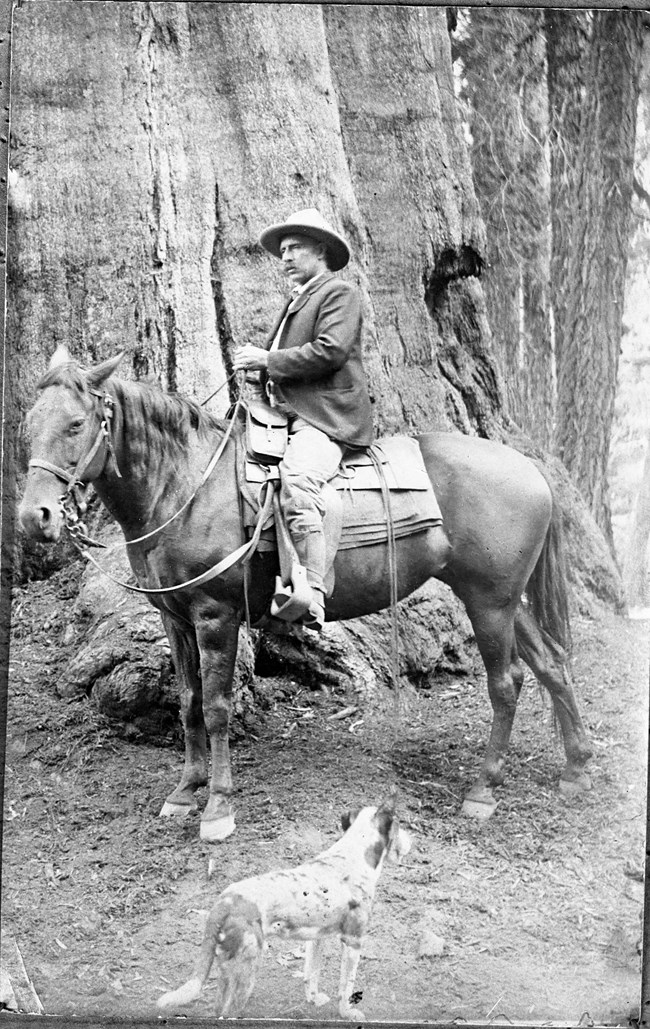

NPS Photo A Life Changed by SequoiasWalter Fry’s life was intertwined with giant sequoias for a half-century. Thirty of those years were in service to Sequoia National Park and General Grant National Park, the predecessor of today’s Kings Canyon National Park.

NPS photo The First Civilian Superintendent of Sequoia and General Grant National ParksFry’s career with the parks began in July 1901, when he signed on as road construction foreman for Sequoia National Park. Over the next three summers, working under the direction of army officers, Fry led on-the-ground efforts to repair and re-establish the Colony Mill Road, which was the first road into the Giant Forest. In July 1905, Fry became a civilian park ranger, one of a handful appointed to assist the cavalry troops then in charge of the parks. From this position, he became the chief park ranger in 1912, a position that made him acting superintendent of the park during the winter months when the troops were not present. When the Army gave up caretaking the parks in 1914, the choice for civilian superintendent was a clear one. Fry became superintendent of Sequoia and General Grant National Parks, a position he would hold for the next six years. Fry became an employee of the National Park Service when the agency was created in 1916, but it was not until the World War I had ended that the new agency began to make changes in how the parks were run. Sequoia’s moment of change arrived in the summer of 1920, when Director Steven Mather replaced him with a man of his own choosing: John White. Yet another life chapter began as Fry shifted jobs, becoming a U.S. Commissioner, or federal magistrate judge, in the parks. White recognized his worth immediately: "It would be almost impossible to overstate the affection and esteem in which Judge Fry is held by both Park employees and visitors. He has been able to enforce park regulations with such sympathetic insight into the needs of visitors and residents that the enforcement has won friends for the Park Service." He retained this responsibility for the next 22 years, eventually pre-siding over more than 200 misdemeanor-level court cases within the two parks.

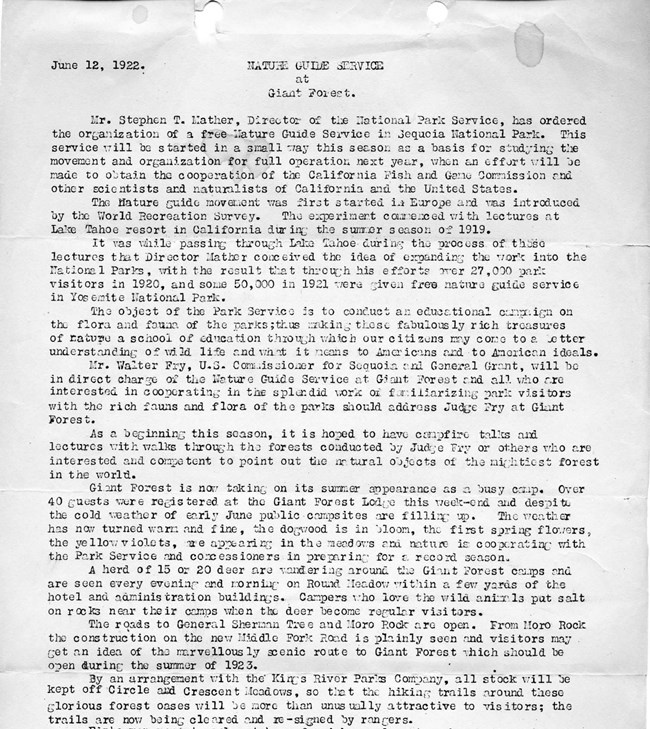

Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks Archives A Lasting LegacyThe magistrate job did not weigh heavily on Fry’s time, and he used the resulting opportunity to open another life chapter. In 1922 Fry became involved with what may have been his most enduring contribution, the first Nature Guide Service at Sequoia National Park. He led nature walks, wrote nature bulletins, organized the first public museum in Sequoia National Park (housed in a tent), and spoke often at campfire programs. Although not working directly for the parks, he influenced the park by influencing visitors, passing on his deep appreciation of the place. The Nature Guide Service was the foundation of the ranger programs and talks that millions of visitors have participated in at Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks over the decades. In the late 1920s, Fry worked closely with Superintendent White to draft the book Big Trees, published by Stanford University Press in 1930. The contents of the book reflected Fry’s careful observation of nature. For example, earlier in his career he had caged individual sequoia cones in wire screen and, each year for twenty years, had recorded how many seeds fell out of each cone. Even after Fry retired in 1930, at age 71, Fry offered walks, wrote nature bulletins and organized visitor centers; the thousands of visitors he touched in turn became ambassadors for the landscape he loved so much. In the 1930s the park published a volume of his “nature notes” that captured important stories of the park’s earliest days. Fry died in 1941, aged 82 years. He remained active until the end, leaving his home for the hospital only three days before he passed away. Park rangers carried his coffin to the grave. |

Last updated: September 13, 2023