|

Contents

|

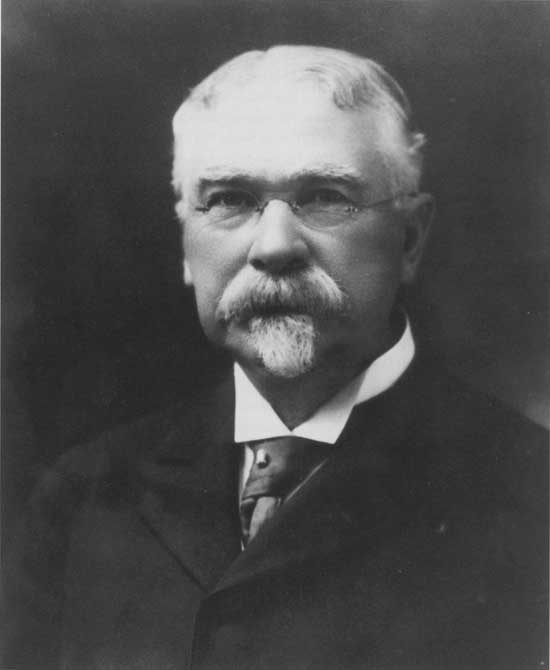

The Senate Park Commission Plan for Washington, D.C.: By Jon A. Peterson [1] THE 1901 to 1902 Senate Park Commission plan for Washington, D.C., ranks among the most significant urban plans in American history. Its novel blending and adroit elaboration of city-making ideas then current in the United States made it a benchmark for modern urbanism and triggered a national city-planning movement. The consummate artistry and professionalism of its designers, together with their boldness of vision and willingness to address local needs, established its potential benefit to the national capital. Ultimately, the plan-makers' deep and enduring commitment to implementation, fortified by the tactical shrewdness of their backers—and their plain good luck—in negotiating Washington politics, against a backdrop of mounting public support, brought success: a capital city recast as a symbol of national authority and of the nation's emergence as a world power. All of these considerations, taken together, establish the importance of the Senate Park Commission plan, often called the McMillan Plan after its sponsor, James McMillan of Michigan, chairman of the Senate Committee on the District of Columbia from 1890 until his death in 1902 (frontispiece). [2]

A design of such note might be presumed to reflect a strong, well-established urban planning tradition in the United States. But this was not the case. Since the mid-eighteenth century, most American towns and cities had been laid out on grids by a society more eager to promote land sales than civic order. And big-city growth, once it had begun on a sustained basis from the mid-nineteenth century onward, had occurred in boom-and-bust surges subject to little or no public regulation. Everywhere in the United States, market forces had set the terms of growth, in land subdivision at the city's fringe and in building up the city proper: its stores, shops, offices, factories, and private residences. In transportation, the powerful railroad corporations that had tied the nation's towns and cities into vast networks by the 1880s, and the city transit firms that had laced urban America with trolley lines in the 1890s had dictated the routes and hence the directions of city growth. During the Gilded Age, large-scale, systematic public planning for existing cities had focused on water supply, sewerage systems, and public parks. Because these services, though urgent, had offered scant opportunity for profit, they usually had been addressed by public authorities as specialized interventions. As to generalized planning for all aspects of the built city, or what is now called comprehensive city planning, it was all but unknown in the United States of 1900.

To all of this, one city stood out as a partial exception. Alone among major urban centers in the United States, Washington rested on a grandly conceived foundation. In 1791 Pierre Charles L'Enfant, in the employ of President George Washington, had conceived the capital as the seat of a "vast empire," designing it as an enormous grid of streets crisscrossed by wide diagonal avenues. The many points of crossing and convergence had, with artful forethought as to placement, yielded over two dozen public squares and spaces and, together with the avenues, had made the city a symbol of nationhood. By 1900 the capital had filled out its frame, but the Victorian city that had emerged differed fundamentally from L'Enfant's and Washington's vision. When the Mall as the physical and symbolic heart of L'Enfant's plan began to be developed in the 1840s, the neoclassical design principles of harmony and regularity that had guided him had given way to ones predicated on irregularity and intricacy derived from medieval art. L'Enfant had envisioned the Mall as a partially sunken, axial corridor lined by museums and theaters and extending about a mile due west from Capitol Hill. This major axis would have formed the stem of a vast, L-shaped public space, its crossing arm running due south from the President's House. L'Enfant had marked this juncture point with an equestrian statue of George Washington (pl. I). Yet in 1848, Robert Mills' obelisk monument was placed well away from that point, in the middle of the central vista between James Renwick's Smithsonian Institution, begun on the south side of the Mall in 1847, and a canal, which occupied a wide swath along the Mall's north side. Although the Mall still looked like "a marshy and desolate waste," these structures, in concert with the Botanic Garden at the foot of Capitol Hill, would soon define the western "vista" when viewed from the Capitol terrace. Picturesque landscaping for the Mall was considered as early as 1841 and began to be carried out in 1851, to the plans of America's most prominent landscape gardener, Andrew Jackson Downing, filling L'Enfant's corridor with dense tree plantings of many species. The monument itself, built to a height of 170 feet by 1855, remained an unfinished shaft for the next quarter of a century, as if representing the city itself. [3] By 1900 the Mall had become a chain of individual public parks, each associated with a different Victorian building, most of them built of red brick. The passenger shed of the Victorian gothic terminal of the Baltimore and Potomac Railroad, built in 1873 to 1878, extended nearly halfway across the Mall at Sixth Street; the canal had been filled during the 1870s. [4] (See Helfrich fig. 3 and Wrenn fig. 6) Beyond the tracks, from Seventh to Twelfth streets, lay the picturesque grounds of the Smithsonian Institution, where a multitude of footpaths meandered through a forest of trees (fig. 1). From Twelfth to Fourteenth streets, the Agriculture Department maintained an open and formal parterre in the center of the Mall, but extensive greenhouses and sheds to the west of its building struck resi dents and visitors alike as an eyesore. (See Dalrymple fig. 4) Terminating the chain, scattered clumps of trees dotted the meadow around the Washington Monument, completed in 1884.

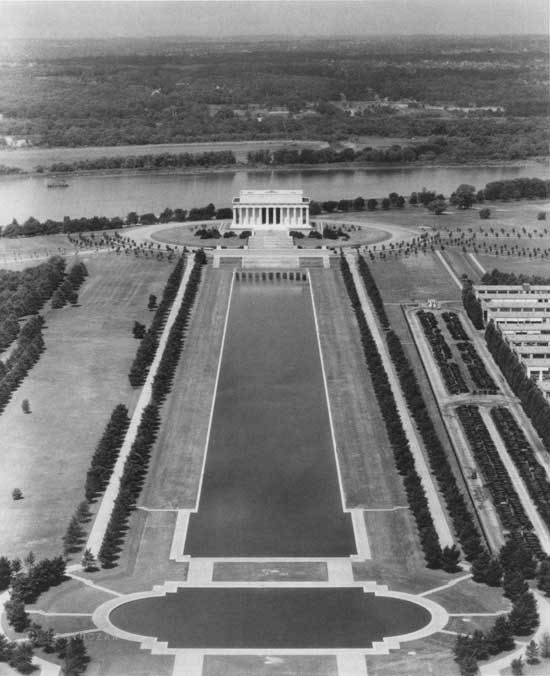

By 1900, to the west and southwest of the Monument lay "Potomac Park," a 739-acre swath of newly made public ground that, as landfill, covered the old tidal flats of the Potomac River. This project, begun in 1882 by the Army Corps of Engineers, included a long spit of land stretching southeastward along the eastern bank of the Potomac, later named East Potomac Park. [5] What was to be done with this new land and its connections, if any, to the Mall park chain had not been decided (pl. XVI). Washington itself by 1900 had become a city of considerable stature. From a population of 75,000 in 1860, it had grown to 278,000. Beginning in 1871 the city center and its built-up neighborhoods acquired their first modern infrastructure, including gas and electric lines, water and sewer service, and street paving. These improvements, initiated during the city's brief territorial government (1871-74), had continued under a board of commissioners directly answerable to Congress. Inevitably, the various House and Senate committees on the District of Columbia that oversaw the city's day-to-day affairs, along with other committees that designated sites for new federal and city buildings or privately sponsored monuments, exerted a fragmented and unpredictable control over Washington's development. For example, beginning in 1892 to 1893, Congress, after years of splitting costs with local taxpayers, suddenly refused to finance the extension of streets and squares into the "county" lands lying between the city's original boundary and the District of Columbia line. Nonetheless, Washington by the 1890s was increasingly perceived as a source of national pride, especially for its government buildings, many of which contained small museums or spaces commemorating American achievements, none more lavishly than the new Library of Congress. Against this backdrop, the Senate Park Commission plan when displayed at the Corcoran Gallery for nearly six weeks beginning in mid-January 1902, drew rapt attention. On view, first and foremost, was a spectacular design for the city's core, featuring the Mall as a two-and-one-half-mile-long corridor, beginning at the foot of Capitol Hill and extending westward to reach what is now the Lincoln Memorial. Gone was the miscellany of verdant parks and grounds; gone was the railroad station; and gone also were all the brick and brownstone Victorian buildings along the Mall's southern edge, including the Smithsonian Institution. In their place, a unified green space controlled the scene, accented by parterre gardens, water basins, and monuments and flanked by rows of trees in front of new, white, neoclassical buildings—with everything located in concert rather than by happenstance (pl. VIII). [6] What the Senate Park Commission plan contemplated was a unified ceremonial core, scaled to early twentieth-century urbanism and reflective of a cosmopolitan vision of national culture. Besides the renewed Mall, the core scheme also included formal groups of public buildings around Capitol Square, around Lafayette Square just north of the White House, and between the Mall and Pennsylvania Avenue (an area now known as the Federal Triangle). The newly made Potomac Park contained two monuments, one to terminate the Capitol axis, the other the White House axis. Also integral to the core were a new union railroad station and a memorial bridge across the Potomac River. [7] A second phase of the plan called for a vast, new park system joining together the outer reaches of the city (pl. IV). From the Mall core, a shore drive ran along the Potomac River leading to a parkway through the valley of Rock Creek that connected to both a multilane boulevard and a beltway across the northern reaches of the city. These roads provided access to several federal sites, including Civil War forts and the grounds of the U.S. Soldiers Home. Further on, additional park and road connections led to the Anacostia River, and to an array of Civil War forts in the southeastern portion of the district, yielding a park chain that encircled most of the city. This phase of the plan also called for the inauguration of a playground system; the transformation of the malarial Anacostia flats into an immense water park; the more "sober treatment" and better regulation of Arlington cemetery; the preservation of the Potomac River palisades and the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal; the establishment of the Great Falls of the Potomac as a national park, of a quay for the Georgetown waterfront, and of a memorial drive to Mount Vernon. [8] The great puzzle of the Senate Park Commission plan is why a scheme of such remarkable sweep and boldness ever appeared. It followed no European model, despite specific borrowings from European civic and garden design. No American city had ever contemplated anything like it. It was, in fact, sui generis: a new and comprehensive vision for the capital and the nation. As such, it reflected an extraordinary convergence of events whose interactions could hardly have been forecast even twelve months earlier. And because it was so idealistically framed and swiftly formulated at a time of fiscal stringency, its prospect for survival and influence was anything but certain. Yet it had appeared in the one city whose planning had always been an American exception. The story, in outline, unfolded as follows. After several prominent Washingtonians, most of them members of the Board of Trade, had organized a lavish, patriotic celebration to mark the 100th anniversary of the federal government's move to Washington in 1800, their initiative became entangled with city-development issues sparked by a power struggle between Senator McMillan and the entrenched U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. The latter had held executive authority over public buildings and grounds, including the Mall, since 1867. The root question was how to eliminate dangerous railroad grade crossings throughout the city. The controversies that ensued placed the entire urban fabric at issue, most especially the civic core, establishing quite by accident the citywide and multipurpose character of the struggle and hence of the Senate Park Commission plan as its ultimate outcome. The American Institute of Architects (AIA), well into these controversies, seized hold of the 12 December 1900 centennial event to showcase their profession's most advanced ideas about civic art. Interested in much more than theory, they immediately allied themselves with Senator McMillan and the Board of Trade against the engineers to attain their goals in an unprecedented way: by means of a park system plan for the entire city. Once the Senate Park Commission was named, Chicago architect Daniel H. Burnham played a catalytic role by disregarding McMillan's initial instructions to produce a "preliminary" scheme, pushing instead for an ideal solution. Burnham's leadership, in turn, engendered a deep commitment among all the plan-makers, including McMillan and his political aide, Charles Moore, to the plan itself. Consequently, its creators became its chief advocates in the struggles that followed its release. Finally, the architectural profession through the AIA and a host of civic arts-advocacy groups brought together by the burgeoning City Beautiful Movement established a national constituency for the plan outside of Washington that proved crucial to its survival.

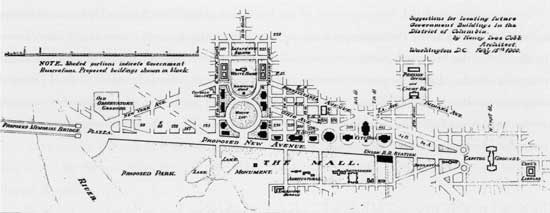

By any telling, the story begins with the effort to celebrate the centennial. The initiators were leaders of the Board of Trade, the most powerful civic promotional body in the capital. After organizing in October 1898, they approached President William McKinley in mid-November, suggesting several ideas: a memorial hall, a majestic bridge across the Potomac River, or some other durable work that would "inspire patriotism and a broader love of country." [9] These conventional, if costly, ideas typified the rituals and piecemeal methods of city-making then commonplace in the United States. When neither the House nor the Senate authorized a specific project, the Board of Trade called a meeting of local, congressional, and national centennial committees for 21 February 1900. This was to be a glittering occasion, staged as much to honor the state governors who comprised the national committee as to make major decisions. It would culminate in a lavish banquet that would feature the surprise illumination of a huge "American flag of electric lights," emblematic of the unabashed patriotism of the era. Prior to the event, the local sponsors had agreed among themselves to push the Potomac River bridge as their most popular goal. The centennial, they hoped, would climax with the laying of its cornerstone. But to everyone's surprise, the assemblage substituted entirely new objectives. [10] This turnabout was the work of Senator McMillan, a millionaire and, by reputation, "one of the five senators who 'practically run the United States.'" [11] McMillan was appointed to the Senate Centennial Committee on 16 February 1900, and five days later became chairman and spokesman of an ad hoc group to evaluate centennial projects. Instead of promoting the bridge, the favorite project of local leaders, McMillan called for the enlargement of the White House, an idea of long standing in Washington, and proposed the building of a three-mile-long Centennial Avenue to begin at the foot of Capitol Hill and to run obliquely through the Mall to the Potomac River (fig. 2). The latter idea, said the next day's Evening Star, was "a new scheme, unverified by official surveys, virtually unheralded and unknown." [12]

McMillan's sponsorship of the avenue plan signaled a critical turning point in the centennial discussions. On the surface, he had raised a genuine, if far-fetched, civic art issue being debated chiefly among Washington architects: whether the original design of the Mall should be reinstated. When McMillan publicly announced the avenue plan, he upheld it as a fulfillment of L'Enfant's dream and as an opportunity to group public buildings, a civic art issue also current among architects. [13] But he was not being candid. The avenue plan had much less to do with L'Enfant and civic art than with two major pieces of railroad legislation that he had recently introduced in the Senate in December to January, 1899 to 1900. Both bills represented complex bargains hammered out during the previous three years with the two railroads that entered the capital, the Baltimore and Potomac (B & P), which was owned by the powerful Pennsylvania Railroad, and the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (B & O), which operated a terminal at New Jersey Avenue and C Street, NW. [14] The laws committed the railroads to eliminate grade crossings by removing tracks from the city streets. This hazard, common to most American cities, had killed annually as many as three people and had yielded "a steady stream of serious accidents, one occurring roughly every three weeks." [15] The laws, in turn, authorized each railroad to build new passenger terminals. The old, crowded B & P depot on the Mall would be replaced by an enormous, up-to-date facility in the same location but on a much expanded, fourteen-acre site between Sixth and Seventh streets. The existing tracks across the Mall would be ripped up and rebuilt nearby on a massive, elevated structure to be thrown across the Mall. [16] Never before had anything so fundamentally destructive to the Mall—or to L'Enfant's vision of it—been contemplated. Yet as sponsor of the legislation, McMillan had wedded himself to the scheme for as long as the Pennsylvania Railroad refused to budge from its coveted position. Viewed in this light, the proposed avenue represented a grand approach street to the new terminal. Its curiously oblique alignment would offer travelers a direct route eastward toward Capitol Hill and westward toward the White House, making the new terminal "so . . . easy of access as if it were the very pivotal point to all else" in the city. [17] Why McMillan introduced the idea is a significant puzzle. Even the Pennsylvania Railroad opposed it. [18]

The Army Corps of Engineers within the War Department became McMillan's first and most determined antagonists. Routinely, Army engineers assigned to duty anywhere in the country reviewed federal public works and reported their findings to the president, who submitted them to Congress. As early as 29 January 1900, the Corps in Washington responded to an official request by McMillan for their technical judgment of his railroad bills. [19] They more than replied: they exploded. Colonel Theodore A. Bingham, the outspoken superintendent of the Office of Buildings and Grounds (since 1867 under the War Department), denounced the proposed terminal as a desecration of the Mall, a travesty of L'Enfant's "noble plan," and an "unpatriotic" rebuke to the memory of George Washington. [20] McMillan's diagonal avenue plan further outraged the engineers. [21] On 5 March 1900, less than two weeks after McMillan unveiled his scheme, Bingham submitted an alternative Mall plan to President McKinley. In it, he banned the proposed terminal to a position south of the Mall, called for a mid-Mall boulevard between Capitol Hill and the Washington Monument, and suggested that any new public buildings be erected along Pennsylvania Avenue. [22] Meanwhile, the avenue plan had alarmed other Washingtonians, especially businessmen who had long favored upgrading the triangle of land between the Mall and Pennsylvania Avenue. "Given up almost wholly to slumdom," with prostitution along Thirteenth and Fourteenth streets, this area disgraced respectable Washington. [23] By 1900 downtown interests clearly wanted the area upgraded by erecting new government buildings—an incremental slum-removal program. [24] But McMillan's proposed avenue and the building sites he favored along it lay far enough to the south to undercut that hope while stirring fears that Pennsylvania Avenue might become a "back street." [25] Thus, the fate of the Triangle slum and of Pennsylvania Avenue also became entangled in the battle and, ultimately, in the Senate Park Commission plan. Finally, the avenue plan impinged upon a park system initiated by the Washington Board of Trade in 1899. Following the lead of many American cities in the 1890s, the board had contemplated a great chain of parks and parkways as proof of civic stature. Washington, they claimed, already possessed magnificent resources: the newly made 739-acre Potomac Park; the National Zoological Park in the southern end of Rock Creek valley; the immense Rock Creek Park, just north of the zoo; the parklike grounds of the U.S. Soldiers Home; and various Civil War hilltop fortifications. But except for the zoo, none of these parcels had been developed yet for regular public use, let alone linked by parkways. [26] Well before McMillan had proposed his avenue plan, the Senate's District of Columbia Committee had aired these ideas and had even readied legislation authorizing a park commission to devise a scheme. [27] But McMillan's proposed avenue raised awkward questions about how such a "grand thoroughfare" could serve public needs and railroad interests simultaneously. Also under scrutiny was the free grant of Mall land to the Pennsylvania Railroad by the proposed grade crossing legislation. [28] These unresolved and conflicting goals resulted in a broad battle over the future development of the nation's capital. Senators, congressmen, army engineers, centennial promoters, downtown businessmen, Civil War veterans, the Washington press, and numerous civic leaders had joined the fray, all disputing basic questions of civic art, park system design, and even slum removal, as if these were interrelated considerations.

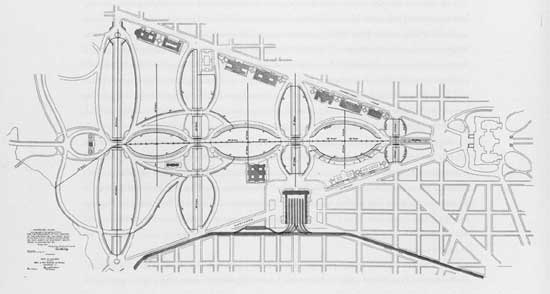

To reconcile these divergent viewpoints, McMillan, on 14 May 1900, introduced in the Senate a resolution asking the president to appoint a panel of art professionals. An architect, a landscape architect, and a sculptor would work with Army engineers to devise a plan for the entire Mall-Triangle area and also to devise a "suitable connection" between Potomac Park and the zoo. [29] The same experts would design the enlargement of the White House. In effect, McMillan sought to reinstate the architects' and artists' traditional right to oversee construction of their own works. The Army engineers had usurped this role in 1867 when Congress had relegated architects to the task of providing only the first drafts of public buildings while asking engineers to both provide technical expertise and wield executive authority over construction, including any design changes they deemed necessary. In the House version of the bill, the Army engineers, not a panel of art professionals, would carry out the work. On 6 June a House-Senate conference resolved the impasse, with the engineers maintaining the executive role they had played for the past three decades. The chief of engineers then assigned Bingham to the tasks of redesigning the White House—as the president's aide-de-camp, he had worked out of that building since 1897—and of hiring a landscape architect to plan the Mall Triangle area and the parkway link to the zoo. In October the Ladies Home Journal published Bingham's massive, if truncated, version of Frederick Dale Owen's 1890 plan for White House enlargement. [30] On 5 December the War Department issued a Mall design by Samuel Parsons Jr., the New York landscape architect chosen by Bingham (fig. 3). The Parsons plan, though idiosyncratic, fulfilled one purpose of the engineers by relegating the railroad terminal to the south of the Mall. "A lightning express," Parsons remarked, "is quite incompatible with a green garden and singing birds." [31]

The American Institute of Architects assembled in Washington for its annual convention on Centennial Day, 12 December 1900, having rescheduled its meetings to address the issues provoked by the Centennial Avenue scheme. Above all, the AIA wanted Congress to entrust the shaping of the capital core to the nation's premier architects and artists, the same aesthetic elite that had crystallized civic art aspirations in America at the Chicago World's Fair of 1893, or World's Columbian Exposition as it was formally called. Glenn Brown, the secretary of the AIA who masterminded this strategy, was well prepared professionally and politically. [32] About ten years earlier, while making an exhaustive study of the U.S. Capitol, Brown had recognized L'Enfant's Mall as the true vista to and from the Capitol. As early as 1894 he had launched a personal crusade to arouse his profession to reclaim the Mall in accord with L'Enfant's intentions. Even then, he had opposed the Army Corps of Engineers for the job, reflecting an enmity toward engineers endemic to his profession and notably virulent among AIA members. That body, Brown remarked acidly in 1894, had "never been accused of being artistic." [33] In 1887 Brown had also organized the Washington AIA chapter and in 1895 to 1897, with other chapter members, had established the Public Art League, the first organization to advocate the creation of a national fine arts commission. [34] As national secretary of the AIA, Brown served an organization already steeped in pressure-group tactics learned from its long struggle to enact and then enforce the Tarsney Act of 1893, a law that stipulated open competitions for federal buildings. [35] Alarmed by the ill-fated Centennial Avenue, he quickly persuaded the AIA to stage its annual meeting as a protest against haphazard city building in the nation's capital. [36] Brown made the "Grouping of Government Buildings, Landscape, and Statuary" the meeting's organizing theme, evoking the growing enthusiasm of his profession for ensembles of buildings utilizing classical architecture with baroque spatial effects, especially when achieved by collaborating architects, sculptors, painters, and fine craftsmen. [37] Many American architects, most especially the AIA elite, had absorbed this Renaissance ideal from studies at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. [38] In all, Beaux-Arts classicism in the United States, sometimes called the American Renaissance, conveyed a host of ideas then emergent in national culture: public order, progress; civilization, refined taste; civic pride; and national wealth and power. From March to November 1900 Brown recruited speakers for the AIA convention and orchestrated their assault, alerting them to Bingham's article in the Ladies Home Journal and even cautioning sculptor H. K. Bush-Brown against proposing any commission "dominated in any way by the army engineers." [39] When the architects assembled, they scorned Bingham's White House scheme and on 13 December staged an evening session on the design of the capital city that was reported in local papers. [40] Every AIA speaker sought a formal, monumental, aesthetically unified composition of buildings, statuary, and public grounds, all done in a grand manner and all rendered consistent with the L'Enfant plan as they understood it. "The city of to-day has grown too large to be picturesque," C. Howard Walker proclaimed. [41] No speaker that evening discussed the park system of the city or the suburban districts through which it would reach. [42] Earlier that day, however, five representatives of the AIA had met with McMillan or his aide Moore, and, almost certainly, someone from the Board of Trade. [43] The Board, long accustomed to working with McMillan, had wanted backing for its park ideas. [44] Not only had the architects denounced Bingham, but they would ignore the Bingham-commissioned Parsons plan for the Mall-Triangle at their public session on the design of the city that evening. McMillan, for his part, still had his eyes riveted on his grade-crossing legislation, especially his bill authorizing the Mall terminal. Even as they met, his opponents in the House of Representatives were preparing to cite engineering criticism and the Parsons plan as justifications for voting down McMillan's legislation. [45] McMillan wanted the architects to sanction his claim that he had the beauty of Washington at heart. The architects, in turn, satisfied the senator's needs in one critical respect: they accepted, as a matter of realism, his terminal in the Mall. [46] Once allied with McMillan, the AIA had no choice but to embrace park planning. Powerful as McMillan was in Washington affairs, his District of Columbia committee lacked authority over building location, which belonged to the Senate Committee on Public Buildings and Grounds, or over statuary, which lay with a Joint (House-Senate) Committee on the Library. [47] But McMillan did have power over park matters and had already worked with the Board of Trade to prepare park legislation. Thus the AIA agreed to address this issue, and the Board of Trade, the chief promoter of the park system, agreed to add the subjects of building and bridge placement to its publicly stated goals for the city. [48] Ostensibly, McMillan had fathered a new coalition for the physical improvement of Washington and a strategy for seizing the planning initiative from the engineers. In fulfillment of this bargain, McMillan introduced Joint Resolution No. 139 in the U.S. Senate. Intended to win the support of both houses of Congress for the planning of Washington, this measure authorized the President of the United States to appoint a commission consisting of two architects and one landscape architect to "consider the subject of the location and grouping of public buildings and monuments . . . and the development and improvement of the park system" of the district. An appropriation of $10,000 was sought for expenses. [49]

Joint Resolution No. 139 would never clear the Senate let alone the House. In the House, Joseph Cannon, the chairman of the House Appropriations Committee, already loomed as a predictable adversary, notorious for his "skinflint" proclivities and distrust of artists. [50] Nonetheless, McMillan found a way to honor his bargain. [51] After 12 February 1901, when his B & P railroad bill was finally enacted, McMillan's trusted aide and confidant, Charles Moore, suggested a new strategy (fig. 4). [52]

Accordingly, on 8 March during an executive session of the Senate held after the adjournment of Congress, McMillan obtained last minute passage of a resolution authorizing his committee to "report to the Senate plans for the development and improvement of the entire park system of the District of Columbia." Appropriate "experts" might be consulted and expenses defrayed from "the contingent fund of the Senate." [53] These experts, once appointed, would become known as the Senate Park Commission (later, often known as the McMillan Commission). But their authority, it must be emphasized, rested on a far more tenuous base than had been envisioned in Joint Resolution No. 139 back in December. Furthermore, the new measure said nothing whatsoever about public buildings and monuments. Following through on 19 March, McMillan and Senator Jacob H. Gallinger of New Hampshire, acting as a subcommittee of the Senate Committee on the District of Columbia, held an informal hearing with representatives of the AIA. Their purpose was to discuss, as McMillan put it, the "improvement of the park system" and, "incidentally," the placement of public buildings. [54] Landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. also attended, making a derailed record. [55] Everyone present agreed that three experts should be appointed, but no one articulated just what sort of plan they should formulate. As the hearing proceeded, however, a very definite objective emerged: the commission should devise a "preliminary plan" as distinct from a "matured one." [56] Because the scheme would be tentative, it could then be negotiated through the three Senate and House committees that had jurisdiction over parks, buildings, and statuary—or through a joint committee representing all three bodies. [57] A final, amended plan would be developed later. In light of the tenuous mandate McMillan had won for his commission, this cautious, consensus-building strategy made excellent sense. As Olmsted Jr. noted, McMillan wanted a "comprehensive scheme" but feared that "it might be turned down by the other Committees if it were made too complete and pushed too far." [58]

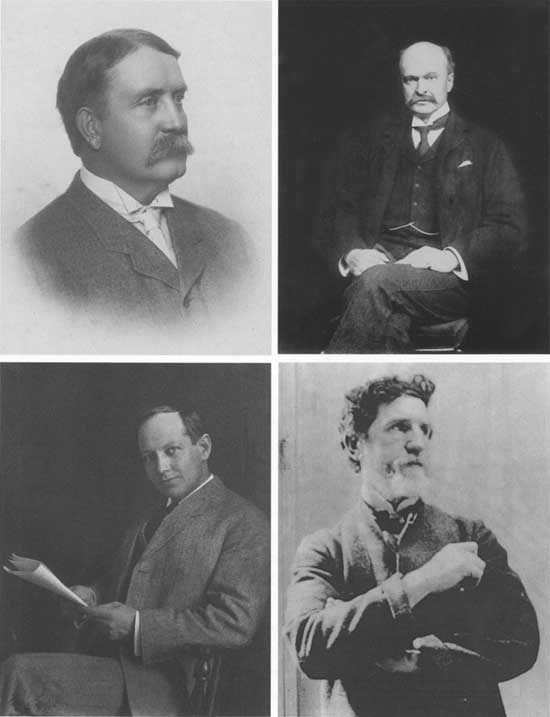

Daniel H. Burnham, the Chicago architect nationally known for having orchestrated the planning and construction of the Chicago World's Fair in 1893, played the catalytic role in redefining this mission. As Moore later recalled, he had proposed Burnham, then age 54, as a member, and McMillan, in turn, had suggested Frederick Law Olmsted Jr., then only 30, recognizing him as the mantle bearer for his eminent father. They then communicated their wishes to the AIA, which nominated them on 19 March 1901. [59] These two men, once enlisted, also took their cues from McMillan and Moore, choosing as the third member, Charles F. McKim, the celebrated New York architect who epitomized the conservative wing of the American Renaissance with its preferences for Roman and Renaissance modes of civic art over more recent and flamboyant French variants. "Only your association with the Washington work," McKim later telegramed Burnham, "made it possible for me to accept." Not until early June did Augustus Saint-Gaudens, the eminent sculptor, become the fourth commissioner, at the suggestion of McKim [60] Due to illness, he would play a limited but not insignificant role. All four men were veterans of the Chicago World's Fair; even "young Olmsted" had worked there assisting Burnham (fig. 5). [61]

At the 19 March hearing, McMillan and Gallinger made clear that they wanted a "preliminary plan" so as to avoid heavy expenses. When Burnham and Olmsted had first conferred on 22 March with McMillan, they had quickly estimated $22,600 as their "maximum expense." But McMillan wanted "between $15,000 and $20,000," [62] and he publicized a still lower sum, reported by the Washington Post as "about $10,000." [63] These dollar figures provide benchmarks for gauging how far the commission would soon exceed its instructions. From the outset, Burnham's powerful personality and expansive outlook dominated, with McMillan treating Burnham as if he were the chairman of the commission, though Burnham would later ask Moore to confirm this unstated fact. [64] Burnham declared that he would serve without compensation. The others followed suit. Burnham wanted every aspect of Washington's urban setting to be considered, just as at the Chicago Fair, when he had overseen everything from sewerage to color effects. In early May, for example, he wrote out eleven pages of topics to explore, including public grounds and buildings, a "general plan of roads" issued by the army engineers in 1898, building-height limits, and even the appearance of private lawns and gardens, public markets, and street vendors. [65] As he had explained to Olmsted in mid-April, on another matter, "My own belief is that instead of arranging for less we should plan for rather more extensive treatment than we are likely to find in any other city." [66] Action more than words defined Burnham's role. Early on McMillan informed Burnham that the new B & P terminal to be built by the Pennsylvania Railroad must be regarded as "a fixture upon the Mall." [67] But Burnham refused to accept this reality. Since September he had known that Alexander Cassatt, the president of the Pennsylvania Railroad, might employ his firm to design that very structure. [68] To Burnham this spelled opportunity, not conflict of interest. When Burnham reached Washington, 5 April, before seeing anyone and not having spoken to McKim in the interval, he "drove to the location of the Obelisk." And the next day, before making a trolley tour of the city outskirts prearranged by Moore and McMillan, the commission, led by Burnham, "drove to the Obelisk-Capitol axis." [69] Back in Chicago, on 10 April, Burnham wrote Olmsted asking if they were ready to design the Mall's main axis "on a large scale." [70] The second of two of the Commission's earliest sketch plans both dated 27 April, diagramed precisely this area, reasserting L'Enfant's Mall and relegating the railroad station to the south side of the Mall (pl. V). [71] On 20 May Burnham shifted from thought to deed. That day, he arrived at the Philadelphia headquarters of the Pennsylvania Railroad empire, hoping for the assignment to design the terminal. [72] But he did not come as a passive supplicant. He brought rough plans for the alternative site south of the Mall. Afterwards that same day in two excited letters to McKim, whom he addressed as a coconspirator, Burnham reported that Cassatt and his chief engineers had "no idea of the development we had worked out" and had still been thinking of "the old location." "The new idea," he stated with relief and some amazement, "has been received with much more open-mindedness than I had hope of." In fact, the railroad had agreed to halt land purchases "for the old scheme," at least until a more detailed proposal for "the new location" could be presented. [73] Suddenly, the "fixture upon the Mall" seemed less secure. The railroad certainly had its own reasons and interests and, in fact, had long opposed that particular site. [74] The actual direction of Cassatt's thinking soon became apparent to Burnham. On 8 June he reached Philadelphia, carrying "a hundred or more sketches for the Washington station as part of the new plan," only to discover the following day Cassatt's interest in the new terminal site granted to the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, just north of the Capitol. [75] As Burnham explained to Cassatt, writing from the commission drafting room in Washington two days later, "The frontage of the B & O plaza toward the Capitol, on which you suggested that a great union depot could be built, is 780 feet; this would be ample for a monumental treatment." [76] The commission did not know that during their trip to Europe from mid-June to mid-August 1901, McMillan would follow up Burnham's initiative by inviting Cassatt to "Eagle Head," his vacation home at Manchester-by-the Sea on the Massachusetts coast north of Boston. As Moore recalled the story off the record years later, the two men had settled the much-vexed terminal question while playing a game of golf, before Burnham's later, better-known July conference with Cassatt on the same matter in London. [77] Whatever precisely was agreed to, much remained to be done, with key negotiations still to take place between Burnham and Cassatt in late September and between Cassatt and McMillan in early December. "Mr. Burnham has accomplished a great deal in procuring this agreement from Mr. Cassatt, McMillan remarked to Moore after the late September meeting. [78] During the fall of 1901, Burnham and his chief designer Peirce Anderson concentrated on the layout and location of the terminal. Cassatt's decision to remove the proposed terminal from the Mall, even after obtaining the 12 February legislation guaranteeing the site, stemmed from many factors: McMillan's offer to persuade Congress to meet the increased expenses involved in building a tunnel under the Mall or Capitol grounds; the existence of an alternative site north of the Capitol, made available to the B & O by the newly enacted grade-crossing legislation; and a recent decision by the Pennsylvania to purchase "a controlling interest" in the B & O, which thus gave it access to the alternative site, and Cassatt's own largeness of vision. [79] But without Burnham's initiative in May, boldly suggesting the relocation of the terminal in the first place, neither Cassatt nor McMillan would have altered their course, nor would the Commission have been as zealous in pursuing "the very finest plans their minds could conceive" (fig. 6). [80]

McMillan and Moore became advisors, facilitators, and ultimately advocates. At McMillan's command a committee room in the Capitol became the commission's headquarters, and Moore commandeered the north-facing Senate Press Gallery as its drafting room manned by James G. Langdon from Olmsted Jr.'s office. [81] When Burnham, McKim, and Olmsted gathered as a team for the first time on 6 April, they traversed Washington in a luxury trolley car obtained by Moore from the president of the street railway system. [82] The following day they visited Secretary of War Elihu Root and other newly appointed members of the Grant Memorial Commission. [83] Congress had authorized $250,000—an immense sum—for a statue or memorial to Ulysses S. Grant as Commanding General of the Union Army, its location yet to be determined. [84] Root then escorted the architects to the White House to be greeted by President McKinley. [85] A reception followed at the home of Senator McMillan. All this heartened the commission. "The Washington business opens with great promise," McKim reported soon thereafter, noting the probable support of the president, Root, and Treasury secretary Lyman Gage, the latter a personal friend of Burnham. "If half of what is talked of can be carried through, it will make the Capital City one of the most beautiful centers in the world." "I do not think you will hear any more of the proposed alterations of the White House," he added. [86] Burnham returned to Chicago full of enthusiasm. "The Washington work is a stupendous job, full of the deepest interest, and it appeals to me as nothing else ever has. I have the best fellows with me, and we have the sympathy of all officials in Washington." [87] Burnham, McKim, and Olmsted all focused on the Mall, even as they began to differentiate their roles in shaping the overall plan. Olmsted, who in the 1890s had advised on street extensions and the layout of the National Zoo and St. Elizabeth's Hospital, had already favored the Mall as an open, axial corridor flanked by "masses of foliage and architecture" when he had addressed the 1900 AIA convention. [88] In contrast, neither Burnham nor McKim had had prior Washington commissions. But the thrust of the AIA convention, their shared experience at the Chicago World's Fair, as well as their own architectural and planning principles inevitably drew them to L'Enfant's plan and the antecedents of his ideas. When the commission gathered for the second time on 19 April, "Senator McMillan himself launched the enterprise by giving a large dinner at which Senators, Cabinet members, and influential citizens" met the designers informally. [89] The three men then took a three-day excursion aboard a U.S. Navy steamer down the Potomac River and up the James River to observe the remnants of southern civic design at Williamsburg and several Virginia plantations and to catch the afterglow of the late eighteenth century in America. [90] The respective roles of Burnham and McKim began to emerge, with Burnham focusing on railroad matters and McKim on the design of the Mall. The architects met again on 14 to 19 May and 10 to 11 June and took a second boat trip to the eastern shore of Maryland on 15 to 16 May to visit the Wye and Whitehall estates. [91] There is no better measure of their growing cohesion and commitment than their personal advances of about $1,000 each to George C. Curtis, the Boston model maker, to get him started on two sizable representations of the capital, one to show existing conditions, the other the proposed changes. [92] By the first week of June Burnham, McKim, and Olmsted Jr. had conceptualized the Mall as a great corridor extending from Capitol Hill west to the Potomac River—its axis realigned to bisect the Washington Monument—and crossed by a second corridor running due south from the White House (pl. VI). [93] With placement of the Grant and Lincoln memorials under consideration, McKim proposed Saint-Gaudens as a fourth member of the commission. [94] About this time, the commission also resolved the precise width of the Mall's central greensward by requesting "the Supervising Architect of the Treasury to erect some flag poles where we could see them from the steps of the Capitol and from the Washington Monument itself. . . . We tried 250 feet, and we tried 400 feet, and we tried 300 feet, and the 300-foot space was most plainly the best." [95]

When the commission, including Moore, departed for Europe on 13 June 1901 aboard the Deutschland, their goal was to refine the Mall's design and to find inspiration for its special features. Abroad, they immersed themselves in the baroque antecedents to their own thinking, mostly from the seventeenth century, with bows to ancient Rome and Haussmann's Paris. The trip had been Burnham's idea, but Olmsted had laid out the itinerary, emphasizing gardens associated with André Le Nôtre. [96] From their landing at Cherbourg, France, 19 June, until their departure from Southampton, England, 26 July, the commission visited Rome, Venice, Vienna, Budapest, Paris and environs, and London and nearby stately homes. [97] Olmsted took photographs, recording in and near Rome the Vatican gardens, Hadrian's Villa and the Villa d'Este at Tivoli, the Villa Albani, the Villa Medici, and the Villa Lante. In Paris and vicinity, they studied the Tuileries gardens, the shores of the Seine, the Luxembourg gardens, Fountainebleau, and Vaux-le-Vicomte. The last, a masterpiece of Le Nôrte, received special attention. These specific places accounted for half of the 396 photographs that survive as a legacy of the trip. [98] These pictures also reveal a preoccupation with architectonic garden details at every park, estate, and villa the travelers visited: terraces, stair systems, balustrades, statuary placement, garden vistas (fig. 7). Certain aspects of the Washington problem, it is worth noting, did not preoccupy them. At no point did they study railroad stations or their siting, although Burnham did visit the Gate d'Orsay in Paris and made a personal side trip for this purpose to Frankfurt, Germany, at the behest of Cassatt [99] Nor did they explore the issues that concerned Olmsted, vis-à-vis a city-wide park system for Washington, except to study river quays in Budapest and Paris. [100] The United States, after all, already excelled in "park-making as a national art." [101]

Recollections made years later bear out these observations. Burnham, testifying before Congress in 1904, recalled the commission studying "every notable plantation where trees were used and an open space left between them" and finding at Bushy Park and Hatfield House in England the most satisfying approximations for the Mall's width, 300 feet between the inner rows of trees. They had also examined "every notable avenue in Europe"" before settling on four rows of trees for each side of the Mall's central greensward. [102] Similarly, Olmsted recorded in 1935 that he and McKim, en route from Budapest to Paris, had decided how to lay out plantations of elms to frame the Washington Monument terrace. [103] And Moore, whose biographies of Burnham and McKim best record the trip, recollected that at the Villa Borghese, it was agreed that the proposed Memorial Bridge would be a low structure crossing the Potomac from the west end of the Mall on axis with the Robert E. Lee mansion in Arlington Cemetery. [104] On 18 July 1901, Burnham conferred with Cassatt in London, learning that he was willing to move the train depot off the Mall, provided that the government helped to meet the costs. [105] The commission returned to the United States in high spirits, each member ready to fulfill his part of the undertaking.

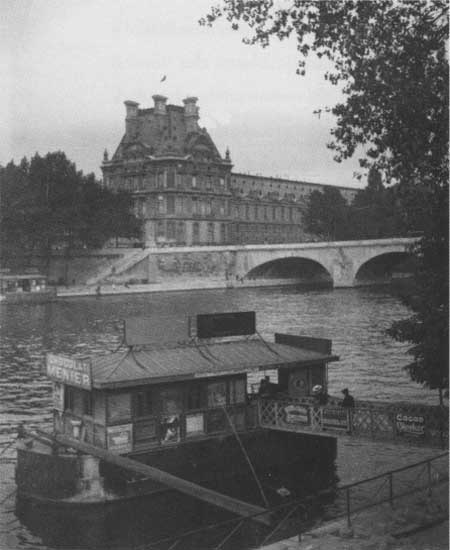

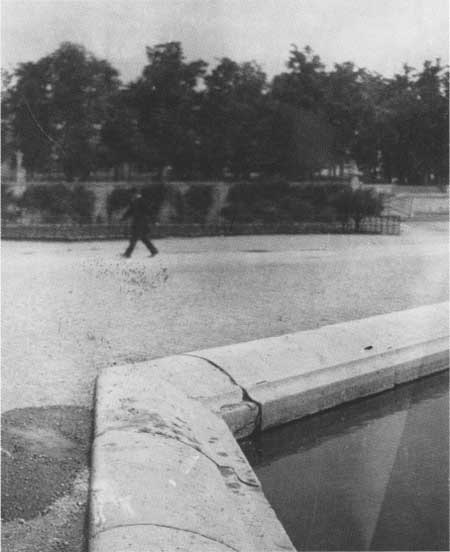

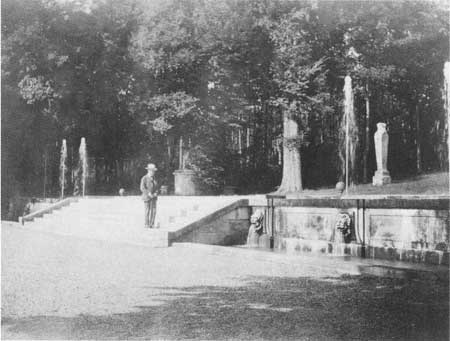

When the team disembarked at New York on 1 August Moore, by now a virtual member, immediately wrote McMillan, then at his seaside vacation home, describing the plan and, on 12 August personally briefed him for two hours. [106] "Everything is wonderfully propitious," he also reported to McKim. The Senator was "much pleased." In fact, he was already "working out in his own mind a scheme for the adjustment of the Pennsylvania railroad matter." [107] Before the commission visited McMillan at Eagle Head on 20 August, McKim recruited William T. Partridge as head draftsman. [108] Burnham, for his part, headed back to Chicago to oversee his affairs before returning to Washington on 16 August for a tour of Rock Creek Park. [109] Olmsted returned to Brookline, Massachusetts, checked up on Curtis, who was building the models in an old pool hall in nearby Roxbury, and then made his way to Washington on 11 August to confer with Langdon. [110] Since April Langdon had been assembling baseline maps and data, exploring "every foot of the District on foot or bicycle," and devising plans. And since June, he had been relaying photographs to Curtis for use in building the models. [111] On 19 August Burnham, McKim, and Olmsted reassembled for the first time since their return from Europe, inspecting Curtis' models in Boston and travelling the next day to Manchester. [112] "On the wide veranda overlooking the sea," they recounted their trip to McMillan, his wife and his daughter, several neighbors, and Senator William B. Allison of Iowa. At dinner, to impress Allison, McMillan repeatedly hailed Burnham as "General Burnham," Moore recalled years later, because a "man who could persuade President Cassatt to take the Pennsylvania Railroad out of the Mall, deserves to be a general." [113] Moore, in his memoirs, confessed that even he did not learn until long after McMillan's death that the Senator himself had played a significant role. [114] Late that evening, after the designers had departed, McMillan lavished praise on them to Allison, and McKim, hearing of this from Moore, was delighted "that the heavy weights of the Senate got so fired up." "Things are, indeed, taking a shape which no-one would have dreamed of," McKim confessed. If the commission were "allowed to perfect the scheme" and "present it in the best possible guise," he predicted, it would "arouse the interest of Congress and the public, to a degree which we can not at present realize." [115] McMillan, now wholly committed, advanced $3,000 of his personal funds in mid-September to support the cash-needy Curtis; ultimately he would loan over $12,000 to insure that the models were completed. [116] Olmsted and Langdon faced the challenge of framing a system of parks and parkways for the entire Washington area. A host of issues confronted them, including boundary realignments for Rock Creek Park, the treatment of the Georgetown waterfront, and the sanitary reclamation of the Anacostia wetlands. The most controversial was the treatment of the lower Rock Creek valley between Georgetown and Washington. The Board of Trade had been promoting an open valley park to replace the refuse-choked banks of Rock Creek as it ran about a mile through a shabby, low-income, industrial area, mostly populated by African Americans. The Army Corps of Engineers had urged filling the entire valley and running its stream through a buried sewer, a proposal favored by land developers who saw the valley as an eyesore, a health menace, and a dangerous haven for drifters and blacks. [117] As Olmsted and Langdon developed the park system for the outer areas, they drew heavily on their firm's long experience with such design, especially in park-rich Boston. Between 1855 and 1881, Back Bay had been filled in, ending noisome conditions quite similar to Washington's Anacostia flats. [118] And by 1898, Boston had begun the nation's first playground system, utilizing school-based sites, an idea Olmsted would apply to Washington. [119] Finally, the State of Massachusetts, since 1893, had undertaken a vast metropolitan system of reservations for Boston, the first of its kind in the nation, emphasizing scenic and shoreline preservation and bathing beaches, all of which Olmsted Jr. ultimately adapted to Washington. [120] On 3 December 1901 McMillan and Cassatt agreed to place the B & P railroad station on the north side of Massachusetts Avenue, a block east of North Capitol Street and facing the Capitol. [121] Although Burnham lavished attention on the station and its forecourt plaza, this complex would not be featured in the many drawings made that fall to illustrate the plan, probably because it was a private commission beyond the Senate Park Commission's mandate. But to Burnham, the "Grand Court" to be built in front of the depot as a "vestibule"" to the city was "as important as the work around the Monument in the Mall" and just as "essential to the broad scheme of improvement." [122] Burnham also initiated a very significant component of the plan quite late in the process. On 27 November he suggested grouping legislative buildings around Capitol Square and executive buildings around Lafayette Square north of the White House. [123] In addition, McKim sent Burnham a telegram on 29 November which suggests that the Chicago firm contributed to the design of the proposed Memorial Bridge. [124] Burnham also labored over the text of the Senate Park Commission's report, even hiring a Chicago writer, but Moore eventually took charge, pleasing McKim but deeply distressing Burnham who wanted a more popular style. [125] "I do not see how any of the matter that has been prepared can go into the report without being entirely rewritten," Moore confided to McKim in mid-December. "The tone of much that I have is that of flippant criticism." If published, it would "rob the Commission of the result of their very arduous and intelligent labors." [126] Olmsted matched Moore's clear, simple, and direct prose and the two produced the final draft, Olmsted writing the longer section relating to "park matters" with Moore presenting the rationale for reforming Washington's monumental core. [127] (see Appendices for Burnham's version) Well before the report appeared, in June 1902, Moore had established himself as the public voice of the Senate Park Commission, publishing "The Improvement of Washington City" in the February and March 1902 issues of the Century Magazine, the plan's first public description. [128] Paris: the Louvre and the Pont Royal. Paris: the octagonal basin in the Tuileries. One suspects that architectural details, such as this one of the pool coping, were taken by Olmsted at the request of architect Charles McKim. Vaux-le-Vicomte, the gardens. The man on the steps is Charles McKim. (Moore, Burnham, I, facing pg. 156). Rome: Villa Albani. Bagnaia: Villa Lante. Tivoli: Villa d'Este. Vienna: Donau Kanal; on quay and subway. Vienna: Restaurant in the Prater gardens. Perhaps McKim was again posing for Olmsted's camera.

As the planning unfolded, McKim steadily emerged as a key figure. From August onward, he took charge of the visual representation of the redesign of central Washington. The images soon created under his direction would win widespread support for the plan and powerfully influence the City Beautiful Movement just then emerging in the United States. Another turning point occurred in August, on the 26th, when McKim conferred with Root about the Grant Memorial, standing in for Burnham, who could not be present. Seeking support for placing the Grant Memorial at the Potomac end of the Mall, McKim discovered the depth of Root's backing and the lucidity of his advice. [129] A meeting between the representatives of the two commissions that might have been adversarial resulted in a long-term liaison. Root, a man of brilliant legal talent and cosmopolitan sensibilities, made clear to McKim that he understood the multiple issues facing the Senate Park Commission, including conflicts with Army engineers. [130] Root personally accepted placement of the Grant Memorial (previously located near the White House) at the Potomac end of the Mall. In turn, he urged the Park Commission to address the Triangle slum for the sake of local business interests who wanted to see the area upgraded and to safeguard the historic stature of Pennsylvania Avenue. McKim listened. And the plan ultimately reflected Root's advice, specifying municipal structures for this locale. Root also forcefully suggested a major publicity campaign, with a simultaneous news release about the plan in key urban centers across the nation, even naming specific cities and newspapermen. [131] And something like it was soon attempted. That fall McKim lavished attention on the Mall's details, especially the Washington Monument gardens, which one acquaintance lampooned as the "holy of holies." [132] About 13 October, the portion of the Curtis model devoted to the new Mall arrived from Boston and was installed on the sixth floor of McKim's offices. [133] Eventually, seventeen men, in addition to McKim and his chief draftsman Partridge, labored on the model and drawings, developing a notable esprit de corps. [134] "The firm complained that they never saw McKim unless they went upstairs," Partridge recalled. [135] In late November McKim relocated the Grant Memorial from the Potomac end of the Mall to the foot of Capitol Hill, probably at the suggestion of Augustus Saint-Gaudens. Although a sculptor had yet to be chosen, McKim imagined this new setting, which he called "Union Square," as Washington's analogue to Place de la Concorde in Paris (pl. X). [136] This decision, endorsed by Root but not yet by the Grant Memorial Commission, led to the shifting of the Lincoln Memorial from the south end of the White House axis (now, the Jefferson memorial site) to the Potomac site, all because Grenville Dodge, chairman of the Grant Memorial Commission, had stubbornly opposed McKim's insistence that a triumphal arch be used to honor Grant at this latter site, instead of a sculptural group as mandated by Congress and favored by Dodge. [137] That the Lincoln Memorial was decided so late underscores a fundamental aspect of the story that is easily overlooked: that the Senate Park commissioners proceeded as artists, giving precedence to design over symbolic content. From the outset, they had chosen to reinstate the original Mall from the Capitol to the Monument and to make its axis their organizing principle. By June they had elaborated a general framework, projecting the original Mall westward to the Potomac, identifying the accent points along its course, and reestablishing the White House cross axis as a central focus. By the time the team returned from Europe, if not before, McKim had settled on the principle that the Capitol axis must be terminated by a unique architectural feature. In contrast to the "arch" of the Capitol dome and the "pier" or vertical line of the Monument, the western end should be closed by a flat-topped structure, or "lintel," after the Arc de Triomphe in Paris or the Brandenburg Gate in Berlin. [138] That the architects wanted at first to honor Grant, not Lincoln, on the Potomac site startles the modern reader. In 1901, however, the placement of the Grant Memorial was a more urgent question. As these decisions unfolded, McKim also became preoccupied with the upcoming exhibit of the models, drawings, and photographs. By late August he began urging "the right kind of drawings and enough of them"—watercolor renderings—to supplement the Curtis models. [139] McMillan, asked to countenance yet another expense, replied, says Moore, "Go ahead, if the Government will not pay for it, I will." [140] Moore arranged a dinner party on 22 October for the architects to meet the trustees of the Corcoran Gallery of Art and discuss a major exhibit. [141] Eventually a dozen illustrators and architectural renderers, including Henry Bacon and Jules Guerin, produced bird's-eye perspectives and ground-level views from multiple vantage points. [142] Olmsted compiled photographs for the exhibit as well as drawings that compared parks in six major American and European cities. [143] On 15 January 1902 the Corcoran exhibit opened, with the still unfinished Curtis models in the "Hemicycle" room so that visitors might walk beside them or look down on them from a raised platform. [144] On the walls and in adjoining galleries 179 illustrations offered a compelling pictorial tour of what Washington might become, supplemented by photographs of the European settings that had inspired the commission. [145] For the heart of the city, the plan proposed a vast new ceremonial core, arranged as a kite-shaped expanse bounded by the Capitol and its building group to the east, the Lincoln memorial to the west, the White House and the executive buildings clustered about Lafayette Square to the north, and a complex of recreational buildings to the south. Immediately west of the Washington Monument where the two great axes of the plan crossed lay McKim"s elaborate sunken garden. [146] Ironically, the proposed Union Station, the key to the entire scheme, had only a shadowy presence in three overview illustrations (pls. VII, VIII, XIII). [147] For the periphery, Olmsted provided a state-of-the art park system, including a Potomac parkway link from the Mall. Less prescriptive than McKim"s monumental core, it suggested broad treatments more than detailed and completed designs. Nothing like this exhibit had ever before been mounted in the United States: a spectacular display of a new vision for an already built city, specifying the future direction its development should take on a comprehensive basis. With the whole of Washington as its object, it captured the entire trajectory of the Senate Park Commission since March 1901: what its final report would describe as "the treatment of the city as a work of civic art." [148] Visitors could attend the exhibit free of charge on Tuesdays, Thursdays, Saturdays, and Sundays or pay a twenty-five cent fee all other days. [149]

By framing an ideal scheme, the Senate Park Commission had embraced one horn of a then insolvable political dilemma. If it had followed its original instructions to produce a "preliminary plan," subject to negotiation with other Senate committees, the result, at best, would have been a politically brokered, lackluster outcome. Almost certainly, the railroad would have remained in the Mall. But opting for a perfected plan had entailed great risks, financially and politically. By mid-December 1901 the commission had already "entirely used up the contingent fund of the Senate." [150] And by September 1902, when all its expenses had been accounted for, the price of its idealism had become apparent. The Curtis models alone, originally estimated at $13,000, had cost nearly $24,500. McKim had spent over $17,000, mostly for draftsmen and illustrators; Olmsted, about $4,300 on expenses and assistants; and Burnham, $1,550. Altogether, an undertaking originally estimated by McMillan publicly at $10,000 and privately at $15,000 to 20,000, had consumed almost $55,500. [151] These excesses made the commission an easy political target, giving rise to myths of its wanton, almost dissolute ways. Repeated and embellished from year to year, they would find expression in 1904 in the Chicago Chronicle. Senator McMillan, so the story ran, had believed the cost would not exceed $5,000. But the commission had "immediately entered upon a career of extravagant expenditure that has few parallels," hiring a huge staff that occupied "nearly an entire floor of the new Willard Hotel, the most expensive in Washington," and then sailing "for Europe with a large and expensive retinue." McMillan, though a man of "sincerity and patriotism," had become "a victim of bad faith." Significantly, one fact in the tale was correct, or nearly so: that "Burnham, McKim, and Olmstead [sic] contracted obligations aggregating $60,000." [152] This reality kept the myths alive. The only escape, politically, was to avoid head-on debate over the plan as a whole. Although the commission had assuaged local advocates of a memorial bridge, of Triangle slum redevelopment, and of Civil War fort sites, it also had made enemies, beginning with Colonel Bingham and the Army Corps of Engineers and now, potentially, those who spoke for institutions already present on the Mall, especially the Botanic Garden and the Department of Agriculture. Furthermore, any adversary could count on support from the plan's most powerful opponent, Joseph G. Cannon, of Illinois, a Congressman since 1873, the chairman of the House Appropriations Committee, a leader of Old Guard Republicans, and, beginning in 1903, Speaker of the House. [153] In December 1901, well before this line-up of forces had become fully visible, Glenn Brown, working with Robert S. Peabody, president of the AIA, began to advocate a permanent art commission to enforce the plan, enlisting McKim and activating the Public Art League (PAL). With the Senate Park Commission about to complete its work, Brown feared that Congress might assign its implementation to "the Commissioner of Public Buildings, an army engineer, or may place it under . . . the Chief Engineer of the Army." [154] Significantly, the first full-dress discussion of this proposal took place in New York, then the center of public art advocacy in the United States. On 16 December, at the office of architect George B. Post, McKim, together with Richard Watson Gilder, editor of Century Magazine, and Saint-Gaudens—both of them PAL officers—and Frederick Crowninshield, president of the Fine Arts Federation of New York, decided to defer to the judgment of Senator McMillan, as conveyed by Moore in a letter sent to McKim for use at the meeting. [155] Although McMillan nine months earlier had foreseen the need for a permanent commission, the politics of the plan now looked very different. [156] Noting the poor shape of District finances and "a disposition in some quarters . . . to criticize the cost of your present plans," Moore, speaking for McMillan, thought it "unwise to give jealous and disgruntled people an opportunity at this time to say that the architects propose to run the country and shut out all others." McMillan was dealing with "500 individuals from all parts of the country"" with diverse opinions. "The only thing to do is to overcome them in an easy fashion that will leave no bad blood...." [157] In short, the backers of the plan should offer no easy targets, especially measures that might jeopardize the entire effort. When Peabody revisited the issue in mid-March 1902, Moore again delivered McMillan's verdict through McKim. "Any movement at this time to secure a permanent Commission will be bad policy.... The present situation can not be improved, and may be seriously impaired by the proposed legislation." [158] Only a gradualist approach offered an escape from the dilemma, keeping the plan alive by advancing it piecemeal. For McMillan, this meant pushing his Union Station bill, which he regarded "as the foundation of all the work." [159] Once that was settled, then he would consider a permanent commission, he told Moore in April. [160] Because the railroad in the Mall had long been recognized as a mistake, the Senator got his bill through the Senate by 15 May 1902, shortly before Congress adjourned. [161] Then, unexpectedly, Senator McMillan died, 10 August, while at his vacation home in Massachusetts. Suddenly, the political mainspring of the plan was gone. In shock and grief, Olmsted wrote to Moore from Paris, where he had been studying European zoos. "I fell at once to wondering, fearfully, how seriously his irreplaceable loss would set back the movement upon which we have all come to set our hearts," he confessed. [162] McKim and Burnham, with Moore, joined the McMillan family in Detroit. Moore, his patron now dead and his career disrupted, would return to Washington, at the family's request, to settle the Senator's affairs and to shepherd the Union Station bill through Congress, almost as a memorial. [163] On 4 December the House District Committee approved the bill; on 28 February 1903, Congress enacted it. [164] By 16 March Moore had left the capital for new employment in the far northern reaches of Michigan, at Sault Sainte Marie. [165] With his departure, the plan stood exposed to its enemies as never before. New political tactics would be needed if anything more than a new railroad station was to be its outcome.

To its good fortune, the Senate Park Commission plan coincided with the emergence of the City Beautiful Movement in the United States, quickly becoming one of its icons. Absent this development, the new vision of the Mall set forth in 1902 might never have been carried out. As a cause, the City Beautiful championed town and city beauty, drawing its support from the same native-born, business and professional groups that had been energizing municipal reform in efforts in the Northeast, Midwest, South, and West Coast since the mid-1890s. What had begun with local calls for efficient and honest governance in opposition toward bosses and venal business interests, had blossomed by 1900 into a multifaceted campaign to address the city itself as the critical arena of national life. To many reformers, the forces then wrenching the nation and its cities—immigration, industrialization, ever-larger transit and railroad empires, big business mergers, and transformative technologies, such as electricity—necessitated the fashioning of a new civic order, to be achieved through a revitalized sense of citizenship or what many called a new civic consciousness. The City Beautiful, as one expression of this ethos, became something of a crusade as the twentieth century opened. [166] As a movement, the City Beautiful wove together many threads of American aesthetic culture. The oldest of these, "village improvement," dated back to the mid-nineteenth century ideas of Andrew Jackson Downing about the upgrading of often bleak country towns and villages. By 1900, as "civic improvement," it had spread across the nation. Its activists, often women, demanded clean streets, tidy waterfronts, garbage incineration, municipal flower beds, public libraries, street trees, indeed almost anything that would make an ordinary place more visibly appealing. [167] A second thread involved "outdoor art," namely the naturalistic values that had been pushed forward by the movement for scenic urban parks, beginning with Central Park in New York before the Civil War and, after the war, exemplified by the city park system idea in Buffalo and Chicago by the late 1860s, in Boston and Minneapolis by the 1880s, and in Kansas City and Louisville by the 1890s, and culminating with the vast metropolitan system of Boston begun in the 1890s [168] A more recent and more cosmopolitan thread, then called municipal art, had emerged among the New York artists and architects who had helped design and execute the Chicago World's Fair. The Chicago spectacle, they hoped, just might persuade city officials to make greater use of murals, statuary, artistic street fixtures, and other embellishments in public places. More profoundly, they sought to turn the post-Civil War pursuit of art and culture, which had long been the preserve of the rich and wealthy, toward the adornment of the public realm. From their vantage, the Chicago World's Fair had represented a breakthrough for public art, with its great Court-of-Honor basin, framed by white, classic buildings and adorned throughout with lavish outdoor sculptural and mural displays (fig. 8). [169] After the fair, a devastating economic depression had thwarted the impulse to translate this model into the fabric of real cities until the return of prosperity, about 1897.