|

Contents

|

"A City Designed as a Work of Art": By Pamela Scott ON 6 January 1902, nine days before the Senate Park Commission exhibit opened at the Corcoran Gallery of Art, Glenn Brown and Charles Moore spoke at a meeting of the Columbia Historical Society. Their goal was to prepare Washington's historically minded community to accept imminent changes planned for the city. In his illustrated lecture, "The Making of a Plan for Washington City," Brown drew on his professional education as an architect and his avocation as a local historian to recount Peter Charles L'Enfant's sources for his plan of Washington. He enumerated the maps of the eleven European cities Thomas Jefferson sent L'Enfant on 10 April 1791, but singled out Paris and London as the "capital cities of the two most powerful countries of the world in L'Enfant's time." Paris was L'Enfant's native city and Sir Christopher Wren's 1666 plan for rebuilding London exhibited key elements of L'Enfant's Washington: long, broad boulevards and public squares or circles from which streets radiated. [1] After Brown set the historic stage, Moore, Michigan Senator James McMillan's secretary, gave a lecture describing the Senate Park Commission's proposed improvements to all parts of the outlying areas of the District of Columbia. Moore, defender and apologist of Congress's administration of Washington's municipal affairs, toured his audience around the city's outskirts, interweaving recent public services (sewers, water supply, purchase of park lands) with the proposed parkways, driveways, parks, and land reclamation projects. Throughout his lecture Moore emphasized Congress's preservation of the area's natural beauty for future generations. He concluded by emphasizing the honesty, efficiency, and non-partisan "enlightened spirit" with which Congress dealt with District of Columbia affairs. [2] Brown wanted L'Enfant's Paris and nearby royal gardens to be major influences on the original design for Washington because the Paris, Versailles, and Vaux-le-Vicomte of 1901 were major influences on the Senate Park Commission's "revival" of L'Enfant's plan to be made public in just a few days. He wanted Wren's London and near-by country estates to be prototypes because he wanted English (and hence Anglo-American) traditions to have also been part of the city's original design process. Moore wanted to reassure his local audience that city residents were to benefit materially from the Senate Park Commission's plan, their substitute "city council" in the form of the House and Senate Committees on the District of Columbia, responding to their needs and wishes. Moore, writing nearly three decades after the event, likened Paris—"a city designed as a work of art"—to the Senate Park Commission's vision for the Mall. [3] Brown and Moore were an accomplished public relations team who had been at the epicenter of Washington's modernization for the past several years. As its secretary, Brown had galvanized the American Institute of Architects to take an active role in Washington's future development, beginning with its 1900 annual meeting. Moore, trained as a journalist, had come to Washington from Detroit in 1889 with the newly-elected McMillan and worked closely with him on improving fundamental city services after the senator was appointed to the Committee on the District of Columbia in 1891. Brown's and Moore's joint goal on 6 January 1902 was to convince Washingtonians that the Senate Park Commission's plan was the perfect solution to the capital's future growth because it revived the city's original design and conserved large parts of the surrounding countryside where subdivisions were rapidly being laid out on former farmland or country estates. Their strategy was imbedded in the history of Washington's founding and the acknowledged beauty of the federal city's original design. L'Enfant's plan (pl. I) was well-known locally in the 1890s because it had been periodically discussed in Washington newspapers and even national journals. In 1887 Army engineer Colonel John Wilson, head of the Office of Public Buildings and Grounds which had legal possession of L'Enfant's fading manuscript, persuaded the Coast and Geodetic Survey to make a facsimile. This effort led to extensive research about the plan's origins, much of which was duly noted in the Evening Star. The American Architect and Building News considered Washington reporter Frank Sewell's articles on Washington's public buildings (which mentioned L'Enfant's plan) important enough to reprint in its 13 February and 7 May 1892 issues. At a time when both the city and federal governments were discussing new buildings to serve a variety of functions—a municipal building, a public library, a judiciary building (that included rooms for the Supreme Court), a government printing office, an auditor's office, a geological survey, and even a national university—Sewall was urging that they be grouped coherently on the south side of Pennsylvania Avenue between the White House and Capitol. In 1900, North Dakota Senator Henry Clay Hansborough, a member of the Committee on the District of Columbia, praised the idea of placing public buildings south of Pennsylvania Avenue, especially if they were surrounded by parks and brought the Mall up to the avenue. Moreover, "almost a unanimity of opinion prevails in the House for putting public buildings hereafter south of Pennsylvania Avenue." [4] As part of his study of the U.S. Capitol during the early 1890s, Brown had carefully examined the characteristics of L'Enfant's plan, considering himself to be both its champion and resurrector. The opening chapter in the first volume of his History of the United States Capitol (1900) is a slightly shortened version of his "The Selection and Sites for Federal Buildings," published in the Architectural Review in 1894. Brown's thoughtful look at L'Enfant's plan and the many reports and correspondence relating to it led to him to conclude that the "the more the scheme laid out by Washington and L'Enfant is studied, the more forcibly it strikes one as the best." In both 1894 and 1900, Brown likened the Mall to the Champs Élysées, his only discussion of L'Enfant's sources prior to his championing of the Senate Park Commission plan before the Columbia Historical Society in January 1902. As early as 1894, Brown criticized the random placement of federal buildings in Washington during the nineteenth century, claiming they depended "on cost, influence, whim, or the advice of men in no way prepared to advise." L'Enfant's 1791 plan offered a model to counteract the continuing fragmentation that characterized post-Civil War placement of Washington's public buildings. [5] On 13 December 1900 Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr., who was to be the landscape architect on the Senate Park Commission, concluded his paper delivered at the AIA meeting, "Landscape in Connection with Public Buildings in Washington," with the point of view that was to become a fundamental tenet of the commission and its adherents:

During the next few years, Washington as L'Enfant's active design partner grew from a conviction to a propaganda tool, a patriotic shield to fend off potential critics of the Senate Park Commission's radical redesign of Washington's Victorian monumental core. Thomas Jefferson's role in the federal city's design, (arguably more important than Washington's from an examination of extensive surviving documentation) was rarely mentioned although his role in the city's founding was acknowledged. The Federalist Washington was the political ancestor of early nineteenth-century Republicans then in power; the Democratic-Republican Jefferson's role was undoubtedly invoked to garner support among contemporary Democrats in addition to maintaining some historical credibility. With the collaboration and advice of the Senate Park Commission, Moore wrote a two-part article for the February and March 1902 issues of Century Magazine entitled "The Improvement of Washington City" to coincide with publication of the commission's report entitled "The Improvement of the Park System of the District of Columbia." Moore began with the history of the founding of the federal city:

Moore concluded his overview by noting that "Washington and Jefferson not only adopted L'Enfant's plan, but so long as they were in power they protected it from perversions. . . and by the time these two worthies had passed from the scene the main features of the original scheme were fixed beyond possibility of loss, although not beyond neglect and temporary perversion." Yet when Moore spoke before Washington's historians in January 1902 he was unwilling to deviate from the evidence of government records. "Two plans were submitted by the young architect and rejected. The third was accepted, and although the original development and general scheme belong alone to L'Enfant, both Washington and Jefferson made known their views on the subject." [7] Moore's articles and lectures delivered by Brown, Moore, and members of the commission were very effective, calculatingly so. On 28 August 1901, New Yorker Charles F. McKim reported to Chicagoan Daniel H. Burnham (the two architect members of the Senate Park Commission) the outcome of a meeting with Secretary of War Elihu Root:

Section four in the 13-page introduction to the commission's report presented the city's original design history in terms of what Burnham, Olmsted, and McKim wanted it to be in order to coincide with the major elements of their own plan:

McKim, very much an architect who championed the role of architects, may not have believed as fervently as the other commission members in Washington's prominent role in the actual design of the city. On 6 April 1901 Root had introduced the commission to President William McKinley, who "received us cordially and spoke, without hesitation, in favor of preserving the works of Washington's time," McKim wrote a few days later. "I trust you are not out of sympathy with your friends who are struggling in the cause of Peter Charles L'Enfant, he appended in a postscript to a letter sent to President Theodore Roosevelt on 20 March 1904. [10] Burnham, however, was a true believer. After Roosevelt became embroiled in the debate about locating the Department of Agriculture Building, Burnham wrote Secretary of Treasury Leslie M. Shaw on 24 March 1903 that:

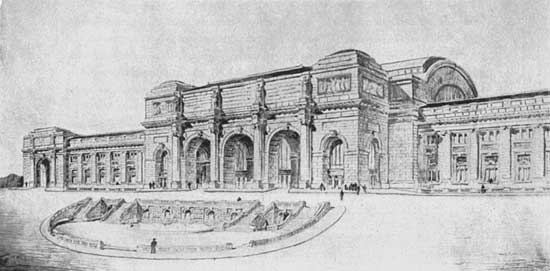

On 9 August 1903 Burnham wrote Secretary of Agriculture James Wilson: "I have the honor to send you a copy of the general plan, made by the Senate Commission, on which I have marked the true axis referred to. This plan carries out General Washington's, which is L'Enfant's." Burnham continued to gather evidence to support his thesis. "By-the-by! I was told in Pennsylvania a few months ago," he wrote Olmsted the following November, "that there is a small town in the vicinity of Connellsville, which was laid out by General Washington when he was a young man, and that it has the same system of radiating streets as the City of Washington. This, if true, will prove that the plan of the Capital of the country is Washington's own and not Major L'Enfant's. I am going to investigate it more carefully." In testimony before Congress on 12 March 1904, Burnham declared: "We examined the documents, among others the well-known L'Enfant plan, which was prepared under the direction of and in participation with General Washington. Washington himself selected this location and then employed L'Enfant to carry out his ideas." [12] How did the commissioners' understanding of L'Enfant's plan, and the political era that produced it, influence their own designs for Washington's monumental core during 1901? When he spoke before the Columbia Historical Society in January 1902, Brown knew L'Enfant's Paris was not the same city Burnham, Olmsted, and McKim had visited with Moore during the summer of 1901. [13] Brown's lecture, therefore, abounds in contradictory statements as he tries to resolve the conundrum of L'Enfant's multiple sources of inspiration. Paris's "numerous small squares and the parked way of the Champs Élysées may have suggested and probably did suggest the many small parks as well as the treatment of the Mall, which he adopted in his plan" (fig. 1). Brown's brief account of Versailles focused on the landscape setting André Le Nôrte created for it from 1661-1668:

Yet, a few sentences earlier: "The Mall, as the grand garden approach to the Capitol, would naturally have suggested itself from a study of the Champs Élysées and of the more beautiful garden approach to Versailles." [14] To appeal to those who opposed Beaux-Arts classicism and favored "American" sources for civic design, Brown emphasized that the "most unique a distinctive feature of Washington, its numerous focal points of interest and beauty from which radiate the principal streets and avenues was not suggested by any city of Europe." He sought and found two American antecedents—Annapolis and Williamsburg—that he stated "influenced [George Washington] in approving and modifying the scheme submitted by L'Enfant." Annapolis's "two focal points from which several streets radiate," Brown believed, had been taken from Wren's plan of London, and Williamsburg "had a mall, a dignified tract of green around which imposing buildings were grouped and toward which the principal streets converged." L'Enfant himself had almost surely been to Annapolis because it was a major Chesapeake Bay port near Washington. It is unknown if he ever saw Williamsburg; he was a prisoner of war on Haddrel's Island, South Carolina, when the French troops engaged in the battle of Yorktown, Virginia, in 1781. In April 1902, Buffalo architect George Cary chastised those who were "narrow minded enough to criticize the [plan] and to say that it is Frenchy. . . should remember that in beautifying the city of Washington along the lines adopted by the special park commission, that body is simply carrying out the plans of Maj. L'Enfant [15] A month after the Senate Park Commission was formally created on 19 March 1901, and while they were in the midst of preparations for a summer trip to Europe, Chicago reporter William E. Curtis arranged for them to visit Chesapeake Bay towns and plantations. From 20-24 April, Burnham, Olmsted, McKim, Moore, and Curtis, accompanied by several government officials and prominent businessmen, visited seven Virginia sites. "Williamsburg had its lesson," Burnham wrote his wife on 24 April, "for here in outline is the plan of the Mall in Washington with the Capitol at one end of the broad parkway; the College of William and Mary at the other end of the main axis, and the Governor's Palace at the head of the cross-axis, a location similar to that of the White House." Three weeks later the same party spent a day visiting Annapolis and two Maryland plantations. The immediate political purpose of these two trips was to reinforce the link between George Washington, Anglo-American planning traditions, L'Enfant's plan, and the Senate Park Commission's initiatives as well as to forestall criticism of a European bias in their thinking. [16] The relative contributions of the European and American journeys made by the Senate Park Commission vary greatly: some specific experiences that impressed them all were recorded in correspondence and drawings, others can be inferred, and yet others were so synthesized into their general design tenets as to be totally absorbed. The following detailed examination of visual and textual documents produced during, or relating to, the ten months when the Senate Park Commission was actively designing, seeks to clarify these varied contributions. Congressional committee report #1919, "Commission to Consider Certain Improvements in the District of Columbia," dated 18 January 1901, was the first formal step towards establishing the Senate Park Commission. It summarized Congress's accomplishments during the 1890s (which coincided with most of McMillan's tenure on the District committee), claiming they "provided the means for the artistic development of the District of Columbia in a manner befitting the capital city of the nation." From the purchase of Rock Creek Park (1890) to the adoption of a permanent system of highways for the entire District of Columbia (1898), these projects "bertoken[ed] the desire and intention of Congress to carry out the original idea of making Washington a beautiful capital city." [17] The purpose of the Senate's proposed commission was to "get up a comprehensive scheme "a plan to work to," according to Olmsted's notes of the 19 March 1901 Senate subcommittee hearing attended by himself, Burnham, and an AIA committee. Olmsted noted that "Mr. McMillan made a brief, clear statement from which it appeared that the subject which most interested him was parks although placing of public buildings was part of the project." Olmsted (and other attendees) recognized that the chief difficulty was that the "diverse authorities over different parks and over public buildings, grounds and statuary" was not just confined to the jurisdictions of different executive departments, but extended to congressional committees as well. To get a consensus of what constituted an "artistic" plan for Washington's future development, a matter of taste and therefore peculiarly personal and strongly felt, would be very difficult. "The sub-committee [consisting of McMillan and New Hampshire Senator Joseph Gallinger]," Olmsted concluded, "does not know just what it wants to do not how to do it." [18]

Burnham and Olmsted met with McMillan and Moore on 22 March and "agreed that report and plans must be as general in terms as possible so as not to tie things up too tight and so as not to offer many points for attack, but I thought that in dealing with Mall and public buildings we should be forced to be somewhat specific. Mr. B. did not see why we should." By 27 March when McKim had accepted Burnham's invitation to be the Park Commission's third member, Olmsted was already at work asking Moore two days earlier to obtain a set of ordinance survey maps of London and its suburbs "with the parks and other public spaces outlined and so marked as to indicate the authority in control of each." Olmsted had access in Boston to a map of the Paris parks. [20] On 29 March Burnham wrote Olmsted that the first business of the commission's initial meeting scheduled to begin on 6 April would be to "organize" and "to comprehend the work, its scope and limitations." He stressed that the three members must "fix the rules governing our official actions" and that not even a draftsman should be hired until they had decided on the division of responsibilities. Although many contributions of individual members can be identified, much of their work was a team effort. Burnham wrote a second note to Olmsted the same day: "I am trying to arrange for a run across the water this summer. Will you go and will you be able to leave by the middle or end of June? I am writing to Mr. McKim by this post, asking the same questions. We can decide when we meet." Thus, almost immediately after the establishment of the commission, Burnham thought in terms of European inspiration. [21] The commissioners met for three days beginning on 6 April when they visited Arlington National Cemetery and the following day spent the "morning on the Potomac," lunched at the Library of Congress, and in the afternoon and the following day advised the Grant Memorial Commission. In 1904, in testimony before Congress on the work of the Senate Park Commission, Burnham recalled its initial "optical survey." "We encircled the city on the hills, spending a great deal of time, keeping our minds open as far as possible, without going to the documents or attempting to examine what had already been done. In this way we expected to become familiar without prejudice from anything that had already been done with the situation." McKim, immediately after his return to New York, wrote: "If half of what is talked of can be carried through it will make the Capital City one of the most beautiful centers in the world. The work of education still requires many years, but the essential thing. . . is to bring about a general plan." On 10 April Olmsted hired James G. Langdon, a landscape architect in his office, as the commission's first draftsman and three days later dispatched him to Washington. Langdon's drawings produced during the next two months are the best record of what the Senate Park Commission accomplished during its initial meetings. [22] Langdon's first map for the use of the commission members was of the entire District of Columbia, compiled from ones obtained from the Corps of Engineers, Coast and Geodetic Survey, and District Commissioners (pl. III). This lithograph showed graphically the results of all current legislation concerning the city, with color coding indicating the extent and jurisdiction of all large plots of land in public and quasi-public hands. The War Department controlled the Mall and East and West Potomac Parks and all the public reservations—the squares, circles, and parklets—within L'Enfant's original city boundaries. It was also responsible for the Soldiers Home, Washington Barracks (formerly the Arsenal), Reservoir, and Arlington National Cemetery. The District Commissioners, the Interior Department, the Navy Department, the Smithsonian Institution, Gallaudet College and others controlled scattered tracts throughout the city. Langdon overlaid on this map the 1898 version of the "permanent system of highways," developed over the previous decade to extend L'Enfant's grid streets, diagonal avenues, and public circles into all areas between Florida Avenue (Boundary Avenue before 1890) and the District of Columbia-Maryland line. The third important documentation that Langdon included on his map were the streets and city squares that Congress had determined during the 1890s might be used for railroads. Public schools were indicated by circles because recreational facilities for schools were one of the many local issues the Senate Park Commission was to address. The boundaries and street patterns of Washington's 101 subdivisions that had been laid out during the previous half century were also indicated on Langdon's map. Thus, the Senate Park Commission designers had in one place valuable information about what public lands were available for outlying parks (and which federal agency was responsible for them) and where future circles, squares, and avenues would be. Moreover, they knew where Burnham's recently commissioned Baltimore & Potomac (hereafter B&P) Railroad station could legally be located. Langdon identified the possible railroad corridors along existing tracks in the city's southwest, southeast, and northeast quadrants and the entire width of the Mall between 6th and 7th streets. A railroad bridge parallel to Long Bridge carried existing tracks across the Potomac River that originated southeast of the city (crossing the Anacostia River at M Street SE) and ran along Virginia Avenue SE and Virginia Avenue SW until they made a 130 degree turn at the intersection of Maryland Avenue SW, a block south of the Mall. Tracts of land comprising several city squares were proposed at three points along this route for railroad expansion: at the landfall of Long Bridge at 14th Street SW; south of the intersection of Maryland and Virginia avenues between 6th and 10th streets SW (the Senate Park Commission initially located the B&P station partially within these boundaries); and between Virginia Avenue, South Capitol, M, and 2nd streets SE. The land for possible railroad expansion in the relatively undeveloped northeast sector was concentrated along the corridor of tracks that served the Baltimore & Ohio (hereafter B&O) station at New Jersey Avenue and C Street NW and its freight depot in Eckington, a northeast subdivision just beyond Florida Avenue. A wide swath from North Capitol to 2nd Street NE gradually narrowed above Massachusetts Avenue diminishing to just a corridor above R Street. In June and July 1901, B&P railroad president Alexander Cassatt (who had just acquired control of the B&O railroad) chose to place his new Union Station within this precinct. Legally he could have built a new station on the Mall; the Park Commission wanted the station south of the Mall but was delighted that Cassatt found it advantageous to locate it on Massachusetts Avenue NE. For a brief time in October 1902, when Congress could not agree on a site, Cassert was willing to have the station south of the Mall: "he says he wants this thing settled now without any further delay," Burnham reported to Curtis. [23] Several preparatory drawings for the Senate Park Commission plan have survived among McKim's papers in the New-York Historical Society. On 10 April 1901 Burnham wrote Olmsted suggesting that they "begin to lay out the work between the capital Obelisk and the dome of the Capitol on a large scale," that is, that they make drawings of a large size. Among McKim's papers are two Mall plans dated 27 April 1901 which he acknowledged receiving (along with photographs of the Mall) from Langdon on 2 May. The base plan isolated the Capitol grounds and the two blocks directly east of it; the Mall and the pertinent areas north and south of it roughly between Pennsylvania and Maryland avenues; the White House complex including greater Lafayette Park; and, several blocks between the White Lot (now called the Ellipse) and the Potomac River. In these areas, streets and buildings were shown in detail but East and West Potomac Parks, the Tidal Basin, and Hain's Point were shown in outline only, probably because the commission was not yet ready to concentrate on these areas. [24] On the first 27 April plan (fig. 2) Langdon inserted the elevations of the Mall along nine north-south lines and at several other points including within the Mall-Pennsylvania Avenue triangle (later called the Mall Triangle by the Park Commission), east of the Capitol, and at the foots of 17th through 23rd streets, NW. The disparity in height between the north and south sides of the Mall was considerable, the south side varying from 22.8 feet at 7th and B streets, SW, to 37.3 feet at 14th and B streets, SW, while the corresponding intersections on the Mall's north side ranged from about 6.5 to 7 feet above sea level. The elevation along the Mall's center line gradually rose from about 20 feet at 7th Street to 24.5 feet at 14th Street; the Washington Monument sat exactly 40 feet above sea level on the summit of a conical mound, its grounds to the west falling rapidly to 8.5 feet.

On April 30, apparently in response to receiving his copy of this 27 April 1901 plan, Olmsted wrote Glenn Brown asking him to send Langdon a Coast and Geodetic Survey facsimile of a map that dated from about 1798 and showed buildings only on the Mall's south side. Writing to Langdon on 4 May about this map, Olmsted noted that it was "not the L'Enfant Plan of 1791 and is one which Mr. Brown had not discovered in his researches," but was one Olmsted had lent Brown. Soon after 16 May Olmsted investigated this map further and concluded that the "differences may be the fancies of the engraver," but the episode shows how carefully the team investigated L'Enfant's (and his contemporaries') intentions as they conceptualized the new plan. With the exception of the B&P station built at 6th Street, NW, in 1872, all of the Mall's nineteenth-century buildings were scattered irregularly along the high ridge on its south side. The earth works necessary to level the Mall would be a considerable undertaking, an issue that the Senate Park Commission seems to have addressed immediately. [25] Langdon's second Mall plan (pl. V) dated 27 April 1901 depicts the effects of reinstituting L'Enfant's Mall and accommodating some proposed new buildings. The Park Commission maintained the existing cross streets but divided the Mall into seven east-west zones, the outer one colored green but presumably planned for buildings in landscaped settings. This building zone fronted walkways backed by a grove of five rows of trees planted in a formal quincunx pattern in a 225-foot-wide swath. These three zones framed an open, central space 350 feet in width colored yellow rather than green to indicate that a boulevard or carriageway was initially considered rather than a greensward or parkway. (In 1900, both Colonel Theodore Bingham of the Corps of Engineers and Olmsted had suggested running a broad carriageway down the Mall's center.) A major purpose of Langdon's drawing was to determine the effect on existing buildings and adjoining private property if the Mall were to be realigned on the Washington Monument with each of its sides equidistant from a central axis. It demonstrated that the government would have to purchase all the squares facing B Street South between 6th and 15th streets, if both sides of the realigned Mall were to be equal in width. [26] Langdon's second 27 April plan also showed a proposed major cross axis, a graveled boulevard, between 7th and 9th streets in the same location where L'Enfant had proposed breaking up the Mall's great length by placing a water element on its north side. This blueline also placed Burnham's new B&P railroad station south of the intersection of Maryland and Virginia avenues, SW, a logical early decision because the tracks already were laid through the intersection and it could be legally located on part of it. Another result of the Senate Park Commission's April meeting recorded on the 27 April blueline was the proposal to incorporate the land within the wide triangle facing the Mall formed by Virginia and Maryland avenues (about half the Mall's length) to function as a plaza vestibule for the station. Three new buildings for the Department of Agriculture were penciled in on the Mall's north side between 12th and 14th streets, NW; the 2 March 1901 congressional appropriation stipulated that they be "erected on the grounds of the Department of Agriculture" which spanned the Mall's width between these two blocks. Dark pencil hatching of several blocks north and south of the Mall and east of the Capitol may mean that these areas were already being considered for an expanded public precinct. McKim wrote Moore on 10 May noting that Langdon's "plans...have been most useful" and that when the commissioners next met they would be "in a better position to discuss [the treatment of the Mall more] intelligently than was the case on our last visit." Their next meeting began on 15 May with their second Chesapeake Bay trip to Maryland sites followed by four days of intense work on the Mall's redesign. The results of that charrette are recorded on a plan dated 3 June 1901 but seem to have been preceded by a set of unsigned and undated figure-ground (high contrast black areas placed on a light background) studies of Washington's monumental core made on small printed maps of the District of Columbia. These two altered maps were probably made by Olmsted in response to Langdon's 27 April Mall plans that recorded the commission's "what if's". When the tin case of plans that Olmsted planned to take to Europe did not arrive in time, he sent for several printed maps of Washington, apparently his favored method of quickly recording his thoughts vis-à-vis actual conditions. Moreover, Olmsted used the same graphic figure-ground convention for the plans of parks in urban settings that his firm contributed to in the Senate Park Commission's report published in January, 1902. Olmsted may have brought the two surviving figure-ground studies to the commission's May meeting; they are preserved among McKim's papers. The first of Olmsted's figure-ground drawings (fig. 3) has inked in black the Mall and President's grounds, in grey the larger public reservations, in red the smaller ones, and outlined in green Rock Creek Park, the Soldier's Home, the Reform School and other outlying government properties that encompassed large land areas. This study graphically illustrated the concentrated mass, but irregular configuration, of Washington's L-shaped monumental core in 1901. The spatial homogeneity of the Mall's east end had first been compromised in 1808 when the canal was cut across it at 4-1/2 Street and again when the Botanic Garden was laid out at the foot of Capitol Hill in 1823, three years after Congress granted the site. The canal was slowly filled in during the 1870s and in 1872 the B&P railroad tracks were laid along Sixth Street. The east end of the Mall was further interrupted when Missouri and Maine avenues were inserted parallel to Pennsylvania and Maryland avenues for the two blocks between 4th and 6th streets.

The black inked areas on Olmsted's second undated figure-ground study (frontispiece) outlined not just the accepted monumental core but expanded its boundaries to include the squares framing the Capitol grounds; the triangle between the Mall and Pennsylvania Avenue; the entire X-shaped crossing of Virginia and Maryland avenues south of the Mall; the residential blocks facing the east and west sides of Lafayette Square; and, several privately held blocks on both sides of the Mall's east end where it joined the Capitol grounds. If the blacked-out blocks do indeed represent proposed expropriation of private land for public use (as they seem to), the Senate Park Commission considered early on nearly doubling the monumental core not counting East and West Potomac Parks created when the Potomac River was dredged during the 1880s. On 15 April Burnham wrote Olmsted: "my own belief is that instead of arranging for less, we should plan for rather more extensive treatment than we are likely to find in any other way. Washington is likely to grow very rapidly from this time on, and be the home of all the wealthy people of the United States." [27] At the 19 March 1901 Senate subcommittee hearing, New York architect George B. Post, who had just secured the commission to design the new Department of Justice building (which was to contain the Supreme Court) on Lafayette Square spoke about the rapidly increasing number of proposed government buildings:

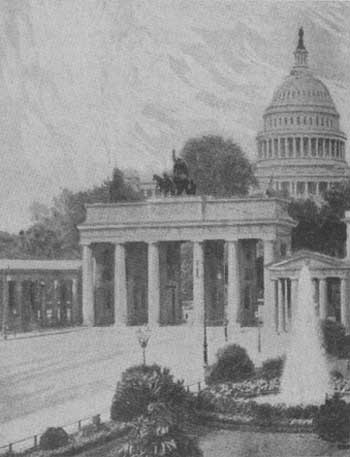

In the final report, the Park Commission decided to place the Supreme Court on square 728 on the corner of First and East Capitol streets, NE which had been suggested by Senate bill 697 in 1889. [29] Other prescient aspects of Olmsted's second figure-ground drawing include realigning the Mall to place the Washington Monument in its visual center but retaining it within its original boundaries formed by B streets North and South. Thus the south building zone became increasingly narrower and the north one increasingly wider as one moved west from the Capitol, a factor in locating large buildings such as the Agriculture Department which was considered for both sides of the Mall. The Mall's central and cross vistas were still colored tan or yellow to indicate graveled boulevards. Buildings located in park-like settings were shown lining the Mall's edges and were separated from the central vista by groves of trees. The location of the B&P railroad station south of the Mall at the convergence of Virginia and Maryland avenues remained as shown on the 27 April plan. The major change on Olmsted's second figure-ground drawing was the introduction of important water features south and west of the Washington Monument. Two proposed large rectangular pools terminating in semicircular ends were each one-third the length of the public grounds on its respective eastern or northern sides of the Washington Monument. They would have replaced the Fisheries Commission's spawning ponds located between the White Lot and the Washington Monument as well as the irregularly shaped Tidal Basin, designed by Army engineers to flush our the Washington Channel, its inlet on the Potomac River and its outlet at the head of the new channel. The Senate Park Commission's productive May meeting is recorded in the third preliminary drawing dated 3 June 1901 (pl. VI). Having earlier focused on the Mall, they turned their attention to central Washington's greater landscape, not only the new parkland resulting from the Potomac's dredging during the 1880s, but to a vast kite-shaped polygon encompassing triangles of land south of Pennsylvania and New York avenues, NW, and north of Maryland Avenue, SW. Thus, within two months of their formation, the Senate Park Commission had conceptualized the visionary extent of their project and all of its salient features. In 1929, Moore noted in his Washington Past and Present that "by June a tentative plan had been sketched. As a magnet placed under a sheet of paper covered with a mass of unrelated iron filings brings the particles into symmetry and beauty, so under these organizing minds in close consultation the disordered elements in the District of Columbia fell into their proper relations one with another." [30] Because the final report discussed each section within this kite as a "division," it is convenient to trace the plan's evolution from June 1901 through January 1902 section by section. Treatment of the Capitol and White House divisions, each framed by appropriate legislative and executive department buildings, was not settled until very late in the commissioners' design process. Therefore, base brownline drawings used beginning in June include only the Capitol and White House grounds and not the squares that surround them. The Park Commission's report divided the east-west Capitol axis into three divisions, the "Mall," "Monument Section," and "Lincoln Division" crossed on the north-south axis by the "White House Division," "Monument Section," and "Washington Common." The Mall Triangle was the only one of the four triangles that abutted this central Latin cross to be dedicated to buildings, the other areas being laid out as parks. [31]

Post's March 1901 suggestion to group future executive buildings near the White House responded to Supervising Architect James Knox Taylor's January 1900 scheme to locate them on the residential blocks that flanked Lafayette Square. In 1901, the future of James Hoban's President's House, whether it would remain as the President's home, official residence, and office, or be enlarged, or become solely the President's office, had been debated for the previous decade. Large public events and general public access to the White House had subjected the building's structure to strains that were not foreseen when it was erected in the 1790s. In 1902, McKim's firm was hired to restore the White House (its interiors dating from several Victorian redecorations) to its original appearance and to design a temporary office building on its west side. On Monday, 27 January 1902 Burnham met with Roosevelt about the new executive offices and Moore recorded in his diary that "he [Burnham or Roosevelt, it is not clear who] favored [the] site of St. Johns Church and John Hay's house," thus conforming to the commission's just completed plan. By 14 April Burnham was advocating locating the "permanent quarters for the President" in the center of Lafayette Park. The second edition of the Senate Park Commission plan did place a building in the square's center. [32] The legislative and executive groups were not added to the Senate Park Commission's drawings until mid-December 1901. In the interim, the commissioners considered many alternate solutions. On 30 July 1901 soon after returning from Europe, Burnham suggested "that we place the President's House on the site of the old (Naval) Observatory" on a high bluff overlooking the Potomac River between 23rd and 25th streets, NW. After a day at Oxford, Burnham recorded in his diary that the travelers "reached hotel at 11:30 and talked an hour or more about the President's House and grounds;" erecting a new building at 23rd Street was still under consideration at the end of October when Olmsted noted that if it were to happen, the Heurich brewery would have to be removed. This is the third instance where the commission took advantage of elevated positions within the city to create terraced overlooks, apparently an effect that deeply impressed them all during their European trip. The Washington Monument terrace was their most developed and imposing design, but in December 1901, the commission began planning more prominent terraces for the Capitol's west front to extend those erected in the 1880s, designed by Frederick Law Olmsted, Sr., adding a lower terrace enclosing a pool connected to Olmsted's terrace by a second pool (fig. 4). [33]

In the late nineteenth century the area between the Mall and Pennsylvania Avenue was partly industrial, partly commercial, and partly working-class residential. Its character was a serious impediment to both the development of the Mall as a gracious public space and Pennsylvania Avenue as a world-class boulevard. "A well-known architect of the city," possibly Paul Pelz (architect of the Library of Congress), noted in the 17 April 1886 Washington Evening Star that Pennsylvania "avenue should be made a grand driveway, and the government ought to buy the squares at the south of the avenue, and bring the reservation, or park, up to the south side. Then that would allow plenty of space for the public buildings, which will be erected, and, at the same time, beautify one of the grandest driveways in the world." [34] The sad state of America's main street—and its possible greatness—was Frank Sewell's recurrent theme in 1892 Evening Star articles. "Undoubtedly Pennsylvania Avenue, of which the American loves to boast, is, as a roadway, one of the finest in the world, while, as the great central promenade and public thoroughfare of a capital city, it is probably, in its architectural display, the meanest and most insignificant." Sewell advocated the "proper utilization of the avenue for the government and district buildings under a consistent and imposing architectural plan." He noted further that "it is probably not far from the truth to say that had the War, State and Navy, the Interior, the Pension office and Post office and Treasury been built with a single front, instead of in quadrangles, and located on the south side of the avenue, they would have formed a continuous line of palaces extending from the White House to the Capitol." If a national art commission were formed to regulate a coherent and unified design for buildings recently proposed by federal agencies or private groups, Sewell contended, "we might look hopefully forward to seeing not many years hence the avenue graced on either side with beautiful colonnades and arcades lining the front of our new District buildings—public library, museums, auditor's offices, Indian Department, geological survey and musical and art conservatories, and possibly the government's own national university." [35] An undated article from the New York Evening Post, filed with papers dating from March 1901, noted:

Thus the Park Commission did not originate the idea of developing the Mall-Pennsylvania Avenue triangle as a campus of public buildings, but it did determine where each individual building should be located within the triangle and their spatial and formal interrelationships. On 21 December 1901 when they were putting the finishing touches on the drawings, McKim wrote that an unspecified building facing Pennsylvania Avenue "adjoining the proposed Armory, was not made parallel to Pennsylvania Avenue, because it faces a Public Square. But for the invasion of the Square, it would have been made parallel with Pennsylvania Avenue. The site of the proposed new Municipal Building is a similar one. There is no doubt that the architecture of the South side of Pennsylvania Avenue should, as far as practicable, be made parallel with the Avenue." [37] By the spring of 1904, in preparation for legislative action to acquire the land in the Mall triangle, Nevada Senator Francis Newlands (one of the Park Commission's staunchest supporters), proposed changes. "His idea," Washington architect J.R. Marshall reported to McKim, "is to obliterate all minor streets in it, and keep only the necessary thoroughfares. He proposes, for instance, to reserve the section north of the New Museum [Hornblower and Marshall's design] from B street to Pennsylvania Avenue for the growth of the Museum." Newlands advocated similar room for expansion of the Agriculture Department (should it be located on the Mall's north side) and other changes to the Senate Park Commission's plan, including "moving back the building line on the south side of [Pennsylvania] Avenue and planting trees, and making a bridle path under them." [38] McKim was particularly cognizant that the proposed new buildings in the triangle and on the Mall must have the same kind of definition on the model of the Senate Park Commission's plan as was shown on its drawings prepared for exhibition in order to be convincing. On 15 January 1902 this model went on display at the Corcoran Gallery in an unfinished state; McKim wrote Moore that day:

Once the commission had organized the Mall's length into nine east-west zones (two walkways framing the central space were added to the former seven zones) and determined its axial orientation, the basic issues they addressed were the width of each zone, the relationship of the buildings in the outer zone to their sites, the length of each segment as defined by cross streets, the Mall's grade, and its special features. The 1792 engraved plans of Washington described the Mall's center open space as being 400 feet wide out of a total width of 1,600 feet, with 1,000 feet between façade lines. In March 1904, when building lines for the Department of Agriculture and the National Museum were being debated in the Mall Parkway hearings, Olmsted recalled the problems the commission faced in determining the widths of the Mall's various zones:

Burnham testified during the Mall Parkway Hearing that having designed the central parkway, its width became the burning question:

In his 1929 biography of McKim, Moore related that "McKim determined that the width of the grass carpet between the trees at Hatfield House should serve for the space at the Mall. The grouping of four trees on the Mall was suggested by the six rows on either side of a central grass plot at Bushy Park." The experience of visiting English parks in July 1901, may well have confirmed visually the monumental spatial effects created by long plantations of trees, but the commissioners had depended on their visits to American colonial sites, maps of European parks, and their careful study of L'Enfant's plan to determine this aspect of the Mall's character before they embarked for Europe. In his 1904 congressional testimony, Burnham related the Senate Park Commission's experiment of erecting flag poles on the Mall 250 feet, 300 feet, and 400 feet from its center line to determine proportionally the best width; in late May Langdon and Moore worked through the Supervising Architect's office to arrange this demonstration to coincide with the commissioners' next meeting in mid-June. Two dated preliminary plans made by the Senate Park Commission in late April and early June help clarify the sequence of influences. [42] Langdon's second 27 April 1901 drawing, made subsequent to the Senate Park Commission's first formal meeting, showed the Mall's central space lined with five rows of trees with an inscription in the margin indicating that the groves were 225 feet wide, the rows 45 feet apart (see pl. V). The Senate Park Commission's report noted that plantations of rows of elms were common in many European gardens, "in those towns, North and South, which were laid out during the colonial era," and even the Mall in Central Park. [43] Burnham's 1904 congressional testimony gives both valuable insights about the Park Commission's aesthetic intentions and clarifies the historical record:

The Senate Park Commission's preliminary plan dated 3 June (drawn on the same base map as their 27 April design) had wider plantations of trees than the 27 April design, but the number of rows and their planting widths were not specified. Narrow promenades, however, ran down the centers of these groves as described by Burnham in 1904. Although Burnham's 1904 testimony subtly suggests that this lesson was learned while the designers were in Europe, the decision about the general width of the Mall's zones was made before the event. Certainly avenues of trees are fundamental to European landscape architecture and were the source of the commission's thinking, but the trip to Europe only verified this aspect of their design, apparently determined during their second meeting in mid-May 1901. The issue was so important that it was an ongoing discussion; McKim noted at the Mall Parkway Hearing that the distance between building facçades on L'Enfant's Mall had been 1,000 feet:

Moore later quoted Burnham speaking on 6 June: "I have talked the matter over with Senator McMillan. The four of us are going to Europe in June to see and to discuss together parks in their relations to public buildings—that is our problem in Washington and we must have weeks when we are thinking of nothing else." Plans of square, rectangular, and quadrangular buildings sketched in the outer zones on the 3 June plan nearly filled each block. Footprints of buildings on plans among McKim's papers made after the European trip—unfortunately too light to reproduce—modified the size, shape, and number of the Mall's projected buildings. Their number gradually increased as they were reconfigured in response to projections about the country's growth and the government's future space needs. These numbers took into account the future executive buildings planned to encircle Lafayette Square, legislative ones framing the Capitol Grounds, and a miscellany of buildings projected for the Mall Triangle. Although the sum total of the Senate Park Commission plan was visionary, each of its parts responded to specific mandates rooted in actual needs. [46] On 23 August 1901 McKim sent Supervising Architect of the Treasury James Knox Taylor, the government's advisor on the Department of Agriculture building, specific widths of streets, curbs, sidewalks, and setbacks:

Olmsted probably solved the problem of realigning the Mall without having the building zones become progressively narrower or wider. He off-set B Street South in the 500 block where it converged with Maryland Avenue and B Street North at 7th Street on the edge of the marker-station cross axis, effectively masking the shift from the Mall's east and west ends (see pl. V). On both the 3 June and 30 August drawings the building zone blocks are the same width their entire lengths; the disparity between their respective widths would hardly be noticeable because they were separated by the two groves of trees and the central space, a total of 890 feet. By 3 June the central boulevard had been changed to a parkway flanked by graveled avenues; the 30 August drawing (fig. 5) is not color coded but we know that the central lawn treatment was retained in the final design. In his biography of McKim, Moore suggested that the greensward was a result of the European trip: "Windsor Great Park, with its central driveway, emphasized Olmsted's objection to running a road through the center of the Mall," but the decision had been recorded on a drawing dated two weeks before they embarked. [48]

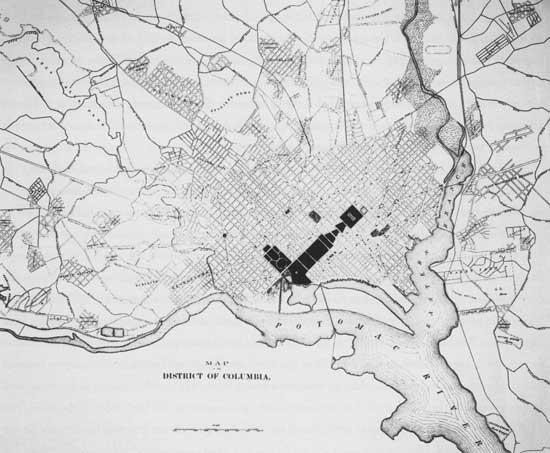

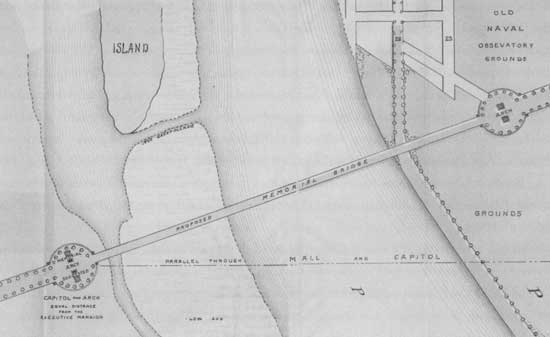

In proposing its visionary plan, the Senate Park Commission supposed that the historical jurisdictions over the Mall's reservations would to be negated by some future law. In 1901 the Smithsonian Grounds ran from 7th to 12th streets and the Department of Agriculture had jurisdiction between 12th and 14th streets with the 1400 block considered part of the Washington Monument grounds. By 3 June the commission had regularized the Mall's blocks in relation to the city's cross streets, with three blocks east of the marker-station cross axis and three blocks west of it. The two easternmost blocks were to be the same length, while the one between 6th and 7th streets was slightly shorter; the circular pool at the head of the mall was surrounded by a circular plaza, the whole enclosed by trees. West of the market-station cross axis, the Park Commission initially created two long blocks of equal length followed by a short one by running streets across the Mall at 9th, 11th, 14th and 15th streets. By 30 August, however, the designers had divided the two long blocks by inserting three circular elements, possibly fountains or possibly sculpture, in the center of the parkway and amidst the trees. The plan of the Mall included in the Senate Park Commission report (pl. VII) published in the spring of 1902, divides the area west of the cross axis as in late August. The accent elements within the tree line have been deleted but those on the Mall's center line were retained. Both cross streets or vistas between buildings caused breaks in the groves of trees; Park Commission members repeatedly invoked L'Enfant's plan as their source for complementary vistas between buildings. In the end the Park Commission determined that "museums and other buildings containing collections in which the public generally is interested" should be located on the Mall's north side, while those on the south should be dedicated to "buildings in which the scientific and technical work of the Government is done." [49] The question of how to orient the new Mall buildings in relation to the existing streets was posed by Washington architects Hornblower and Marshall in April and May 1904. Initially the commission suggested that buildings be erected out of square so that their north and south facçades would be parallel to either B Street North or South as well as to the Mall's adjusted axis. Hornblower and Marshall argued that the square figure 8 configuration of their National Museum—5 19 feet long and 375 feet deep—could not be skewed so the decision was made to conform to the Mall's axis and place the museum at an angle within its square. [50] Regularizing the Mall's grades was one of the commission's earliest concerns but the first textual evidence of the "continuous platform," or terrace, along the Mall's north side is in a letter Olmsted sent McKim on 31 October 1902. Olmsted suggested that a terrace along B Street North, beginning at 6th Street gradually rise to 34 feet in height at 14th Street (and possibly higher in the next block) to form a platform into which the new buildings would be set "forming an extension of the basements of the buildings." Hornblower and Marshall set the basement of the National Museum in a partially sunken well on the Mall side but fully exposed it on the street side to accommodate the circa 17-foot height difference (fig. 6). In early February 1905, civil engineer Bernard R. Green, employed by the Corps of Engineers to oversee construction of the museum, noted that "where the present cross slope is greatest it is only about 25' in the whole width. Even between the 890 ft. lines, that much cross slope would seem hardly to be noticeable on the ground and amongst the trees." McKim's telegraphed reply was to ask Green to raise the museum's first floor from 24 feet to 25 feet above the street, this small change in McKim's judgment "would essentially appreciate value of base line Capitol to monument." Green worked with Hornblower & Marshall to raise the museum an additional three feet, partly to get a better north entrance, better drainage, better light, and "to get a greater height of cornice and sky line," which satisfied McKim. McKim had been instrumental in persuading the Agriculture Department to lower its grade "so that the whole composition may have reference to the dome and the needle," making both buildings properly subordinate to the Mall's two defining elements. The base line of the Capitol's west façade at 90 feet was McKim's major reference point in determining the Mall's grading. [51]

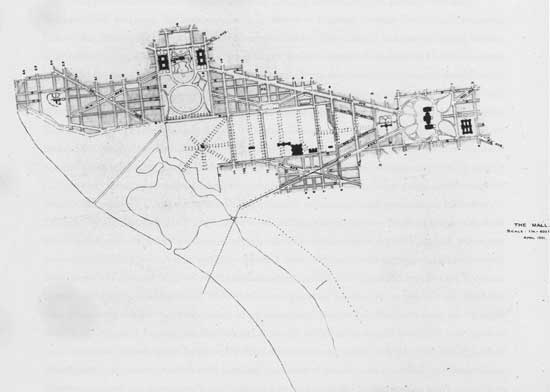

Olmsted does not mention in his October 1902 letter to McKim how the terrace was to be contained where it abutted North B Street. During the Mall Parkway hearings in 1904 Burnham was questioned about this issue. He calculated that 160,000 cubic yards of fill would be necessary "to build up to the grading line," adding $48,000 to the cost of reclaiming the Mall. "I will add to that a wall, which would perhaps be $30,000." A retaining wall along the Mall's north edge would not require placing the streets crossing the Mall in a viaduct, in Burnham's opinion. Rather, "streets would cross the Mall by a depressed grade, which would be a thing of great beauty, as everyone sees who rides along the Capitol grounds where such a grade exists. You look down, the hill falling away from you. It is a thing of great beauty, and so it would be with the streets coming from the Mall." Frederick Law Olmsted, Sr., had designed these carriageways in the Capitol grounds during the 1880s. [52] Olmsted's and McKim's manipulation of the Mall's landscape achieved simultaneous pragmatic and aesthetic goals. Olmsted's 29 October 1902 drawing (fig. 7) acknowledged that razing the Smithsonian and other Victorian buildings on the Mall's south side was not likely in the near future. Groves of trees between 9th and 12th streets are shown abutting the Smithsonian Institution, planted on a terrace three feet higher than the Mall's center line (a graduated terrace now makes the transition). Moreover, the green walls created by these groves would effectively mask the building's then-despised architecture. Although it was not the subject of correspondence (which focused on the cross Mall grades), McKim planned forced perspectives for the Mall (and later for West Potomac Park.) The Mall's actual length of nearly a mile and a half would be visually lessened by creating an extended bowl, the Capitol grounds terracing down from its 90 foot elevation and the Mall gradually rising to the Washington Monument's 40 foot elevation. Both would appear closer than they actually were to visitors within the central greensward, the "tunnel" of trees giving them even greater prominence.

About 18 November 1901 McKim sent Moore a pencil sketch plan (fig. 8) of the terrace with alternate designs of how to extend the Mall's plane up to the monument's base. He was considering whether to break the Mall's rows of elms at 15th Street or to tunnel the street under the Mall rather than interrupt the grand approach to the Washington Monument. The commission's final report recorded McKim's decision: "The bordering columns of elms march to the Monument grounds, climb the slope, and spreading themselves left and right on extended terraces, form a great body of green strengthening the broad platform from which the obelisk rises in majestic serenity" (p. 47). In 1899, classical scholar William H. Goodyear remarked that McKim, Mead & White were the first modern architects to use "the Greek horizontal curves on an extended scale" in their work at Columbia University. McKim applied the same principle to the Mall and West Potomac Park to create these forced perspectives. [53]

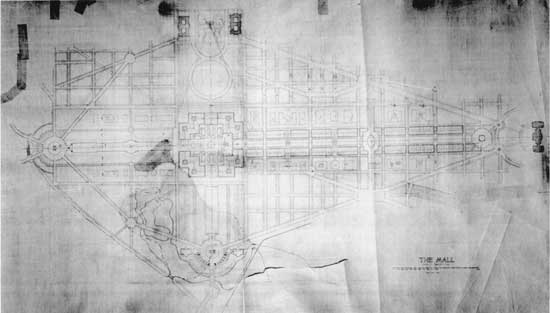

By 3 June 1901 the Senate Park Commission had developed the market-station axis into a major Mall element specifically to heighten the experience of those arriving at or leaving from the B&P station. Its center contained five pieces of sculpture out of eleven works planned for the Mall at this time. Two days earlier, McKim wrote Burnham about the value of adding sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens to the design team, citing the contributions he had already made:

Saint-Gaudens was added to the Senate Park Commission, but because of illness he did not join the other members on their European trip when they made substantial changes in the location and nature of the plan's sculpture. In mid-November, McKim reiterated Saint-Gaudens role: "upon his judgment will largely depend the selection of sites, for such monuments as the Lincoln, Grant, Garfield, McKinley, Sherman, Sheridan and McClellan, and the solution of other problems not less essential to the work of the Commission." By 30 August, the sculpture garden initially planned for the Mall cross-axis had been replaced by groves of trees. The designers initially envisaged hansoms entering or leaving the station's forecourt on 7th or 9th streets, a grand vehicular entrance into the city. Visitors would have passed by the monumental sculpture garden in the Mall's center with fleeting glimpses of the Washington Monument and Capitol in the distance. When the railroad station was no longer part of the Mall's equation, the sculpture garden lost its function as a place to be experienced from a moving vehicle and was replaced by parterres to be enjoyed by pedestrians. The commissioners then suggested that a new District government building replace the Center Market at the north end of this intermediary cross axis and the new National Museum occupy its south end; both buildings would be visited by large numbers of pedestrians. [55] After Union Station was officially relocated to Massachusetts Avenue north of the Capitol at a meeting between McMillan, Cassatt, and Burnham on 3 December 1901, Burnham continued to conceive of the station as a vital element in the commission's plan. He wrote McKim ten days later:

Burnham's sketch of the Union Station design (fig. 9) published in the Park Commission's report was for the site of the B&O station on New Jersey Avenue, NW, adjacent to the Capitol grounds which he preferred to Massachusetts Avenue NE. He wrote Olmsted: "You probably will change your mind about the beauty of the location when certain considerations are placed before you which McKim and I considered last Sunday....I have a scheme for making a deep fore-court of the terrace wall between the court and the Capitol grounds, which will subordinate the depot and give it its proper artistic relation to the Capitol." Burnham planned a sunken court with two sets of staircases flanking a monumental fountain leading to a terrace at the station's entrance level, one of several echoes of Vaux-le-Vicomte in the commission's work. Once the Massachusetts Avenue NE site was chosen, Burnham designed a semicircular plaza with "three fountains whose locations at the three focal points would place a glistening dome of water in the vista of all the principal streets approaching the plaza, constituting an effect of exceeding beauty." In 1907, Burnham suggested that a monument to Christopher Columbus be erected in the plaza and he later collaborated with Lorado Taft in the design of the Columbus Fountain, erected in 1912. [57]

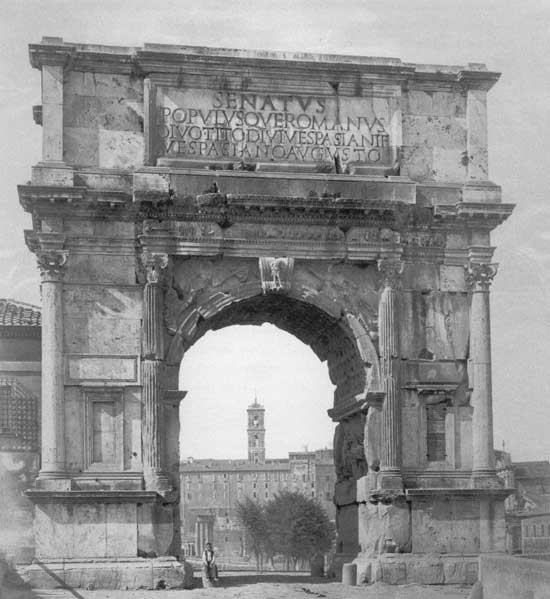

In 1903 and 1904 Olmsted critiqued Burnham's site plans for Union Station, suggesting proper angles of streets radiating from this plaza in order to get the best vistas. At the time the Park Commissions report was published, Burnham had conceived of the station's façade based on the Arch of Constantine (fig. 10) as "equally as dignified as that of the public buildings themselves." He felt strongly that although it was located just outside the boundaries of the new plan, "this station is intended to be monumental in every respect and to be in keeping with the dignity of the chief city of America and with its present and future beauty." Only the station's outline plan and that of a large semicircular plaza appeared on the main Senate Park Commission plan (see pl. VII), probably because Burnham's firm had not completed its design in time to be included. [58]

During its May 1901 meeting the Senate Park Commission determined that the best solution to the Washington Monument's placement 371.6 feet east of the White House axis was to create a positive feature from a negative circumstance. Their 3 June preliminary design replaced the utilitarian Fish Commission's hatcheries north of the monument and greenhouses to its south with a vast public garden comparable in size to the White Lot south of the White House (see pl. VI). Spanning the Mall and the White Lot widths, this square was subdivided into fourteen square units to create a Greek cross at the center of the great Latin cross that regulated the monumental core's overall design. The corner squares were colored deep green on the 3 June plan indicating that they were to be planted with groves of trees. Eight wide boulevards traversing the Monument Gardens connected the Mall's carriageways with those in West Potomac Park and those in the White Lot with drives in the new park south of the monument. After McKim showed Saint-Gaudens this design, the sculptor wrote Burnham that he "thought it so splendid and was so impressed that I want at once to tell you how it struck me. Great Caesar's chariot ought to go through and if my shoulder would be any good at the wheel let me know and I'll push till I'm blind." Until their European trip, the commissioners conceived of the Mall as the center of a vast nexus of carriageways from which one enjoyed the city and explored the surrounding countryside. In 1904 it was estimated that the Park Commission plan gave Washington 8,000 acres of parkland connected by 65 miles of carriage or parkways. [59] The crossing of the central axes was a series of three concentric squares, possibly a stepped pyramid formed by extending westward and geometrizing and leveling the roughly conical mound on which the Washington Monument stood. A monumental piece of sculpture stood in the center of the inner square, its plaza approached by diagonal pathways leading through the turfed middle square. Four additional sculptural works were located at the corners of the forested outer squares. For the Monument Gardens, McKim applied the same design principles used by his firm for the plan of Low Library and its plaza (1892-1898) at Columbia University. The three-dimensional richness of this campus setting, achieved through terracing and diagonal circulation, resulted in Columbia's premier gathering place and provided multiple connections to adjacent buildings. At Monument Gardens, McKim also introduced the third dimension of graduated height to change the simple geometric forms into a powerful planning device. André Le Nôre's parterres flanking the central vista at Versailles, each laid out as a Greek cross within a square traversed by diagonals, provided the basic geometry for the plans of both Low Library and Monument Gardens. But the idea of overlooks was McKim's valuable design contribution, in the case of Washington, the monument's already elevated position suggesting such a treatment. [60] After the Mall's character changed during the European trip from a vast system of lengthy carriage drives to a series of specific park experiences, the Monument Gardens was transformed into a pedestrian enclave laid out on a plane "as extensive as the piazza in front of St. Peter's in Rome." Its geometries laid down on the 30 August drawing had become more complex, two superimposed Greek crosses, each subdivided by pools, parterres, groves of trees, or sites for sculpture. The inner Greek cross was framed by four W-shaped corners densely planted with trees, each containing two circular open spaces for small monuments, their zigzag shapes leaving the four corners as open lawns, a figure-ground reversal from the 3 June design. All four of these W-shaped groves of elm trees were planted on 40-foot high terraces, their inner walls framing an elaborate sunken garden. [61] On 30 August 1901 Burnham wrote McKim a long critique of four alternate schemes for Monument Gardens McKim had sent him:

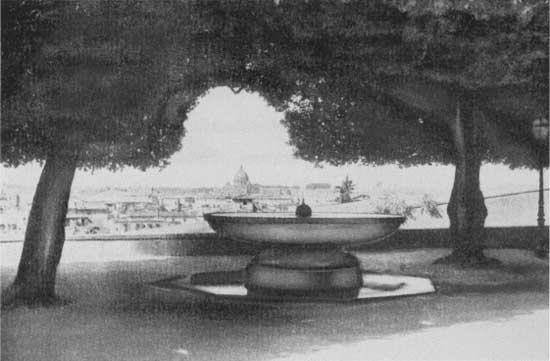

McKim anticipated Burnham's advice as scheme "A" was recorded on the drawing dated 30 August 1901. The function of the terraces in the Monument Gardens was the emphasis in the Senate Park Commission Report, which considered that the "groves on the terraces become places of rest, from which one gets wide views of the busy city." Paths within the elm groves led to squares containing fountains to the west and classical temples to the east of the obelisk. The report's photograph 175 (fig. 11), a panorama of Rome from the terrace of the Villa Medici, illustrated the "public value of hilltops wisely treated": the dome of St. Peter's in the center is seen framed by trees clipped to enhance the view. The experience of this and other urban terraces during their European trip were particularly noted by the Senate Park Commission because the White House, Capitol, Washington Monument, and buildings on the Mall's south side were already located on elevated grounds. McKim's goal was to take greater advantage of Washington's vast natural panorama and picturesque setting by either creating or reinforcing a series of overlooks from the Capitol to the Potomac River. [63]

The Senate Park Commission also planned vistas towards the city, described by Burnham in his draft of the final report:

McKim suggested that Moore revise the text of his comparison of Washington with European capitals for his Century Magazine articles to emphasize its topographical advantages and delete references to all "Royal country seats." He said, "When one recalls the setting of many foreign Capitals and their flat topography, one realizes that with so superb a beginning, and with the majestic Monument in a vista closed by the Potomac and the Virginia Hills, the possibilities for beautiful treatment of Washington are unequalled." He went on to caution about using too many superlatives. "I suggest, as more conservative and in line with the excellent tone and restraint of your article, that the preeminence of the Capital, above other cities in the world, as the most beautiful, be avoided, and that the sentence be made to read so that the Capital should stand as one of the most beautiful cities of the world? If this could be made true would it not be fine enough?" [65] "The Washington Monument Division" in the 1902 report includes eleven drawings and a photograph of the model showing views to, from, and within the monument gardens (pl. IX). The designers acknowledged that "no portion of the task set before the Commission has required more study and extended consideration than has the solution of the problem of devising an appropriate setting for the Monument." Further, they believed that their design was the "best adapted to enhance the value of the Monument itself." When Olmsted reported on the history, design, and status of the Senate Park Commission's plan to the AIA convention on 11 December 1902 he explained the intended effect of the sunken court. "The actual intersection of the axes cannot be marked by any object which could be brought into comparison with the supreme shaft of the Monument, so it is proposed to mark it by a void—a great circular water basin set in a sunken garden, flanked and enclosed by terraces. At the head of the great bank of steps, 300 feet in width, which rise on the east from this garden like a great plinth would stand the Monument, related in position to the crossing of the axes like the altar at the crossing of a church." Burnham's critique of McKim's design of the Washington Monument Gardens reinforced these sacred associations. "The Court is a shrine, to which one should climb, constantly going up....Are not these open spaces that enclose the Grand Court the Court's real vestibule; and is not the Court itself the real inner vestibule to the stairway that leads up to the monument itself, which is the principle of the whole composition." Saint-Gaudens apparently suggested that Robert Mills's original intention of using the shaft's base for inscriptions be revived by "becoming a monumental 'affiche,' and that the Farewell Address, for example, should be incised upon the shaft." [66] McKim turned to Vaux-le-Vicomte's terrace wall articulated by fountains (pl. XII) set in niches as the model for Monument Gardens east side (fig. 12). On its center axis at the top of a hill overlooking the French formal garden stood a statue of Hercules, from the 1780s suggested as an appropriate symbol for America, a suggestion first made in France. Washington was seen as the American Hercules whose great strength defeated monsters and tyrants that menaced the state. Although the only textual reference to Vaux-le-Vicomte in the Senate Park Commission report was that its "cascades, canals, and fountains us[e] one-twelfth of the daily water-supply of the District of Columbia," many photographs of its water features were taken by Olmsted during the commission's visit. Moore's biography of McKim, however, emphasized Vaux's iconography and its impact on the visitors, albeit nearly three decades later:

Although Moore may have telescoped travel reminiscences and remembered conversations, there were three visual references to Vaux's fountain wall in the final plan, at both ends of the West Potomac Park canal and in the forecourt of Union Station. Moore's diary entry for 15 January 1902, the day when the exhibit of models and drawings opened, was unusually lengthy: "Went to Corcoran Gallery with Senator McM and Gallinger to meet President. When he saw me he came through the knot of people and thrust out his hand in the old way. He fell foul of the small model of Monument, saying it looked like fussy work. I expostulated but he insisted until Mr. McMillan took him to see the pictures of the Monument. Then he frankly acknowledged his error and took back all he said." Moore felt that artistry reached its highest point in McKim's Monument Gardens design. [68]

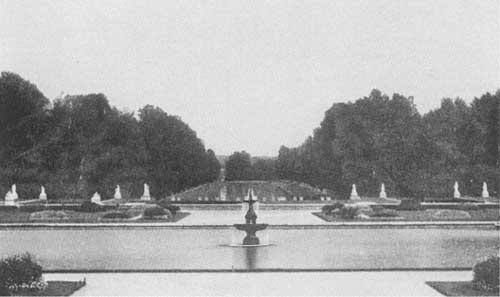

After the Senate Park Commission expanded the Mall to form a great kite during their May 1901, meeting, vehicular drives throughout the expanded area were fundamental to their thinking. Five miles of carriageways had wound through A.J. Downing's picturesque Mall and the literature concerning Washington's post-Civil War society frequently cited both horseback and carriage rides in and around Washington as major forms of recreation. Although selecting sites for future public buildings was part of the Senate Park Commission's mandate, the development of a comprehensive park system was McMillan's major goal and the commission's primary charge. When the commissioners changed the east Mall's central axis from a boulevard into a turfed parkway in May-June 1901, they concurrently developed West Potomac Park as a series of parallel boulevards. These connected to drives around the kite's perimeter, roads flanking the east Mall's greensward, and the central boulevard west of the monument, in total at least tripling central Washington's carriage and pathways, most adjacent to or through newly proposed parklands. [69] The 3 June 1901 drawing (see pl. VI) shows building zones on the edges of West Potomac Park facing these wide boulevards, while parterres and pools flanked the central vista. While in Europe the commissioners decided on a long, wide canal framed by walkways and double rows of trees for the center of West Potomac Park. Irregular in shape—its eastern and western ends were widened slightly—the canal's great length was broken on the 19th Street axis by a circular pool. By 30 August the boulevards were narrower because they no longer passed through the redesigned Monument Gardens to connect to the Mall's drives (see fig. 6). Also by 30 August the western edge of the memorial circle had developed into a wide plaza with two roadways leading from it, one to a Potomac River bridge and the second leading to Rock Creek. Between these roadways directly behind the monument a stair, or watergate, descended into the Potomac River. By January 1902, West Potomac Park's building zones had disappeared and all internal references to Washington's street pattern eliminated and replaced by a vast parkland criss-crossed by multiple carriageways. The canal was widened slightly, its form changed to a Latin cross. In this final design, the canal's east end was terminated by an apsidal ended cross canal separated from the main canal by a narrow plaza, the germ of the future Rainbow Pool. Many of the illustrations in the Senate Park Commission Report show variations in details for many sections of their plan. These drawings were done throughout the fall of 1901 while major and minor elements of the design were still in flux. Moreover, there are many indications that the commission's overall design philosophy was to establish basic principles and a broad framework, not dictate individual elements. Commonalities among the commission's design sources reinforce a recurring theme throughout the previous century: America was the inheritor of varied European cultural traditions imported with its pan-European population. The caption of photograph 100 (fig. 13) in the 1902 report reads: "Basin and Great Canal, Fontainebleau, Suggestive of the Treatment of the Canals West of the Monument," yet the text notes that these canals were "similar in character and general treatment to the canals at Versailles and Fontainebleau, in France, and at Hampton Court, in England." [70]

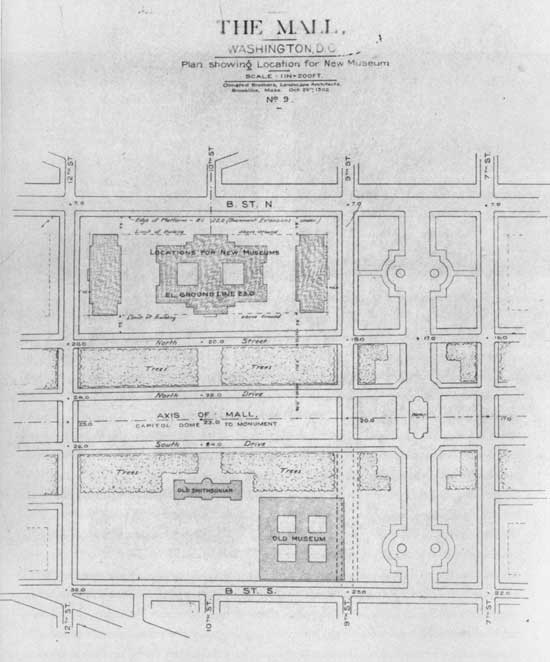

In mid February 1901, Congress had appropriated an unprecedented $250,000 to erect a Grant Memorial in Washington, specifying that it be sculptural in nature. At the initial meeting of the Grant Memorial Commission on 6 March a site south of the State War & Navy Building was selected but twelve days later Secretary of War Root suggested that the north side of the White Lot was a better location; both sites were included in the 10 April circular soliciting designs. On 7 June Root convinced the Grant Memorial Commission to delay deciding on a site until all designs had been received, not due until 1 April 1902. Root had just asked the Senate Park Commission to serve as official advisors to the Grant Memorial Commission and he wished to leave its members some latitude concerning important monument sites. [71] In May-June 1901, the commissioners decided to terminate the Mall's west axis with a vast triumphal arch on a scale comparable to Paris's Arc de Triomphe (almost 50 meters high and 45 meters wide) (fig. 14). On 7 June McKim invited Saint-Gaudens to attend the commission meeting on the 11th, "as the skeleton of the general scheme for the Mall will be discussed, and if possible accepted as the basis for future development. It is of the utmost importance the question of the establishment of permanent sites for the Lincoln and Grant especially should be reached at this meeting, and to do this effectively your presence and authority are most needful." For its siting, McKim looked back to 1894 when his firm in partnership with Olmsted, Sr.'s, redesigned Brooklyn's Grand Army Plaza at the entrance to Prospect Park to reinforce the meaning of John H. Duncan's Soldiers' and Sailors' Memorial Arch as a "national Valhalla for the Civil War." Duncan's arch, based on Rome's Arch of Titus, was located at one end of its plaza's elongated oval to collect and disperse traffic from twelve boulevards. Nine roadways converged on the arch McKim planned for West Potomac Park; it sat in the center of a double circle, a national Civil War memorial he surely intended would vie with Duncan's acknowledged masterpiece. [72]