Part of a series of articles titled Pittsburgh, PA, WWII Heritage City Lessons.

Article

(H)our History Lesson: African American Contributions on the Home Front in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, WWII Heritage City

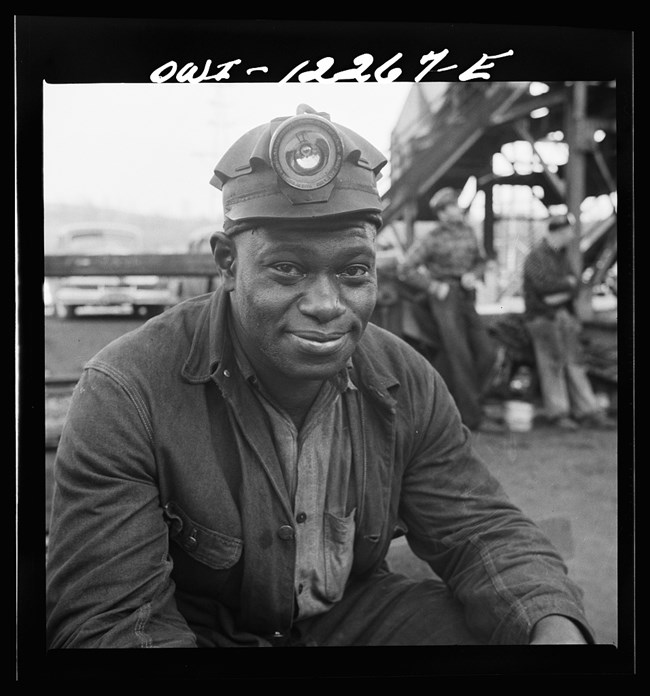

Collier, John, Jr; Library of Congress

About this Lesson

This lesson is part of a series teaching about the World War II home front, with Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania designated as an American World War II Heritage City. The lesson contains photographs, a background reading, and newspaper excerpts to contribute to learners’ understandings about the experiences and contributions of African Americans on the home front in Pittsburgh. It examines discrimination faced and the impacts of the Double V campaign from the Pittsburgh Courier. Extension activities include documentaries on the Pittsburgh Courier and the culture of Wylie Avenue (Hill district) and examining the Pittsburgh Courier’s coverage of Jewish rights.

Explore more lessons about World War II at Teaching with Historic Places.

Objectives:

-

Describe experiences of African Americans in Pittsburgh on the home front.

-

Identify contributions of African Americans in Pittsburgh to the war effort.

-

Explain how the contributions of African Americans to the war effort helped to challenge racism and discrimination.

-

Discuss the significance of the Double V campaign in the history of civil rights in the United States.

Materials for Students:

-

Photos 1 - 7 (can be displayed digitally)

-

Readings 1, 2, 3 (one secondary; two primary)

-

Recommended: Map of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

-

Optional Extension materials 1) documentary links, 2) primary reading

Getting Started: Essential Question

How did African Americans in Pittsburgh contribute to the home front efforts and the civil rights movement?

By the numbers:

-

Pittsburgh’s African American population in the 1940s grew from 62,000 to 86,000 (plus surrounding mill towns). This increase was seen in African Americans composing 8.2% of Pittsburgh’s population in the 1930 census, to about 12% in the 1950 census. In the same time period, the city’s population growth rate overall was +1.4% from 1930 to 1950.

-

75 cents per hour: paid rate advertised for furnace men in a Pittsburgh Courier ad, 1943 (Duquesne Smelting Corporation). This is worth $17.39 today, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics Consumer Price Index (CPI).

Quotation to consider:

“The ‘Double V’ emblem of The Courier has struck me very forcefully. It is of great significance to us as a race and should impress the world with the goals we have set. Every Negro should have some emblem to wear. This Double ‘V’ means more to us than the ‘Buy a Stamp’ or ‘Buy a Bond’ drive!” - Willa Smith, in letter to the editor; The Pittsburgh Courier, March 14, 1942; p. 12

Read to Connect

African American Living and work on the Home Front in Pittsburgh, PA

By Sarah Nestor Lane

African Americans migrated to the Pittsburgh area for employment. This was both before and during the US entry to the war. A 3,000-unit housing project, Terrace Village, opened in 1940 in the “Hill District.” Hill District residents, including those at Terrace Village, included 40 percent white residents.

Many African American businesses were thriving in the Hill district of Pittsburgh in the 1940s. The Hill was unique. It was interracial, unlike downtown Pittsburgh and other neighborhoods. Jewish businesses also thrived in the Hill. The businesses included cleaners, tailors, printing, shops, restaurants, and a hotel. There were dance halls and night clubs, and jazz music flourished. Many businesses were on Wylie Avenue, the main commercial avenue. An annual parade celebrated local businesses and organizations.

The Pittsburgh Courier started as a small African American weekly newspaper. It was first printed for the Hill district neighborhood. It grew into the largest African American weekly newspaper in the country. The Courier worked to expose discrimination. The Courier reported there was massive non-compliance with Pennsylvania’s laws on nondiscrimination. They reported on segregated bathrooms at worksites, automobile clubs, and more. The Pittsburgh Interracial Action Council also protested segregation. They hosted an interracial picnic at a historically white-only pool. This was one of the Council’s many attacks on segregated areas that led to progress over time.

Home Front Contributions

African American residents of Pittsburgh played a crucial role on the home front. They contributed to the war effort in various ways but faced discrimination and segregation.

President Roosevelt issued Executive Order 8802 in 1941. It stated, "There shall be no discrimination in the employment of workers in defense industries and in Government, because of race, creed, color, or national origin." The order led to more African American workers in the defense industries. However, it did not fully prevent discrimination in the workplace.

Many African Americans contributed to the war effort by working in mills and factories, such as the city's thriving steel industry. Pittsburgh, nicknamed the "Steel City," produced steel critical for manufacturing weapons and equipment. African American workers filled jobs that contributed to the production of tanks, ships, and other essential materials. Another example of a workplace that hired African American workers was a grease plant. African American men also worked in mining. Coal mining helped produce energy to fuel wartime distribution and movement. African American workers were usually still paid less and offered less desirable jobs. These jobs often had increased health risks, such as harmful gas exposure.

African American women also worked and served, even with limited opportunities. These women were mostly segregated in their work and limited to opportunities in areas such as cleaning. More working opportunities for African American women were in the Hill district. They also volunteered, such as supporting selling war bonds and drives.

Double V Campaign

African Americans faced racial discrimination, despite their contributions and service at home and overseas. This led to the “Double V” campaign. The “Double V” campaign started from a letter submitted to the Pittsburgh Courier by James G. Thompson. Part of his letter asked, “Should I sacrifice to live half-American?” From this letter came the “Double V,” which stood for victory over two things. First was victory against the Axis powers in the war and second was victory over racial discrimination at home in the United States. Black newspapers and civil rights leaders promoted this idea. African Americans supported the war effort while also fighting for their rights and equality on the home front. The campaign spread nationwide from the Pittsburgh Courier. Pins, clubs, hats, and more for the Double V campaign spread. This was a way for Black Americans to demand the freedoms they were fighting for overseas should extend to them in their own country.

African American residents of Pittsburgh made significant contributions to the war effort. They did so despite facing discrimination and segregation on the home front. Their resilience not only helped win the war but also laid the foundation for important changes in American society.

Teacher Tip: Discuss how the text uses historical language and labels that are not used today to describe the race or abilities of individuals.

Poor Distribution Held Actual Cause of Labor Shortage

Top WMC Official Reports Many Plants Still Refuse to Employ Women, Negroes, or Physically Handicapped; McNutt Asks Removal of Barriers

October 19, 1942, The Pittsburgh Press, p. 4

Washington, Oct. 19 – A top official of the War Manpower Commission reported today that the so-called man-power crisis has developed because of ‘mal-distribution, rather than an actual shortage of workers.” Many of this country’s problems have been aggravated by employers and labor unions “who still act as if this were a peacetime labor market,” he asserted.

Bans Still in Effect

This official – who declined to be quoted directly reported many war plants still refuse to hire Negroes, women, aged, or physically-handicapped workers, despite the serious labor shortages that exist in the same localities.

He added that numerous industries are not co-operating with WMC pleas that they step up their training programs. Shortages in nearly 150 skilled work categories already are so acute that the only way they can be obtained is by training unskilled workers, he said.

‘Some plants which still refuse to hire women could replace 30 or 40 per cent of their workers with women” he said. He mentioned specifically several well-known war plants which still discriminate against Negroes. . . .

WMC Chairman Paul V. McNutt just last night announced WMC’s first ‘statement of policy’ regarding women workers. It urged removal of all barriers against women workers, that they be hired and trained ‘on a basis of equality with men,’ and that they be given ‘free access to foreman’s supervisory and technical jobs.’

It urged employers ‘to analyze all jobs to determine which can be filled by women and to prepare for employing the largest possible number.’

Contributing to Problem

Mr. McNutt listed the following reasons why America’s manpower problems have developed.

-

War contracts have been let too liberally in labor shortage areas. WPB Chairman Donald M. Nelson ordered recently that future contracts be let wherever possible in labor surplus regions, if equipment and other facilities are available.

-

Employers have disrupted Federal efforts to stabilize the manpower front by ‘pirating’ workers from other plants and ‘hoarding’ other workers in anticipation of future needs. This situation has been aggravated further by worker migrations to better paying jobs.

-

Recruiting campaigns have led many badly needed skilled workers to enlist. Selective Service boards often have refused to defer such workers despite careful instructions from Washington.

-

Employers often are refusing to hire women, Negroes, the aged, and the physically-handicapped because of pre-war employment standards and ‘pure prejudice.’

-

And finally because ‘we’re not getting enough production out of the workers already in war jobs.’

The WMC official estimated that ‘if we could increase labor’s production capacity by 20 per cent, we could more than offset the drain on the labor force to be caused between now and December, 1943, if the Army reaches its goal of 7,500,000 men by that time.’

Excerpt from “The Double V Campaign / The Women’s Army”

in the Pittsburgh Courier, March 28, 1942, p. 6

Among Negroes there is the greatest unanimity in history about the Pittsburgh Courier’s Double V campaign – Victory for Democracy at home and abroad.

From the Atlantic to the Pacific, from Canada to Cuba, men women and children are stirred as never before by this slogan which sums up so succinctly the goal of all Americans of good will.

Every person who possesses one of the Double V pins will wear it proudly and prominently, and every person who sees one will know exactly what it means.

This is not a campaign waged by colored citizens alone; it is a campaign waged by all citizens, regardless of color.

Every thoughtful American realizes that the independence of this nation depends upon victory for our armies against the forces of totalitarianism abroad on a dozen fronts.

It is widely understood that at home democracy may perish unless every one of us is unusually vigilant.

If we are to have no democracy at home, it does not make a great deal of difference what happens abroad.

Victory for Democracy abroad means beating the armies of Hitler, Mussolini and The Mikado.

Victory for democracy at home means beating disfranchisement, racial pollution laws, residential segregation, economic discrimination based on color, jim-crowism, social and educational inequalities, and all efforts to curtail or abolish the safeguards of the Bill of Rights.

A Double V pin indicates allegiance to these high ideals for which great men have fought and died through the centuries that we might have a measure of freedom today.

Charles “Teenie” Harris; National Museum of African American History and Culture

Student Activities:

Questions for Reading 1 and Photos 1-4

-

What was the significance of the Hill district?

-

What was the Pittsburgh Courier, and what role did it play in the African American community?

-

What were some of the ways that African Americans in Pittsburgh contributed to the war effort?

- What challenges did African Americans in Pittsburgh face during World War II? How did the Double V campaign confront the challenges?

Questions for Reading 2

-

What is the main point of the article?

-

What are some of the reasons why the War Manpower Commission says there is a manpower crisis?

-

What are some of the solutions that the War Manpower Commission proposes to address the manpower crisis?

- President Roosevelt issued Executive Order 8802 in 1941. It stated, "There shall be no discrimination in the employment of workers in defense industries and in Government, because of race, creed, color, or national origin." This newspaper article was printed in October 1942. What does the article show about the progress against wrongful discrimination?

Questions for Reading 3, Photos

-

What is the symbolic meaning of wearing Double V pins?

-

What does the author mean by "democracy may perish unless every one of us is unusually vigilant"?

-

Explain how the Double V campaign was a response to the challenges faced by African Americans in the United States during World War II.

Extension Activities

The following documentaries connect to the readings in the lesson, and could be watched in part or full:

-

The Pittsburgh History Series: The Wylie Avenue Days (1:01:11, American Archive of Public Broadcasting

Pittsburgh had, and continues to have, a large Jewish community. In The Jewish Community of Pittsburgh, December, 1938: A Small Study, by Dr. Maurice Taylor, it was reported that there were 22,000 Jewish-identifying persons (41% of the Pittsburgh Jewish population) living in the Squirrel Hill District (separate from the Hill District), and 11,000 in the Hill district (mentioned in Reading 1).

The Pittsburgh Courier published several stories and coverage supporting the Jewish population abroad and, in the US. These were both local to Pittsburgh and national publications.

Read the following excerpts from a Pittsburgh Courier article with students and compare this writing to the purpose of the Double V campaign. Additionally, the Jewish population in Pittsburgh offers a rich history that can be explored with students using the oral history collection by the University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh and Beyond: The Experience of the Jewish Community.

Note: Some historical language must be addressed with students as now culturally insensitive and should not be used today.

Anti-Semitism Spreads: Jewish Problem Similar to Ours (excerpts)

By Marjorie McKenzie, Pittsburgh Courier Columnist

October 30, 1943 (p.1, 4)

Washington, D.C. -- It requires considerable self-control for a Negro to read about the anti-Jewish riots in Boston and refrain from I-told-you-so attitudes. Nothing but great objectivity and tolerant understanding of the basis of their own problems can keep Negroes from feeling a fierce satisfaction over the accuracy of their warnings regarding the war-time mushrooming of American prejudices. For they know that a nation that learns to make a scapegoat of Negroes has learned, above all else, to hate, and eventually will lust for more than one victim.

Into the maw of America’s hate are sucked all weak and defenseless minorities – Negroes, Jews, Mexicans, Chinese-Americans, Jap-Americans, and aliens—until gorged and stupid from its own avarice, our country risks the danger of becoming the ludicrous world figure that Germany is today. The Negro press and Negro organizations have been saying this for years: they have advocated the Negro’s cause, not on a narrow group basis, but in terms of preserving the American ideal—by making of the Negro a symbol of a democracy at the cross-roads rather than a special pleader. ….

Must Combine Strength

There are always such measurements as skin color and hair types and other differences which science has recorded and catalogued. To refuse to recognize them is comparable to sticking one’s head in the sand. It seems simpler to conquer one’s fear of the stranger, to accept him as different but equal to oneself. It is the very dissimilarities among people which enrich and embroider the culture.

The time has come when, if we wish to preserve ourselves—Jew and Negro and Mexican – as well as our integrity, which is indeed the honesty and soundness of America herself, we must combine our strengths and fight together for a future which we have a right to share with our white, Christian brother.

Additional Resources

A Day at the Grease Plant (placesjournal.org)

Double Victory | National Museum of African American History and Culture (si.edu)

The Double V Victory | The National WWII Museum | New Orleans (nationalww2museum.org)

"The Good Fight" Documentary (28:01) | History Documentaries | WQED

This lesson was written by Sarah Nestor Lane, an educator and consultant with the Cultural Resources Office of Interpretation and Education, funded by the National Council on Public History's cooperative agreement with the National Park Service.

Tags

- world war ii

- world war 2

- wwii

- ww2

- world war ii home front

- wwii home front

- home front

- pittsburgh

- pennsylvania

- teaching with historic places

- twhp

- twhplp

- hour history lessons

- awwiihc

- american world war ii heritage city program

- african american history

- wwii aah

- african american world war 2

- african americans in wwii

- military history

- military and wartime history

- wartime production

- african american women

Last updated: February 2, 2024