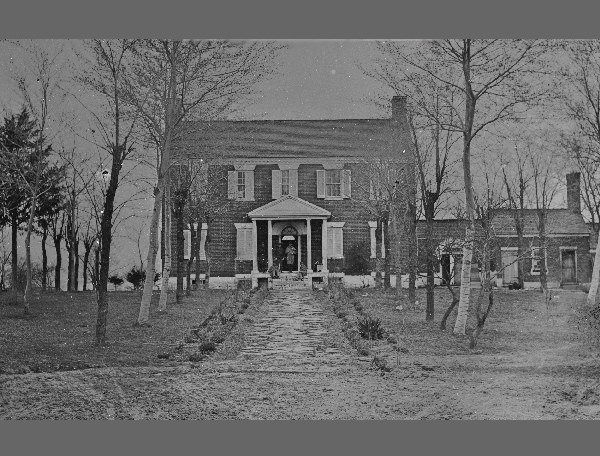

Gen. Beauregard's Headquarters This month the first major battle of the war took place in northern Virginia. Pressured by Lincoln and the northern Congress to do something, Union General Irvin McDowell lead his ill-trained army out of Washington toward Manassas. There he hoped to rout the Confederates and push on to Richmond. His movement was no secret, as spies were active and the movement of 35,000 men could not be hidden from observers. Waiting at Manassas were Confederate troops under General P.G.T. Beauregard. Learning of the movement, another Confederate force moved toward Manassas to help Beauregard. In one of the first major uses of railroads in warfare, Confederate General Joseph E. Johnston (of Farmville) moved his army from the Shenandoah Valley to assist the southern forces at Manassas. This was the one big battle that both sides felt could end the war. At Manassas on July 21st, both sides clashed in the heat. Union troops initially pushed the Confederates back. Johnston's reinforcements, however, arrived just in time. After a final two-hour fight for Henry Hill, the exhausted Federal troops broke and retreated. Yet the Confederates were just as disorganized in their victory as the Union forces are in their defeat. McDowell lost 2,896 men and the Confederates suffered 1,982 casualties. Many units, like 11th Virginia of Lynchburg, pick up new equipment like canteens, haversacks, blankets, and rifles, after the battle. Southside men from the 2nd Virginia Cavalry (including many Appomattox county men) and the 18th Virginia, saw their first battle at Manassas. Soldiers called the thrilling, terrifying experience of their first combat as, "Seeing the Elephant." The 18th Virginia fought on Henry House Hill, the epicenter of the battle. In their trial by fire 6 men were killed and 13 wounded, relatively light casualties by later standards, but sobering for the men who experienced the fight. Another Southside unit, largely from Pittsylvania County, the 38th Virginia, was delayed in its journey toward Manassas. These men from Danville, Chatham, Halifax, and Mecklenburg missed the Battle of Manassas, joined the army there the next day, no doubt disappointed to have missed it. Lynchburg soldier Charles Blackford with the 2nd Virginia Cavalry noted, "I saw Edmund Fontaine . . . resting on a log on the roadside. I asked him what was the matter, and he said he was wounded and was dying .He said it very cheerfully and did not look as if anything was the matter, but as we came back we found him dead and some of his comrades about to remove his body. It was a great shock to me, as I had known him from his boyhood . . ." In western Virginia, far from the scene of major fighting at Manassas, the Hampden-Sydney Boys surrendered after fighting their first battle at Rich Mountain. The young men, from Hampden-Sydney College and Union Theological Seminary, were left in an exposed position and became surrounded by Union troops. Many were also sick with measles and weak from long marches and poor food. For the time being, the war was over for the Prince Edward County men; they were paroled and returned home in 1862. Some enlisted again in other units, some avoided the war as best they could, but the Hampden Sydney Boys ceased to exist. Civilians also felt the impact of war for the first time, with family farms becoming battlefields, hospitals, headquarters, and military staging areas. One Manassas plantation, the home of Wilmer and Virginia McLean, Yorkshire, was used by Captain Edward Porter Alexander, one of General Beauregard's staff officers. During the battle, Confederate troops used McLean's barn for a hospital, and Union shells hit McLean's outdoor kitchen. The civilians of northern Virginia felt the impact of war as armies marched, camped, and fought across the region. |

Last updated: March 31, 2012