|

.

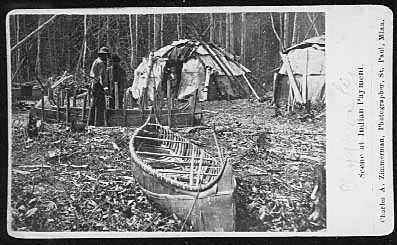

Charles Alfred Zimmerman, Minnesota Historical Society Dakota and Ojibwe

Children were essential to the survival of the tribe. During the summer while their parents were out hunting for food or sewing clothes what did the children do? They did what children do today. They played games. But they played games such as throwing a spear through a rolling hoop, and catching a bundle of cedar leaves on a pin. Although the games were fun and provided hours of entertainment they also taught valuable skills such as teamwork, endurance and hand-eye coordination, skills necessary for hunting. Described below is a popular Native American game for you to try at home. Ball & Triangle: To make this game cut a triangular shaped piece of birchbark or wood. Attach one end of a string to the wood and the other end to a small ball. Drill a hole in the wood slightly larger than the ball. The object of this game is to drop the ball through the hole in the wood. What kind of life skills could you learn from this game?

Fur TradeIn 1804 two rival fur trade companies, the North West and XY, sent traders to build wintering posts in the St. Croix Valley. John Sayer of the North West Company, based in Montreal, Canada, built a trading post along the Snake River. Michel Curot of the XY Company, also based in Montreal, built his trading post along the Yellow River. Both rivers are tributaries of the St. Croix. During the next several months Sayer and Curot competed with each other to see who could acquire the greatest number of animal pelts from the local Ojibwe Indians. Beaver was the most desired pelt, but they also accepted muskrat, mink, otter and others. In many ways fur traders were traveling salesmen. Sayer and Curot brought with them trade items they believed the Ojibwe would want. Things like cooking pots, axes, guns, tobacco and beads. The money used by the traders had no value to the Ojibwe, so the Ojibwe used animal pelts, wild rice and meat to purchase what they wanted. This came to be known as the barter system and is still used in some parts of the world today. Why were Sayer and Curot so interested in beaver pelts? Centuries ago, hatmakers in Europe discovered that beaver fur made the finest felt for making hats. In England and France beaver hats were very expensive. The price of one beaver hat might represent three to six month's wages for the owner. Because of their cost, beaver hats became symbols of status for wealthy people. You might think of them as a top of the line computer with all the extras or a fancy car. What are some other examples of status symbols at your school? What happened to the beaver hat? By the 1840's beaver were depleted from most of their former habitat, they had been over trapped. It was also about this time that silk was introduced from China. Silk produced a more durable hat than beaver felt and soon became the material of choice among European hatmakers. This change in fashion spelled the end of the fur trade as a major industry in North America.

Minnesota Historical Society A River Drive

|

Last updated: February 13, 2025