Last updated: March 27, 2023

Article

50 Nifty Finds #20: An Accidental Artist

Walter A. Weber wanted to be a naturalist, not an artist. He was talented in both areas, but it was his art that earned him an income and brought him acclaim. His work applied the qualities of fine art to scientifically accurate portraits of birds, mammals, fish, and other animals. Although better known for illustrating National Geographic articles, Weber’s work for the National Park Service (NPS) added significant pieces to NPS museum collections. As chief scientific illustrator in the NPS Museum Branch, Weber created expressive and engaging images that educated the public about native and endangered species.

Walter Alois Weber was born in Chicago, Illinois, on May 23, 1906. He attended grammar and high schools in the Near North Side neighborhood of Chicago. As a child he wanted to be a naturalist, but he recalled in a 1971 oral history interview that, “Drawing was always a hobby with me. I enjoyed doing it, but I had no intention of being an artist.” He was encouraged by two teachers, one of whom encouraged him to take his sketch pad to the zoo. The other took him to the Church School of Art, a private school in Chicago. She paid his tuition for the first term. He went on to win a scholarship for another year. From the age of nine, he took art classes on Saturday mornings.

Another influential teacher was Dr. Holtzman, the zoology teacher and assistant principal of his high school. He introduced Weber to Dr. Wilfred H. Osgood, curator of zoology at the Field Museum. As a result, he worked at the museum for several summers.

Weber also attended the Chicago Art Institute. He paid tuition for a semester but then worked there for three years on scholarship. He stopped going to art school when he began studying at the University of Chicago about 1923. He graduated from there in 1927 with a BS in zoology. He completed another year at the Art Institute but quit when the Field Museum offered him a chance to join an expedition to the South Pacific.

Weber was at loose ends because a galley fire on the ship delayed the trip by several weeks. With his materials sent ahead to Boston he had little to do. In the meantime, he met Grace Kiernan, a student at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, who was researching mammals of Lancaster County, Nebraska. He offered to help with her research. Dr. Osgood told him, “Go help your girlfriend” because he had been “nothing but a pest around here ever since you got all packed up.” As Weber recalled, he “showed her how to set a trap line and how to make study skins and do all the necessary data on them. And then one day it rained and sleeted and froze. We couldn’t go out to see the traps, so we decided to get married.” They married in Lincoln in fall 1928, two days before he left for the expedition.

Weber served as artist and ornithologist on the Crane Pacific Expedition. Besides collecting bird specimens, he drew about 130 Pacific reef fishes, as well as birds and mammals. He was gone for 11 months. When he returned in 1929, he was immediately asked to go to Bermuda to paint local fish for a private collection. He went on the condition that Grace could join him for two weeks at Christmas. The Webers determined that in the first 16 months of their marriage, they lived together about three weeks. They would eventually have three children. Their first daughter was born in 1934. Twin daughters followed in 1937.

After the Crane expedition, Weber’s paintings were exhibited at the Field Museum. Dr. Thomas S. Roberts at the University of Minnesota saw them and asked him to illustrate his book Birds of Minnesota. Weber recalled, “I think I did 20 or 25 plates for that book.” For the project, he traveled to British Columbia to study with Major Allan Brooks, one of the most important bird illustrators in North America. Weber was there for about four months, collecting birds while working with Brooks on the paintings for Roberts’ book. He later recalled, “I got commissions and did a lot of art on the side until eventually I got so I was doing more art work than anything else. I started out with no intention of being an artist. It just happened.”

He returned to Chicago in 1929. For the next two years, he worked as a scientific illustrator at the Field Museum. He remembered, “I did some background painting for the big groups [dioramas], particularly the underwater ones.” In 1931 he took a job with the Century of Progress International Exposition, also known as the Chicago World’s Fair. For two years he worked on biological exhibits and paintings for the fair, which opened in June 1933. Weber freelanced for most of the next year. He illustrated several children’s books in the 1930s including Traveling with the Birds (1933), Homes and Habits of Wild Animals (1934), and Our Friendly Animals and Whence They Came (1938).

Weber recalled, “By [about 1934] the Depression was beginning to catch up with everybody, including me.” He began to look towards the NPS for employment. He was interested in a ranger job at Grand Teton National Park as they wanted to hire someone with birding experience. Although that job was filled by someone else, Weber was asked to submit an application for a wildlife technician position. In 1935 he got a Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) appointment as a wildlife technician in Oklahoma City. Next, the CCC sent him to Austin, Texas. During his year in Texas, he did some survey work at Big Bend National Park as well as work in state parks. He got to know the staff in the zoology department at the University of Texas. To celebrate the centennial of Texas statehood, a museum was proposed. Weber was asked to help, so he took a sabbatical from the CCC and worked for the University of Texas, creating biological exhibits.

As Weber recalled:

While I was in Texas, Carl Russell, who was then head of the museum division of the NPS, was interested in getting me to work in Washington. But somehow or other things got balled up more or less. I got disgusted waiting for this transfer to be made, so I just took off and went to the Tetons and spent about two weeks fishing there and had a real good time. Finally, they caught up with me and said that my appointment was open in Washington.

In 1937 Weber and his family moved to Washington, DC, where he served as chief scientific illustrator with the NPS Museum Division. One of his special assignments was to create a series of paintings and line drawings to illustrate a book on endangered wildlife. It was eventually in 1942 published under the title Fading Trails: The Story of Endangered American Wildlife. Weber recalled,

The original idea was to make a picture portfolio with a paragraph on the back of each page giving the description of the animal and its status, and so forth. I had the paintings about finished when Mr. [Victor] Cahalane had to stick his nose in it and said, “No, this won’t do. We’re going to make a book out of it. This is too important a thing to just be a picture portfolio.” So, then they got all these guys in on it. When they started out, they had a least a dozen different authors, each writing on a certain species. It just got out of hand. It got to be ungainly. In the meantime, we got into [World War II] so they took the money away from us. So, what would have been a nice picture portfolio turned out to be what I would say is a lousy book.

He created 24 paintings and 12 pen-and-ink drawings for the book. Only four of his paintings were printed in color when the book was released. Most of Weber’s paintings from Fading Trails are part of the NPS Washington Office Collection, managed by the NPS Museum Management Program, although at least one is in a park museum collection. Some of Weber's paintings are on display in hallways and offices of the Department of the Interior in Washington, DC.

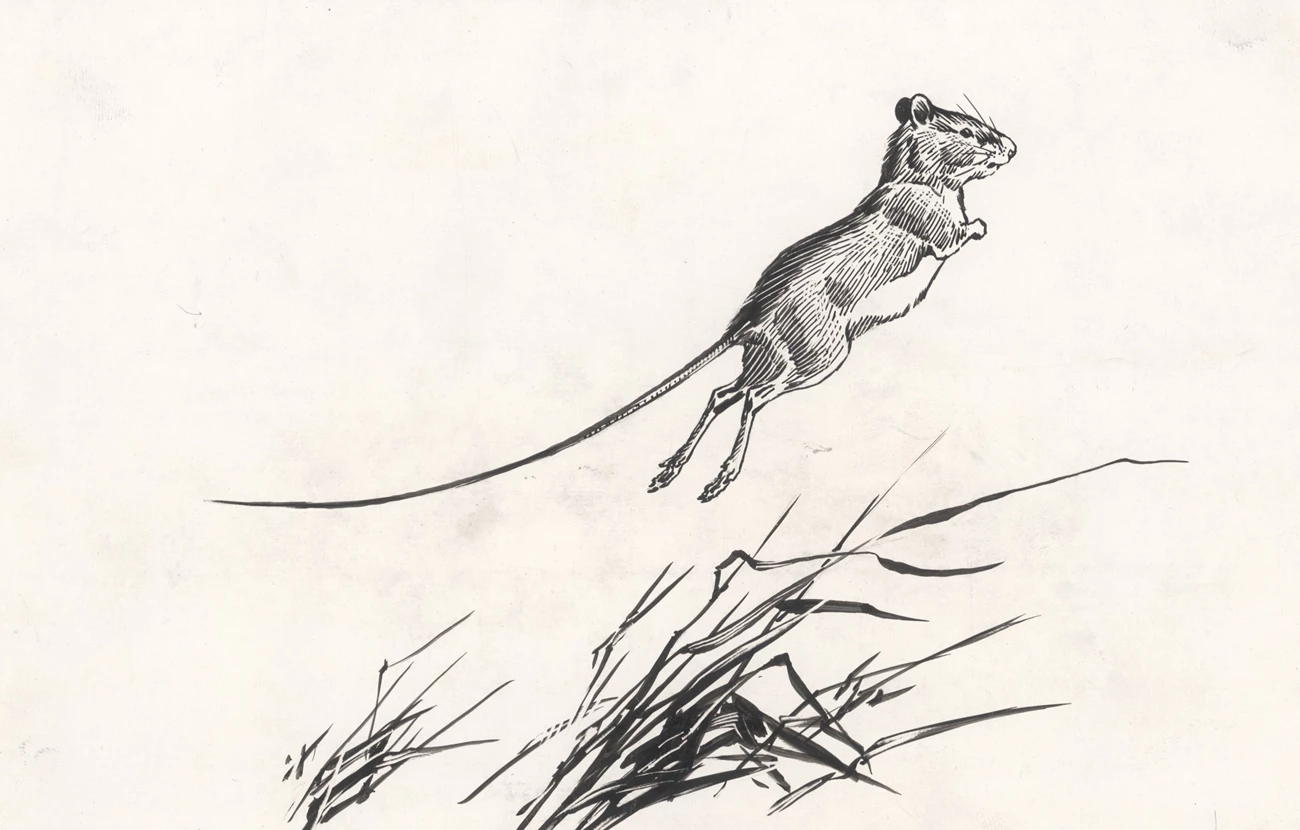

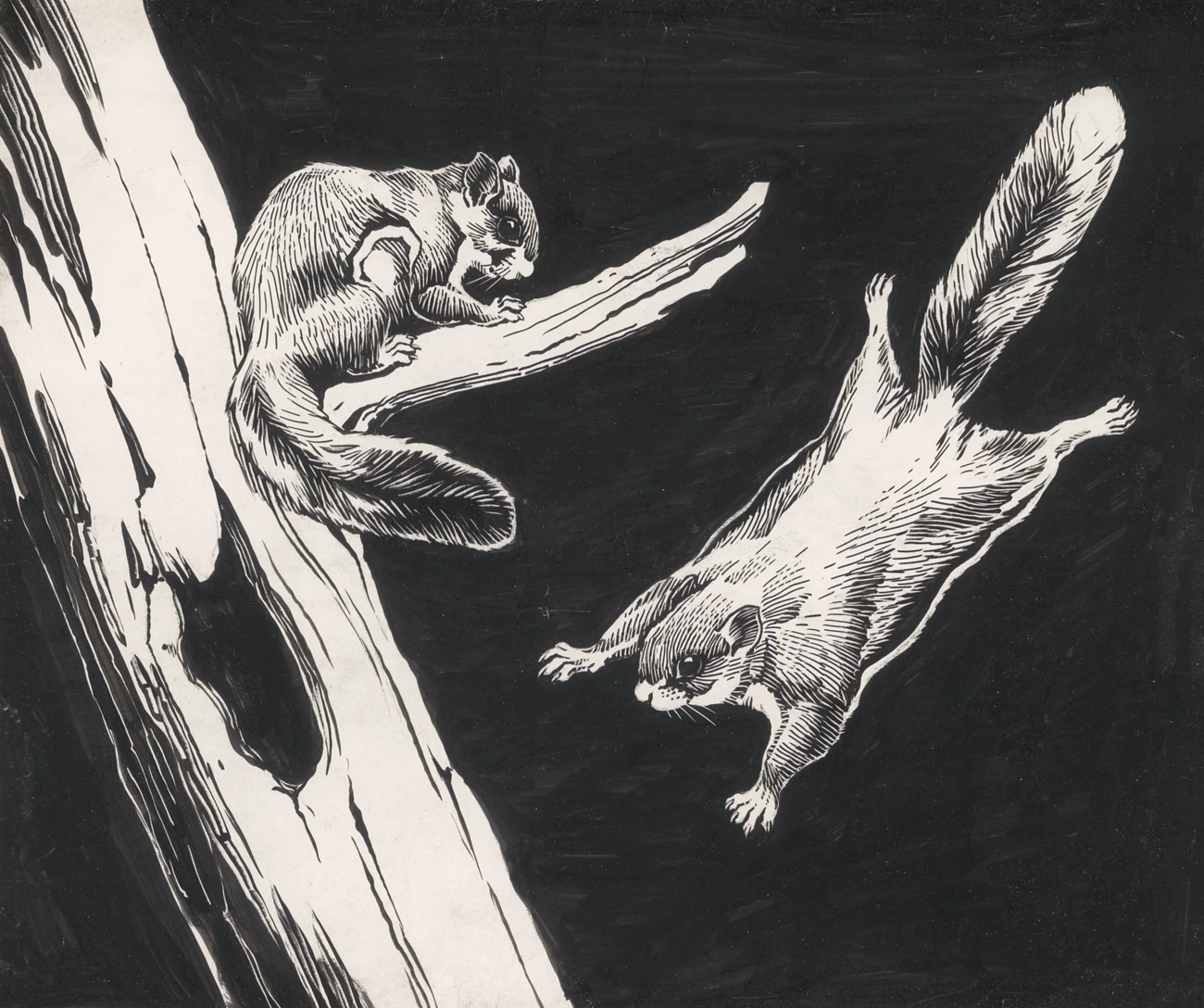

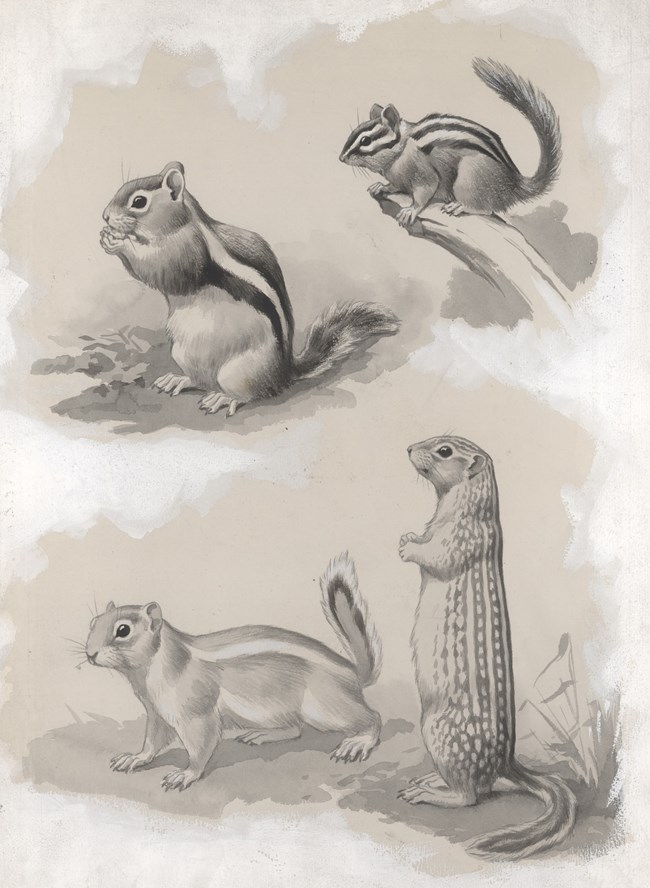

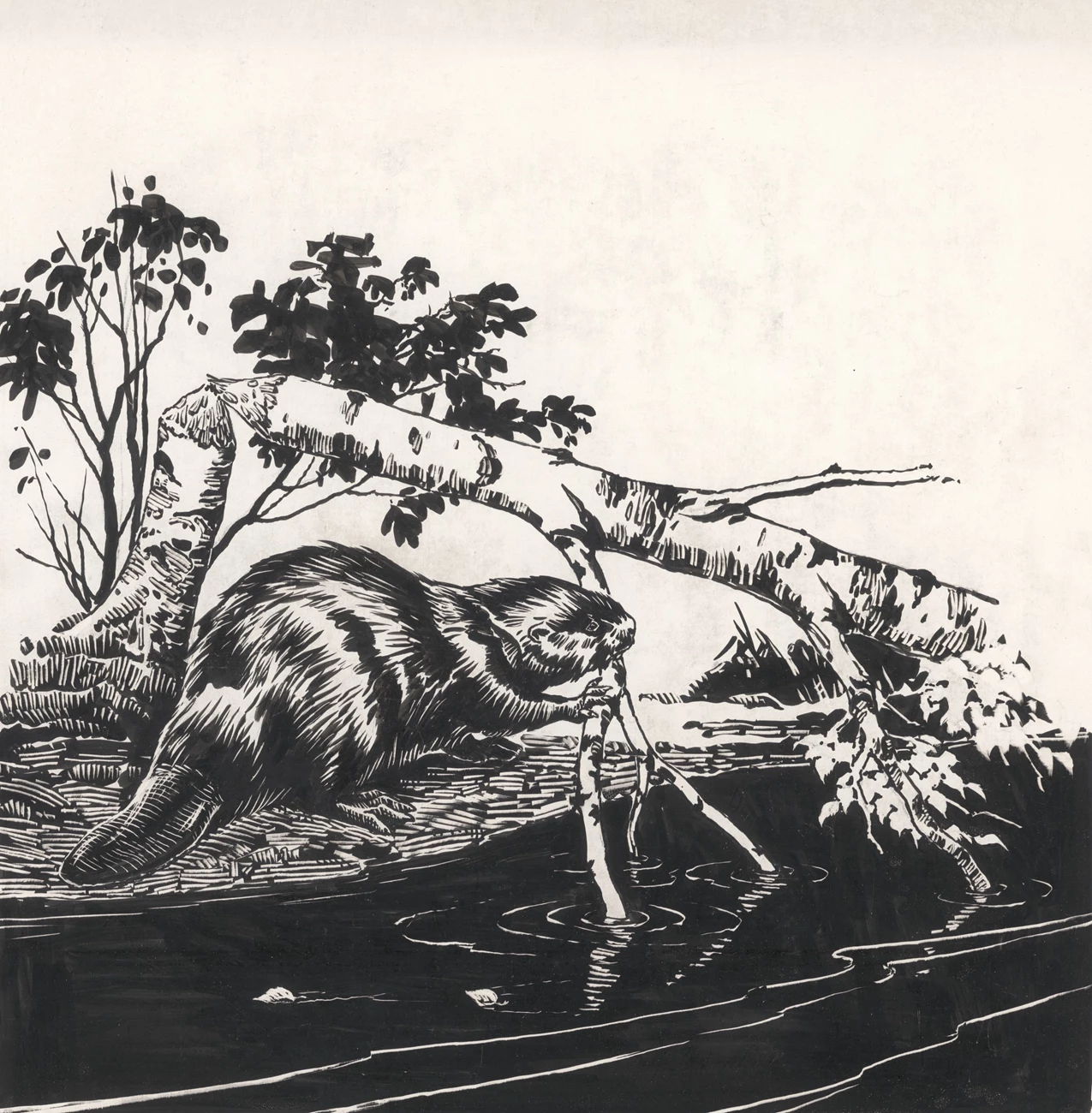

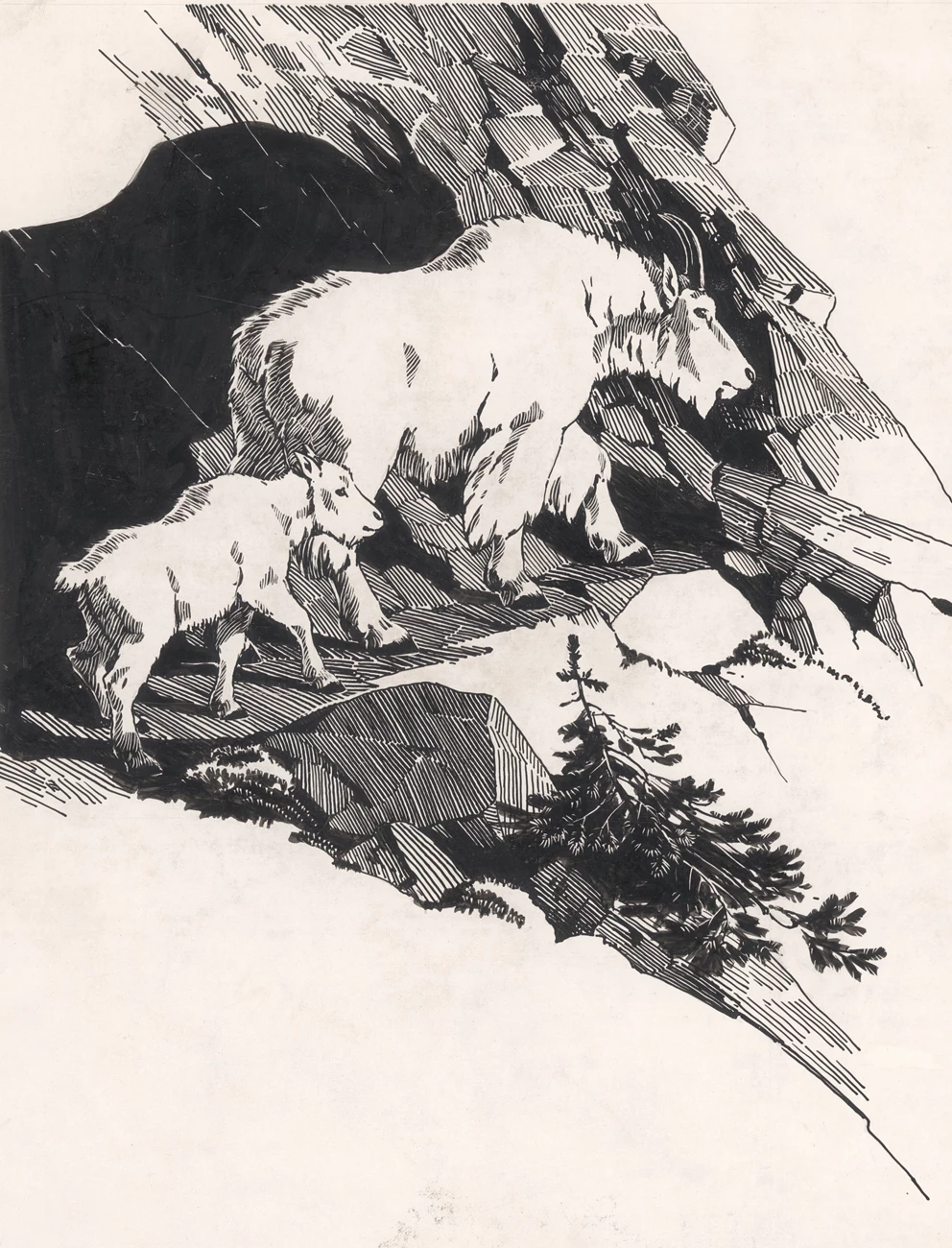

Weber also drew 52 animal species for another book project. Similar to the original intent of Fading Trails, Meeting the Mammals accompanied Weber’s illustrations with a few paragraphs or a page of text about the species. The text was prepared by Victor H. Cahalane, in charge of the section on national park wildlife for the US Fish and Wildlife Service. The book was published in 1943, after Weber left the NPS. The NPS History Collection has 39 of the Meet the Mammals drawings, featuring 56 species. His work isn't just technically accurate. As these examples from the NPS History Collection demonstrate, it is expressive and embodies the characters, habitats, and movements of the animals.

As the war progressed and more offices were needed for the war effort, the NPS moved its offices to Chicago in August 1942. Having just built a house, Weber resigned from the NPS rather than move. He took a job with the Smithsonian Institution as an ornithologist. For the next for two years, he put the bird collection into taxonomic order, verified catalog data, and repaired specimens as needed. Although some authors report that he was the curator of ornithology, Weber described his time at the Smithsonian this way: “I was just a flunky.”

Weber began doing contract work for National Geographic Society (NGS) in 1939. He continued to take contracts from them until 1949. He also did commissions for others during this period. He drew the illustration of three white-fronted geese for the 1944–45 “duck stamp,” an annual federal migratory bird stamp hunters are required to purchase. His design of two trumpeter swans flying over Red Rock Lakes National Wildlife Refuge was selected for the 1950–51 duck stamp. Weber was the first artist to have his work selected for two duck stamps. His trumpeter swan image was also the first stamp to illustrate a species that was protected from hunting.

In January 1950 Weber joined NGS as an employee. Although one of the conditions of his employment was that he wouldn’t work for anyone else, Weber was able to do private commissions that didn’t involve publications. Some of his paintings, however, were published in the June 1950 edition of Ideals magazine. One of his first projects for the society was about wildlife that can be seen from main highways across the country, most in national parks.

He described his artist process, noting, “Getting ready for the type of painting I do generally takes considerably longer than actually doing it. You can safely say that I spend about one-fourth of my time painting and three-fourths in research and study.” He had a collection of over 1,600 bird specimens to study for his paintings. He sometimes used his dog, pet skunks, or even a pet monkey (adopted during a trip to French Equatorial Africa) as models for his art.

Working for NGS, Weber traveled to Africa, South America, Asia, Alaska, and other remote parts of the United States. He illustrated projects like “deer of the world” or “cats of the world.” He created others for “the dog book” and “the fish book.” He illustrated two articles on state trees, which again intersected with national parks. In 1953 he was honored with a one-man show featuring 200 of his watercolors. One of his paintings done for NGS, featuring an eagle about to steal a fish from another bird, inspired the eagle patch for the Apollo 11 mission. NGS and NPS presented a joint exhibition of Weber's paintings for the NPS 50th anniversary. The next year, the Department of the Interior presented its Conservation Award to Weber for the role his "splendid and recognized artistry" had played in inspiring "a wider interest in our native wildlife."

In his oral history interview Weber noted, NGS had “quite a number of my paintings they’ve never published at all…Even if they didn’t use all the work I did, why I had a good time going after it.” Changing technology and decisions by one editor who “didn’t want anything painted that you could photograph,” led Weber to retire in 1971. He donated his large specimen collection to Sweet Briar College, a women’s college in Virginia.

Remembering his time with the NPS, Weber recalled, “Even though we were poor at the time, I think the couple of years I spent making the paintings for Fading Trails were the most pleasant years I spent in my life. I was all by myself. I was pretty well hidden. Nobody told me, ‘Now we want it painted this way.’ And that’s the big contrast to most of the artwork I’ve done in my life. Most of the time somebody’s got some fantastic idea of the way it ought to be.”

Weber died January 10, 1979, in Lynchburg, Virginia. He was 72 years old.

Weber may have sometimes felt like an accidental artist or a frustrated naturalist, but his unique combination of talents, education, and experience created collections of wildlife paintings and illustrations that continue to educate, amuse, and inspire naturalists, artists, and the public.

Sources:

-- (1938, October). “Series of Four Planning Books Approved.” The Regional Review, Vol. 1, No. 4. Accessed on March 25, 2023, at https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/regional_review/vol1-4n.htm

-- (1952, July 29). “Monkey Who Wrestles Skunk Imperils Job as Artist’s Model.” The Evening Star (Washington, DC) p. 20.

-- (1953). “Geographic Society to Exhibit Noted Wildlife Artist’s Work.” The Evening Star (Washington, DC), p. 21.

-- (1979, January 13). “Walter A. Weber, 72, Dies.” The Washington Post. Accessed March 25, 2023, at https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/local/1979/01/13/walter-a-weber-72-dies/f0a8a004-006e-40b7-93c1-81389d515c4d/

Cahalane, Victor H. (1943). Meeting the Mammals. The MacMillan Company, New York.

Elliott, Charles, ed. (1942). Fading Trails: The Story of Endangered American Wildlife. The MacMillan Company, New York.

Evison, Herbert S. (1978, September). “Walter Weber Decorated Interior.” Courier: The National Park Service Newsletter, Vol. 1, No 11, p. 11.

Assembled Historic Records of the NPS (HFCA 1645), NPS History Collection, Harpers Ferry, WV.

Moyer, William J. (1953, July 5). “Hunter with a Brush.” The Evening Star (Washington, DC), p. 21.

Rhody, Jim. (1950, August 30). “New Duck Stamp.” The Freedom Call (Freedom, Oklahoma), p. 2.

Somerville, Clive. (2019, July 15). "Apollo Mission Patches: Badges of Honour." BBC Science Focus. Accessed March 27, 2023, at https://www.sciencefocus.com/space/apollo-mission-patches-badges-of-honour/

Tucker, W.C. (1944, July 20). “Top O’ the Morn.” The Columbus Enquirer (Columbus, Georgia), p. 6.

Weber, Walter (1971, February 25). Oral history interview with S. Herbert Evison. NPS Oral History Collection (HFCA 1817), NPS History Collection, Harpers Ferry, WV.