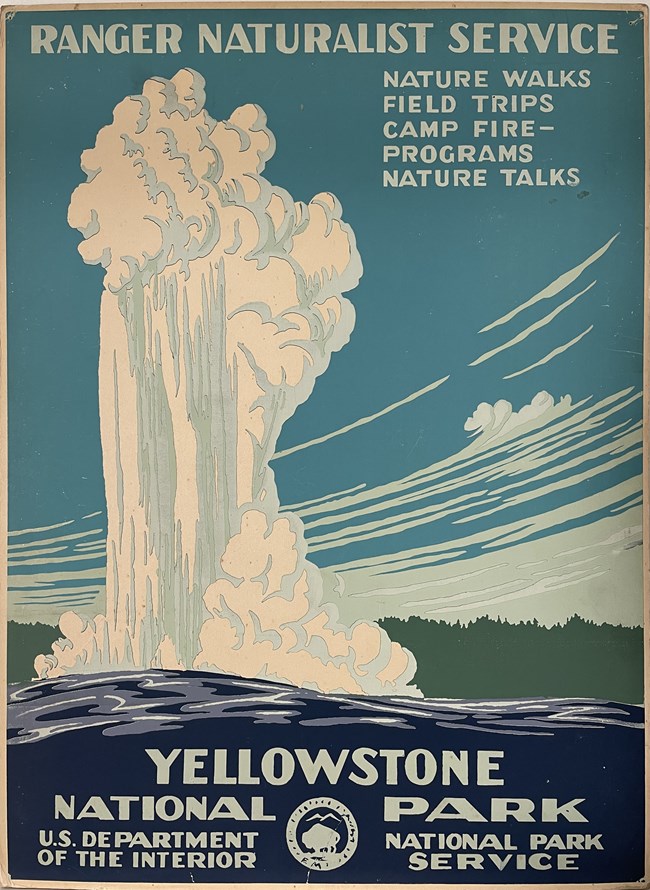

Yellowstone National Park (Old Faithful), September–October 1939

A second poster for Yellowstone National Park was also created in 1939. The design features Old Faithful geyser erupting into a blue sky. The Ranger Naturalist Service poster advertises nature walks, field trips, campfire programs, and nature talks.

The WML reports state that the study sketches for proposed posters were made in June 1939. It is in a preliminary stage of design in the June 23, 1939, photo used in the National Park Posters exhibit. As noted earlier, this suggests that the photos of Powell at the drafting board were staged. That photo, together with the fact that Powell had one of these posters in his personal collection, have been the basis for suggesting that he was the designer. However, like the Yellowstone Falls poster, this one has the letters “EM” in the border of the stylized DOI seal, suggesting that Powell wasn’t the designer.

Both the September and October 1939 NPS Museum Division monthly reports record that 100 posters were finished each month. Yet another report indicates that the posters weren’t finished in September, suggesting perhaps the total was only 100.

There are three known examples of the geyser poster. The one in the NPS History Collection belonged to Powell. The other two are in the Library of Congress and the Department of the Interior Museum.

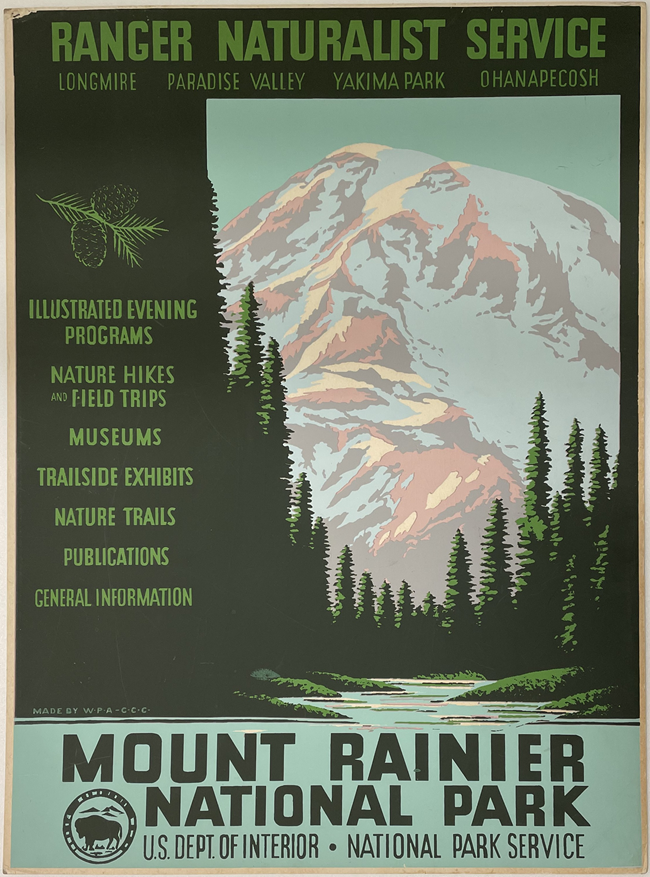

Mount Rainier National Park, January 1940

The Mount Rainier poster, unsurprisingly, features a snow-covered Mount Rainier, with fir trees and a river at its base.

This Ranger Naturalist Service poster highlights the Longmire, Paradise Valley, Yakima Park, and Ohanapecosh areas of the park, making it the only one in the series to include a Native American name for a location in a park. It’s also the only poster to feature a line drawing of two fir cones on a branch above the list of services. Visitors would be offered illustrated evening programs, nature hikes, field trips, museums, trailside exhibits, nature trails, publications, and general information.

Study sketches for this poster were made in July 1939, but the poster wasn't printed until January 1940. There are several aspects of this poster that suggest a different designer or design team. The layout of the text at the bottom of the panel is different from earlier posters. The stylized DOI seal is now at bottom left rather than bottom center, and it has an open section of border below the bison. Although the designer of this poster cannot be confirmed, it includes the new phrase “Made by WPA—CCC,” suggesting either a change in how the WML posters were created or new requirements for marking products made by New Deal programs.

More copies of this poster survive than most others. The NPS History Collection has one of six originals known to exist.

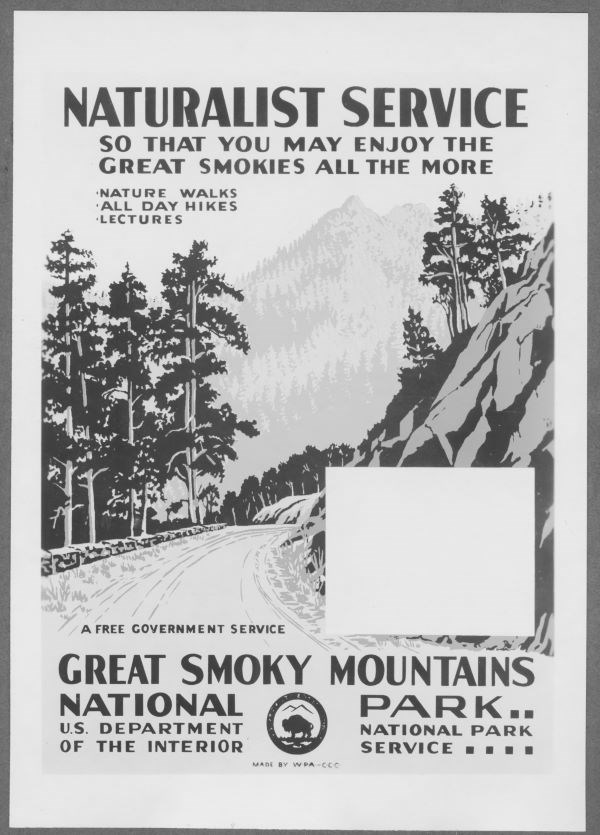

Great Smoky Mountains National Park, April—May 1940

No examples of this poster have been found. Black and white images in the NPS History Collection have been the basis for reproductions of it, with contemporary colors selected by the printers.

The original poster featured a mountainside road under the “Naturalist Service So That You May Enjoy the Great Smokies All the More” banner. The services were limited to nature walks, all day hikes, and lectures, which reflects the limited programs at the newly developed park. The poster was likely commissioned in anticipation of the park’s formal dedication in September 1940.

The longer park name appears to have given the designers problems, and they added small decorative squares after some words to retain the same visual right margin. “Made by WPA—CCC” is printed beneath the stylized DOI seal, which is in the middle of the poster again. The designer is unknown. It’s likely that another version—without the white schedule block—was also made.

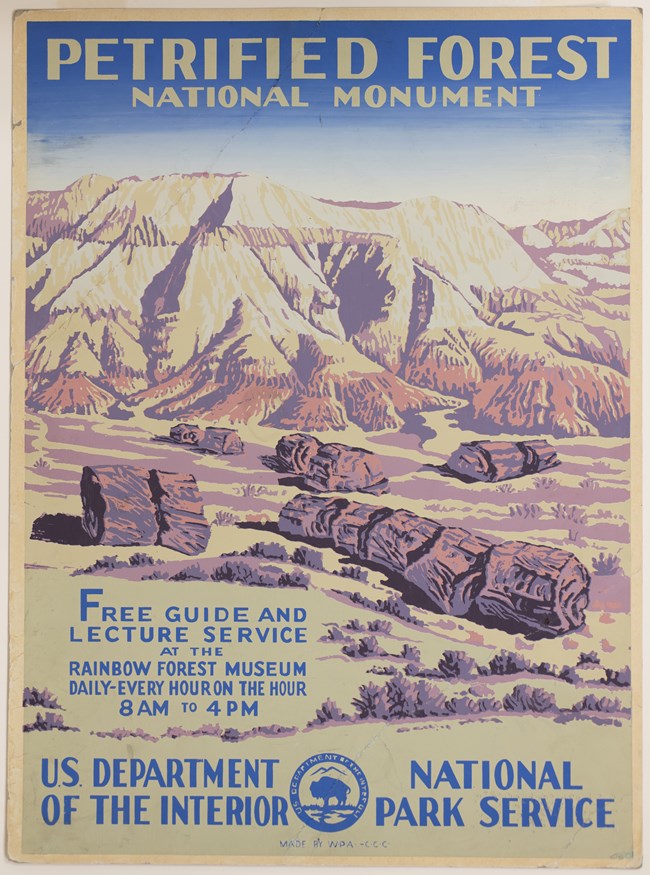

Petrified Forest National Monument, April 1940

The poster for Petrified Forest National Monument (now national park) features large, petrified tree trunks lying on the ground with mountains in the background.

The poster is not one of the Ranger Naturalist Service designs, but it advertises a free guide and lecture service at the Rainbow Forest Museum daily, “every hour on the hour” from 8am to 4pm. Unlike the othe posteres, this DOI seal includes discernible letters around the border suggesting “US Department of the Interior,” although the last word is unclear. Like the two earlier posters, it's also marked “Made by the WPA—CCC” below the seal.

Although the WML report doesn’t refer to this poster by name, it references completion of 500 silkscreen posters for the Southwestern National Monuments as it discusses the Painted Desert Museum, making this a reasonable assumption. Despite the larger run number, only one example has been found. It’s part of the Petrified Forest National Park museum collection.

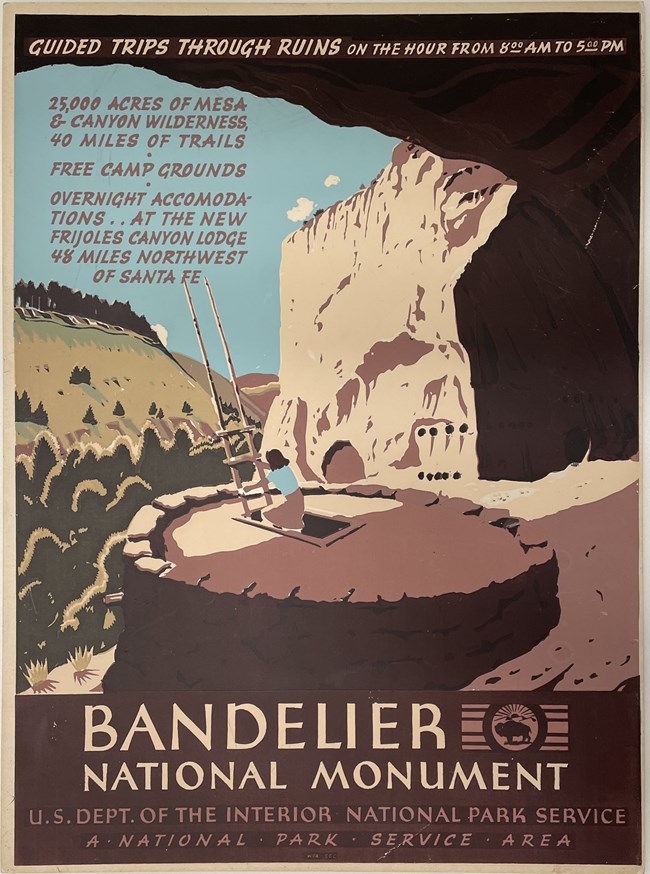

Bandelier National Monument, March–April 1941

The Bandelier National Monument poster isn’t a Ranger Naturalist Service poster. Instead, the heading encourages visitors to take “Guided Trips Through Ruins on the Hour from 8:00 am to 5:00 pm.” The main image is that of a woman descending a ladder into Alcove House Kiva, which was reconstructed in 1937. In the sky above, the text describes 25,000 acres of mesa and canyon wilderness and 40 miles of trails. Amenities were free campgrounds with overnight accommodations at the new Frijoles Canyon Lodge 48 miles northwest of Santa Fe.

The text layout at the bottom of the poster is also different from the earlier posters. The stylized DOI seal includes the sun’s ray behind the bison. It is presented as the central image of what looks like a striped, rectangular DOI flag. At the bottom, beneath “A National Park Service Area,” are the faint letters “WPA—CCC.”

Loss of staff at WML meant that it took longer to complete this poster. Interestingly, the January 1941 report records that the “designs for posters” were 98 percent complete. This suggests that more than one poster design option was in consideration, or that there was a version with the schedule block that hasn’t been found yet. Printing didn’t begin until March, and only 75 of 100 posters were finished. The remaining 25 were printed in April (although the accomplishment report refers to all 100 being completed that month). The designer is unknown. The NPS History Collection has one poster in its collection. The other surviving examples are at Bandelier National Monument.

Rocky Mountain National Park, June 1941

Although the Bandelier poster has traditionally been deemed the last in the park poster series, the March 1941 WML monthly report states that sketches for posters were in process. Later in the report it clearly notes that one of the tasks was to “design ranger-naturalist poster” for Rocky Mountain National Park. At that time the job was 10 percent complete. The next month’s report notes that the poster design was finished. In June “650 posters, advertising the interpretive work, were made for Rocky Mountain National Park.” It’s not clear if all 650 of them were from the park poster series, but given that the design was finished in April, it is reasonable to believe that at least 100 of them would have been Ranger Naturalist Service posters.

This poster has not been previously identified, probably because the NPS History Collection didn’t have an image of it when previous poster research was undertaken, and no surviving examples have been found. Others may have assumed the large number referred to something like a fire poster (see below). However, the description of it as a ranger naturalist poster puts it in the park poster series. The original images in the NPS History Collection were all taken on May 5, 1940, and wouldn’t include posters created after that date. The designer and design of the Rocky Mountain poster is unknown.

The Other WML Posters

The WML poster program wasn’t limited only to the better-known park posters, which may explain why more of them weren’t prepared during this period. Although a few photographs of them have been found, most of the designs and designers are unknown. These posters were usually printed in larger quantities than the park posters, but the only known surviving example is a "Paradise Lost" poster in a private collection. Information about these other posters from the WML monthly reports is summarized below.

- California Conservation Week: Poster study sketches were prepared for the NPS Region IV office, January 1939.

- Yosemite: Label 150 silk screen posters, May 1939. The 100 park posters were completed the previous month. It's unclear what this refers to.

- Ski Warning Poster: 100 ski posters, January 1940. This poster was designed by the staff at Mount Rainier National Park as part of a safety program and printed by WML. The poster was subsequently made for Rocky Mountain National Park and other parks with winter activities. No known surviving examples.

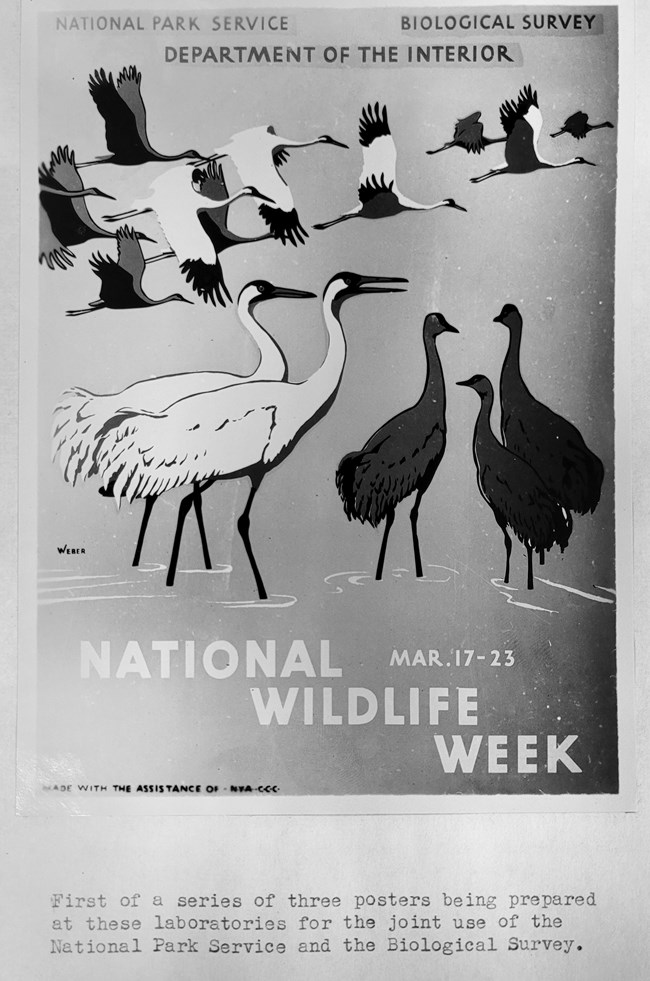

- Wildlife Week: 3,600 silk-screen posters in three designs, made for use by the NPS and the Bureau of Biological Survey, February 1940. The WML monthly report contains a photograph of one of the three designs used. The report goes on to say that there was much hardship getting this job done due to heavy rains that caused water leaks within WML, and that the “head of the silk screen department spent approximately two weeks of his own time in an effort to complete the posters on schedule.” Although some have assumed that Powell was the head of the silkscreen department, that has not been confirmed. Although the poster designers are unknown, the birds featured on the first poster in the series were drawn by NPS artist Walter Weber. This poster is unique because it includes both bureau names in the header and "made with the assistance of the NYA—CCC" along the lower left edge.

- Yosemite: 100 “small silk screen posters, warning of fire danger,” July 1940. These posters were to be placed in desk holders and distributed throughout the park.

- Various National Parks: “150 [posters] were produced for use throughout the various national parks during the coming winter,” July 1940.

- Fire Prevention: “1,000 silk-screen fire prevention posters were turned out for various parks,” August 1940.

- Fire Prevention: “500 posters fire posters, titled ‘Paradise Lost’ were finished and sent to the Washington and Regional Offices,” October 1940.

- Various National Parks: “750 silk screen posters” without description, October 1940.

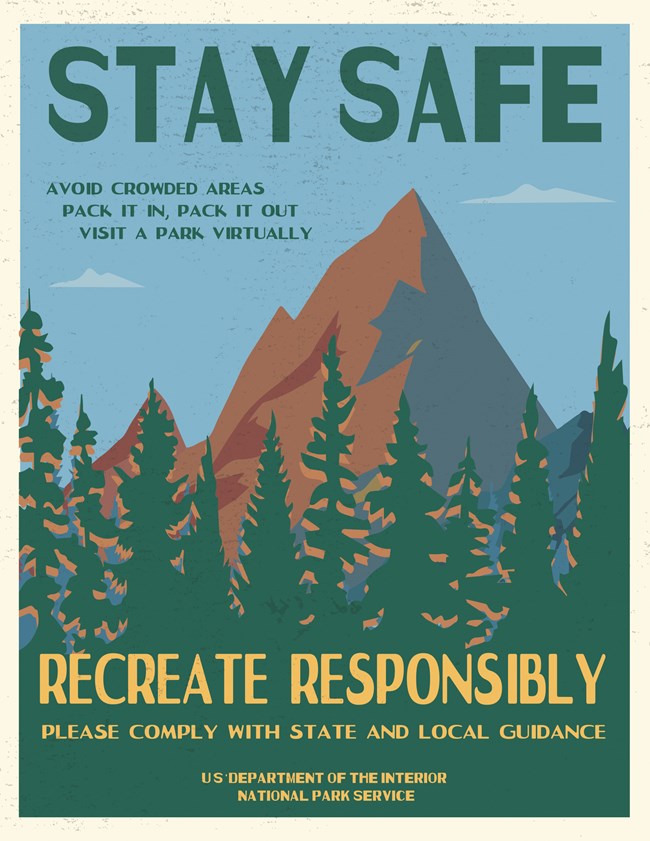

- Fire Prevention: 500 “Paradise Lost” and 400 “Reflections on Man’s Carelessness” fire prevention posters were made by CCC enrollees, April 1941. This appears to be a reprint of the “Carelessness” posters pictured in a July 1940 photograph.

- Fire Prevention: “The CCC enrollees ran three hundred fire prevention posters by the silk screen process,” August 1940. These are probably the two designs of “Human Carelessness” created for headquarters as mentioned later in the report.

- Fire Prevention: “CCC enrollees completed 900 silk screen fire prevention posters,” April 1941.

- Yosemite: 300 “No Smoking” and 300 “Campgrounds,” May—June 1941.

None of the designers and few of the designs are known. As mentioned earlier, a "Paradise Lost" poster is in a private collection. The simple poster features black, charred trees against a fire-orange sky. "Paradise Lost" is the title and "through carelessness with fire" is printed in orange in the scorched earth. "Made by the WPA—CCC" and "National Park Service" is the only other text. The poster doesn't reference the DOI or use the DOI seal.

"Paradise Lost" and a few photographs in the NPS History Collection reveal that different design styles were used at the WML even as the park posters were being created.

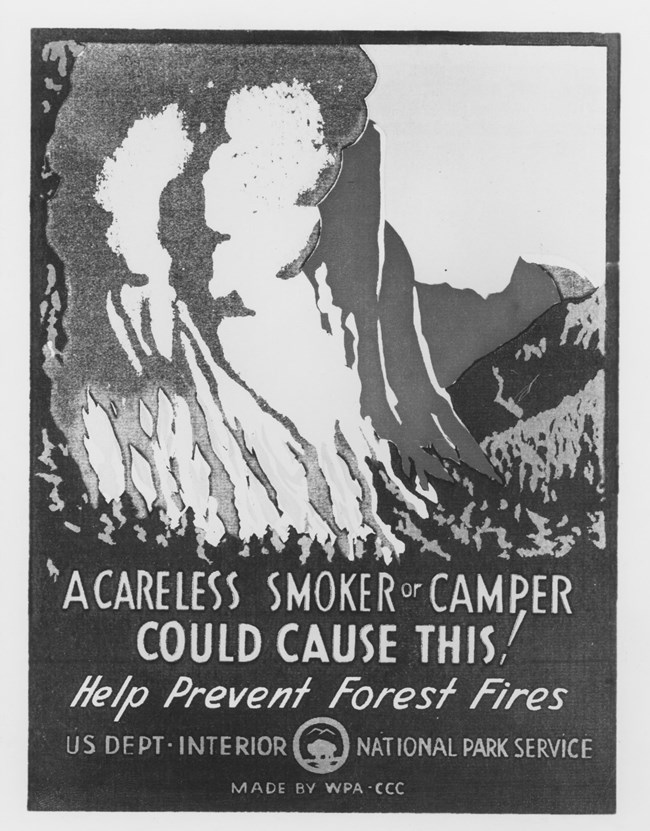

A black-and-white photo, dated July 23, 1940, may document the “small silk screen posters warning of fire danger” made for Yosemite. They were to be placed in desk holders and distributed throughout the park. The poster features a smoky fire raging across the landscape, with Half Dome in the distance. The text reads, “A Careless Smoker or Camper Could Cause This! Help Prevent Forest Fires.” The stylized DOI seal is in the middle at the bottom of the poster, just above “Made by WPA—CCC.” No examples of this poster have been found.

A second photo, this one from a WML report, reveals three “Reflections on Man’s Carelessness” posters. In one, a fire-charred landscape is reflected in the waters of a lake. The other two posters are more ambiguous. They appear to be slightly different designs. The artist is unknown and sits with his back to the camera.

Another WML photograph, dated January 15, 1941, features three posters on the walls behind CCC workers creating accessories for a model of La Purisima Mission. Two of them are from the Indian Court Federal Building series of seven posters. Designed by Louis Siegreist for the 1939 Golden Gate International Exposition, they weren’t printed at the WML. However, some of the experienced silkscreen printers from the WML were loaned to the project so it could be finished on time.

The third poster is titled “Winter Recreation” and features a skier. It was created for the United States Travel Bureau, most likely by the WML artists. The program was part of the NPS from 1937 until 1940.

Finally, another NPS History Collection photo illustrates a second previously unknown poster. Although the artist is unknown, the caption indicates he was a Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) enrollee. The date of the photo, February 25, 1931, is believed to be a typo—because the CCC wasn’t formed until 1933 and the WML poster program didn’t start until 1938—with the photo dating to 1941. The photographer, listed only as Cather, was actively taking photographs for the NPS in the late 1930s and early 1940s. The caption notes that the poster was going to be created through the silkscreen printing process. Called “Protection of Flowers,” it's not clear if this was a unique poster or part of a larger series. No reference to that title has been found in the WML records. The printing run for this poster is also unknown.

The End of the WML Poster Program

In January 1939 recently enacted legislation affected the WPA artists at WML. The law required that people working 18 months would have to be “separated” (laid off) for at least 30 days with no assurance that they could return. Complaints about the effects of this requirement on WML’s work—even when key people were brought back—are mentioned in subsequent monthly reports.

Beginning in 1940, the WML began to lose its talented staff to higher-paying jobs in industry as the United States prepared to enter World War II. A report from the Museum Division, Branch of Research and Information, in November 1940 laments, “it is apparent that within a short time the WPA project…will be affected by the defense program as workers are gradually leaving to accept jobs in shipyards, airplane plants, etc.”

This trend continued in 1941. The February monthly report began with, “The defense program is making itself felt by the gradual diversion of workers into defense industries and by our inability to locate adequate replacements. In time this will seriously endanger the output of these Laboratories.” The next month’s report related, “One after another, workers left to accept employment with the Defense Program.” The WML Art Department also continued to lose talented staff when their 18 months of service expired. In May Yeager wrote,

During the first days of this project, we grumbled because when we requisitioned a plaster caster from WPA, we got a dental technician; when we requisitioned an artist, we got a sign painter; and when we requisitioned a lantern slide colorist, we received a dear little old lady whose hobby was painting teacups. And how we moaned! But during these times we would welcome with open arms the sign painter, the dental technician, and even the dear little old lady.

The Art Department began to refuse new work, hoping that it could complete what was in progress before it lost the last of its staff. Eventually, entire WML departments closed for lack of workers. All WPA projects at the WML came to an end in July 1941, although there is evidence that CCC enrollees were still printing silkscreen posters at this time. Yeager’s monthly reports from June and July 1941 have a requiem-like tone to them,

I feel that I am about to write a death notice! In place of the two to three hundred workers which we have had on occasion in the past, our staff now consists of one museum artist, two stenographers, two CCC enrollees, and [myself]. Work will continue on a scale dependent upon the number of CCC enrollees made available to us. Now that it is no longer possible to rely upon such agencies as CWA [Civil Works Administration], NYA, and WPA to produce museum exhibits for the national parks and monuments, there must be a concerted effort on the part of everyone interested in the interpretive work to obtain appropriations for employment of adequate personnel to carry on the museum program.

The WML’s WPA project officially ended on July 29, 1941. By the end of August, for the first time since 1934, there were no CCC enrollees attached to the WML Berkeley office. Moffett, funded by CCC but not an enrollee, stayed on until about July 1942. A small lab was set up in the Old Mint Building in San Francisco to continue WML’s work with its small staff. A planned public sale of the surplus furniture and equipment was cancelled, and the materials were sent to various branches of the US military.

Posters with a Purpose

Although the WML made thousands of silkscreened posters between 1938 and 1941, only about 40 park posters and a couple of others are known to survive. This is not uncommon. Estimates are that over two million posters, made from 35,000 designs, were printed by New Deal poster programs, yet only about 2,000 survive. All New Deal posters are rare survivors.

From today’s perspective it might seem neglectful that so few of the WML posters survive, but it’s important to remember that they were created to advertise parks and ranger programs, promote a specific event, or warn against fire danger, at a specific point in time. They were cheap to make but sturdy enough to last a few years in harsh park environments. In effect, they were designed to be disposable, just as ranger programs posted in campgrounds, amphitheaters, and visitor centers are today. The posters often faded while on display and were discarded. Some were pinned to bulletin boards and may have weathered outdoors. Over time, some were cut up for file drawer dividers, used in plant presses for park herbarium specimens, or recycled for other uses. In some cases, employees undoubtedly took copies of the posters home when offices and visitor centers changed or rescued them from the trash. These copies became part of personal collections, some of which were eventually sold at garage sales or auctions. Other copies stayed in parks in drawers or as office art. A few eventually made their way into park museum collections. Many were donated back to the NPS over time.

The historical context of the posters is also important. They were created in the years just before the United States entered World War II. After the war, NPS interpretation—and indeed, the world—had changed. Based on available records, continuing with the pre-war poster series wasn’t even considered. The NPS focused on modernizing its facilities and programs as part of its Mission 66 initiative. When the NPS resumed a poster program in 1968, mid-century modern architectural and interior designs dominated American tastes.

Modern Art?

In the 1990s silkscreen reproductions of the 14 park posters, documented by photos in the NPS History Collection and surviving examples, began to come onto the market. As their popularity increased, new posters in the “WPA-style” were created for parks that never had them historically. Before long the images were used on calendars, puzzles, mugs, clothing, and other gifts. The graphics have become so ubiquitous that online videos instruct users how to recreate the font and style of WPA posters. Even the NPS frequently creates digital content in the “WPA style” to advertise parks, programs, and visitor safety.

From a graphic design standpoint, the WML park posters and the many derivatives they inspired are more popular—and numerous—today than they were when they were made. Photographs of other posters made at WML at the same time as the park posters demonstrate that the “WPA style” now firmly associated with the NPS was just one graphic design style used for some posters during a three-year period.

Given the diversity of styles produced, we'd love to see other examples. If you think you have a WML poster in your collection, please contact the NPS History Collection archivist.

Sources

--. (1934, July 22). “Artists Under SERA Work at Auditorium. “ Oakland Tribune (Oakland, California), p. 36.--. (1937, February 13). “The Oakland Sketch Club Show.” Stockton Evening and Sunday Record (Stockton, California), p. 12.

--. (1942, May 2). “Intention to Wed.” The Oakland Post Enquirer (Oakland, California), p. 7.

--. (1973, March 27). “Duffield.” Concord Transcript (Concord, California), p. 13.

--. (2005, December 11). “Dale Allen Miller.” Oakland Tribune (Oakland, California), p. 26.

--. (2023, October 12). “The Case of the Missing Park Posters: Ex-Ranger Hunts for New Deal-Era Art.” Retro Report. Accessed October 2023, at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QnY3QfwzVGI&t=302s.

Ancestry.com. Various birth, death, marriage, US census, and military records for Elmer Duffield, Dale Miller, and C. Don Powell.

Assembled Historic Records of the National Park Service (HFCA 1645). WML and SWNM records. NPS History Collection, Harpers Ferry, WV.

Berger, Erin. “Meet the National Parks’ ‘Ranger of the Lost Art.’” (2020, August 25). The New York Times. Accessed October 26, 2023, at https://www.nytimes.com/2020/08/25/style/ranger-doug-leen-wpa-national-park-posters.html

Biegeleisen, J.I. and Cohn, Max. (1942). Silk Screen Stenciling as Fine Art. McGraw-Hill Book Company, Inc., New York.

Burke, Claire, and Sekhar, Sanjana. (2019). Imprint: Printmaking and America’s National Parks. Accessed October 2023, at https://vimeo.com/325513576

Dungan, H.L. (1937, July 11). “13 Water Colorists Do Good Work.” Oakland Tribune (Oakland, California), p. 44.

John Nelson Maps. (2020, December 7). “A WPA Poster Style for ArcGIS Pro.” Available online at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=812dPOE572o

Leen, Doug. (2016, May 10.) Pers. comm. (email correspondence) with Tracy Baetz, Chief Curator, U.S. Department of the Interior Museum.

Leen, Doug. (2021, March 3). Pers. comm. (email correspondence) with Tracy Baetz, Chief Curator, U.S. Department of the Interior Museum.

Leen, Doug. (2022, July 9.) Pers. comm. (email correspondence) with Nancy Russell, Archivist, NPS History Collection, Harpers Ferry, WV.

Lewis, Ralph H. (1993). Museum Curatorship in the National Park Service 1904-1982. National Park Service Curatorial Services Division, Washington, DC.

Library of Congress. (undated). “Posters: WPA Posters. Background and Scope.” Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division. Accessed October 26, 2023, at https://loc.gov/pictures/collection/wpapos/

National Archives and Records Administration (2024, December). Scan of Chester Don Powell's WPA personnel file. Provided to the NPS History Collection.

National Park Service. (1938, November). “Travel Bureau Issues Bulletin.” The Regional Review, Vol. I, No. 5. Accessed on December 20, 2023, at https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/regional_review/vol1-5l.htm

National Park Service. (2023, January 10). “50 Nifty Finds #7: The Waugh Factor.” NPS History Collection, Harpers Ferry, WV. Accessed October 31, 2023, at https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/50-nifty-finds-9-green-stamps.htm

National Park Service. (2023, March 16). “50 Nifty Finds #9: Green Stamps.” NPS History Collection, Harpers Ferry, WV. Accessed October 31, 2023, at https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/50-nifty-finds-7-the-waugh-factor.htm

National Park Service. (2023, August 10). “50 Nifty Finds #32: A New Deal for Artists.” NPS History Collection, Harpers Ferry, WV. Accessed November 1, 2023, at https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/50-nifty-finds-32-a-new-deal-for-artists.htm

NPS Historic Photograph Collection (HFCA 1607). NPS History Collection, Harpers Ferry, WV.

Powell, Richard. (1998, October). “Biography of C. Don Powell.” NPS History Collection accession files, Harpers Ferry, WV.

Ranger Doug Enterprises. (2023). “History.” Accessed December 20, 2023, at https://www.rangerdoug.com/history/

Tags

- bandelier national monument

- castillo de san marcos national monument

- glacier national park

- grand canyon national park

- grand teton national park

- great smoky mountains national park

- lassen volcanic national park

- mount rainier national park

- rocky mountain national park

- saguaro national park

- wind cave national park

- yellowstone national park

- yosemite national park

- zion national park

- nps history collection

- hfc

- art

- poster

- posters

- serigraph

- silkscreen

- wpa

- wpa project

- ccc

- nya

- western museum laboratories

- graphic design

- graphic identity