Last updated: April 12, 2023

Article

"Comfortable Camps?" Archeology of the Confederate Guard Camp at the Florence Stockade (Teaching with Historic Places)

This lesson is part of the National Park Service’s Teaching with Historic Places (TwHP) program.

...the men have constructed for themselves as comfortable camps as circumstances allow, being without plank or nails. Some, who were able, have brought cloth and made themselves tents, in which they can keep dry.

Thomas J.Eccles of the 3rd Battalion, South Carolina State Reserves described the camp of the Confederate guards stationed at the Florence Stockade on November 11, 1864. The guards included a mix of regular Confederate Army troops and South Carolina State Reservists. Eccles wrote a column for a local newspaper during his service as a guard at the Florence Stockade and described many of the aspects of life at the camp.

The Florence Stockade had been constructed in September 1864 in a large field surrounded by dense pine forest and forbidding swamps near Florence, South Carolina. Built on a similar pattern to the prison at Camp Sumter in Andersonville, Georgia, the stockade consisted of a large rectangular opening surrounded by walls built with vertical logs. The prison population peaked at approximately 15,000, and of these, nearly 2,800 died in captivity. The dead were buried in long trenches that formed the nucleus of what is now the Florence National Cemetery Archeological investigations in 2006 revealed a portion of the campground of the Confederate guards. The project area included the remains of at least eight structures, three possible tent stands, three wells, and a large number of latrine trenches, privies, pits, post holes, and other archeological features. Over 5,000 artifacts were recovered, including a wide variety of food and beverage containers, military equipment, camp hardware, and personal items. This material can tell us a great deal about what life was like for the guards at the Florence Stockade.

About This Lesson

This lesson is based on the National Register of Historic Places documentation for “The Stockade” and “Florence National Cemetery,” part of the “Civil War Era National Cemeteries MPS;" and on archival and archeological research sponsored by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, National Cemetery Administration (NCA), conducted by archeologists with MACTEC Engineering and Consulting, Inc. (MACTEC). The lesson was written by Paul G. Avery, RPA, Archeologist with MACTEC, in cooperation with the NCA history staff, as one component of the mitigation associated with the expansion of Florence National Cemetery. It was edited by educator Jim Percoco and the Teaching with Historic Places staff. This lesson is one in a series that brings the important stories of historic places into classrooms across the country.

Where it fits into the curriculum

Topics: The lesson could be used in units on the Civil War, military camp sites, or on prisoners of war. It also demonstrates how the historical record and archeological data are used in combination to provide a clearer understanding of events in the past. Students will develop skills in reading, data synthesis, and analysis from a variety of sources.

Time period: Mid to Late 19th century

United States History Standards for Grades 5-12

“Comfortable Camps?” Archeology of the Confederate Guard Camp at the Florence Stockade relates to the following National Standards for History:

Era 4: Expansion and Reform (1801-1861)

-

Standard 3B- The student understands how the debates over slavery influenced politics and sectionalism.

Era 5: Civil War and Reconstruction (1850-1877)

-

Standard 1A- The student understands how the North and South differed and how politics and ideologies led to the Civil War.

-

Standard 2A- The student understands how the resources of the Union and Confederacy affected the course of the war.

Curriculum Standards for Social Studies

(National Council for the Social Studies)

"Comfortable Camps?" Archeology of the Confederate Guard Camp at the Florence Stockade relates to the following Social Studies Standards:

Theme I: Culture

-

Standard D - The student explains why individuals and groups respond differently to their physical and social environments and/or changes to them on the basis of shared assumptions, values, and beliefs.

Theme II: Time, Continuity, and Change

-

Standard B - The student identifies and uses key concepts such as chronology, causality, change, conflict, and complexity to explain, analyze, and show connections among patterns.

-

Standard D - The student identifies and uses processes important to reconstructing and reinterpreting the past, such as using a variety of sources, providing, validating, and weighing evidence for claims, checking credibility of sources, and searching for causality.

Theme III: People, Places, and Environments

-

Standard A - The student elaborates mental maps of locales, regions, and the world that demonstrate understanding of relative location, direction, size, and shape.

-

Standard D - The student estimates distance, calculates scale, and distinguishes other geographic relationships such as population density and spacial distribution patterns.

-

Standard H - The student examines, interprets, and analyzes physical and cultural patterns and their interactions, such as land uses, settlement patterns, cultural transmission of customs and ideas, and ecosystem changes.

Theme IV: Individual Development & Identity

-

Standard C - The student describes the ways family, gender, ethnicity, nationality, and institutional affiliations contribute to personal identity.

-

Standard D - The student relates such factors as physical endowment and capabilities, learning, motivation, personality, perception, and behavior to individual development.

-

Standard E - The student identifies and describes ways regional, ethnic, and national cultures influence individuals' daily lives.

-

Standard F - The student identifies and describes the influence of perception, attitudes, values, and beliefs on personal identity.

Theme V: Individuals, Groups, and Institutions

-

The student analyzes group and institutional influences on people, events, and elements of culture.

Theme VI: Power, Authority, & Governance

-

Standard C - The student analyzes and explains ideas and governmental mechanisms to meet wants and needs of citizens, regulate territory, manage conflict, and establish order and security.

-

Standard D - The student describes the ways nations and organizations respond to forces of unity and diversity affecting order and security.

-

Standard F - The student explains conditions, actions, and motivations that contribute to conflict and cooperation within and among nations.

Theme X: Civic Ideals and Practices

-

Standard F - The student identifies and explains the roles of formal and informal political actors in influencing and shaping public policy and decision-making.

Objectives for students

- To describe the equipment and supplies available to the guards at the Florence Stockade and the conditions they experienced in their camp.

- To compare and contrast conditions for the prisoners inside the stockade with those of the guards outside its walls.

- To describe the archeological methods used to investigate the campground.

- To discuss how archeological data influences the historical record.

- To compare the experience of women in the Civil War to women who have served in more recent wars.

Materials for students

The materials listed below can either be used directly on the computer or can be printed out, photocopied, and distributed to students. The maps and images appear twice: in a low-resolution version with associated questions and alone in a larger, high-resolution version.

- Two maps of Civil War prisons and the Florence Stockade;

- Three drawings of the plan of the stockade and of a shelter built by prisoners;

- Four readingson the history of Florence Stockade and the archeological excavation;

- Two photographs of artifacts.

Visiting the site

The site of the Florence Stockade is located off of Stockade Drive in Florence, South Carolina. The Friends of the Florence Stockade maintain a gazebo with information on the Stockade and a walking trail that allows visitors to see the existing remains of the Stockade. Visitors can walk where the prisoners were held and see the remains of the earthen wall that held up the posts forming the Stockade as well as the ditch that prevented the prisoners from tunneling out. In addition, the trail leads to several defensive positions manned by the Confederate guards. Further information on the Florence Stockade can be obtained from the Friends of the Florence Stockade by writing to them at 307 King's Place, Hartsville, South Carolina, 29550.

In addition to the Stockade, the graves of the prisoners who died while in captivity are located in the Florence National Cemetery, which is located on National Cemetery Road in Florence, South Carolina. The cemetery consists of two parts, the original tract north of National Cemetery Road and a newer expansion to the south. The cemetery contains the remains of over 9,000 soldiers and their family members who served in every period of peace and major conflict since the Civil War. The burial trenches of the Union prisoners are located in the older portion of the cemetery. The cemetery office is open Monday through Friday from 8 a.m. until 4:30 p.m., but is closed on Federal holidays. The cemetery contains historical markers and is open for visitation during day-light hours year round. The portion of the cemetery discussed in this daily lesson is located south of the main flag pole. For more information on the Florence National Cemetery, contact the office at 803 East National Cemetery Road, Florence, South Carolina, 29506, or visit www.cem.va.gov/CEM/cems/nchp/florence.asp.

Getting Started:

Inquiry Question

Examine the photo carefully.

What kind of place do you think this might be?

Setting the Stage

Civil War historians estimate that from 1861-1865 close to 700,000 Americans died as a result of the American Civil War. Statistically that was 2% of the population of the United States at the time. In 2003, 2% of the population would translate to roughly 6-7 million people.

Most Americans are familiar with names like Gettysburg, Antietam, Vicksburg, and Shiloh - sites of horrific battle carnage. It’s these places, whose names are often in bold in secondary school textbooks that reflect what we know or think about the Civil War. Yet out of the total number of deaths in the Civil War, 56,000 Americans perished in Civil War prisons north and south of the Mason-Dixon Line. Untold numbers of others had their lives permanently altered bearing the physical, psychological, and emotional trauma of enduring time in these camps.

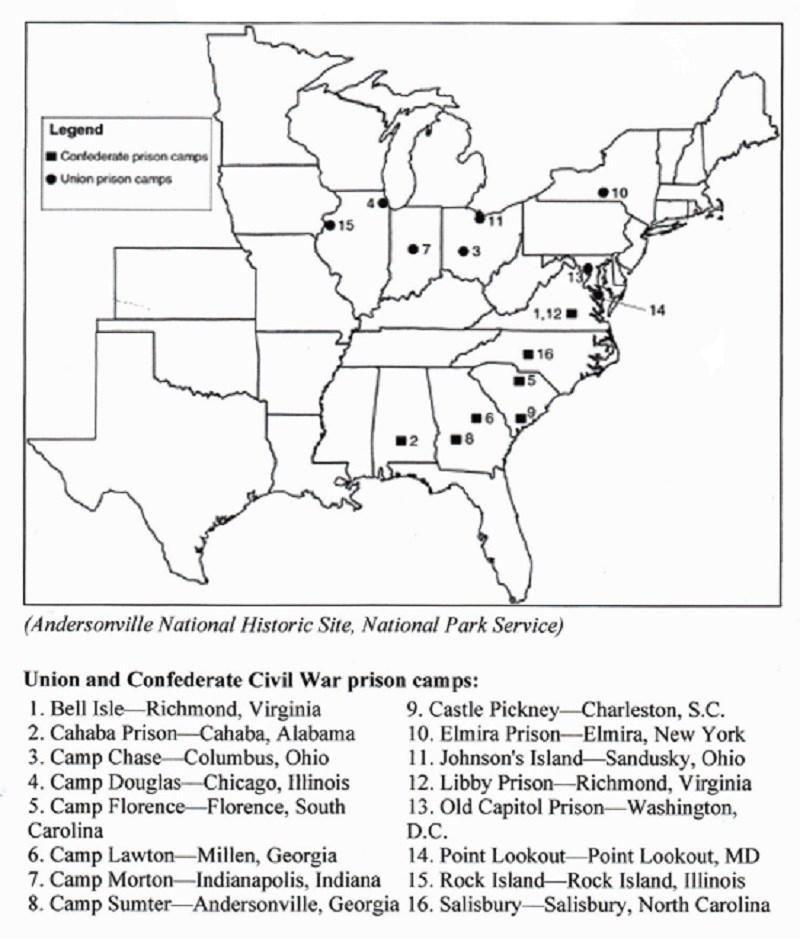

While many may recognize the name Andersonville as the most notorious of the Civil War prison camps there were fifteen other places in the Union and Confederate Camps where prisoners were incarcerated.

When the war began both sides figured that it would be a brief encounter. Neither side was prepared for the catastrophic loss of life and hundreds of thousands of maimed soldiers. After the first battle of Bull Run/Manassas in July 1861, each side had to contend with something that they also had not figured in to the pre-war calculation, prisoners of war.

In the early stages of the Civil War prisoner exchanges were fairly common. A cartel was established by both sides to oversee the POW issue. This was difficult terrain for the Union in particular which did not want to recognize the legitimacy of the Confederate states. Soldiers were exchanged often to a pledge of parole agreeing that they would not take up arms again against their foe. Paroles were often ignored.

As the war continued and casualties skyrocketed it became evident to Union war planners that former southern prisoners were returning to the fight. Additionally, with the Union’s inclusion of African American soldiers as part of their army, southerners waged a war of retribution against black troops and committed atrocities, most notably the execution of black prisoners captured at Fort Pillow, Tennessee and those taken after the battle of the Crater during the Petersburg Campaign. In response to this, the Lincoln administration refused to continue to exchange prisoners. There was also a cynical side of this policy-if the Confederacy was forced to deal with large numbers of Union prisoners, it would further strain their limited resources. No doubt that thousands of Union men suffered in these camps as a result of this policy. According to Ed Bearss, Chief Historian Emeritus of the National Park Service, “There are no winners in the history of Civil War prisons.”1

Locating the Site

Map 1: The locations of Civil War prisons.

Questions for Map 1

1. List the states where prisons were located. Which states were Union and which were Confederate?

2. Find the Florence Stockade on the map and describe its location relative to the other prisons. Describe where it lies within the Confederate States.

Determining the Facts

Reading 1: The Florence Stockade

When the Civil War began, both the North and the South believed it would be short. Early on in the war, both sides quickly realized that it was going to take a while. Shortly after the fighting began, an important issue emerged: what to do with prisoners taken on the battlefield. Although the North and South often exchanged prisoners at first, more and more soldiers came to the camps as the war dragged on.

The Confederacy considered the prison built in Andersonville, Georgia, in 1864, to be a safe place to keep captured Union soldiers. It seemed far enough from the front lines that the prisoners would be less likely to consider escaping. After General Sherman’s army captured Atlanta in September 1864, this changed. With the Union Army close, the Confederate government feared that Sherman’s troops would attack the prison and free its 33,000 prisoners. To prevent this, the South sent prisoners who were able to travel on trains to temporary prison camps in Savannah, Georgia, and Charleston, South Carolina. When the prison at Charleston quickly became overcrowded, it was clear that another large prison was needed.

The site for the new prison was about one mile southeast of Florence, South Carolina. It consisted of a large field surrounded by pine forests and swamps. Florence was a small town, but three separate train lines connected there, making it easy to ship prisoners and supplies. It also sat relocated prisoners farther from the battlefront. Construction of the prison began in early September 1864 and ended in November. Neighboring plantations provided 1,000 enslaved workers to help build the stockade. The first prisoners arrived on September 15, just after construction began. These first 6,000 prisoners lived in an open field near the prison, guarded by just over 100 soldiers and armed locals. Many of the early arrivals managed to escape, but the surrounding land was harsh and all were recaptured.

The prison at Florence was a stockade, which is a large, open area surrounded by high walls. The word “stockade” also refers to the wall enclosing the area. The stockade wall was rectangular and measured 1,400 feet long and 725 feet wide, enclosing approximately 23 acres. The walls were constructed of whole logs placed vertically in a trench about 4 feet deep. A 5 foot deep dry moat surrounded the outside of the walls to prevent prisoners from tunneling out. The soil from the moat piled against the outside walls, providing a walkway for the guards around the top of the walls. Artillery posts sat at each corner and at the main gate. A shallow ditch 10 to 15 feet inside the walls marked the “dead-line.” Any prisoner crossing that line would be shot without warning.

Sherman’s army continued to march across Georgia until December when it captured the city of Savannah. After taking Savannah, it turned north to invade South Carolina. By February of 1865, Sherman’s forces neared Columbia, only 100 miles west of Florence. The prisoners had to be moved again. This time, there was no isolated location for them, so the Confederate government decided to send them home. The first group left on February 15. The sick went to Wilmington, North Carolina. The healthy traveled to Greensboro, North Carolina where they were transferred back in to Union hands. By March 1865, the Florence Stockade was empty.

Questions for Reading 1

1) Define the terms stockade and dead-line.

2) List two reasons that the stockade was built near the town of Florence.

3) Who actually built the stockade? Why do you think they were used to build it? If you were in charge of construction, would you have used slaves or prisoners? From the Confederate point of view, what would be the advantages and disadvantages of each?

4) If you were in charge of moving large numbers of prisoners, would you continue to build larger prisons or split them up into smaller ones? Which do you think would be easier to build, staff, and supply? Which would be more secure?

Reading 1 was compiled from Official Records of the War of the Rebellion (U. S. War Department 1891, 1895, 1899, 1902); G. Wayne King, Death Camp at Florence (Civil War Times Illustrated 1974); Tracy Power, The Confederate Prison Stockade at Florence, South Carolina (Columbia, SC, manuscript on file at the South Carolina Department of Archives and History, 1991); Robert H. Kellogg, Life and Death in Rebel Prisons (Hartford, CT, L. Stebbins 1868); and Mark A. Snell, editor, Dancing Along the Deadline (Novato, CA, Presidio Press 1996).

Determining the Facts

Reading 2: Life as a Prisoner of War at Florence

The exact number of prisoners held at the Florence Stockade is unknown but the population never exceeded 15,000 at one time.1 Much of what we know about the conditions inside the prison comes from diaries kept by prisoners and memoirs published after the war. Prisoners had little to do, when they could get the supplies, they often wrote letters or kept diaries to pass the time. Supplies were hard to come by, however, so prisoners treasured stubs of pencils and small scraps of paper.

Ezra Ripple of the 52nd Pennsylvania Infantry recorded his experience in the stockade. He lived in a shebang, the most common form of shelters used by prisoners. He described the living conditions in his memoirs:

There was nothing left to do but dig a hole in the ground. As it would have to be roofed over with our gum blankets, we could only dig it as long and as wide as they would permit, and in that hole the four of us had to harbor for the winter. We dug it about three feet deep, but could not make it long enough to allow us straighten out our legs, or wide enough to permit us to lie in any other way than spoon fashion. Our shoulders and hip bones made holes in the ground into which they accurately fitted, and so closely were we packed together that when one turned we all had to turn. Lying all night in our cramped position with no covering, keeping life in each other by our joint contribution of animal heat only, we would come out of the hole in the morning unable to straighten up until the sun would come out to thaw us and limber our poor sore, stiff joints.2

Lack of good food and water was a serious concern in the prison. Rations varied by what was available but generally included small amounts of corn meal, flour, rice, and beans. Prisoners sometimes received sweet potatoes, but never green vegetables. Beef, the only available meat, rarely made it to prisoners. Prisoners could earn higher rations by working in and around the stockade at tasks such as gathering wood. Pye Branch, a stream that flowed through the stockade, supplied the only water for the prison. The water was fairly clean at first, but as more guards and prisoners used it to relieve themselves or to bathe, it became polluted with human waste. Pollution led to sickness and death for many of the prisoners.

Exposure to the weather, poor nutrition, and polluted water all contributed to widespread disease among prisoners. Most prisoners who died succumbed from scurvy and dysentery. Both conditions resulted from poor diets. Insufficient Vitamin C caused scurvy. Dirty drinking water led to dysentery. Prisoners received very little medical care. Although a sheltered hospital existed within the stockade, doctors stationed at the prison did not have the proper medical equipment to help everyone who needed it.

Life inside the prison was very boring. There was nothing for prisoners to do unless they had a specific job. Many spent their time cooking what little food was available or trying to improve their shelter. One interesting event occurred in November of 1864, when the Confederate guards allowed the prisoners to vote in a staged election for President of the United States. In 1864, General George B. McClellan, a former and popular Union general, ran for president against Abraham Lincoln. Those who wanted to vote were given one black pea and one white pea. Those who voted dropped a white pea in the bag for McLellan or a black pea for Lincoln. Prisoners even made speeches for each candidate. In the end, Lincoln won, both in the prison and in the North.

There was little hope of escape from the Florence Stockade. Most attempts failed. Ezra Ripple was a member of a small orchestra of prisoners allowed to go outside the stockade to play for the guards. He and the rest of the orchestra tried to escape, but the blood hounds kept by the guards quickly tracked them down. The only other way out was to swear allegiance to the Confederacy and join a unit of others who had done so. Neither guards nor prisoners trusted these men, called “galvanized Yankees.”

The horrible conditions at the stockade led to nearly 2,800 Union deaths.3 In the six months that Florence Stockade was open, almost one-fifth of the prisoners died. Those that survived were released in February of 1865. Ezra Ripple wrote that when he was released,

...our hearts were so full of joy that we could not act like sane persons, but would cry and laugh and hug each other, and do the most foolish things in our unutterable joy.4

Each day, a group of assigned prisoners gathered the bodies of the prisoners who died in the stockade. The first 400 or so were buried on a small rise just north of the stockade. Bodies soon filled this space so additional burials took place in a larger plot farther to the north on a neighboring plantation. Prisoners dug long trenches to hold the bodies and placed a board marked with a number at the head of each man. A book called a death register recorded each man’s number along with his name and home state if known. The death register disappeared after the war and no complete record of those buried in the trenches exists. These burial trenches served as the starting point for the Florence National Cemetery.

Questions for Reading 2

1) What were the major problems faced by the Union prisoners? How did each problem affect other problems?

2) Explain the terms shebang, scurvy, dysentery, galvanized Yankee and death register in your own words.

3) Imagine that you are a Union soldier who was captured by the Confederates and sent to the Florence Stockade. What would you do first when you reached the inside of the prison and why? What would you do first when you were released and why?

4) How would go about gaining your freedom if you were a Union prisoner? Would you take your chances and try and escape or would you pledge allegiance to the Confederacy? What are the advantages and disadvantages to both methods?

Reading 2 was compiled from numerous primary and published sources including Mark A. Snell, editor, Dancing Along the Deadline: The Andersonville Memoir of a Prisoner of the Confederacy (Presidio Press, Novato, CA 1996); James F. Rusling, Report to Brevet Major General M.C. Meigs, Quartermaster General, Office of the Inspector, Quartermaster Department, Charleston, SC, May 27, 1866, (National Archives, Washington, D.C.); Official Records of the War of the Rebellion (U.S. War Department 1902); and Florence Military Records (South Carolina Department of Archives and History, Columbia, 1864-1865).

1 Official Records of the War of the Rebellion (U.S. War Department 1902) and Florence Military Records (South Carolina Department of Archives and History, Columbia, 1864-1865).

2 Mark A. Snell, editor, Dancing Along the Deadline: The Andersonville Memoir of a Prisoner of the Confederacy (Presidio Press, Novato, CA 1996), page 66.

3James F. Rusling, Report to Brevet Major General M.C. Meigs, Quartermaster General, Office of the Inspector, Quartermaster Department Charleston, S.C., May 27, 1866, (National Archives, Washington, D.C.).

4 Mark A. Snell, editor, Dancing Along the Deadline: The Andersonville Memoir of a Prisoner of the Confederacy (Novato, CA, Presidio Press 1996, pages 138-139).

Determining the Facts

Reading 3: The Confederate Guards

By the time the Florence Stockade opened in September 1864, the Confederate Army desperately needed men able to fight. A conscription program provided part of the solution. A February 1864 law called on a wide age span of men to serve. Men of military age, usually between 18 and 45 yrs old went to combat areas. Older men (45 to 50 years old) and younger boys (17 or 18 years old) joined reserve units in each state. The majority of the guards at the Florence Stockade consisted of South Carolina State Reserve battalions made up of men from several counties near Florence. The 3rd, 4th, 5th, 6th, and 7th State Reserves were assigned to the Florence Stockade.

Like prison life, guard duty was boring and tiring. Guards had to stand at their post with no shelter regardless of the weather. Guards were stationed in three places: 1) around the earthen wall outside the stockade, 2) at posts along the base of the wall, and 3) at posts scattered in various places further from the stockade. Every man served his time on duty. Duty often consisted of standing guard one day, then during the night of the next day. Each soldier also had to do chores in camp. Guards repaired shelters, cleaned the camp, cooked rations, and cut firewood. Out of no more than about 1,600 guards available, as many as many as 300 men were required for duty every day.

Second Lieutenant Thomas J. Eccles, of the 3rd South Carolina State Reserves, wrote a newspaper column describing the activities and conditions of the camp. His writings show that the Confederate guards, especially the reservists, were not well equipped. When they first arrived at Florence in October 1864, Eccles indicated that his men had no shelter and were using blankets as tents. He wrote, “Our men have exercised great ingenuity in construction of tents and huts, which has infringed greatly on their supply of bed clothes, which will inconvenience them greatly when winter sets in.” 1

As the guards settled in to their new camp, their shelter improved. On November 11, Eccles wrote, “...the men have constructed for themselves as comfortable camps as circumstances allow, being without plank or nails. Some, who were able, have brought cloth and made themselves tents, in which they can keep dry.” 2

By late January 1865, the guards were comfortable enough that they did not want to leave Florence. Eccles indicated, “...those who have been anxiously looking for a removal, now express a willingness to remain until the winter is over, as they are generally well provided with comfortable cabins, or tents, with chimnies attached.” 3

Shelter took many forms for the guards. A few large, conical tents, called “Sibley tents,” each housed several men at once. Most of the men built small cabins or huts from split logs. A common method of construction was to dig a hole three to four feet deep and as long and wide as desired, then build short walls out of logs on top of the hole. Poles across the walls formed a frame for a roof, which was usually covered by “shelter halves” (sheets of canvas or some other cloth strung across the poles) or split boards. Shelters generally contained a small fireplace or stove at one end. Chimneys of either sticks and clay or clay-lined barrels or crates rose over these. If sawn lumber was available, the dirt walls and floor inside the hut could be lined to keep out moisture.

Although they were well sheltered and adequately fed a diet of beef, corn meal, flour, rice, beans and molasses, the guards otherwise were not well equipped. Several daily reports mention a lack of coats or even shoes suggesting that guards apparently were issued no uniforms or clothing. We do not know what military equipment, if any, was issued. It appears that they received at least a musket, although probably an older model; a bayonet; ammunition; and a canteen. They had cooking vessels and utensils as well. Local sources probably provided what the Army could not. For instance, Eccles reported that no shovels were available to help dig a well. We know that hand-made shovels were used to complete wells in the camp. A local blacksmith may have made supplies such as shovels.

With shelter, adequate food, and clean water from wells, the Confederate guards remained relatively healthy. Eccles reports small outbreaks of measles, mumps, and typhoid, which were treated at the hospital in the town of Florence. He mentions the deaths of seven members of his battalion, three of these to typhoid.4 Despite exposure to the weather while on duty, it is apparent that the overall health of the guards was good.

Questions for Reading 3

1) How did the Confederacy address the need for fighting men in 1864? Why do you think that younger and older men served as prison guards?

2) What is a Sibley tent? What is a shelter half? If you were a guard who had to build a shelter, what kind would you build and why? Remember that you have to do the work by hand and might not have the tools you need for certain tasks.

3) What did the guards eat? Eccles complained that his rations were ‘short’ because he did not get any tobacco. Would you say that the guards were starving? Why or why not?

4) Compare and contrast the conditions for the prisoners described in Reading 2 with that of the guards. What do the similarities and differences tell you about how the war was affecting life in the South?

Reading 3 was compiled from Thomas J. Eccles, From the State Reserves (a series of articles appearing in the Yorkville Enquirer, York, SC 1864-1865); Sidney Andrews, The South Since the War (Louisiana State University Press, Baton Rouge, LA, 2004); and Florence Military Records (South Carolina Department of Archives and History, Columbia, 1864-1865).

1 “From the State Reserves.” Camp Prison, Florence, S.C., Oct. 7, 1864, E. http://www.oocities.org/sc_seedcorn/Bn03SC_Eccles.html

3 "From the Reserve Forces," Camp Prison, Florence, S.C., Nov. 11, 1864. E.

3 "From the Reserve Forces," Florence, S.C., January 27, 1865, E.

4 Thomas J. Eccles, From the State Reserves (Yorkville Enquirer, York, SC, 1864-1865).

Determining the Facts

Reading 4: Archeology in the Guard Camp

After the Civil War, the site of the Confederate guard camp became an agricultural field and was used to grow pine trees. It remained in this use through the 20th century. Plowing of the field over the years created a thick “plow zone,” the upper layer of soil disturbed by the plow. This layer was about 30 centimeters thick and lay on top of a light-colored, undisturbed soil. In general, plow zones very often contain “artifacts,” which are objects made, used, or modified by people. Plowing moves artifacts around, so archeologists do not know where they were originally located. An artifact’s position in the soil relative to other artifacts is called its “context.” An artifact’s context is very important in using it to learn about the past.

Archeologists do not know the context of the artifacts discovered in a plow zone because plowing changes the original relationships of these artifacts to each other. Therefore, archeologists do not need to be as careful when clearing this layer. In this case, they removed the plow zone using a backhoe and a large earth-moving machine called a pan. As the plow zone was removed, an archeologist watched the soil for changes in color, which might indicate some form of human activity. These color changes are called “features” and often appear as areas of darker soil. When archeologists located a feature at the Florence Stockade, they first marked it with a small flag and scraped the remaining plow zone away to reveal its edges. Then they drew it on a map and photographed it. After that, workers excavated the soil within the feature by hand until the dark soil was gone.

The removal of the plow zone revealed 521 features. Of these, 179 were excavated. The archeologists used hand tools to dig out dark soil within the feature. Commonly using small trowels to excavate features, archeologists sometimes need to use even smaller tools. Dental picks and brushes help excavate delicate artifacts, as they did at this site. The soil from each feature was screened to see if it contained artifacts. Screening soil means sifting through wire mesh, usually with 1/4 inch holes. When the soil falls through the screen, it leaves larger objects behind, such as artifacts. Small soil samples go to a laboratory to see if they contain small seeds or other plant materials. These methods recovered almost 6,000 artifacts, most of which dated to the Civil War.

Archeologists could tell what some of the many excavated features from the Florence Stockade were used for by their size and shape, but they have yet to determine the function of others. Feature types included structures, latrines or privies, pits, post holes, trenches, and wells. Confederate guards dug most of the features, but tree roots also caused a few.

Artifacts uncovered at the Florence Stockade included a wide variety of materials and objects owned or used by the Confederate guards. The term for items related to the construction of shelters or other structures is “architectural artifacts.” Artifacts from this category included nails, pieces of brick, and window glass fragments. Artifacts used to store, cook, and consume food and beverages were very common. They included whole glass bottles, hundreds of bottle fragments, pieces of ceramic plates and jugs, metal cans, and utensils. These are called “kitchen artifacts.” “Military artifacts” included bullets, percussion caps, bayonet fragments, a tin cartridge box, a nearly complete tin canteen, and fragments of other canteens. “Personal artifacts” are things that belonged to one soldier, such as teeth from hard rubber combs, hard rubber finger rings, buttons, and part of a picture frame. Other artifacts included various types of metal hardware, such as two shovel blades.

The shovel blades indicate the difficulties that guards faced. As discussed in Reading 3, Thomas Eccles wrote that his men had a hard time digging a well because they had no shovels. A shovel was a common, factory-made item by the mid-19th century and should have been easy to acquire. But by 1864, the Confederacy had much less ability to manufacture or import basic goods like shovels. This was a major problem and greatly contributed to the North’s eventual victory. The shovels recovered from the camp site were hand-forged by a blacksmith, likely a local person hired to make them.

Animal bone was another important type of artifact. Archeologists recovered thousands of fragments of animal bone, weighing about 88 pounds in total. Most of the bone came from cows, but some came from pigs, chickens, and other birds. The presence of this much bone proves that the Confederate guards had meat to eat. In contrast, we know that the prisoners had almost none. A long-believed theory among historians says that the Union prisoners starved because the guards were starving as well. In his newspaper column, Eccles twice addresses the amount of food the prisoners received. On October 7, 1864, he wrote that, "...they cook their own rations, which of course they complain of, however plentiful they may be.” 1 On November 4, he wrote, “They are well fed, drawing the same rations we do.” 2

Questions for Reading 4

1) Define or describe the terms plow zone, context, feature, architectural artifact and personal artifact.

2) The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs sponsored this archeological excavation. The Department's National Cemetery Administration was planning to expand the Florence National Cemetery. Without this excavation, how do you think the planned construction would have affected the archeological features and why?

3) How is the shovel blade recovered from the camp indicative of factors that led to the Confederacy's coming defeat?

4) How do you think the information gained from the archeological investigations might either verify or disprove information gained from the documentary evidence? Give one specific example of how the archeological evidence from this site verifies the historical record and one of how it disagrees with the historical record.

Reading 4 was adapted from Paul G. Avery and Patrick H. Garrow, Phase III Archaeological Investigations at 38FL2, The Florence Stockade, Florence, South Carolina (Knoxville, TN, MACTEC Engineering, 2008).

1 “From the State Reserves,” Camp Prison, Florence, S.C., Oct. 7, 1864, E. http://www.oocities.org/sc_seedcorn/Bn03SC_Eccles.html.

2 “From the Reserve Forces,” Camp Prison, Florence, S.C., Nov. 4, 1864, E. http://www.oocities.org/sc_seedcorn/Bn03SC_Eccles.html.

Visual Evidence

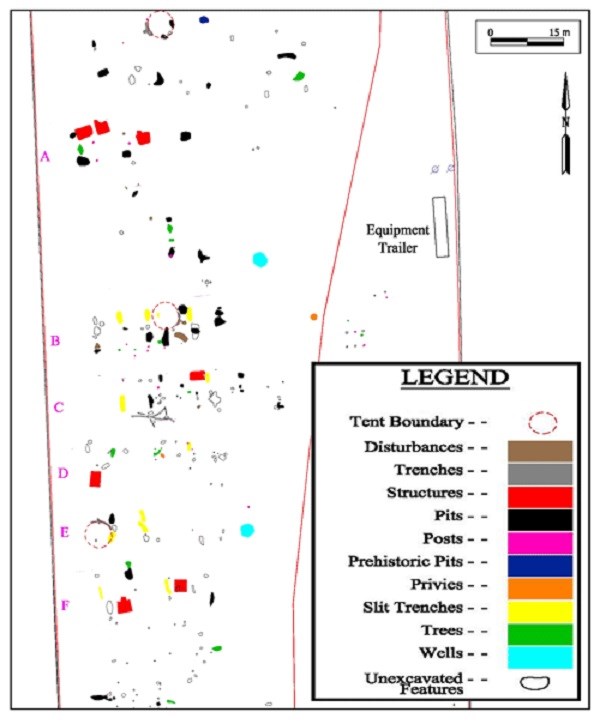

Drawing 1: Site Plan of Archeological Excavation.

(Map by Paul G. Avery)

This map shows a portion of the area that was excavated by archeologists. This area is where some of the Confederate guards lived. Each shape represents an archeological feature. A feature is an area of disturbed soil caused by human activity, such as digging a pit or building a hut. Each color represents a different type of feature. Red features are structures, yellow features are slit trenches, black features are pits and the blue ones are wells.

Slit trenches, also known as latrines, were open trenches used by the soldiers as toilets. The purple letters mark the locations of possible company streets.

Questions for Drawing 1:

1) Military regulations dictated that camps should be organized and orderly. Does this camp appear to follow regulations? Why or why not?

2) Look at the structures. Based on their shapes, how many different types of structures do you think were here?

3) Look at the tent boundary feature in the area labeled ‘B’. This line marks where a large, circular tent once stood. Notice that there are several features located in the same area as the tent. Why do you think there are so many features right around the tent?

Visual Evidence

Map 2: Aerial view of the Florence Stockade, the Florence National Cemetery and the campground of the Confederate guards.

![(USGS National Agriculture Imagery Program [NAIP]) (USGS National Agriculture Imagery Program [NAIP])](/articles/images/Map-2-Aerial-View-of-Stockades.jpg?maxwidth=1300&autorotate=false)

This map shows the location of the Florence Stockade, the Florence National Cemetery and the area where archeologists located the campground of the Confederate guards.

Questions for Map 2:

1) Use the scale bar and measure the distance in meters from the Stockade to the original location of the Florence National Cemetery. What problems do you think the prisoners who had to bury the dead had in transporting the bodies that distance? Why do you think the Confederates chose that spot to bury them?

2) Examine the area west of the Confederate Camp. Based on what you can see on the ground, do you think that archeologists could find more of the camp in that area? Why or why not? (Refer back to Reading 4, if necessary)

Visual Evidence

Photograph 1: Artifact A.

(Patrick H. Garrow, photographer)

Questions for Photograph 1:

1) Look back at Reading 4 for descriptions of artifacts found at this site. What is this artifact? Does it appear to be broken or complete?

2) Refer back to Drawing 1, what types of archeological features might this artifact have helped create?

Visual Evidence

Photograph 2: Artifacts at the bottom of a well.

(Paul G. Avery, photographer)

These artifacts were recovered from the base of a well, about 20 feet below the ground surface. This photograph shows the position in which the artifacts were discovered. The scale bar is 50 centimeters in length.

Questions for Photograph 2:

1) How many artifacts do you see? Do they have “context”? (Refer back to Reading 4)

2) How do you think these artifacts ended up at the bottom of a well? The artifact at the bottom center of the photograph is a ceramic container with the mouth and neck of a glass bottle sticking out of the soil inside the container. How do you think the bottle came to be inside the other container?

3) The black and white object at the bottom of the photograph is a tool used by archeologists. What do you think it is used for? Why do you think it would be important?

Visual Evidence

Drawing 2: The Florence Stockade.

This map of the Florence Stockade was drawn by Robert H. Kellogg, who was held as a prisoner of war at the Florence Stockade.

Questions for Drawing 2:

1) Locate the stockade walls, the deadlines, the hospital, and the brook. Why do you think the stockade was built with the stream flowing through it? Why might they have wanted streets?

2) The prisoners lived on the east side of the stream. Every day, the guards made them march across the bridge (number 7 on the map) so that they could be counted. Why do you think it was important for the guards to count the prisoners every day?

Visual Evidence

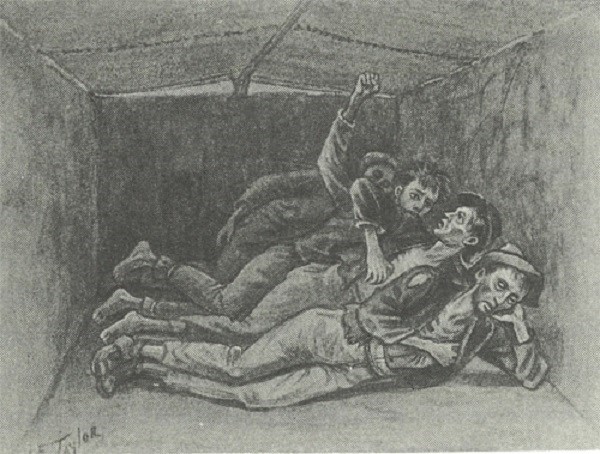

Drawing 3: In a hole.

(Courtesy of the Lackawanna Historical Society)

This drawing is part of a series commissioned by Ezra Ripple for his book about his time as a prisoner of war at Florence from 1864 to 1865. Reproduced from Dancing Along the Deadline (1996), edited by Mark A. Snell.

Questions for Drawing 3:

1) How many people are there in this picture? Where are these men and what do you think they are trying to do? (Refer to Reading 2, if necessary.)

2) What are the walls and roof of this structure made of and how was it constructed? (Refer to Reading 2, if necessary.) If you had been a prisoner in the Florence Stockade, do you think you would have wanted to help build and share a structure like this or would you have created another kind of shelter? Explain your answer, keeping in mind the work required to build a structure and the tools available.

3) What do you think the two men in the foreground are doing? Why would they be doing that? (Refer to Reading 2, if necessary.) Why do you think Ripple included this in his book about his time at Florence?

Putting It All Together

By looking at “Comfortable Camps?” Archeology of the Confederate Guard Camp at the Florence Stockade, students can more easily understand the workings of a Civil War prison camp, including not only prisoners’ living conditions, but also that of the guards. The following activities will provide students with an opportunity to better comprehend the Civil War prison experience and the toll it took in lives, and also understand ways in which archeological investigations help us learn more about the past.

Activity 1: Design a Campground

Divide students into smaller working groups in whatever way will maximize their ability to view images on the internet. Have students peruse the following maps of civil war camps. All are freely available at the Library of Congress website.

- Camp Chase (Union)

- Camp Lawton (Confederate)

- Elmira Prison (Union)

- Johnson’s Island (Union)

- Point Lookout (Union)

- Rock Island Prison (Union)

- Salisbury Prison (Confederate)

If you wish to include Andersonville Prison (Confederate), which is featured in its own Teaching with Historic Places lesson plan, there are many usable maps available at this link.

After students have viewed all of the maps, ask them to identify on each map where prisoners were kept. How did the geography of the camps help the guards control the prisoners? Students should consider both natural features (rivers, open fields) and built features (fences, guard posts). Have students list similarities and differences between the different maps. Do students notice any differences between U.S. and Confederate prison camps?

Activity 2: Archeology of Your Room

Archeologists rely on the things that they excavate from the ground to tell them about the culture, history, and technology of the people who lived in the past. This information, along with historical records, allows them to form a reasonably accurate picture of what life was like in the past. To demonstrate this lesson, instruct each student to examine the contents of their room at home and think about what items would survive if buried in the ground for a long time and which would not. If archeologists excavated the spot where their room once stood in 200 years, what would they find? What could the archeologists determine about the culture and technology of the early 21st century from these items? Have each student write an essay describing what they think would be found and why, as well as how they think it would be interpreted. They should include details, like what their clothing would leave behind or the things on their desk or shelves. Have several students either read their papers or at least summarize the conclusions that archeologists would make about life in the United States in the early 21st century. How are the students’ “artifacts” and conclusions alike? How are they different? The class would then discuss how the things found at the site of their room would differ from the things recovered at the Florence Stockade and how they are the same.

Activity 3: Learning about war veterans buried in your Community

Find out if there is a national cemetery nearby. The National Cemetery Administration’s website (www.cem.va.gov) has a list of them with maps and driving directions. If you do not have a national cemetery nearby then visit a local cemetery or ask a representative from the cemetery to come speak to the class. Have the students talk to the staff and look at the markers. If it is a local cemetery inquire about Civil War veterans who may be buried there. In the case of the national cemetery, the students will conduct additional research on the chosen National Cemetery to learn about the history of the facility. The students should present their findings in an essay, PowerPoint or website. Their research should focus on answering the following questions:

-

When was the cemetery opened and what is the earliest burial there?

-

Why was the cemetery located there?

-

What lead to the founding of the cemetery?

-

Are people still being buried in the cemetery? If not, when was the latest burial?

-

Who is allowed to be buried there and has that changed over time?

-

In what wars did the veterans buried there serve?

In the case of the local cemetery students should focus on the Civil War veterans buried there and focus on answering the following questions:

-

Who was this person?

-

Where did he serve?

-

Why are they buried in this cemetery?

-

What does their headstone indicate about this person?

If you have a national cemetery in your vicinity find out if there are certain days of year (Veterans Day/ Memorial Day) when the graves are decorated with flags and have your students participate in the commemorative program. If the local cemetery is in need of upkeep organize a clean-up day or conduct needed research on the Civil War veterans buried there.

Activity 4: Women in the Civil War

One of the more unusual stories related to the Florence Stockade is that of Florena Budwin. Her husband was a Union soldier and she could not bear to see him leave for the war. She disguised herself as a man and followed him through the war until they were captured and sent to Florence. Her husband died while at Florence. Her true gender was discovered by a doctor while she was in prison and legend says that she actually gave birth there. She continued to remain in the prison and acted as a nurse until she died of sickness. She is buried in the national cemetery with her own marker.

Have the students research the roles of women during the Civil War and compare them with women in the military today. This can be accomplished by interviewing women in the local community who served in the military. Your local VFW or American Legion Post can help students identify veterans in the community. Have the students write essays or develop interpretative exhibits about the person that can be exhibited in school. This would make for a good Women’s History month activity in your school or as a National History Day project if the theme was applicable.

"Comfortable Camps?" Archeology of the Confederate Guard Camp at the Florence Stockade--

Supplementary Resources

By looking at the Florence Stockade, students can more easily understand the workings of a Civil War prison camp, including the living conditions of prisoners and how they coped with the prison environment. Those interested in learning more will find that the websites below offer a variety of materials on Civil War prison camps and on the Civil War generally.

National Park Service, Andersonville National Historic Site

Andersonville is probably the most well known of the Civil War prison camps. Andersonville National Historic Site is a unit of the National Park System. The park's web page details the history of the park and visitation information.

National Park Service, Civil War Website

Visit the official National Park Service Civil War Web Site. This site offers the current generation of Americans an opportunity to know, discuss, and commemorate this country's greatest national crisis, while at the same time exploring its enduring relevance in the present. The website includes a variety of helpful features and links such as the “Facts” page, which provides a detailed breakdown of the human, financial, and technological resources available to the Union and Confederacy.

National Park Service, Civil War Soldiers & Sailors System

The National Park Service's Civil War Soldiers & Sailors System is a recently created database containing facts about Civil War servicemen, lists of Civil War regiments, and descriptions of significant Civil War battles. Also on this site is a descriptive history of African-Americans in the Civil War.

National Park Service, Southeast Archeological Center

The National Park Service's Southeast Archeological Center offers a detailed discussion of their archeological investigation at Andersonville Civil War Prison. The site includes historical background and a description of the conditions at Andersonville. Teachers and students could compare the findings here with the findings outlined in this lesson.

National Archives and Records Administration (NARA)

The National Archives and Records Administration offers a wealth of information about the Civil War. Included on the site is a photographic history of the Civil War. The photographs are organized into the following categories: Activities, Places, Portraits, and Lincoln's Assassination.

NARA also provides information about researching Civil War records. Included on the site is links to information about the Union and Confederate Armies.

The Valley of the Shadow Project

The Valley of the Shadow Project is a joint production by the University of Virginia Library and the Virginia Center for Digital History. The site offers a unique perspective of two communities, one Northern (Franklin County, Pennsylvania) and one Southern (Augusta County, VA), and their experiences during the American Civil War. Students can explore primary sources such as newspapers, letters, diaries, photographs, maps, military records, and much more.

Further Reading

Students interested in learning more may want to read Lonnie Speers Portals to Hell: Military Prisons of the Civil War (Harrisburg: Stackpole Books, 1997), a definitive and balanced account of the history of Civil War prisons, Civil War Prisons by William B. Hesseltine (Kent: Kent State University Press, 1997) a short and crisp synopsis of Civil War prisons or Haunted by Atrocity: Civil War Prisons in American Memory by Benjamin G. Cloyed (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2010) which examines the conflicts and problems of how Americans have chosen to remember Civil War prisons.

Tags

- civil war

- civil war prison

- civil war prisoner of war camps

- south carolina

- south carolina history

- twhp

- teaching with historic places

- archaeological artifacts

- archaeological site

- archaeology

- archeology

- military wartime history

- mid 19th century

- military history

- battle

- civil war battles

- civil war union army

- prison

- prisoner of war

- prisoner-of-war camps

- archaeological dig

- archaeology site

- twhplp