Last updated: March 1, 2022

Article

“A New Attraction”

States licensed women hunting and fishing guides as early as the 1890s, but in national parks the emphasis was on nature study and tours for visitors. It's commonly thought that the Rocky Mountain National Park was the first park to license women guides in 1917, but there was at least one licensed woman guide working at Glacier National Park four years earlier.

Mamie Henkel Burns: The First NPS-Licensed Woman Guide

Glacier National Park was established in 1910. Guides operated under concession permits there as early as 1911. The superintendent’s ability to “grant authority to competent persons to act as guides and revoke the same at his discretion” was added to the park’s general regulations by March 30, 1912. Newspaper accounts from that year document that licensed guides were “operating under the supervision of the superintendent of the park.” Guides provided horses and led horseback parties on tours for an authorized charge.

Mamie “Mae” Henkel Burns was one of the first three guides qualified under this new authority in 1913. The gender and identity of the other two guides are unknown. A 1913 article in Chicago’s The Inter Ocean reports, however, that “Some of the Indians even have become licensed guides and escort parties through the preserve,” suggesting that she was not the only Native American guide.

Mae Henkel was born in Shonkin, Montana, on August 27, 1888. She was a member of the Blackfeet tribe. Before marriage, she had her own string of ponies which she used to deliver supplies throughout the area. She married William Burns and they went into business together.

William Burns was granted a concession permit in 1913 for “five horses, saddle and pack transportation.” The NPS as a bureau didn't exist until 1916 and the permit was issued by the Department of Interior, at an annual cost to Burns of $5. Mae Burns would have been licensed by the superintendent as a guide for that family venture.

The business did well and in 1915 Burns' permit was renewed for 10 horses at a cost of $10. New conditions were added in writing to the permit that year. One provided that the superintendent would inspect the stock and equipment used under the permit. Another required "All persons employed as guides under this permit shall have a license from the superintendent of the park."

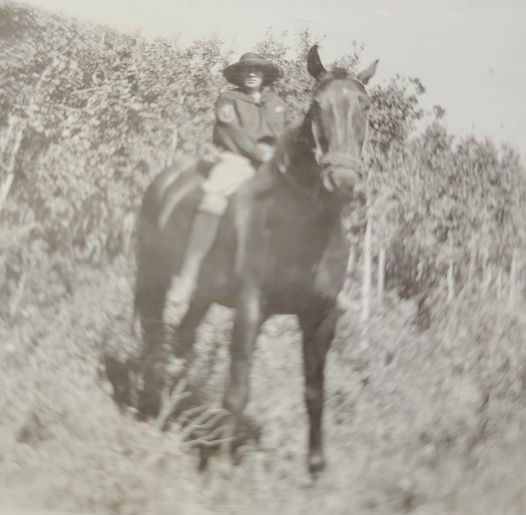

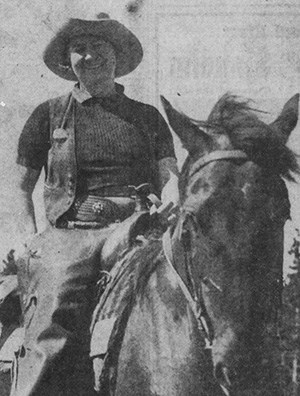

Although Glacier issued badges to its licensed guides, none of the surviving examples in the park's museum collection are this early. A photograph of Mae Burns on her horse "Peaches" from her family collection appears to show her wearing a badge. She wears typical riding clothes of the era, including breeches, a middy blouse, and a broad-brimmed hat. She appears to have a patch on her right sleeve.

Mae Burns probably guided just three or four seasons. Her husband only received permits from 1913 to 1916. She may have stopped guiding by 1916 when she gave birth to her son and at about the same time a settlement of two dozen cows and calves from her family likely made ranching an alternative to guiding.

When the US Reclamation Service condemned the Henkel family ranch to create a reservoir in 1918, Burns received an allotment on the Blackfeet Reservation. Her husband died in 1923, and she lost her eyesight to glaucoma in 1927 when she was just 39. In the 1930s she leased part of her allotment for income. When an oil boom came to the reservation in the mid-1950s, she received a lease bid that also provided an income. She died in 1972.

Mamie Burns rightfully holds the distinction of being the first NPS-licensed women guide, one traditionally given to sisters Elizabeth and Esther Burnell. Although the Burnell sisters are better known, it turns out that they weren’t the first licensed women guides at Rocky Mountain National Park either.

The Forgotten “Nature Guards”

Rocky Mountain National Park Superintendent L. Claude Way chose “cultured college girls” as that park’s first licensed women guides in 1917. The “nature guards,” as the Denver Post called them, were licensed “to comply with innumerable requests upon the part of Eastern tourists for such a service.” Another newspaper noted that “women are to have an equal chance with the men as guides in the Rocky Mountain National Park.”

To earn their licenses, the women had to pass the “rigid federal examination” created by Way. The July 13, 1917, Denver Post article records that Lydia Bragstad, Hazel Davis, Ellen M. Knowles, and Edna Knowles—not the Burnell sisters—were the first to complete the licensing requirements. Upon their licensing, Way noted, “Few men could qualify so well as lecturers on nature subjects."

Raised in the Rockies, these “exceptionally intelligent college girls” accompanied camping parties and lectured about the park’s plants and animal life. Tourists paid a small fee to hire the women guides, but the NPS made their services available through the park’s administrative office in Estes Park. The popularity of these women guides was remarked upon in syndicated newspaper columns that noted “almost from the hour that their appointments were announced they have been swamped with applications for their services.”

Little is known about these women beyond what was recorded in the newspapers. Although Way’s description of the licensed women guides as “a new attraction” made it into the 1917 NPS director’s annual report, their names did not. That omission likely led to the four women being overlooked in early NPS history, leaving the well-known Burnell sisters to fill the void.

Guiding Sisters

Kansans Esther A. and Elizabeth F. Burnell were also college-educated women. They visited Rocky Mountain National Park as tourists in 1916. Esther decided to stay and homesteaded in the Estes Park area. In 1918 she became famous for crossing the Continental Divide alone. She met conservationist, photographer, hotelier, and nature guide Enos A. Mills and became his secretary at his Longs Peak Inn.

Mills saw nature guiding as “a good profession for women” and encouraged the sisters to take the Rocky Mountain National Park guiding exam. Working as guides for Mills at his Longs Peak Inn, Esther is traditionally credited as the first licensed woman guide in the NPS, followed shortly by Elizabeth. However, the evidence points to the Burnell sisters as licensed guides in 1918, not 1917. As demonstrated above, there were at least five other NPS-licensed women guides before them.

Whereas Bragstad, Davis, and the Knowles are featured in the 1917 newspaper article that describes them as the first licensed guides, the earliest articles about the Burnell sisters are from 1918. A July 4, 1918, report in the Des Moines Tribune describes Esther’s solo crossing of the Continental Divide at the start of the 1918 season, noting that “she is now an authorized nature guide” at the park, suggesting she was licensed by July of that year. More conclusively, an August 14, 1918, article in The Chicago Tribune announcing Esther’s marriage to Mills states, “She qualified this summer as a licensed nature guide in Rocky Mountain National Park.” Elizabeth Burnell is also described as “an accredited guide” in articles discussing her sister’s wedding. Both, it would seem, were licensed in 1918, not 1917 as previously believed.

Esther married Mills in August 1918 in Boulder, Colorado. Their daughter Enda was born the next year. Mills died in 1922. Esther Mills continued to run the Longs Peak Inn until she sold it in 1946. She died in 1964.

Elizabeth continued seasonal guiding in the park for several years, at least through 1924. In 1919 she was described as wearing a “regulation feminine outing costume” of khaki trousers and a coat. A 1920 newspaper article described her clothes as a “climbing costume.” At that time, Burnell stated that to qualify as a nature guide, a woman must have “knowledge of geology, botany, natural history, and first aid. She must know the roads and trails of the country where she works, and should be able to manage horses, pack them, make camp, and cook.” She also expressed her belief that “It should not be necessary to take a man along,” noting that she had “camped absolutely alone for a week at a time and wandered around Mt. Long alone at night.”

Superintendent Way limited the women guides to working below the tree line, but Elizabeth frequently broke that rule. She was a strong advocate for nature guiding and worked as a nature study supervisor in the Los Angeles city schools. She married Norman Smith in Los Angeles in 1933. Elizabeth Burnell Smith died in April 1960 at Denver, Colorado.

“The Regalia of the Frail Form of Woman”

Following the success at Rocky Mountain National Park, women guides began at Mount Rainier National Park in 1918. Trained by Professor O.B. Sperlin of Stadium High School in Tacoma, Washington, and manager of the guide service for Rainier National Park Company, the women “met and personally conducted” tourists on expeditions throughout the park. Newspaper accounts at the time don’t name the women or give definitive numbers but noted that “besides being experts in the lore of the woods and mountains, of rocks and rills, of glaciers and crevasses, they are skilled mountaineers."

The 1918 NPS director’s annual report is less poetic but reported “Trail trips were under the efficient guidance of trained mountaineers, one or two of whom were women…Guides, principally women, were also employed to conduct studies of the wild flowers and other plant life while making short walking trips from the hotel and camps in Paradise Valley.” Notably the director’s report doesn’t mention Helene Wilson, the first woman ranger at Mount Rainier (and the second in the NPS) who worked from July 1 to September 4 that same year.

Although accounts refer to “women guides,” only Alma Dorthea Wagen is remembered by name today. She was born in Mankato, Minnesota, on November 5, 1878. A graduate of the University of Minnesota, she moved to Tacoma in 1903. One newspaper article reported that she offered her mountain guide services to the government in 1918 when men were in short supply due to World War I. Interestingly that war also provided opportunities for Wilson and Clare Marie Hodges to work as park rangers (see Rangers, Not Rangerettes).

In 1918 Wagen was a 40-year old German teacher at Stadium High, where she would have known Sperlin. Although she later went on to teach mathematics at the school, each summer she guided tourists to Nisqually Glacier and the top of Pinnacle Peak and Mount Rainier. In 1921 she guided a party through a raging blizzard for a wedding ceremony on the summit of Mt. Rainier.

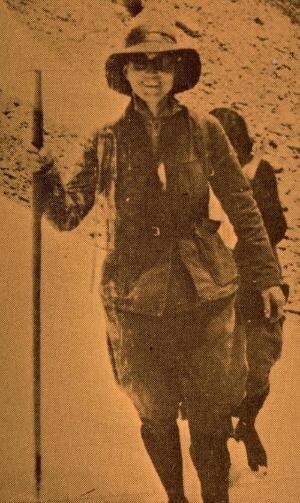

Under the headline “Women to Guide Rainier Park Visitors,” the July 19, 1918, Oregon Daily Journal described the alpenstock, calked boots, ice pick, and lifeline as “parts of the proud regalia of the frail form of woman. Nature guides they are called.” A 1922 newspaper article described Wagen’s “mountain garb” as a khaki shirt and breeches together with “stout knee boots.” Wagen worked at Mount Rainier for at least six seasons. She married Dr. Horace J. Whitacre in 1926 and stopped teaching in the Tacoma schools in 1927. He died in 1944, and she moved to California in 1950. Alma Wagen Whitacre died in 1967, at age 89.

Looking After “The Needs of Women”

Before Mamie Henkel Burns’ position as a licensed guide in 1913 was rediscovered, Gertrude Parmalee Norton was believed to be the first women guide at Glacier National Park. Born January 22, 1875, in Syracuse, New York, around 1900 Norton moved with her sister to East Helena, Montana, where she taught school.

Beginning around 1903 she spent her summers teaching and pursuing her own botanical studies at the Montana biological station on Flathead Lake. Although she moved to Salt Lake City, Utah, with her brother in 1907, she continued to spend her summers at the biological station where she taught and “looked after the needs of women.” She became a recognized botanical authority. In 1910 a new species of St. John’s Wort was named for her.

It’s not surprising the Great Northern Railroad hired her to conduct guided walks and identify plants for visitors at the Many Glacier Hotel. The job coincided with Norton’s return to Montana during the summer of 1919 to visit her sister. She had already planned a trip to the park, and the guiding work may have been an unexpected opportunity since she only worked for a few weeks. Norton quickly became known as the “Flower Lady” around the hotel. If she had any plans to continue the next season, they ended when she died of pneumonia on March 4, 1920, at age 45.

A World Champion Guide

Although a 1923 newspaper account describes Alma Wagen as “America’s only woman guide,” there were others working in national parks. Besides Elizabeth Burnell, there was Bertha Kaepernik Blancett. She was a noted horsewoman, known as “the most famous woman rider in rodeo.” She was the first woman to compete in bronco busting at Cheyenne Frontier Days in 1904. In 1906 she joined Pawnee Bill’s Wild West Show, where she put on exhibitions until she joined the Miller Brothers 101 Ranch Show in 1909.

She married fellow rodeo star Dell Blancett. Together they travelled the Wild West and rodeo circuits in the United States and abroad. They also appeared in a few early Hollywood films. With a rodeo career that spanned over 40 years, she won numerous world championships, including the ladies relay race (1911, 1912, and 1913); ladies bronco busting (1914 and 1915); and ladies Roman race, standing astride a pair of horses (1918). She was widowed in World War I and retired from the rodeo circuit in 1919, although she occasionally worked in the field to raise money.

By 1922 Blancett was the only licensed woman guide at Yosemite National Park. That same year, she was cited for bravery by the park’s superintendent for her quick action upon discovering a fire while leading a party of tourists at the top of Yosemite Falls trail. Quickly unsaddling her horse, she used the saddle blankets to beat out the flames. Using the lid of a nearby trash can, she dug a fire line to prevent spread to nearby trees. Finally, she used the trash can to dump water on the smoldering fire. Although she had help from some of the men in the party, it was her quick thinking and leadership that prevented the fire from spreading.

Blancett was still working as a Yosemite guide in 1924, but it’s uncertain when she retired from her guide career. No photos of her as a park guide have been found. By around 1933 she had left the area. In 1975 she was inducted into the National Cowboy and Western Heritage Hall of Fame. She died in 1979 at age 96 but was posthumously inducted in the National Cowgirl Hall of Fame and Museum in 1999.

Continuing the Tradition

Although the Burnell sisters remain the most famous licensed nature guides at Rocky Mountain National Park, others came after them. In 1920, as the 19th Amendment to the US Constitution became law, Helen Steele Pratt passed the examination and received her Rocky Mountain National Park guide license.

Born January 26, 1883, in Illinois, Pratt became a well-respected nature guide, lecturer, and wildlife photographer. For many years she worked as the nature guide at two camps in the mountains outside of Los Angeles. In 1920 on newspaper article described her as a "trained, professional nature guide."

Pratt was a member of the California Federation of Women’s Clubs and the Los Angeles Audubon Society, which appointed her deputy game warden for LA County in 1918. Regarding her guide license Pratt noted, “They haven’t encouraged women to take this examination. I think our growing importance politically has made the authorities at last grant us recognition in the world of nature too.” She died in 1965 in Los Angeles.

Margaret Roebling also passed the licensing exam at Rocky Mountain National Park. Born in June 1896 near Omaha, Nebraska, she attended the University of Nebraska from 1916 to 1918. In 1919 she became a government “reconstruction aide” in occupational therapy, working with World War I veterans at Fort Snelling, Minnesota. She returned to Nebraska where she taught at Seward High School and later accepted a position at the Omaha School of Commerce.

Roebling became a licensed guide in 1921, working for concession operator Lewis-Byerly Tours of Estes Park. She was one of only three licensed women guides in Rocky Mountain National Park that summer. Elizabeth Burnell was probably the second guide but the identity of the third is unknown. She probably only worked one or two seasons as she went East to study music around 1924. She toured the United States with an opera company before marrying Leo Manville in 1926 in New York City. Margaret Roebling Manville died in 1979 in White Plains, New York.

Glacier National Park also sporadically continued its women guiding tradition. By 1929 Mrs. Ralph Ricard (known as “Mrs. Silver” due to her husband’s prematurely graying hair) was the only registered woman guide at the park. She may have been the first in more than a decade after Mamie Henkel Burns stopped guiding around 1916.

Newspaper accounts describe her “as good a cowboy as her husband.” She lassoed, saddled, and packed her own horses, pitched her own tents, and was an expert at tying knots. With her husband, she also tracked and trapped live mountain lions, selling them to city parks and zoos. As a guide she wore riding clothes typical of the period, including breeches, boots, shirt, kerchief, hat, and gauntlets (gloves). She wore a round badge pinned to her shirt to reflect her official status as a registered guide.

It’s not clear how many seasons Mrs. Ricard worked at Glacier National Park. Indeed, even discovering her given name has not yet been possible.

Almost another decade passed before Florence “Flissy” Rogers Cassill of Seattle, Washington, earned her guide license at Glacier in 1937. Born in the East, her family moved to Montana when her father got a job with the Great Northern Railroad. One unsubstantiated newspaper article reported in 1949 that her mother was the “first woman to hunt and fish in Glacier National Park” (referring of course only to white women).

A September 14, 1937, article in the Great Falls Tribune described Cassill as “the first white woman taken into the Blackfeet tribe and was given the Indian name River Woman.” An article on “Modern Women” in 1940 recalled the same story and noted that she spoke their language. She occasionally lectured about Blackfeet arts and crafts and her guiding experiences at girls schools in the East.

In 1924, the year after she graduated from the University of Washington, she established the Shining Mountain Camp, an “exclusive summer camp for girls.” As the camp grew from its initial three girls, Cassill’s license allowed her to officially guide them on trips into the park. She married Charles Harvey Cassill, Jr. in 1925.

Newspaper accounts in 1938, 1940, and 1941 describe her as the only licensed woman guide in the park. One photo from 1938 shows her in typical horse-riding clothing with a round badge pinned to her vest. That same year she brought 20 “young ladies from coast families” to the park for the summer. She was still guiding young people in the park in 1941. She continued to run the camp for more than 25 years. Little else is known about Cassill.

More Lumberjacks than Guides

Although this research has uncovered stories of more licensed women guides working in national parks than previously known, there weren’t many, and they worked in only a few parks.

Their small numbers are not surprising given that few women worked in this non-traditional field in the early to mid-1900s. According to 1930 census data, there were 87 women hunters, trappers, and guides working throughout the United States. The percentage who were guides (rather than hunters or trappers who could not work in national parks) is unknown. States, a few other federal agencies, dude ranches, and other private guide businesses also hired guides, meaning very few (if any) probably worked in national parks in 1930. In comparison, there were 95 women registered as lumberjacks, rafts women, and wood choppers that year. Another 15 women were foresters or “forest rangers,” with less than a handful known to work for the NPS.

No women guides licensed by the NPS in western national parks have been identified after World War II. Many factors probably play into this, but more study is needed before suggesting reasons. Following WWII, however, the licensed guide model moved east, and two new trends appeared. The late 1940s to early 1970s Girl (Guide) Power sees teenage girls step into licensed or formally trained guide positions in national parks and historic sites. Beginning in the 1950s licensed historical guides become Women on the Battlefield at Vicksburg and later Gettysburg.

Explore More!

To learn more about Women and the NPS Uniform, visit Dressing the Part: A Portfolio of Women's History in the NPS.

This research was made possible in part by a grant from the National Park Foundation.