|

Contents

|

The American Institute of Architects Convention of 1900: By Tony P. Wrenn EARLIER studies have discussed the American Institute of Architects' (AIA) convention in 1900 as a seminal event leading to the 1901 Senate Park Commission plan for Washington, D.C., yet none has closely studied the events and architects of the period who used the convention to lay the groundwork for the modernization of the capital city. [1] At the same time, these individuals actively organized local and national arts-related professional groups to exert pressure on Congress and the president to establish a federal arts bureau to oversee Washington's continuing development. What becomes clear as one studies the era, is that the research accomplished in the 1890s gave the Senate Park Commission, once it was formed, the data it needed to base its plan on Pierre Charles L'Enfant's 1791 plan for Washington. The ideas and concepts discussed at the 1900 AIA convention provided the basic outline and goals for the Senate Park Commission plan, and the art and architecture organizations already mobilized provided the plan, when completed, with a national support base. It is equally clear that the members of the 1901 commission came to their work with full knowledge of this existing base, for all had been involved in building it, and could therefore, in a relatively short time, produce a plan which would not just shape the next century of Washington architecture but have enormous influence on the City Beautiful Movement worldwide. The federal government was then (and has continuously been) the greatest source of funding for the design and construction of new buildings and for the maintenance of existing structures built for public, government, or military uses. Federal buildings had, since 1853, been designed and constructed by government architects in the Office of the Supervising Architect in the Treasury Department. [2] In the 1870s the AIA first sought a federal bureau or commission to secure designs from private architects, especially those who belonged to the AIA, an effort it intensified in the 1890s. [3] The role that the AIA later played in promoting the Senate Park Commission's 1901 plan for Washington was an extension of that policy of promoting the best design for America's public buildings.

Perhaps the most important factor influencing the AIA in the 1890s was the friendship forged among a group of men of divergent occupations but similar interests in the arts. At the center of this group was Washington architect Glenn Brown (1854-1932), who as a public historian, and after 1898 secretary of the AIA, supervised its local and national program (frontispiece). [4] Earlier in the decade Brown had studied L'Enfant's plan for Washington and led a crusade to revitalize the city's central core based on that plan. [5] He was especially suited for this leadership, for, as the son of a prominent Alexandria, Virginia, physician, and the grandson of a United States senator, he had been raised in a privileged world. He studied at Washington and Lee University (1871-73), where his classmates included George E. Chamberlain, who was elected to the U.S. Senate from Oregon in 1908, and James L. Slayden, who served in the House as a representative from Texas beginning in 1897. Both were important Capitol Hill contacts and supporters of Brown. Author and ambassador Thomas Nelson Page, who served as president of the Washington Fine Arts Society and as an officer of the Committee of One Hundred for the District of Columbia, two powerful local lobbying groups, was another Washington and Lee classmate of Brown's. [6] Page lent his Washington residence, designed by the New York firm McKim Mead & White, for meetings and for entertaining visitors important to the campaign to revitalize the L'Enfant plan. At the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), where Brown studied after he left Washington and Lee, William Robert Ware, the father of American architectural education, became Brown's mentor and friend. Ware later sponsored Brown for membership in the AIA, and Fellow of the American Institute of Architects (FAIA), the institute's highest membership category. One of Brown's MIT classmates was Francis Bacon, brother of Henry Bacon, the architect of the Lincoln Memorial, one crucial element of the Senate Park Commission's 1901 Mall design. [7]

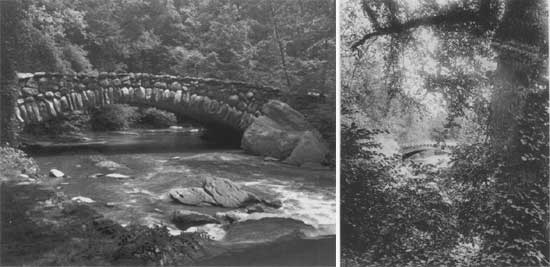

When Brown established his practice in Washington in 1880, he readily found clients, the majority of whom were in Washington's Elite List. He designed a number of buildings at the National Zoo and naturalistic bridges for Rock Creek Park during the next two decades (fig. 1). He was a finalist in several important competitions, his works were widely illustrated in the architectural press, and his reputation as an architect and designer was secure before he turned to administrative work related to public architecture and planning. [8] In 1887, Brown had been a founding member of the Washington chapter of the AIA. It would become one of the leading AIA chapters, important not just in defining the role of the professional architect, but also in organizing national support for AIA causes, including, ultimately, the Senate Park Commission plan for Washington.

One of Brown's most important contributions to Washington's architecture was his study of the U.S. Capitol. This project developed as a result of his interest in the Octagon, a distinguished early-nineteenth-century house completed in 1801 to the designs of William Thornton, whom Brown would establish as the Capitol's first architect. [9] The Capitol had additional significance for Brown. His great grandfather, Peter Lenox, had been the Capitol's superintendent of construction between 1817 and 1829, and his grandfather, Bedford Brown, had served there as a senator from North Carolina from 1829 to 1840. Portions of Brown's history of the Capitol, serialized in the American Architect and Building News in 1896 and 1897, caught the attention of Senator James McMillan of Michigan, chairman of the Senate Committee on the District of Columbia, and McMillan's aide, Charles Moore. They suggested that Brown's essays be published as a Senate document, and the first volume of his History of the United States Capitol was issued in 1900, with the second volume appearing in 1903. [10] The work established Brown as one of the most prominent historians of public architecture in America (fig. 2).

At the Cosmos Club, a private organization of Washington's intellectual elite, Brown often talked about L'Enfant and the growing movement to revitalize Washington's original plan. Architect Cass Gilbert later wrote "that it was Charles Moore and Glenn Brown, who, talking to a group of architects one evening at the Cosmos Club, urged that the architects should throw their fullest efforts in favor of the return to the L'Enfant plan, and by their earnest persistence prevailed upon those present to interest themselves in the subject." [11] Ultimately Brown's ability to manage the movement to resurrect key elements of L'Enfant's plan depended as much on his social and professional contacts as on his organizational ability. It was fortunate for the cause that Brown spoke as a successful and knowledgeable architect and historian.

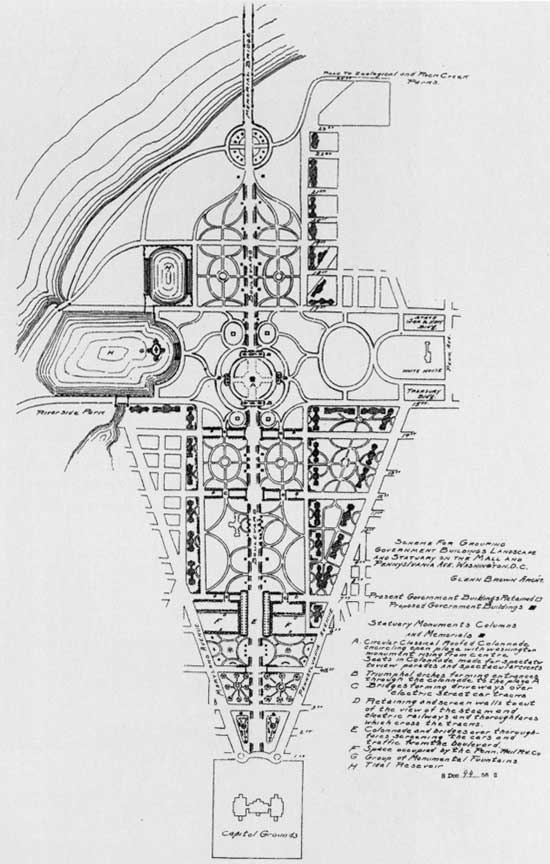

In his 1894 article "The Selection of Sites for Federal Buildings," published in Architectural Review, Brown lauded L'Enfant's placement of the Capitol and White House. "It is difficult to realize the pleasure produced by the sight of the [Capitol] building as seen from the hills of the District, Maryland, and Virginia. The Dome is constantly peeping out through the trees down the valleys in the most unexpected places as one drives or wanders through the country...." [12] Brown argued for restoration of the Mall, noting that it was feasible, but that "the probability of such wise action without a competent Bureau of Fine Arts is infinitesimal." In his autobiography, Memories, published in 1931, Brown recalled that the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition held in Chicago provided inspiration for what might happen in Washington. "A plan. . . if carried out under the direction of artists, equal to the corps employed at the World's Columbian Exposition, would give the country a parked avenue in Washington unequaled by anything in the world—a triumph of the arts" (fig. 3). Brown had visited the Chicago exposition as architect Daniel Burnham's guest and the two men worked closely together when Burnham was president of the AIA in 1894 to 1895. [13]

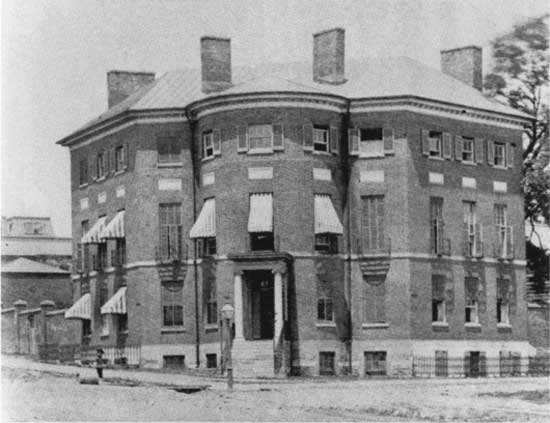

In 1895 the Washington Chapter of the AIA and the Cosmos Club organized the Public Art League, a national body with a national membership, to lobby for the fine arts. Richard Watson Gilder, editor of Century Magazine, was elected president, architect Charles Follen McKim, first vice-president, and sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens, second vice-president. Landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. and Daniel Burnham were among the directors, and Brown was corresponding secretary. He later wrote: "We found appeals to Congress by our small local body accomplished nothing. The way to the legislator's brain was through marked interest from their home voters." [14] The organization's main goal was to establish a national fine arts commission composed of the country's leading artists. In a related move, Brown and the Washington chapter of AIA argued that the headquarters of the AIA, a national organization, should be moved from New York to Washington. [15] This was accomplished in 1898, when the Octagon House was rented, and as of January 1899 became AIA national headquarters The building was purchased in 1902 and is still owned by the AIA (fig. 4). [16]

Brown was elected secretary of the AIA at its 32d convention held in Washington 1-3 November 1898. The convention proceedings for that year noted that "promptly at 2 o'clock the members, with their wives and lady friends, went in a body to the White House and were received in the East Room, each member being introduced by the Secretary of the Institute to President McKinley by whom they were cordially greeted." From the White House they went to the Treasury Department to meet Secretary of the Treasury Lyman Gage and visit the Office of Supervising Architect. A reception art the Octagon followed where they viewed an exhibition of architectural drawings and inspected the house, then being prepared to serve as AIA headquarters. A special feature of the exhibition was "many of the original drawings of the Capitol, which had been found, after diligent research by Mr. Glenn Brown." [17] In accordance with newly adopted organizational policies, Brown's position as the AIA's secretary, beginning in 1898, combined most of the duties of the modern Chief Executive Officer, Chief Operating Officer, and Chief Financial Officer. At the same time, a term limit of two years was set for AIA presidents, effectively reducing their power. [18] During Brown's tenure as secretary (1898-1913), nine AIA annual conventions were held in Washington. Brown was able to offer visiting dignitaries and distinguished architects special privileges, including guided tours of the White House "through the basement, then through the principal floor . . . ending up by taking them out on the south portico and calling their attention to the beauty of the grounds and to the charming view of the Potomac." [19] It proved most useful in the decade after 1898 to have the AIA, the Washington chapter of the AIA, and the Washington Architectural Club under one roof in the Octagon. These three would soon be joined there in the decade after 1898 by the Archaeological Society of America, the American Academy in Rome, the American Federation of Arts, the National Society of Fine Arts, and The Washington Society of Fine Arts. This last organization had been founded by members of the Washington chapter of the AIA, and its 1914 yearbook noted that the group had "lent its aid in developing Washington into the most beautiful city in America, if not the world, strongly advocating the adoption of the Park Commission Plan." [20] Though other organizations were involved, these constituted the core that orchestrated a national advocacy by artists and architects for revitalization of the L'Enfant plan for Washington. Adjacent to the Octagon was the Lemon Building where, in the decade following the presentation of the Senate Park Commission plan in 1902, the Rock Creek Parkway Commission, the Lincoln Memorial Commission, and the Fine Arts Commission established their headquarters. The War Department's Office of Public Buildings and Grounds, which had legal authority over development in Washington and daily faced pressing pragmatic problems, also had offices in the Lemon Building. The White House was two blocks away; the Office of Supervising Architect in the Treasury Department three blocks away; and the Cosmos Club, four blocks away. It is unlikely that any other area in the nation possessed such a concentrated collection of professional, political, and social organizations. It is certain that this concentration made coordination easier, and response time quicker, both important in the crusade over Washington's future. As the 1890s ended, Brown met with McKim at the Century Club in New York to talk about Washington's future. Brown later recalled that McKim "lauded the beauties of the L'Enfant plan . . . and urged the feasibility of returning to it in the future development of the city.... McKim forcibly expressed his regret that this great plan should be destroyed by indifference and want of knowledge. Then we discussed the great need of a commission to study and plan a scheme for the future growth of the National Capital. I left him determined to make a demonstration that would arouse the attention of thoughtful people to the crime our nation was committing." [21] At its first meeting in the Octagon on 5 January 1899, just five days after the AIA had moved its headquarters there from New York, the AIA board of directors authorized publication of a quarterly magazine, The American Institute of Architects Quarterly Bulletin, which Brown would edit. [22] From the magazine's first issue in April 1900 until its last in 1913, the status of Washington's development was a frequent subject. The magazine was initially sent to all members of the AIA and to forty-three foreign societies, forty American societies and institutions, and fifty-nine periodicals in the field. Both its circulation base and influence expanded over the next 13 years.

The year 1900 was an important one in Washington, for it marked the centennial of the federal governments move from Philadelphia to its permanent seat in the District of Columbia. Numerous plans were being formulated to celebrate, not just with parades, but with commemorative building. Suggestions included a Centennial Avenue which would run from the Capitol diagonally across the Mall to the Potomac River, where it would cross the river on a memorial bridge. Enlarging the White House was a second important proposal. Both projects would become major points of discussion at the AIA's annual convention in 1900, to be held in Washington. One convention session was earmarked for discussion of federal buildings and their grouping. In March Brown wrote architects Thomas Hastings and Cass Gilbert, asking them to present papers. Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. was evidently asked at the same time. Henry Van Brunt, architect and president of the AIA in 1899, was asked to participate, but he was in Europe and would not return in time. On 18 May sculptor John Quincy Adams Ward declined Brown's invitation to present a paper while "thanking you for the opporrunity." [23] From the beginning, Brown's intent was to have architects, landscape architects, and sculptors participate, each approaching the subject of "grouping buildings" from the point of view of his respective profession. Even as convention sessions were being planned, drawings that could be exhibited during the convention were sought. These included the University of California competition sponsored by Phoebe A. Hearst. [24] The firm Boring & Tilton supplied drawings of their work at Ellis Island; George Browne Post loaned drawings of the proposed Justice Department building in Washington; and Hornblower & Marshall drawings of the Baltimore Custom House. These were exhibited at the Octagon, and at the Cosmos Club while the AIA convention was in session. [25] McKim's firm was asked on 22 June to participate. "Be kind enough to let me know if you or Mr. Mead or Mr. White will not prepare such a paper," Brown wrote. Brown noted that the convention would be in early December in Washington and that "Mr. F. L. Olmsted, Jr., has agreed to give a paper on the Landscape feature of the project." McKim held his reply until 31 July, when he responded that he would be sailing for Europe the next day, and could neither participate nor attend the convention. "I wish that it were in my power to contribute to the occasion," he wrote. A May letter to architect Howard Walker asking him to be a presenter finally reached him in Italy and he replied on 12 June accepting. [26] Walker noted that he had already visited Amsterdam, Munich, London, Rome, Venice, Budapest, Milan, and many smaller cities, and would be going to Paris, Dresden, and Berlin "with a view to studying municipal improvements." Brown, requesting a paper from architect Edgar V. Seeler, wrote: "It is intended by these papers to call the attention of Congress forcibly to the need of some harmonious scheme to be followed in the future development of Washington. We propose to have the reading and discussion open to the public and invite all Congressmen and officials to attend." Brown continued: "I will be pleased to furnish data about the original scheme of the city and buildings, as well as get you maps or other information you may desire." [27] During July 1900 Brown continued to contact possible participants. He asked Daniel Burnham, William A. Boring, Cass Gilbert, and Thomas R. Kimball, noting that "we propose to make a prominent feature of papers on the grouping of Federal Buildings in Washington City." [28] Gilbert did participate and Boring and Kimball attended the convention. Burnham, however, was too busy to attend. The sculptor H. K. Bush-Brown agreed, when Brown asked him, to prepare a paper. [29] When the program was set, Brown organized the papers in a session entitled "On the General Subject of the Grouping of Government Buildings, Landscape, and Statuary in the City of Washington," to proceed from general to specific topics. Walker delivered a paper on the topic of "Grouping of Buildings in a Great City" and Seeler one on "Monumental Grouping of Buildings in Washington." Olmsted spoke on "Landscape in Washington" and Bush-Brown on "Sculpture in Washington." Walker and Seeler were both MIT graduates and practicing architects as well as teachers of architecture. All four speakers had traveled abroad, were well known in their professions, and well known public speakers. Also in July 1900 Brown sent speakers background information. He noted in a letter to Olmsted that he was sending:

In September Brown and the Committee on Arrangements "determined to fix the 12th, 13th, 14th, and 15th of December as the days of the convention." The 12th was the day on which the Centennial would be celebrated. Brown wrote that including the 12th in the convention calendar would "give an opportunity to all architects who wish to see the different sights connected with the Centennial" and "follow it up by the Convention the next three days." [31] On 22 September Brown wrote Bush-Brown alerting him to Brown's "Suggestions for the Grouping of Buildings, Monuments, and Statuary, with Landscape in Washington," appearing in the Architectural Review. Brown noted that it was "written . . . as a preliminary to our convention work, thinking it might serve to call attention to the subject." He wrote again, after queries from Bush-Brown, that "we wish to call the attention of Congress to the fact that a grouping or massing of landscape, sculpture and buildings would be a great addition to the Capital City; also that a Commission should be appointed composed of architects, landscape architects, and sculptors to consider the subject, before any one of the schemes at present under consideration should be adopted." [32] Brown suggested emphasizing the importance of establishing an art commission to oversee development within the city and he stressed the importance of "not having it [the commission] dominated in any way by the Army engineers." Bush-Brown rewrote his speech in accordance with Brown's suggestions, but he still wanted to confer with Walker, who would not return from Europe until November, in case Walker might desire changes also. He agreed with Brown that the "several papers should compliment each other." They exchanged papers and Seeler modified his after reading Walker's. [33] All participants were invited to Washington to tour the area under discussion; Brown wanted no surprises and no deviations. He wanted each speaker to have extensive background material that included knowledge of the views of the other presenters and also familiarity with the locations in question. These areas included the White House and Ellipse, Capitol Hill, the Mall to the Potomac River, and areas abutting the south and north sides of the Mall. On 21 November Seeler sent Brown a copy of his speech noting that in preparing it, "the tour over the ground under your guidance a couple of weeks ago was of the greatest assistance to me." [34] Olmsted would already have been familiar with the area, and the others either toured it earlier or did so before the convention. In October, Brown had called the attention of his speakers to an article in the November Ladies Home Journal by Col. Theodore Bingham relating his plans for the enlargement of the White House. The article included a drawing that showed massive, multistory wings that clashed with the style of the original White House, and also dwarfed it. [35] Gilbert responded almost immediately, noting that the convention "would seem to me a very proper occasion . . . to take the matter up officially and see what action could be taken to preserve this fine old public monument." Boring replied humorously that he would "purchase now the first number of this valuable periodical that I have ever invested in, and hope to be much edified by Colonel Bingham's Architecture." Olmsted, too, sought out the magazine. [36] This solidified a second motive of the 1900 convention, to wrest control of the White House from Bingham and the Army engineers and foil the proposed enlargement. Bingham was preparing a model of his proposed addition to the White House and was asked to lend it to the AIA for exhibition during the convention. He replied that he could not "assist your committee with designs for the White House and treatment of the Mall" because the drawings would not have been officially published by then. He did, however, thank Brown for the invitation to attend the session, which he noted he would "be glad to accept, if possible." When pressed to lend the model, Bingham responded "in order to make clear the position of this Office in the matter, your attention is respectfully called to the fact that the work being done in this Office in regard to an extension to the Executive Mansion is entirely official in its character, and is, therefore not subject to general inspection by law and regulations until it has been officially made public." [37] Bingham's model was actually exhibited, but at the White House (12 December 1900), where he explained it to the guests assembled for the centennial celebration. Discussions on illustrating the AIA session were extensive, with Brown offering to produce lantern slides, either from materials provided by the speakers or from other sources. In August and early September 1900, Brown and Joseph C. Hornblower of the AIA's Washington chapter traveled to Europe to attend the Paris Exposition. "I procured a large collection of photographs," Brown wrote, "covering sculpture, landscape and buildings and their combinations which, in form of lantern slides, we could use in our crusade." [38] These photographs were reproduced as lantern slides and many of them were used in lectures at the 1900 convention. They also appeared in the published papers of the convention and in the 1902 Senate Park Commission report. These and other lantern slides from the Senate Park Commission's report were, between 1902 and 1913, frequently used in prepackaged slide lectures distributed across the nation in support of the commission plan for the Mall. The dean of Washington architecture, Hornblower, would chair the 13 December session on grouping Washington's public buildings and introduce the individual speakers. A former student of Jean-Louis Pascal in Paris, Hornblower had served as president of the AIA's Washington chapter in 1897 and was on the faculty of the School of Architecture at Columbian University [now George Washington University] since 1897. He and his partner, James Rush Marshall, had won the Baltimore Custom House competition in 1900 and, in 1904, they were commissioned to design the Smithsonian's National Museum (Natural History Museum), one of the first two buildings on the Mall to respond to the parameters established by the Senate Park Commission's report. [39] Three other architects were asked to prepare responses to the principal papers: Cass Gilbert of New York, (initially asked to be a speaker), Paul J. Pelz, and George Oakley Totten Jr., the last two both prominent Washington architects. When Pelz replied affirmatively, he noted that he had "as a member of the Board of Trade given this subject [grouping buildings in Washington] some study...and [had] produced a suggestive plan to that effect which met the unanimous approval of the Com. on Publ. Bldgs. of the Board of Trade." [40] The discussants were well known to the national AIA audience, and all had designed major government buildings. Gilbert's New York Custom House was already considered a modern masterpiece. Totten had been the chief designer in the Office of the Supervising Architect of the Treasury, designing the Philadelphia Mint and several post offices, before opening a Washington office in 1898. Five years earlier he had won the McKim Traveling Scholarship and attended the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. He also served as president of the Washington Architectural Club from 1897 to 1898. Pelz, in partnership with John L. Smithmeyer, had designed the Library of Congress (1871-97), which brought Beaux-Arts design to Washington and was much in the public eye in 1900. [41] Everything was ready for the beginning of a battle with Colonel Bingham and the Army engineers, with the first skirmish set for the White House celebration on 12 December. Brown had been invited by President and Mrs. William McKinley to "an informal luncheon following the exercises at the Executive Mansion." [42] It is probable that at least the AIA convention speakers and AIA officers were also invited to the luncheon, for George Browne Post telegraphed Brown, "I accept luncheon invitation with pleasure." [43]

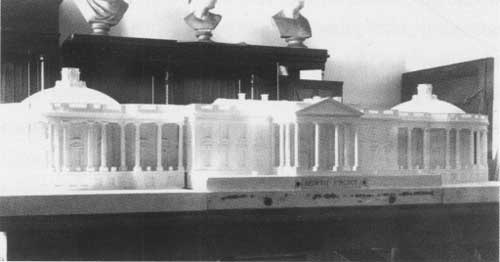

Celebration of the 100th anniversary of the establishment of the seat of government in the District of Columbia took place officially on 12 December 1900. President McKinley met the state governors and other guests in the White House's Blue Room, where they were presented by Colonel Bingham in his official capacity as the president's aide. All were ultimately seated in the East Room where, "on a raised decorated platform in the center was a plaster model of the Executive Mansion with the proposed additions." (fig. 5) Bingham, the engineer officer in charge of Public Buildings and Grounds, delivered an address on the history of the Executive Mansion during the nineteenth century. He spoke principally on the proposed enlargement of the Executive Mansion, which, he noted, he had begun to study in 1897. He lauded his plan for retaining the original building, asserting his extensions would accentuate the character of Hoban's original design by being architecturally harmonious with it. The rationale for the extensions was to relieve the pressure of use on the building for the next quarter century. He closed his address by stating "We have endeavored to imbue ourselves with a part, at least of the spirit of the first architect of this house and have worked for the entire country; and if these results please you, its representatives, that is our sufficient reward." [44]

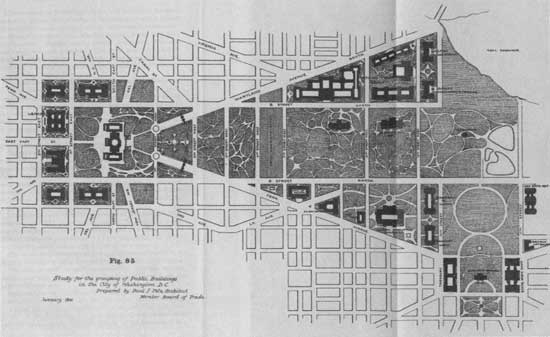

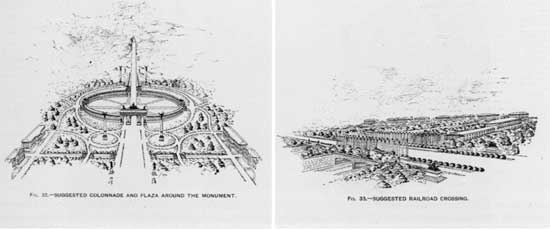

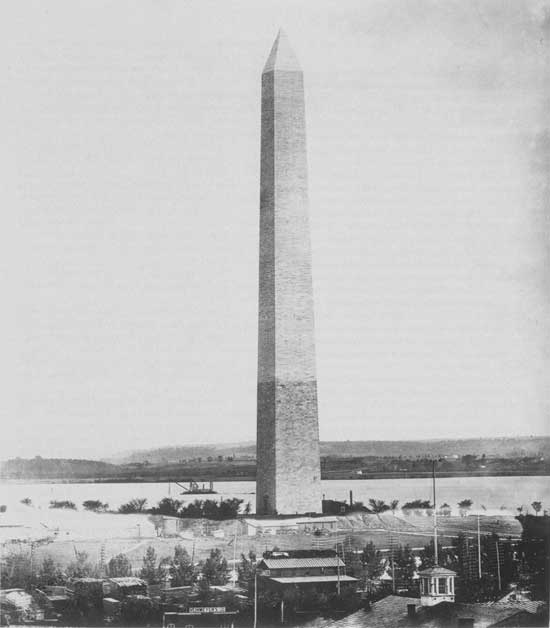

The next day, 13 December, at the opening session of the AIA convention, AIA president Robert Peabody started that "if the White House in which we all take such pleasure and pride, needs to be increased in size, we want . . . [the work] carried out by the best artistic skill that the country can produce and by nothing less efficient." On the following day the convention adopted a resolution on the White House aimed at preventing its disfigurement "by allowing its proposed enlargement to be carried out by parties unfamiliar with architectural design." The convention voted overwhelmingly for the resolution. [45] Two days earlier the Fine Arts Union of Washington, another AIA ally, had protested against Bingham's design to the House and Senate committees on Public Buildings and Grounds. The group wrote that "[the Union] wishes to call your attention to the enclosed protest and recommendations from various Art societies in reference to additions to the Executive Mansion and request your earnest consideration of the same." [46] Brown, through the Public Art League, had collected protests from forty art associations around the country, from local AIA chapters, and from individual architects. These, too, were presented to the congressional committees. [47] Brown also took advantage of the national press's presence in Washington because of the centennial celebrations and distributed information packets about the nationwide protests to the reporters. [48] Also on 14 December the Washington Board of Trade resolved to support a commission to study the future development of the capital city. [49] Philadelphia's T-Square Club, an architectural society and AIA supporter, followed on the 20th with a resolution demanding that any White House changes take place only after a professional commission had been appointed and had agreed to the change. [50] Brown later wrote that "the people were interested in keeping intact their historic Presidential home and responded to the appeal for its preservation. McKinley listened to the public demand and ordered the model removed from the East Room. It was stored in the cellar of the Corcoran Gallery and neither [Bingham's] scheme nor model was heard of again." [51] Because Brown was the recognized scholar on the Capitol and White House his criticism was taken seriously. While confronting the White House issue, the AIA simultaneously considered the future development of Washington, when on Thursday evening 13 December the convention opened the floor to discussion of grouping government buildings on the Mall. In his opening remarks Hornblower gave a short history of planning in Washington, noting that L'Enfant's plan was not derivative but original. He suggested that the plans which would be proposed at the convention for the Mall might have credit, but he suggested that all should be questioned until a "more comprehensive study has been made of the whole matter of arrangement of parks and disposition of buildings." He suggested public buildings for the triangle between Constitution and Pennsylvania avenues, and a building for the Supreme Court. "The plan of the city as originally projected has been sufficient for the requirements of [its] first century. Now, at the end of the first . . . it is proper to consider fully and studiously the requirements of the second." [52] Olmsted discussed existing landscape features of the area, especially the Mall: "The solution of the general problem involved in the revision of the Mall demands months of careful study and consideration by able and appreciative men, while the suggestions given here are the crude produce of a few days' thought. But one thing is clear: The fundamental importance of living up to the greatness of the original plan." [53] Architect Howard Walker illustrated his presentation with slides from European cities, most of them the capitals of their countries. "It is apparent," he asserted, "that the most attractive cities are those where some broad comprehensive plan of treatment has been conceived and adhered to, and when if poor surroundings or inferior architecture forced itself into prominence, its effect was minimized either by planting out with trees or by interrupting continuous vistas by a monument or building." He recommended extending the White House and Capitol vistas beyond the Washington Monument to the Potomac River. [54] Edgar Seeler began his presentation with a history of Washington's founding, ending with: "This, then, is a site selected after much thought and conscientious deliberation by Washington, a plan developed under his guidance by the foremost engineer of the time; the whole endorsed by Jefferson and Madison and the territorial commissioners. A plan which, in its essential scheme, the intervening years have stamped with their approval. And yet a plan which was practically forgotten after the Capitol and White House were located until within a few years. . . . We architects are just beginning to see that there is a mission for our organization." Seeler suggested the following criteria for a new plan: strict height limitations along Pennsylvania Avenue; retaining only the Smithsonian Institution and Washington Monument among the Mall's structures; the construction of a memorial bridge on a direct axis from the Capitol through the Washington Monument; removal of the railroad station from the Mall; purchasing the triangle between Sixth and Fifteenth streets and Pennsylvania Avenue and North B Street (now Constitution Avenue) for federal construction; placement of buildings on the outer limits of the Mall; and the formation of a Commission of Fine Arts. "The American Institute of Architects should pledge itself to the formation of a commission, powerful, authoritative, and beyond question in its judgments, in whose hands the artistic development of the city of Washington shall be placed, and whose decisions shall be without recourse." In discussing the proposed memorial bridge on the Capitol-Washington Monument axis, he suggested that "at the transition from boulevard to bridge should be a vigorous architectural accent—a memorial or monumental group." [55] Sculptor H. K. Bush-Brown, reminded the convention in his speech "Sculpture in Washington," that monuments were erected to "keep alive in the mind of the community the ideals that have moved the souls of men in the past. Commendable as are the monuments in Washington, do we find that any plan of selecting subjects or grouping them has been adopted? No, quite the contrary. . . [but] art made Athens and Rome and Florence and Venice, each in turn, the center of the world. . . . We have in Washington one of the finest city plans in the world...." Bush-Brown also suggested formation of a fine arts commission, noting that "to judge of military tactics and national policies requires years of training and experience. Is it too much to assume that art is worthy of the same consideration?" [56] After the AIA meeting Olmsted wrote Brown that "as to forwarding the movement for doing the right thing at Washington, I doubt if such meetings have any very considerable weight except as they may set a few people to work to personally talk to the right people in just the right way." He warned that Bingham would be a problem and that Secretary of Agriculture James Wilson was "distinctly hostile." [57] The AIA convention directed Peabody to appoint a special committee of seven members to consider the formation of an art commission "to advise regarding the improvement of the National Capital." William A. Boring of New York was appointed as chairman of the first of these committees, with its members including G. F. Shepley from Boston, Frank Miles Day from Philadelphia, W. S. Eames from St. Louis, Edward Green from Buffalo, Joseph C. Hornblower from Washington, and George Browne Post from New York its members. Eames was appointed to chair a second committee, with Post and R. W. Gibson of New York as members asked to communicate to Congress the AIA resolutions regarding the White House. [58] These AIA committees met with Senator McMillan's aide Charles Moore almost immediately, and on 19 December, just six days after the papers had been read to the convention, McMillan introduced a congressional resolution to print the AIA papers as a Senate document. Printed as a government document the AIA papers and their viewpoint would become available to architects nationwide and abroad. [59] The publication would be sent to AIA members, forty American societies and institutions, forty-three foreign societies, and to fifty-nine periodicals on architecture and the allied arts. Equally important, the collected papers would be accessible to politicians at all levels. Moore, in his introduction to the convention papers, noted that "The Report of the Centennial Celebration, now in press, will show the ideas of the laity; this publication contains the tentative plans of the experts," leaving no doubt where his and Senator McMillan's sympathies lay. [60] Brown's article from the Architectural Review of August 1900, although not read at the convention, was also included. This piece discussed a number of building topics: the proposed Centennial Avenue; future development in the triangles of land between Pennsylvania and Maryland avenues and the Mall; a memorial at the foot of the Capitol; another memorial on the banks of the Potomac on axis with the Capitol and the Washington Monument; a memorial bridge; and parkland in the area between the Washington Monument and the Tidal Basin. Rock Creek Park and the National Zoo (with four illustrations of Brown's own work) were suggested as parkland to be permanently preserved. Brown also mentioned railroads and the need to remove the existing station to the Mall's south side, with its entrances below street level and confined to Sixth and Seventh streets. To oversee all this, he wrote, "it appears to me that a carefully selected commission of architects, sculptors and landscape architects should be given charge of the subject." [61] The collected convention presentations by Gilbert, Totten, and Pelz on grouping buildings were labeled "discussion following the papers read before the Institute," although they had not actually been read. Gilbert had proposed building a new residence for the president on Meridian Hill, eighteen blocks north of the White House, allowing the older building to be used exclusively for offices. [62] Totten, in presenting his plan, acknowledged his indebtedness "to the inspiring writings of Mr. Glenn Brown. It is to Mr. Brown, I believe, more than to any other one person we are indebted for the revival of Major L'Enfant's beautiful scheme." [63] In the collected papers Pelz reported that a campaign to purchase all the property between Pennsylvania Avenue and the Mall had been suggested by the Washington Board of Trade in 1899, and had found support in the local press. He suggested a Treasury Annex along Fifteenth Street, NW, and at Center Market between Seventh and Ninth streets, today's National Archives, Pelz envisioned "a most central site between the Capitol and all the departments [suitable for] a hall of records." (figs. 6-11) [64]

On 17 December 1900 Boring, Peabody, and Brown met with Moore and the Senate Committee on the District of Columbia. Together they agreed on what would become Senate Resolution 139, authorizing the president to "appoint a commission, to consist of two architects and one landscape architect eminent in their profession, who shall consider the subject of the location and grouping of public buildings and monuments to be erected in the District of Columbia and the development and improvement of the entire park system of said District, and shall report to Congress thereon." [65] Boring recommended Peabody, Burnham, McKim, Post, and Olmsted as "suitable men to serve on such a commission." [66] Resolution 139 was introduced into the Senate that same day. It included an appended statement prepared by Brown stating: "Now is the time, on the hundredth anniversary of the foundation of the Capitol [sic] to consider the propriety of another plan on which future buildings shall be erected, by which parks shall be laid out so as to enhance the effect and beauty of the buildings, and by which groupings of monuments may add to the effectiveness of the whole." Almost immediately Boring's committee sent a letter to members and chapters suggesting that all possible pressure be brought to bear on the Congress to insure passage of the resolution. [67] Moore later recalled the subsequent events:

Internationally known sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens, a friend of Brown's and a wintertime resident of Washington, was added to the commission by McKim and Burnham. [69] During the lengthy discussion at the 19 March 1901 hearing, McMillan noted that the "architects . . . are as much interested in the park system as they are in the public buildings." [70] They wished the Senate Park Commission members to benefit from the professional opinions expressed by the authors of the talks and papers prepared for the AIA's convention in 1900. In his obituary in 1932 of Brown, Moore wrote that the Senate Park Commission's "textbook was Glenn Brown's History of the United States Capitol and the presentations he made of the fundamental and vital value of the L'Enfant Plan were instrumental in leading members of the Senate Commission to base their report and their plans on the plan L'Enfant had designed and George Washington had approved, and which was already the underlying plan of the capital." [71] In discussing efforts to insure the adoption of the Senate Park Commission plan, the AIA magazine asked in an editorial of 1913: "Why should individuals band themselves together into societies? Is personal benefit the object?" The editorial went on to answer: "The basis of such association should be public service, not individual gain, otherwise it were much better not to organize." [72] The last decade of the nineteenth and first decade of the twentieth centuries certainly provide one of this country's best examples of continued public service by artists and architects. It has never since been equaled.

I should like to thank James F. Olmsted, Sue Kohler, and Pamela Scott for their assistance, material, and leads as this essay was being written. 1John W. Reps, Monumental Washington: The Planning and Development of the Capital Center (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1967); Jon A Peterson, "The Hidden Origins of the McMillan Plan for Washington, D.C., 1900-1902," in Historical Perspectives on Urban Design: Washington, D.C., ed. Antoinette J. Lee, Conference Proceedings, 7 October 1983, Center for Washington Area Studies, Occasional Paper No. 1; Sue A. Kohler, The Commission of Fine Arts, A Brief History, 1910-1995 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1996; Sue A. Kohler, "Artists and Architects in Government Planning: The Beginnings of the Commission of Fine Arts," a paper read at the National Collection of Fine Arts (today's Smithsonian American Art Museum) symposium, Art in Washington: Some Artists, Patrons, and Institutions in the Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries, 15 May 1980. Kohler, as the title of her paper suggests, has looked more closely at the involvement of artists and architects locally and nationally in the Senate Park Commission and Commission of Fine Arts movements than have other authors. 2Antoinette J. Lee, Architects to the Nation—The Rise and Decline of the Supervising Architect's Office (New York: Oxford University Press, 2000), 163-88. 3American Institute of Architects Archives 801/1.2B, "Bureau of Architecture, 1875-76." This Record Group also contains files on President Theodore Roosvelt's later creation, by executive order, of a "Council of Fine Arts/Bureau of Architecture, 1908-09." 4Glenn Brown, Memories, 1860-1930: A Winning Crusade to Revive George Washington's Vision of a Capital City (Washington, D.C.: W. F. Roberts, 1931). This is a basic source on Brown's efforts and those of the AIA to reestablish the L'Enfant plan for Washington; William Brian Bushong, "Glenn Brown, The American Institute of Architects, and the Development of the Civic Core of Washington, D.C.," (Ph.D. diss., George Washington University, 1988). This is the best biography of Glenn Brown and the most complete study of the involvement of the American Institute of Architects 1890-1913 in the evolution and carrying out of the Senate Park Commission plan for Washington. 5William Brian Bushong, Judith Helm Robinson, Julie Mueller, A Centennial History of the Washington Chapter of The American Institute of Architects, 1887-1987 (Washington. D.C.: Architectural Foundation Press, 1987). This study of a major Washington. D.C., organization, of which Glenn Brown was a founder and important member, contains important data on the work of Brown and the chapter in focusing national attention on the L'Enfant and Senate Park Commission plans. It also offers good, short biographies of most of the Washington architects mentioned in this paper. 6Bushong. "Glenn Brown," 8-15; Brown, Memories, 87-88 (Chamberlain); 91-95 (Slayden); 497-99 (Page). 8Bushong, "Glenn Brown," 8-39, for a survey of Brown's training and practice; 295-301 for a list of his projects. 9Glenn Brown, "The Tayloe Mansion, The Octagon House, Washington, D.C.," American Architect and Building News 23 (7 January 1888): 6-7. Glenn Brown, "Dr. William Thornton, Architect," Architectural Record 6 (July 1896): 52-70. 10Glenn Brown, The History of the United States Capitol, 2 vols. (Washington. D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1900-1903). 11Cass Gilbert, foreword to Glenn Brown, "Roosevelt and the Fine Arts," American Architect, 116 no. 2294 (10 December 1919): 709-10; Brown's article appears in two parts: "Roosevelt and the Fine Arts, Part 1," in ibid., 711-19, and "Roosevelt and the Fine Arts, Part 2," in ibid., 116 no. 2295 (17 December 1919), 739-52. Brown, Memories, 138-77. 12Glenn Brown, "The Selection of Sites for Federal Buildings," American Architect 3 no. 4 (August 1894): 27-29. The first sentence of this article became the first sentence of Brown's The History of the United States Capitol, and its title provided the theme for the American Institute of Architects Convention of 1900. 15AIA Archives 509/2, "American Institute of Architects Board of Directors, Minutes," 16 January 1896; AIA Archives 505, "American Institute of Architects Proceedings, 30th Convention, Nashville, Tennessee, 20-22 October 1896." 16AIA Archives 505, "American Institute of Architects Proceedings, 31st Convention, Detroit, Michigan, 29-30 September. 1 October 1897." 17AIA Archives 505, "American Institute of Architects Proceedings, 32d Convention, Washington, D.C., 1-3 November 1898." 18AIA Archives 501, "American Institute of Architects, Constitution and By-Laws," 1898. 20The Historical Society of Washington, D.C., Archives, "The Washington Society of Fine Arts Yearbook, 1914." 22AIA Archives 505, "American Institute of Architects Proceedings, 33d Convention, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, 13-16 November. 1899," 18. 23AIA Archives 801/1/17/1900H, Thomas Hastings to Glenn Brown, 26 March 1900; 801/1/17/1900G, Cass Gilbert to Brown, 31 March 1900; 801/1/17/1900N—O, Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. to Brown, 2 April 1900; 801/1/17/1900N—O, Olmsted to Brown, 1 May 1900; 801/1/17/1900U—Z, Henry Van Brunt to Brown, 13 April 1900; 801/1/18/1900U—Z. John Quincy Adams Ward to Brown, 18 May 1900. 24AIA Archives 801/1/18/1900T, Paul B. Tuzo to Brown, 18 May 1900, 16 June 1900, and 21 June 1900. AIA Archives 801/1/18/1900P, Brown to Robert Peabody, 18 June 1900, and return to Brown marked approved. 25AIA Archives 801/1/1/6/1A/91, Brown to Boring & Tilton, 22 June 1900; 801/1/1/6/1A/163, 14 July 1900; 801/1/1/6/1A/417, 8 December 1900. Correspondence with George Browne Post, Hornblower & Marshall, and others asked to supply drawings is similar and can be found in this letterbook. 26AIA Archives 801/1/1/6/1A/65, Brown to Charles F. McKim, 22 June 1900; 801/1/17/1900/L—M, McKim to Brown, 31 July 1900; 801/1/18/1900U—Z. Howard Walker to Brown, 12 June 1900. 27AIA Archives 801/1.1/6/1A/84, Brown to Edgar V. Seeler, 16 June 1900; 801/1/18/19008, Seeler to Brown, 9 July 1900. 28AIA Archives 801/1.1/6/1A/130, Brown to Daniel Burnham, 6 July 1900. In the same letterbook records identical letters to Thomas Kimball on 128, to Gilbert on 129, and to Boring on 131. 29AIA Archives 801/1/17/1900B, Burnham to Brown, 4 December 1900; 801/1/17/1900B, H.K. Bush-Brown to Brown, 14 July 1900. 30AIA Archives 801/1.1/6/1A/152, Brown to Olmsted, 12 July 1900. 31AIA Archives 801/1.1/6/1A/295-98, Brown to R. S. Peabody, 15 September 1900. 32AIA Archives 801/1.1/6/1A/324, Brown to Bush-Brown, 22 September. 1900; 801/1.1/6/1A/373, Brown to Bush-Brown, 11 September 1900. 33AIA Archives 801/1.1/6/1A/389, Brown to Bush" Brown 18 October 1900; 801/1/17/1900B, Bush-Brown to Brown, 27 October 1900; 801/1/18/19005, Seeler to Brown, 1 December 1900. 34AIA Archives 801/1/18/1900S, Seeler to Brown, 21 November 1900. 35AIA Archives 801/1/18/1900S, Brown to Seeler, 29 October 1900. Other speakers were also notified, as were Cass Gilbert, E. B. Green and Wm. A. Boring. 36AIA Archives 801/1/17/1900G, Gilbert to Brown, 31 October 1900; 801/1/17/1900B, Boring to Brown, 31 October 1900; 801/1/17/1900N—O, Olmsted to Brown 8 November. 1900. 37AIA Archives 801/1/17/1900B, Col. Theodore Bingham to Brown, 13 November 1900; 801/1/17/1900B, Bingham to Brown 15 November 1900. 39Bushong, Centennial History, 132. 40AIA Archives 801/1/18/1900P, Paul Pelz to Brown, 4 December 1900. 41Bushong, Centennial History, 168. 42AIA Archives, Glenn Brown Papers 804/5/5A. The invitation and other materials concerning Brown's relations with presidents William McKinley, Theodore Roosevelt, and William Howard Taft are in this collection in 804/5/4, 804/5/5A, 804/5/SB, and 804/5/SC. 43AIA Archives 801/1/18/1900P, Post to Brown, 11 December. 1900. This clearly refers to the White House luncheon since Post noted, "I arrive in Washington tonight. Must return to New York tomorrow night." 44William V. Cox, comp., 1899-1900 Celebration of the One Hundredth Anniversary of the Establishment of the Seat of Government in the District of Columbia, (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1901), 59, 60-64. 45AIA Archives 509, "American Institute of Architects Proceedings, 34th Convention, Washington. D.C., 12-15 December 1900," 3, 112. 46Nationals Archives and Record Administration (NARA) HR 56A—H23.1, "Letter with enclosed protests," Theodore F. Laist, Secretary of the Fine Arts Union of Washington, D.C., 11 December. 1900. The President of the Union is listed on its letterhead as Glenn Brown, the organization address given as The Octagon. 49Washington Board of Trade Records, "Minutes," 14 December. 1900, George Washington University, Gelman Library, Special Collections Division. 50NARA HR 56A—H23.1, "Resolution," T-Square Club of Philadelphia, 20 December. 1900. 52Glenn Brown, comp., Papers Relating to the Improvement of the City of Washington. (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1901) 13-21. 53Brown, Papers, 33; for Olmsted's entire speech see 22-34. 54Ibid., 44; for Walker's entire speech see 35-47. 55Ibid., 49; for Seeler's entire speech see 48-58. 56Brown, Memories, 77; for Bush-Brown's entire speech see 70-77. 57AIA Archives 801/l/10/1901N—O, Olmsted to Brown, 13 December. 1900. 58AIA Archives 505, "American Institute of Architects Proceedings, 34th Convention, Washington, D.C., 12-15 December. 1900," 120. 59The American Institute of Architects Quarterly Bulletin 1 no. 4 (January 1901): 162. 61Ibid., 62. For Brown's entire paper, reprinted from the August 1900 Architectural Review, see 59-69. 62Brown, Papers, Gilbert's plan appears between 80-81. 66AIA Archives 509, "American Institute of Architects Board of Directors, Minutes," 7 January 1901. 67AIA Archives 801/1/2B/2.1, papers concerning Resolution 139. 69"Informal Heating Before the Subcommittee of the Committee on the District of Columbia, United States Senate, Park Improvement Paper No. 5," in Park Improvement Papers: A Series of Twenty Papers Relating to the Improvement of the Park System of the District of Columbia, ed. Charles Moore (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1903). 70Park Improvement Papers, ed. Charles Moore, 5, 69. 71Charles Moore, "Glenn Brown," Journal of the Royal Institute of British Architects 15 (October. 1932): 39. 72Unsigned editorials, Journal of the American Institute of Architects 1 no. 2 (1913): 59.

Last Modified: March 20, 2009

|