Antietam Battlefield Library “In this charming valley, soon to be stained, yet hallowed, with blood and marking a great battle of American history-of all history- war now stalked and we follow its footsteps to the banks of the Antietam and the Potomac, to note the ground of impending battle and the approaches thereto.”[1] This is how Colonel Ezra Ayers Carman began his over 1,000 page manuscript that accompanied a series of 14 maps which mark the troop movements of the Battle of Antietam. These maps and manuscript became the most detailed record of the events of the battle we have today and are still used to conduct research. These documents are the centerpiece of the work completed by Ezra Carman and the Antietam Battlefield Board. The work completed by the Battlefield Board in the 1890s set the battlefield on the course that made it what it is today.

Prior to the 1890s, the battlefield of Antietam was comprised of privately-owned farmland and the National Cemetery. In the immediate aftermath of the battle, the farmers of Sharpsburg attempted to pick up the pieces, remove debris from their fields, bury the dead, and return to life as usual. It would take several years for the citizens of Sharpsburg to reclaim their homes and farms. In 1865, writer John T. Trowbridge described Sharpsburg as a “tossed and broken sort of place, that looked as if the solid ground swell of the earth had moved on and jostled it since the foundations were laid.”[2] This process of returning to normal was made easier with the establishment of the National Cemetery in 1867. The Union dead were disinterred from the famers’ fields and placed in the National Cemetery. Likewise, the Confederate dead were removed and placed in local cemeteries in the area. However, once the dead were removed from the field and the National Cemetery was established, the battlefield remained dormant. The land served as a place of remembrance and reflection and as a peaceful place in which the people of the quiet community of Sharpsburg raised their crops and children. [1] Ezra A. Carman, The Maryland Campaign of September 182 Vol. II: Antietam, ed. Thomas G. Clemens (El Dorado Hills, California: Savas Beatie LLC, 2012), 1.

[2] John T. Trowbridge, The Desolate South, 1865-1866: A Picture of the Battlefields and of the Devastated Confederacy, ed. Gordon Carroll (New York: Duell, Sloan and Pearce, 1956), 25-27, quoted in Susan Trail, “Remembering Antietam: Commemoration and Preservation of a Civil War Battlefield,” PhD diss., (University of Maryland, 2005), 66.

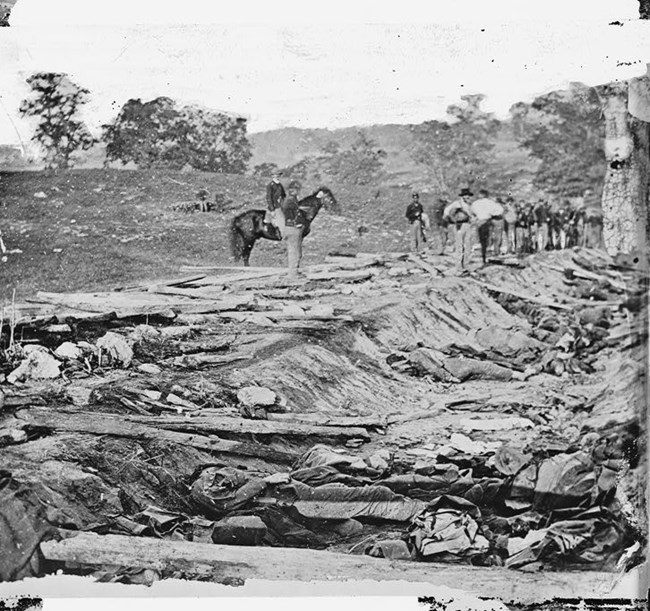

Alexander Gardner/LOC This changed in the 1890s. Prior to this time, the establishment of the National Cemetery was the only progress made in preservation and remembrance. In the more than 25 years after the battle of Antietam, no real effort was made to attempt to preserve the land that made up the battlefield. The nation was focused on reconciliation and reunification: moving forward, not looking back. This would change in the last decade of the nineteenth century. Civil War veterans, now older middle-aged men, began to reflect on their Civil War experiences and their lost comrades. Many veterans, now members of Congress, had the power and influence to acquire funds to preserve the land on which they had fought. This happened first at Chickamauga and Chattanooga, where the first federal battlefield park was established in August of 1890. The law that created the park also authorized the acquisition of over 7,500 acres, with an initial funding of 125,000 dollars and a three-member commission to oversee the process. Around this time, a bill to create a federal battlefield park at Antietam was put forth by Congressman Louis McComas. In June of 1890, he added a small addition to a large appropriations bill that a set aside “15,000 dollars to survey, locate, and preserve the lines of battle at Antietam.”[1] The bill was signed into law on August 30, 1890. This was the formation of Antietam National Battlefield. Unlike the standalone bill that created Chickamauga, Antietam was established with a few sentences added to a massive spending bill. McComas did introduce another bill in September to ask for a three-person commission and 150,000 dollars to mark the major points of fighting, purchase the land that made up the battlefield, and build roads to provide access to the locations of the key phases of the battle. However, McComas lost his bid for reelection and was unable to continue to lobby for Antietam and the bill to establish a full scale military park at Antietam died. Without veterans in Congress like Dan Sickles, who pushed through the establishment of Gettysburg as a battlefield park in 1895, and other veterans who lobbied for Shiloh in 1894 and Vicksburg in 1899, Antietam remained a champion-less afterthought in a larger appropriations bill. [1] Susan Trail, “Remembering Antietam: Commemoration and Preservation of a Civil War Battlefield,” PhD diss., (University of Maryland, 2005).

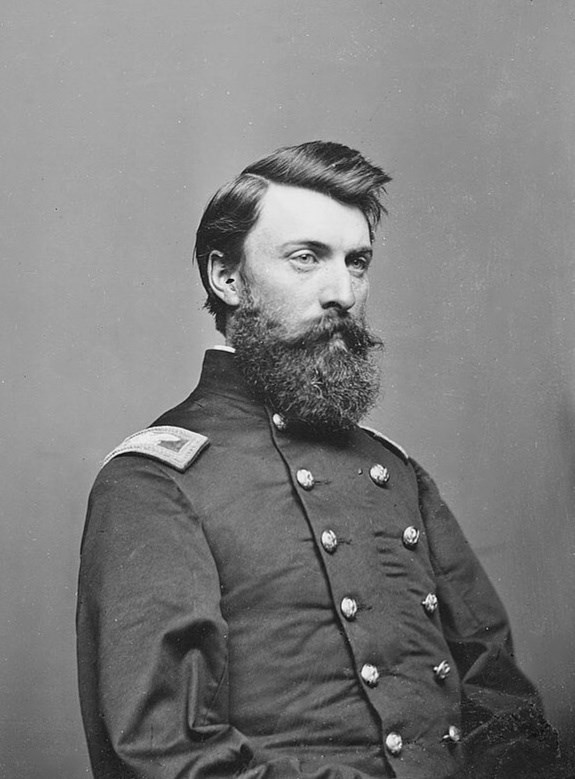

Antietam Battlefield Library From its creation, Antietam would take a course very different from its sister parks. Unlike the five other National Battlefield Parks, Antietam was not created by a full-blown act of Congress and did not receive large amounts of funding for massive tracts of land to be preserved. Likewise, it lacked a commission to oversee land acquisition and monumentation. Legislation for Antietam called, not for a large commission to oversee the park, but a small board with only two members. These members were Union representative John C. Stearns and Confederate representative Henry Heth. Though both were veterans, neither had any personal connection to Antietam, unlike Ezra Ayers Carman, Colonel of the 13th NJ who fought in the West Woods during the battle. Carman was an active member of veteran organizations and a member of the Board of Trustees for the Antietam National Cemetery. He personally lobbied to be appointed to the Battlefield Board. However, due to partisan politics, Carman was overlooked. Antietam also lacked historians and engineers that other park commissions had. Stearns and Heth began their work in August of 1891. They began by locating and marking the positions of battle and tried to negotiate with local farmers to sell their land. They began to place temporary wooden stakes on the fields to mark troop positions. However, their temporary markers were constantly being destroyed as farmers cultivated their fields. Likewise, both men were elderly and had to take frequent breaks due to ill health. Farmers were often uncooperative in negotiations and the map that they used for marking positions of troops was inaccurate at best. Furthermore, they lacked the funding provided to other parks like Chickamauga and Gettysburg to acquire large tracts of land to place these markers. By 1894, the two men had made little headway. In January of that year, Stearns resigned due to illness and the first attempt at preserving the battlefield ended in failure.

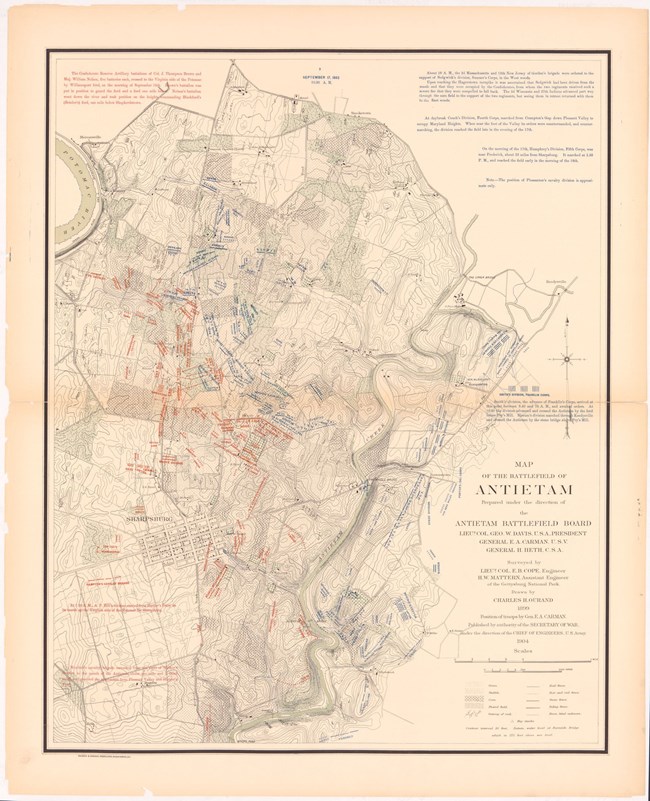

Antietam National Battlefield Library With Stearns gone, the War Department decided to make a change. This time, Col. Ezra Carman who was appointed “historical expert” of a new Battlefield Board that was established in 1894. Carman was joined by Major George B. Davis, who became president of the board and the Union representative, and Henry Heth, who was reinstated as the Confederate representative. With the establishment of a new board, Davis steered Antietam in a new direction. Davis quickly recommended changes that became known as the Antietam Plan. Davis was a Civil War veteran who continued his military career after the war. Unlike Stearns and Heth, he was young, energetic and interested in furthering his military career by pleasing the War Department. To do this, he had to save money. His plan would not involve buying thousands of acres of land like the other battlefield parks, instead the War Department would only have to buy 10 acres of land for the placement of informative markers and an interconnected road system designed to give visitors access to the major points of fighting. This was a departure from previous parks like Gettysburg and Chickamauga that acquired thousands of acres of land to preserve the battlefields in their entirety. Instead, Davis’s plan involved only buying enough land to place 200 cast iron tablets to explain the tactical maneuvers of battle, 100 iron poles with red or blue balls to mark the lines of battle, and two wooden observation towers as orientation for visitors. This plan was vastly cheaper than the cost establishing of other military parks. Because of this, the Antietam Plan was readily accepted by the War Department. With the plan approved, the board set about implementing it. Carman and Davis divided the work of writing the text for the informative tablets. However, they soon found they lacked the necessary information. They began to reach out to veterans and ask for help. The Board even placed advertisements in major newspapers asking for information. Veterans responded in large numbers and Carman exchanged correspondence with hundreds of soldiers. He sent them maps on which to mark the locations where they had fought and some veterans even returned to the battlefield and led Carman to these sites. From these correspondences, by August of 1895, Carman and Davis were able to place 200 tablets on the field. As well, Davis and Carman began to develop a system of roads to connect the major points of battle. To save money, the plan was modified and only one stone observation tower was placed and the iron poles were scrapped. Laying the Groundwork With the completion of the 200 tablets in 1895, Heth and Carman were soon relieved of duty. Likewise, George B. Davis was reassigned to active duty in the Spanish American War and replaced by George W. Davis, another veteran who served with the 11th CT. George W. Davis had Heth and Carman reinstated and called for a new map to replace the old, inaccurate map from 1867 that the Board had been forced to use. The topographic elements of the map were completed by the chief engineer of the Gettysburg battlefield Emmor Cope. Once those elements were finished, it was turned over to Ezra Carman. He was tasked with marking the positions of troop movements on the maps. In this work, Carman would truly earn the title of “historical expert.” He spent the next 20 years of his life creating and reworking a series of 14 highly detailed maps of troop movements from the beginning to the end of the twelve-hour battle. These maps called the Atlas of the Battlefield of Antietam, along with Carman’s manuscript are the centerpiece of the preservation work done by Carman and the Battlefield Board. According to Antietam Battlefield Board President George W. Davis, Carman “probably knew more about Antietam than anyone ever had known or will know. He had the advantage over present historians of having fought there himself and of talking with many others who had also participated in the fight. Such opportunities must have offered him insights into the battle which no one else can ever hope to achieve.”[1] Ezra Carman would even leave unfinished correspondence about Antietam on his desk when he died on December 25, 1909. Other than the addition of more tablets at Harpers Ferry, Shepherdstown, and South Mountain, which brought the total number of tablets to 403, the battlefield remained static. With their work complete, the Battlefield Board disbanded in 1898. The War Department maintained stewardship of the battlefield until August 10, 1933 when it was transferred to the National Park Service. Ezra Carman and the Battlefield Board made the first and most important strides in creating the battlefield as we know it. They documented the history of the battle itself and laid the groundwork to preserving the fields as a truly hallowed reminder of a great battle of American history and of all history. Works Cited Carman, Ezra A. The Maryland Campaign of September 182 Vol. II: Antietam. Edited by Thomas G. Clemens. El Dorado Hills, California: Savas Beatie LLC, 2012. Trail, Susan. “Remembering Antietam: Commemoration and Preservation of a Civil War Battlefield.” PhD dissertation. University of Maryland, 2005. [1] Maj. George W. Davis to Hon. George D. Meiklejohn, March 28, 1898, file 700, ABC, Entry 707, RG 92, NA; Lilley, “Antietam Battlefield Board,” 346-348, quoted in Susan Trail, “Remembering Antietam: Commemoration and Preservation of a Civil War Battlefield,” PhD diss., (University of Maryland, 2005), 230.

|

Last updated: April 13, 2020