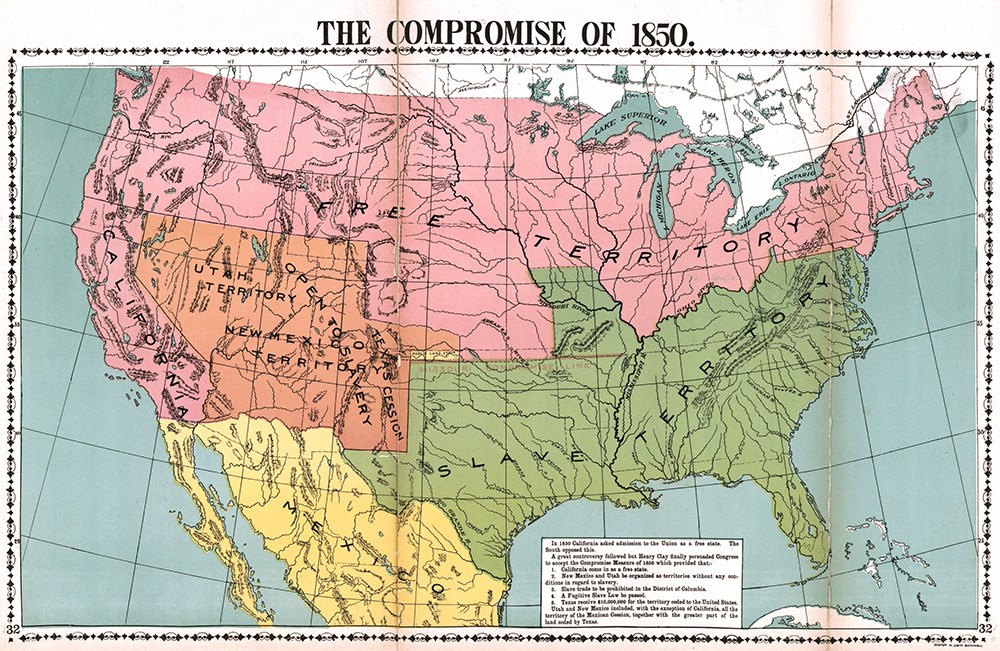

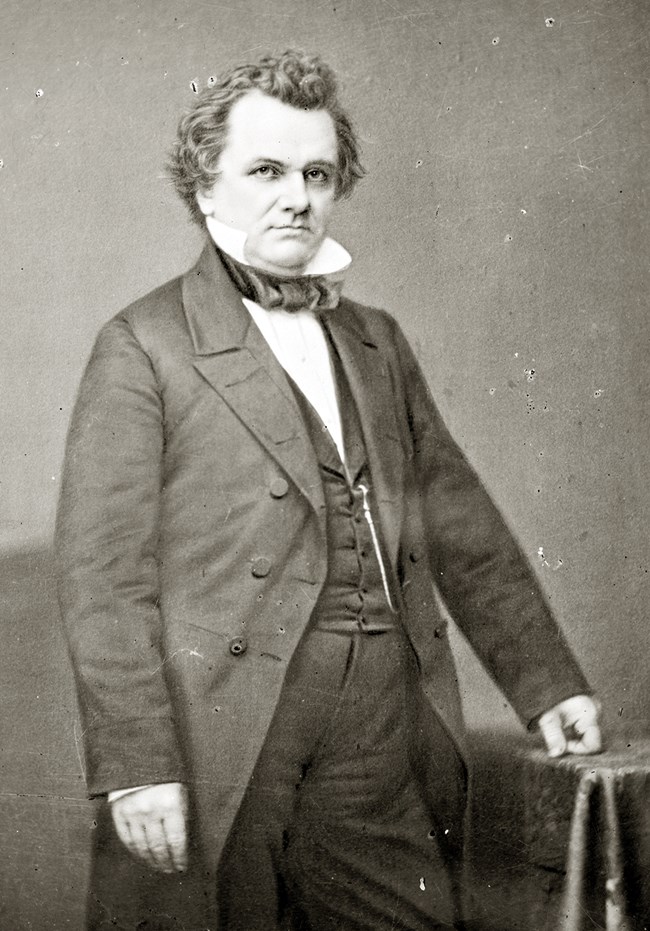

Compromise of 1850The acquisition of new territory from the Mexican-American War continued to incite tensions along sectional lines. The more territory the United States acquired, the more intense and complicated the debate over the expansion of slavery became. The 1849 gold rush, meant that new settlers flocked to California, and it quickly reached the population requirement to apply for statehood. Settlers in California wanted it to be admitted as a free state. However, if California was admitted as a free state it would upset the balance of power in Congress. Congressmen turned to the Great Compromiser, Henry Clay, to propose a solution. He offered an omnibus bill to, “adjust amicably all existing questions of controversy . . . arising out of the institution of slavery.” Along with the question of slavery in California, his proposal addressed other slavery-related disputes including the Texas border and the continuation of slavery and the slave trade in Washington, D.C. His series of bills included the following provisions: the admission of California as a free state, a clear definition of Texas’s border, the establishment of territorial governments in Utah and New Mexico, the abolition of the slave trade in Washington, D.C., and changes to the Fugitive Slave Act. It took nearly seven months of debate and the assistance of Stephen A. Douglas for the Compromise of 1850 to get the support it needed to become law.

Library of Congress

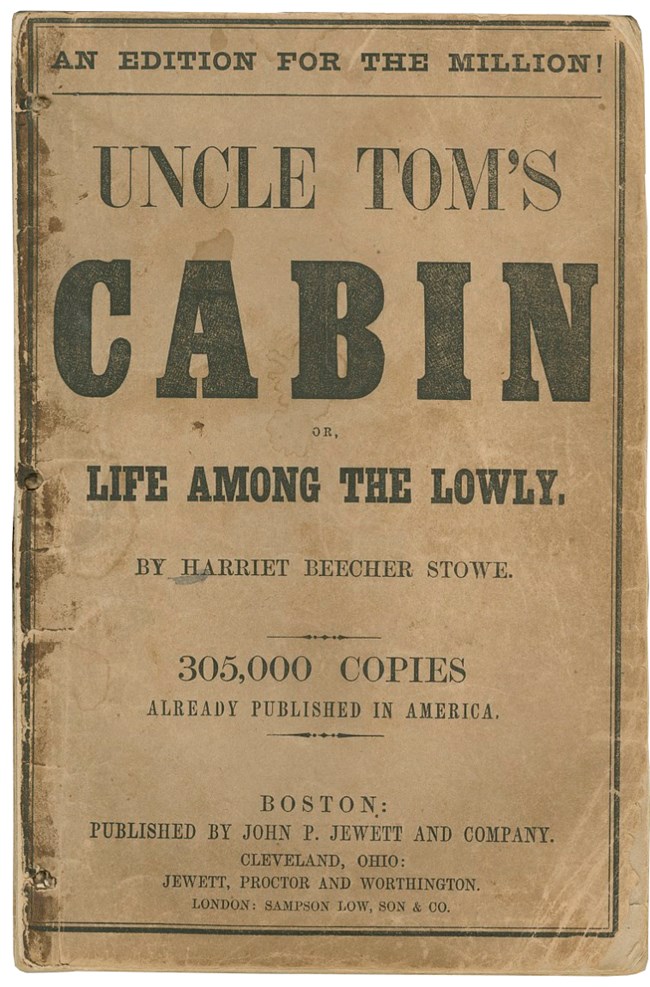

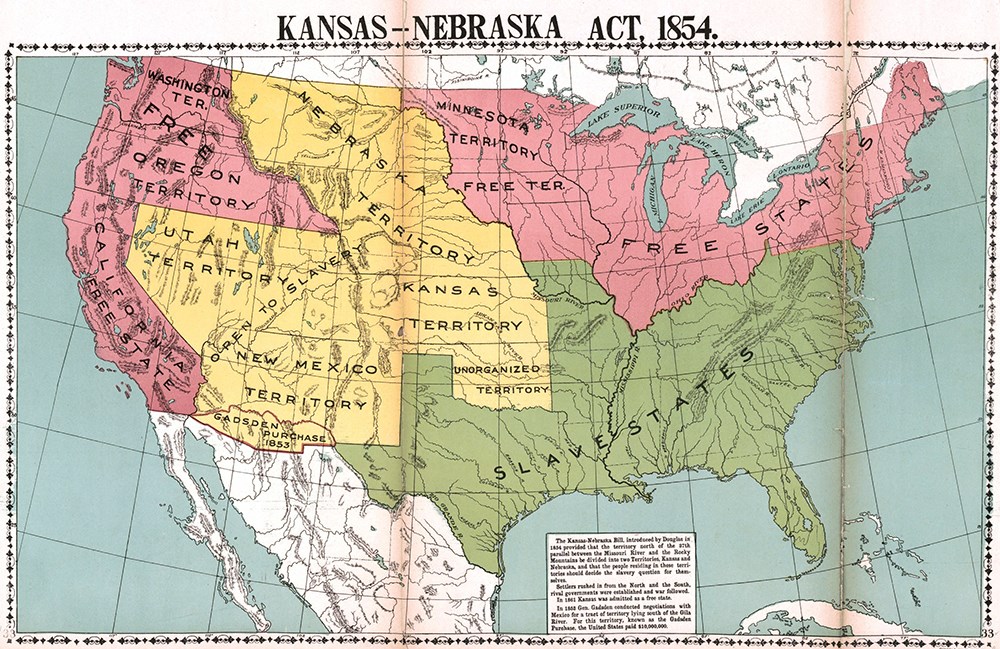

Smithsonian Institution Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Published 1852Prompted by the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act, Harriet Beecher Stowe wrote her best-selling novel. Uncle Tom’s Cabin, which became the second highest grossing book of the late nineteenth century, second only to the Bible. The book inspired many northerners to align themselves with the abolitionist movement and pushed southerners to intensify their defense of slavery. Uncle Tom’s Cabin was a sentimental novel that highlighted the horrors of slavery for a national audience. Focused on provoking emotion in the reader, the narrative centers on the story of Tom, a “good” and religious slave who was sold down river to a cruel master. Tom’s owner abuses him and ultimately orders his overseer to kill him while Uncle Tom attempts to save the lives of other slaves. The numerous religious allusions and dramatic events of the novel captured the hearts of many. For the first time, many northerners were exposed to the horrors of slavery on a personal level, which pushed them towards abolitionism. Outraged by Stowe’s damming portrayal of slavery and slaveholders, white southerners began to publish their own pro-slavery literature. Slaves owners and proslavery writers, threatened by abolitionist works likes Stowe’s, began to move away from defending slavery as a necessary evil to praising it as a mutually beneficial system, a view which had been gaining popularity since the 1830s, thanks, especially, to John C. Calhoun. Uncle Tom’s Cabin further polarized northerners and southerners over the issue of slavery.Kansas-Nebraska Act, 1854Historians William and Bruce Catton described the Kansas-Nebraska Act best when they called it “the most fateful single piece of legislation in American history.” The bill, which became law on May 30, 1854, was intended as a political compromise. However, it further alienated pro- and anti-slavery factions and resulted in bloodshed. Following opportunity and the promise of land ownership, settlers poured into western land acquired through the Louisiana Purchase and Mexican-American War. Some of that land, that west of Iowa and Missouri, quickly became populated and residents called for it to be formally incorporated as a territory. This land, compromised of the future states of Kansas and Nebraska and called the Nebraska Territory, was above the 36°30’ parallel. Following the Missouri Compromise, this new territory would be admitted into the Union without slavery. This would again offset the political balance between free and slave states in Congress. Democratic Senator Stephen A. Douglas proposed a bill to solve this problem. That bill, "An Act to Organize the Territories of Nebraska and Kansas,” became the Kansas-Nebraska Act. Douglas had a particular interest in this territory; he hoped a newly planned transcontinental railroad would take a northern route through Chicago in his home state and pass through Nebraska Territory on its journey west. Douglas was competing with southern slaveholders who wanted the railroad to pass through their own states. To appease the southerners while protecting his own interests, Douglas proposed that the Nebraska Territory be divided into two states: Kansas and Nebraska and that: “all questions pertaining to slavery in the territories and in the new states to be formed therein are to be left to the people residing therein, through the appropriate representatives.” This principle, also known as popular sovereignty, allowed the residents of Kansas and Nebraska to vote on whether slavery would be allowed in their territory. If enacted, this legislation would repeal the Missouri Compromise and opening up the possibility of new slave states being admitted north of the 36°30’ parallel.

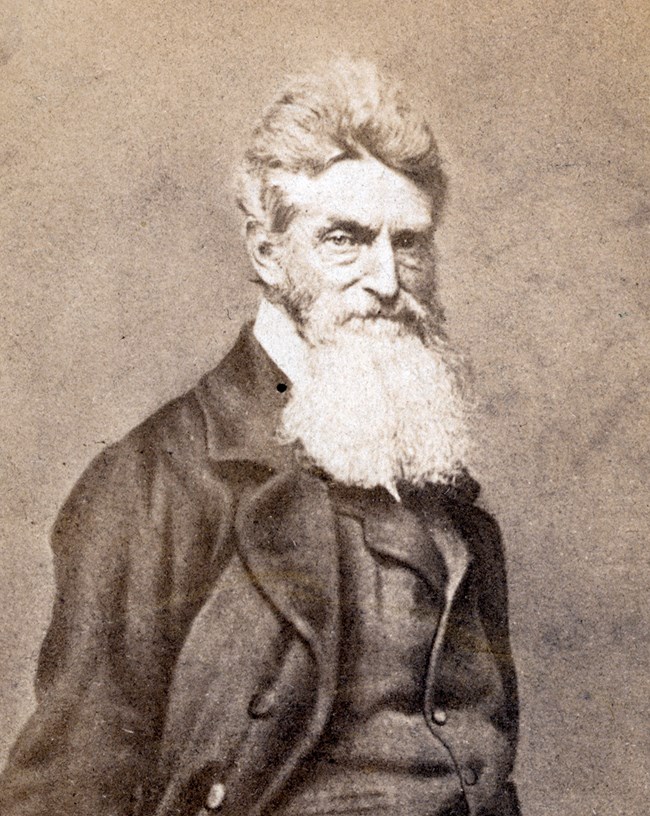

Library of Congress Bleeding Kansas, 1854-1861Despite Douglas’s intentions, the doctrine of popular sovereignty led almost immediately to bloodshed. The term “Bleeding Kansas” refers to the guerilla warfare in the Kansas Territory from 1854 to 1858, in which pro- and anti-slavery advocates killed over fifty people. This violence was a direct result of the Kansas-Nebraska Act, which asserted that settlers in Kansas and Nebraska would decide whether to allow slavery by popular sovereignty. As a result, pro- and anti-slavery supporters flooded into the territory to try to swing the vote in their favor. With these rivals in such close proximity, the stage was set for violent conflict.The majority of settlers in Kansas were small farmers who were interested in the land, not the slavery question. However, the warring factions soon outnumbered these original migrants. Unfair election practices led to the establishment of a pro-slavery legislature. In response, anti-slavery factions established their own rival territorial government in Lawrence, Kansas. On May 21, 1856, a pro-slavery group ransacked the town of Lawrence; they burned a major hotel and other buildings and destroyed the printing presses of an abolitionist newspaper. In retaliation, radical abolitionist John Brown and his allies murdered five pro-slavery men. The armed conflict continued for years, as both sides organized makeshift armies to crusade for their positions. The bloodshed ended with the admission of Kansas as a free state on January 29, 1861, once six southern states had seceded and many of their congressmen had resigned. Both sides, especially the northern abolitionists, used accounts of the violence of Bleeding Kansas in propaganda campaigns to justify their causes; abolitionists used sensational narratives of atrocities as evidence of southern pro-slavery aggression.

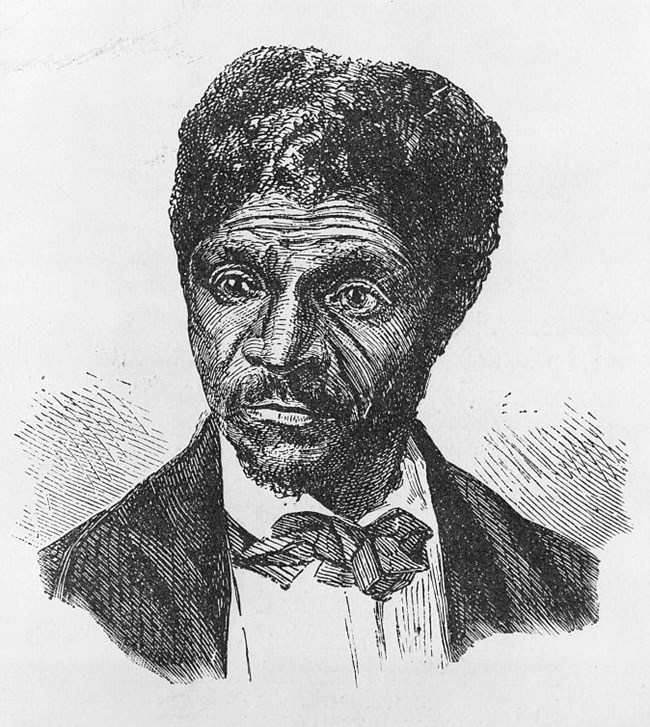

Library of Congress Dred Scott Decision, 1857In his most well know decision as Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, Roger B. Taney claimed that African Americans, "had no rights which the white man was bound to respect; and that the negro might justly and lawfully be reduced to slavery for his benefit. He was bought and sold and treated as an ordinary article of merchandise and traffic.” These words were part of Taney’s majority decision in the case of Dred Scott v. Sanford. In April of 1846, enslaved person Dred Scott sued for his freedom. Scott was born into slavery in Virginia where it was illegal to teach enslaved people how to read and write, thus he was illiterate. His original owner brought Scott to Alabama and eventually Missouri where Scott’s first owner sold him to army surgeon Dr. John Emerson in 1832. Dr. Emerson brought him to his various army posts. Two of those posts were in the free state of Illinois and the Wisconsin territory which prohibited slavery. Scott lived at these posts for several years before his owner moved to Louisiana taking Scott with him. Upon Emerson’s death, his widow decided to hire Scott out, meaning that he would work for someone else, who would pay his owner for his labor. Scott decided to sue for his freedom arguing that his owner had freed him by taking him to a state and territory where slavery was prohibited. The court ruled in favor of Scott, but his owner appealed to the state court which reversed the decision. The case made it to the Supreme Court where the justices ruled seven to two against Scott. Taney’s majority opinion asserted that as an enslaved African American, Scot was not and could never be a citizen. As a non-citizen, Scott had no political rights and could not sue in court. Additionally, according to court, slaves were property and the Missouri Compromise, which banned slavery north of the 36°30’ parallel, infringed on personal property rights and was thus unconstitutional. The Dred Scott case effectively sanctioned slavery as the court declared that Congress could not ban the institution. This decision further divided the Democratic party between northerners and southerners. Northerners were appalled by this the outcome of the Dred Scott case and by white southerners’ positive responses. Growing division among Democrats was a boon to the Republican Party leaders.

Library of Congress Lincoln-Douglas Debates, 1858A series of debates by two Illinois men running for Senate, Abraham Lincoln and Stephen A. Douglas, launched one onto the national political stage. Lincoln lost this election; however, it gave him the national attention he needed to ultimately defeat Douglas in the 1860 presidential election. Throughout the late summer and early fall of 1858, the incumbent Douglas and the challenger Lincoln debated in seven of the nine congressional districts of Illinois. Many of their exchanges focused on slavery and its future in the country, and the two men’s responses had long-lasting impacts on their future careers. Lincoln advocated free-soil policies—halting slavery’s expansion but preserving it where it already existed. Douglas continued to support popular sovereignty and argued settlers in each territory should be allowed to decide on the issue of slavery; this belief became known as the Freeport Doctrine. Southern Democrats felt betrayed by Douglas’s refusal to endorse the expansion of slavery into the new territories. Ultimately, southern members of the Democratic party refused to support his nomination for president and elected their own candidate. The fracture of the Democratic party along sectional lines paved the way for Republican nominee Abraham Lincoln to win the presidential election of 1860.

Library of Congrress John Brown’s Raid, 1859“I, John Brown, am now quite certain that the crimes of this guilty land will never be purged away but with blood.” These are the words Brown left behind for his jailor as he made his way to the gallows on December 2, 1859— an eerie premonition of the coming Civil War. Brown was a life-long abolitionist and no stranger to violence; he and his sons and followers had murdered five pro-slavery men to retaliate for their sacking of the anti-slavery town of Lawrence, Kansas in 1856, and his son, Frederick, was killed in the fighting. After leaving Kansas, Brown spent several years in hiding crafting his master plan to end slavery. He sprung into action on the night of October 16, 1859. He and his 21 followers arrived in Harpers Ferry hoping to seize guns from the federal arsenal located there and to arm the local slaves who they hoped would join them in their war to end slavery. The plan quickly crumbled as local citizens rose up against the raiders. By the next morning, the local militia had arrived, followed by U.S. Marines that afternoon. These combined forces killed or capture most of John Brown’s men the following day, and Brown himself was wounded, but alive upon his capture. Brown was put on trial and convicted of murder, treason, and inciting a slave rebellion. Ultimately, he was hanged for his attempt to incite an uprising.Though the raid lasted less than 36 hours, its impact was immense and abiding. Many northern abolitionists hailed Brown as a martyr. For most white southerners, Brown’s actions confirmed their worst nightmares about the North. Fear of future slave rebellions became even more widespread. Herman Melville said it best when he called John Brown “the meteor of the war.” Abraham Lincoln’s Election, 1860Abraham Lincoln’s election as president in 1860 was the catalyst for southern secession. White southerners reacted immediately; they believed the election of a northern Republican to the highest seat of government meant the death of slavery and their way of life. The election of Abraham Lincoln was a tremendous victory for newly formed Republican party, which was less than ten years old. However, the success of the Republican party would not have been possible without the fragmentation of the Democratic party. The convention to choose the Democratic candidate assembled in Charleston, South Carolina, in April 1860. Their frontrunner was Stephen A. Douglas, a well-known congressman from Illinois. However, his record in Congress, particularly his decision to support popular sovereignty which would allow settlers to choose to ban slavery in their territory, meant that southern Democrats would not support him. He also refused to support a proposed federal slave code for the territories. The first Democratic convention adjourned without a nomination. At a second convention held in Baltimore, Douglas garnered enough support to win the nomination. However, many southern Democrats, angered by Douglas’s nomination, had walked out and formed their own rival convention where they nominated pro-slavery southerner John C. Breckenridge. The nomination of two Democratic candidates effectively ensured that neither would receive enough electoral votes to win the election. The divide intensified when John Bell announced he would be running as a representative of the Constitutional Union Party ticket, which former northern and southern Whigs created hoping to maintain peace by not taking a stance on slavery.

Library of Congress Secession Winter, December 1860-March 1861On December 3rd 1860, outgoing president James Buchanan, in his opening address to the second session of the 36th Congress, proposed an amendment to recognize the “right of property in slaves in the States where it now exists or may hereafter exist.” This amendment became one of the seventy-two proposed amendments designed to stop secession in the winter of 1860. The months following the election of Abraham Lincoln in November 1860 and ending with his inauguration on March 4, 1861 are known as the Secession Winter. During these months, politicians in both the North and South worked diligently to find a compromise that would draw the seven states who had seceded back into the Union and prevent other southern states from following suit.Following the opening of the second session of the 36th Congress, two committees were formed. The Committee of Thirteen in the Senate and the Committee of Thirty-Three in the House of Representatives were formed to develop an amendment that would calm the fears of the southerners and ensure their interests were protected. Men including William Seward, Stephen Douglas, and Jefferson Davis, worked together to develop a plan. Committee of Thirteen member, John J. Crittenden, would propose an amendment that called for the return of the Missouri Compromise 36°30′ parallel as the division for slave and free territories, the preservation of slavery in Washington, D.C. and federal institutions in the South, protection of the right of slaveowners to travel in the north with their slaves, strengthening of the Fugitive Slave Clause, and the prohibition of Congress interfering with slavery in the states. Though this amendment, known as the Crittenden Compromise, failed to become law, its components reflect most of the amendments proposed during the Secession Winter. Coming from northerners and southerners alike, these amendments attempted to persuade southerners that the Union was intent on protecting their right to own slaves. Another of these conciliatory amendments nearly became the 13th Amendment to the Constitution. This amendment, the Corwin Amendment, was sponsored by William Seward and emerged from the Committee of Thirty-Three which was chaired by Republican Thomas Corwin of Ohio. The Corwin Amendment asserted that "no amendment shall be made to the Constitution, which will authorize or give to Congress the power to abolish, or interfere within any State, with the domestic institutions thereof, including that of persons held to labor or service by the laws of said State." This amendment essentially prohibited Congress from interfering with slavery and gave the states the power to regulate slavery as they saw fit. Though it was a major concession to the South and guaranteed the possibility of slavery’s expansion, the Corwin Amendment passed both the House and Senate and five states ratified it before the outbreak of hostilities at Ft. Sumter ended all hopes of appeasing the South. This first 13th Amendment shows the great lengths politicians went to reunite the nation in the winter of 1860 and its failure shows the south’s determination to follow through with secession.

Library of Congress Fort Sumter, 1861Confederate forces fired the first shot of the Civil War at Fort Sumter in Charleston, South Carolina on April 12, 1861. After South Carolina left the Union, the United States soldiers stationed in Charleston Harbor at Fort Moultrie on Sullivan’s Island moved to Fort Sumter. Located across the harbor from Fort Moultrie, Fort Sumter was a more defensible position since it was isolated on a small island with no other residents. In the state’s Declaration of Secession, South Carolina’s delegates called for the United States to turn over all federal property in the State, including Fort Sumter. President James Buchanan refused. Weeks went by, and the U.S. soldiers in Fort Sumter began to run out of supplies. President Lincoln was inaugurated in early March, and he decided to resupply the fort without providing reinforcements or firing on the other installations to avert hostilities. The Confederate government would not permit the resupply expedition, and General Beauregard ordered the small group of soldiers to vacate. The federal commander of the fort, Major Robert Anderson, refused and at 4:30 am on April 12, Confederate troops opened on Fort Sumter. The bombardment lasted until April 13, when Major Anderson agreed to evacuate. Two days later, President Lincoln called for 75,000 volunteers to put down the rebellion. Within two months, four more states seceded. The Battle of Fort Sumter marked the beginning of four and a half years of immense bloodshed that would forever change the United States through the destruction of slavery. |

Last updated: September 15, 2023