Resorts operating before the turn of the century included Tremont and the Mineral Springs Spa and Racetrack, the latter located near the present Worthington Steel plant. South of the lakeshore, G. W. Merrill’s place at Flint Lake in Valparaiso was a popular fishing and swimming spot in the 1880s. In 1893, W. H. Leman reportedly built one of the duneland’s first summer cottages near Lake Michigan and the present day Mineral Springs Road. After 1900, Porter Beach drew crowds to dances and an ice cream concession. From Miller to Michigan City, from the west to the east ends of the duneland, fun seekers found diversions ranging from ferryboat excursions to boardwalk dances. Recreational businesses in turn spurred residential development that capitalized on the resort opportunities of the duneland as a sales tool.

www.monon.monon.org In 1889, the cry arose for public recreational development in Michigan City. Proponents of public lakefront access wrote to Michigan City Mayor M. T. Krueger to obtain construction of a swing bridge at Franklin Street. The proposed bridge would open the Michigan City lakeshore to the public and enable "fine summer hotels and drives along the beach." Opponents of public recreation decried the proposal as an obstruction to recreation and a tax burden.

mclib.org The development of Washington Park and the Michigan City harbor heightened commercial interest in Michigan City's lakefront—a pattern later repeated around Indiana Dunes State Park and Indiana Dunes National Park. Just east of Washington Park, Sheridan Beach became one of the first residential developments in the Indiana Dunes around the turn of the century. According to Michigan City historian Gladys Bull Nicewarner, the Welnetz family built the first summer cottage on Sheridan Beach in the early 1900s. The Welnetz's wooden cottage provided a prototype for other Sheridan Beach summer residences, with a lakeside covered porch and a second story dormer. A few years later, the Sheridan Beach Land Company platted Sheridan Beach Drive and other streets for a new residential subdivision. The land company’s first speculative resort cottage, called Pioneer, was a stained shingle building, the first to be located on Sheridan Beach Drive. Nicewarner points out that initial sales for Sheridan Beach property were slow “because people in Michigan City could not yet see the sense of building summer homes on what, to them, seemed like a wasteland of worthless sand.” However, a 1908 postcard depicts a cluster of cottages with broad gabled roofs standing on pilings at Sheridan Beach. The postcard was published by George Leusch, who sold souvenirs and ice cream from his store at the northwest corner of Franklin and Michigan Streets in Michigan City. Leusch promoted Michigan City with dozens of pictures of the lakefront reproduced on postcards, plates, match holders, and other items. Promoters such as Leusch popularized the Indiana Dunes as a recreational destination and a possible summer cottage location for people in the Chicago metropolitan area. To the west, the present Porter Beach area also experienced development near the turn of the century. In 1891, the current Porter Beach site became the Lake Shore Addition to the New Stock Yards as Chicagoan Orville J. Hogue recorded a plat in the Porter County courthouse showing hundreds of twenty-five by one hundred foot lots. Streets with Chicago names surrounded these lots: State, Dearborn, Clark, and Michigan. Local researchers maintain that Chicago realtors tricked buyers into thinking they were buying land near the Chicago stockyards, not inaccessible property platted over Porter County sand dunes.

Others eyed the Porter Beach lakefront as a perfect entertainment spot. Although residential development proved slow, recreational attractions drew visitors to Porter Beach almost a century ago. "Porter Beach is now the center of gravity which is attracting the crowds from this part of Porter County," the Chesterton Tribune noted in 1904. “Every evening hundreds of people from as far south as Morgan Township gather at the beach, and have a good time bathing in the cool waters of Lake Michigan.” However, the article bemoaned the lack of commercial facilities for beachgoers: "If some one would only put up sheds for horses, and a house for shelter for people at the beach, and serve something to eat, and provide some kind of amusement for the crowds, there would be money in it." Nine days later, an entrepreneur named Charley Swanson heeded the Chesterton Tribune’s call for commercial recreation on the beach. Swanson announced in the newspaper that he would serve ice cream Saturday and Sunday nights at Porter Beach. He invited "all who desire to get cool and keep cool to come." Around 1912, Elmer and William Johnson, two local fishermen, opened a rustic fish house at Johnson's Beach, east of Porter Beach near the present site of the Indiana Dunes State Park parking lot. The brothers later expanded their business, opening a restaurant serving popular fish and chicken dinners and offering bathing facilities. According to the Gary Post-Tribune, by 1907 seven cottages existed at the Miller lakeshore. In 1911 Drusilla Carr, who owned beach land east of the steel mills, invited visitors to her beach by opening a bathhouse. "The invasion of pleasure seekers began immediately," reported the newspaper. By 1917, Carr’s Beach included a boardwalk, dancehall, shooting gallery, roller rink, and about one hundred cottages for which people paid one hundred dollars yearly rent. A 1917 photograph from the Calumet Regional archives shows throngs of people, many in bathing suits, some in straw hats, dancing on a wooden platform at Carr's Beach. Thus, entrepreneurs such as Carr and the Johnson brothers opened the door for further development of weekend and summer cottages in the dunes. Before 1920, tents, summer cottages, cabin rentals at places like Carr’s Beach, and rooms in private homes comprised the bulk of duneland vacation accommodations. Most hotels were in cities, catering to railroad travelers, traveling salesmen, and other business people. During the 1910s, prominent local hotels included the Hotel Gary at Sixth Avenue and Broadway in Gary and the Queen Anne style Hotel Vreeland at 218-220 Franklin Street in Michigan City. Michigan City businessman O. S. Glidden built one of the earliest beach resorts in the duneland during the 1910s. To attract tourists to the beach and, he hoped, to encourage them to invest in beach property, Glidden located the Shamut Hotel (no longer extant) on the side of a dune, overlooking the lake in Sheridan Beach. Three primary factors spawned these early duneland recreational facilities: increased leisure time, larger salaries, and improved transportation from Chicago to the Indiana Dunes. Labor organizations had succeeded in obtaining shorter workdays: by the 1880s the normal workday was ten hours for many industries, down from the eleven hours or more per day that was standard in 1830. Increased disposable income also encouraged leisure pursuits. Despite unreliable statistics on working class income, many historians agree that real wages rose in the second half of the nineteenth century. According to historian Clarence Long, both daily and annual earnings increased about fifty percent between 1860 and 1890.

The availability of cheap transportation from Chicago to Northwest Indiana greatly enhanced people's inclination to travel to the Indiana Dunes. By 1917, duneland tourists enjoyed a few transportation options. In The Sand Dunes of Indiana, E. Stillman Bailey noted the accessibility of the Indiana Dunes to Chicago. In 1917, four railroads ran daily trains from Chicago east to duneland stations: the Lake Shore and Michigan Southern Railroad; the Michigan Central Railroad; the Baltimore and Ohio; and the Pennsylvania. The interurban electric Chicago South Shore and South Bend Railway Company (South Shore Line) operated twenty-two daily trains between Chicago and South Bend, Indiana. Riders could disembark at seven Indiana Dunes stops between Miller and Michigan City. Motorists could also drive to the dunes on a circuitous thirty-six mile route from South Chicago to Miller. With time, disposable income, and convenient transportation, some of Chicago’s middle class and working class turned toward the Indiana Dunes for rest and relaxation. Many duneland residents recount stories of summer trips from Chicago to duneland beaches. Betty Davin, for example, remembers that as a child in the 1920s she took a streetcar from Hyde Park to Ninety-Fifth Street on Chicago's South Side. Then she caught a New York Central train to Miller and rode a "Mack" bus down Lake Street to the beach, where her grandmother had a cottage at 9031 Lake Shore Drive. In 1922, Davin's grandmother and her two sisters built their own cottage with materials carried down the beach by a horse pulling a raft in shallow water. “When I was a little girl, we'd stay at the cottage all summer and take the train back to Chicago on weekends to meet my father who was a traveling salesman,” Davin wrote in a 1998 issue of Steel Shavings.

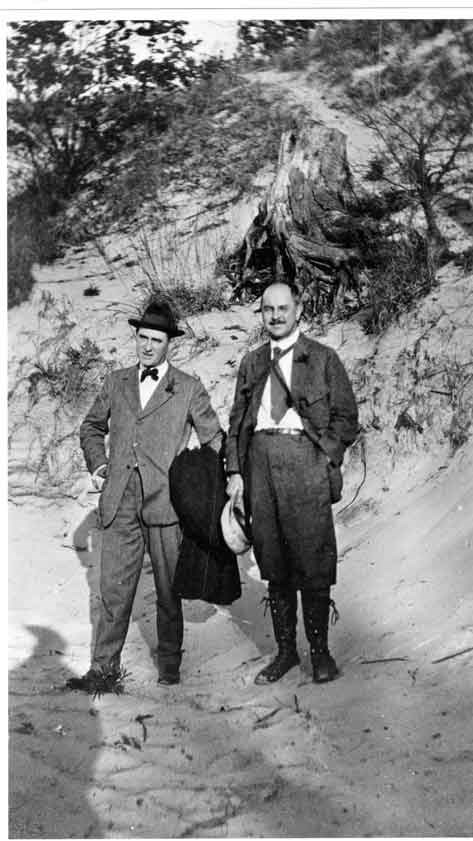

Many people had their first taste of the duneland during trips organized by outdoor recreation groups. Advocates of fresh air and hearty exercise aimed to lure urbanites from dance halls and other diversions they feared could disrupt the social order. In 1904, one such group, the Chicago Playground Association, formed by Jens Jensen to provide outdoor recreation for urban children. The association viewed hikes to areas such as the duneland as a way to expose city children and settlement house workers to nature's regenerative powers. One of the first adventures of the association's Saturday Afternoon Walking Trips was a 1908 Memorial Day hike to the Indiana Dunes. A crowd of 338 attended the event. By 1911 the group had sponsored about eighty-six afternoon walks and twelve all day hikes. The Indiana Dunes proved to be one of the group's most popular destinations. It was a site almost untouched by urbanization yet only a short train ride from Chicago These early recreational enthusiasts, including prominent Chicago scientist Henry Cowles and sculptor Lorado Taft, formed another more broadly based organization, the Prairie Club of Illinois. Incorporated in 1911, the Prairie Club soon became the most influential promoter of the Indiana Dunes as a recreational destination. Whether hiking along the beach or tobogganing down Mt. Tom, Prairie Club members learned to savor the outdoor life. A 1929 Christian Science Monitor article noted that Prairie Club members devised their own outdoor costumes for hitting duneland trails. As they learned to play in the dunes, they shed cumbersome Victorian era clothes for knickers, puttees, waterproof boots, hiking breeches, and rough coats.

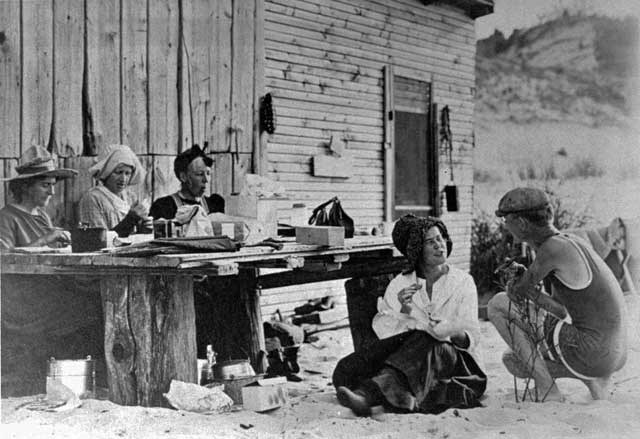

Prairie Club members publicized the wonders of the dunes through their Prairie Club Bulletin, published in Chicago, and received coverage of their activities in Chicago daily newspapers. The bulletin listed a complete schedule of South Shore Line and Lake Shore and Michigan Southern Railroad trains to the Indiana Dunes. It also offered directions to the Prairie Club camp "north from the Tremont station of the South Shore Electric Railroad less than a mile over a country road and then three-quarters of a mile over a pretty, well-marked trail through the woods." To entice visitors to the dunes, the bulletin noted the duneland's rich variety of birds, trees, flowers, and landscapes. The bulletin also described "interesting tramps," including the backbone of the ridge to Mount Tom, Tamarack Swamp, Dune Park, Mineral Springs, the Furnessville Blow-Out, and the Sky-Line Trail to Michigan City. Although members staunchly supported conservation of the Indiana Dunes, the Prairie Club sparked some of the residential development there, especially in the Tremont and Waverly Beach vicinities. In 1913, Prairie Club members raised money to build their beach house atop a fifty foot sand dune on land they leased. The structure was located approximately where the Indiana Dunes State Park water tower now stands. The Prairie Club beach house featured a broad gabled roof, screened sleeping porches, kitchen facilities with cooking utensils and tableware, and lockers for stowing gear. Active members could stay at the beach house for one week for a one dollar fee. Sleeping cots could be rented for fifteen cents per night or fifty cents per week. Initially, Prairie Club members desiring private accommodations could only pitch tents near the beach house. Photos from the Prairie Club archives circa 1915 show rows of tents stretching across Waverly Beach as far as the camera's lens could capture. Each weekend, some Prairie Club members scavenged odds and ends of lakefront debris to construct primitive accommodations near the beach house. Boards, barrels, boxes, and crates washed onto the shore served as tables, chairs, benches, and pantries for tent houses. Iron grates became cook stoves on which to grill steaks or percolate coffee. Some Prairie Club members tried to revive Native American customs by placing decorated totem poles at tent entrances. Others craved the comforts of home: “Some of the more spacious and pretentious tents had wood floors, a separate tent for cooking, a dining tent or canopied affair with open sides from which hung mosquito netting,” the authors of Outdoors With the Prairie Club commented."

In 1922, Prairie Club members purchased the sixteen acre tract on which the beach house stood as well as an adjoining thirty acres for about $29,000 or $600 per acre. To finance the purchase, the club issued bonds to its members and rented campsites for $25 annually. Members eventually built 103 summer cottages on campsites near the club's beach house. This arrangement typified the pattern of early Indiana Dunes recreational development: landowners rented small parcels of land to summer and weekend beachcombers who built cottages on the parcels. During the 1910s and early 1920s, people built simple wooden cottages along the lakefront to provide inexpensive accommodations for their summer vacations in the dunes. A circa 1920 photograph shows a colony of Waverly Beach cottages perched in the sand hills, which look like mountains. Most appear to be one story wooden cottages on piles, with pitched or hipped shingle roofs. Local historian Howard Johnson remembers the barracks-like summer cottages strewn along the Indiana Dunes in the 1910s. According to Johnson, few cottages began as permanent structures: "They were crude, with screens over openings. Originally there were no finished walls. You could see the outside walls from the inside." Pumps generated water; outdoor sinks and outhouses were common. Over time people added insulation and windows. Johnson’s family built their own dunes cottage to enjoy Lake Michigan' s healthful breezes. Around 1911, Charles and Wilhelmina Bradley, Johnson’s maternal grandparents, constructed a rough wooden cottage on the beach near the present site of the state park pavilion. Bradley leased the property for the three room cottage from a Chicago real estate company. Johnson’s family thought living on the lakefront would benefit his uncle, Robert Bradley, who suffered from tuberculosis. So that Robert could more easily breathe the summer air, his father built a sleeping bunk on the cottage exterior. Shutters slid over the bunk in case of inclement weather.

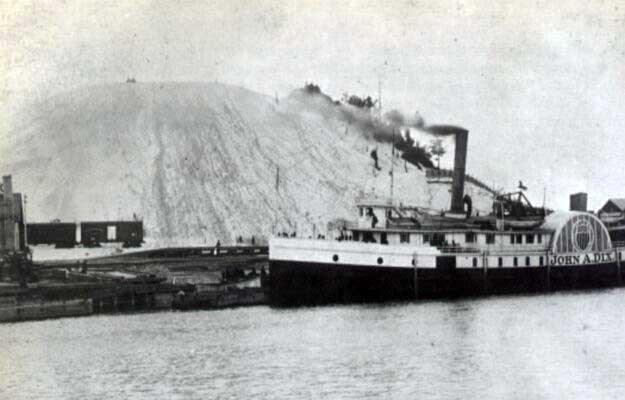

About 1913, the Prairie Club established a conservation committee, which spearheaded the campaign for a "Sand Dunes National Park." The battle for the national park stemmed from fears that industries were destroying the duneland. Numerous sand mining companies had been siphoning Indiana Dunes beaches since the late nineteenth century. Historian Powell Moore wrote that in 1898 more than three hundred cars of sand were shipped from Dune Park (present site of Midwest Steel) every day. Furthermore, steel companies such as Inland Steel bought large chunks of duneland after the turn of the century. Stephen Mather, a member of the Prairie Club conservation committee and Chicago Geographic Society, began fighting to save the dunes soon after he procured the 1916 passage of the National Park Service Act. The first director of the National Park Service, Mather held public hearings on behalf of an Indiana Dunes National Park in Chicago on October 30, 1916. He recommended that the federal government purchase an area about twenty-five miles long by one mile deep between Gary and Michigan City, Indiana. To spotlight the dunes cause, Mather published, largely at his own expense, the hearings for the national park. Spurred by Mather's initiative, a National Dunes Park Association formed in 1917 to generate as much publicity as possible for the Indiana Dunes. Composed of Prairie Club members and other conservation groups, the National Dunes Park Association alerted the public to the natural treasures of the Indiana Dunes. The association's public relations campaign brought important media attention to the Indiana Dunes. For example, a 1919 National Geographic Magazine article promoted "Indiana's Unrivaled Sand Dunes: A National Park Opportunity." Photographs accompanying the article showcased the recreational as well as the natural attractions of the Indiana Dunes, including hiking and tobogganing.

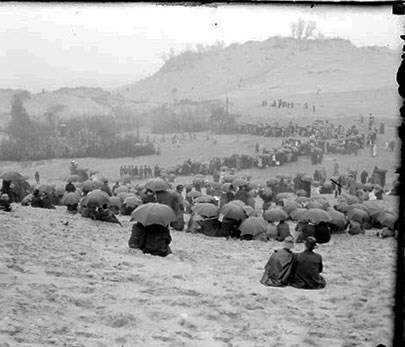

Northwest Indiana Genealogical Society Weekend and summer vacationers flocked to the Indiana Dunes as local and Chicago newspapers publicized adventures there. From 1913 to 1917, dunes aficionados mounted plays, dances, and pageants in the blowouts between the sand hills. These performances painted the dunes as a primitive environment worthy of preservation because it captured a sense of the wild that was lost in modern civilization. The pageants attracted increasingly larger crowds, topped by the estimated twenty-five to forty thousand guests who attended a 1917 performance dedicated to duneland preservation. The event received widespread coverage in Chicago newspapers. To bolster the case for national park status, guidebooks touted the area's scenic wonders and recreational opportunities. In 1917, at the height of the national park crusade, A. C. McClurg Company published Bailey's The Sand Dunes of Indiana, a 165 page natural history guide profusely illustrated with dunes landscape photographs. Bailey's vivid prose described the dunes as an idyllic environment in which one could commune with nature. The prestigious Rand McNally travel company, publishers of the country's first road atlases, also promoted duneland recreational attractions. In 1920 Rand McNally published a map of the Indiana Dunes, including the locations of steam and electric railroad routes, houses, foot trails, first class roads, and second class roads. References Weston A. Goodspeed and Charles Blanchard, Counties of Porter and Lake, Indiana (Chicago: F. A. Battey & Co., 1882), 45; George Brennan, The Wonders of the Dunes (Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill Company, 1923), 145; Chesterton Post Tribune, 22 July 1904. Gladys Bull Nicewarner, Michigan City, Indiana: The Life of a Town (Michigan City: Gladys Bull Nicewarner, 1980), 271. Ibid., 270-271; Michigan City Clerk Records E: 142. Nicewarner, Michigan City, 283. Nicewarner, Michigan City, 283; Historic Photo Files, Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore. Hardesty, Illustrated Atlas of Porter County; Michigan City News-Dispatch, 15 December 1979. Chesterton Tribune, 22 July 1904; Chesterton Tribune, July 29, 1904; Howard Johnson, interview by Janice Slupski, 24 September 1996. Gary Post-Tribune, 9 July 1925. King's Official Route Guide, circa 1912, local history files, Histories Office, Indiana Dune National Lakeshore; Nicewarner, Michigan City, 281. Roy Rosenzweig, Eight Hours For What We Will, Workers & Leisure In An Industrial City, 1870-1920 (Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, 1983), 46-49. E. Stillman Bailey, The Sand Dunes of Indiana, The Story of an American Wonderland Told by Camera and Pen (Chicago: A. C. McCLurg & Co., 1917), 142?146. Betty Davin in "Tales of Lake Michigan and the Northwest Indiana Dunelands," Steel Shavings 28 (1998): 119-120. Emma Doeserich, Mary Sherburne, Anna B. Wey, Outdoors With The Prairie Club (Chicago: Paquin Publishers, 1941), 26. A puttee is a strip of cloth wound around the lower leg, or a leather gaiter, to protect the leg from knee to ankle. Westchester Public Library, "Chronological History of the Prairie Club: The Early Years, 1898-1933," n.d.; Christian Science Monitor, 12 January 1929. “A Beach House and Dune Camp Bulletin,” Bulletin No. 54, Supplement A, The Prairie Club, Chicago, May 1916, in Prairie Club Archives, Westchester Public Library, Chesterton, Indiana. Ibid.; Doeserich, Sherburne, and Wey, Outdoors with the Prairie Club, 89-90. Ibid.; Photograph of Waverly Beach, circa 1915, Prairie Club Archives, Westchester Public Library. Doeserich, Sherburne, Way, Outdoors with the Prairie Club, 89-98. Ibid., 95; Fred Carr, interview by Janice Slupski, 15 September 1996. Howard Johnson, interview by Janice Slupski, 24 October 1996. Howard Johnson, interview by Janice Slupski, 24 September 1996; Photograph from Howard Johnson private collection, circa 1915. Powell A. Moore, The Calumet Region, Indiana's Last Frontier (Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Bureau, 1959), 131. J. Ronald Engel, Sacred Sands: The Struggle for Community in the Indiana Dunes (Middletown, Conn.: Wesleyan University Press, 1982), 17-18. Orpheus M. Schantz, “Indiana's Unrivaled Sand Dunes: A National Park Opportunity,” National Geographic Magazine 35 (1919): 430; Memo from Margery Sewell, associate editor of Fashion Art to Catherine Mitchell, Dunes Park Association, 2 February 1921, S2112, Folder 2, Indiana State Library.

|

Last updated: October 11, 2023