Last updated: August 2, 2024

Person

Stephen Tyng Mather

Library of Congress, Harris & Ewing photograph collection

His vigorous efforts to build public and political support for the parks helped persuade Congress to create the National Park Service in 1916. Appointed the first NPS director in May 1917, he continued to promote park access, development, and use and contributed generously to the parks from his personal fortune. During his tenure the service's domain expanded eastward with the addition of Shenandoah, Great Smoky Mountains, and Mammoth Cave national parks. Periodically disabled by manic-depression, Mather left office in January 1929 after suffering a stroke and died a year later.

Stephen Tyng Mather led a full active life of 63 years, from 1867 to 1930. The years spanning the turn of the century saw vast changes in the country's demographics, as well as the development of modern forms of transportation and communication, and increased leisure time. Mather was able to capitalize on these trends in his marketing efforts at the Thorkildsen-Mather Borax Company, which made him a millionaire, and in his public life as the first director of the National Park Service. During his life, Mather was an active member of numerous organizations, including his college fraternity Sigma Chi, the Sun Alumni Association, the Chicago City Club and Municipal Voter's League, and the Sierra Club. He was always a strong supporter of the University of California at Berkeley. Mather was physically active, pursuing hiking and mountaineering, often squeezed into a frenzied travel schedule related to his business and the parks. His work, travel, and tremendous physical energy exacted a heavy toll and contributed to his untimely death.

Mather recognized magnificent scenery as the primary criterion for establishment of national parks. He was very careful to evaluate choices for parks, wishing the parks to stand as a collection of unique monuments. He felt those areas which were duplicates might best be managed by others. Within the framework of "scenery," his preservation ethic covered such issues as the locations of park developments, provision of vistas along roadways, and the perpetuation of the natural scene. Mather always wished to have the parks supported by avid users, who would then communicate their support to their elected representatives. His grasp of a grassroots support system encouraged the rise of "nature study" and modern interpretation, as well as other park services, and was followed by increases in NPS appropriations. Mather was the first park professional to clearly articulate the policy which allowed the establishment of park concessioners to provide basic visitor comforts and services in the then undeveloped parks. His provision of creature comforts connected with park developments encouraged a curious and supportive public to visit the national parks.

His life is well summarized — on a series of bronze markers which were posthumously cast in his honor and distributed through many parks:

"He laid the foundation of the National Park Service, defining and establishing the policies under which its areas shall be developed and conserved, unimpaired for future generations. There will never come an end to the good he has done . . ."

Proposed "Sand Dunes National Park"

Stephen Tyng Mather left Chicago in 1915 to serve as an assistant to his friend, Franklin K. Lane, President Woodrow Wilson's Secretary of the Interior. Mather, a wealthy Chicago borax manufacturer imbued with a deep appreciation of the environment, went to Washington to manage the neglected national parks. On August 25, 1916, President Wilson signed the National Park Service Act, and Lane later appointed Mather the first director of the new bureau. As a member of two organizations promoting a Sand Dunes National Park (including the Prairie Club of Chicago,) Mather found himself in an ideal position to promote just such an entity to benefit his native Chicago and the Midwest. Within two weeks of the National Park Service Act, Mather met with Senator Taggart to draft a resolution authorizing an investigation of the "advisability of the securing, by purchase or otherwise, all that portion of the counties of Lake, Laporte, and Porter, in the State of Indiana, bordering upon Lake Michigan, and commonly known as the 'Sand dunes,' with a view that such lands be created a national park." While Congress made no appropriation for the study, local preservation groups assumed Mather's expenses, including a one-week trip to the dunes, Chicago, and Michigan City.

Mather held hearings on October 30 to gauge local sentiment on the proposed national park. Meeting in a courtroom in the Chicago Federal Building, 400 people attended and forty-two spoke in favor of the park to "save the dunes." There were no opponents. Individuals testifying were Henry C. Cowles, University of Chicago botanist; Jens Jensen, conservatioist and landscape architect; Earl H. Reed, artist and writer; Otis Caldwell, Chicago Historical Society president; Lorado Taft, sculptor (and future father-in-law of U.S. Senator Paul H. Douglas); T. C. Chamberlain, University of Chicago geologist; and Julius Rosenwald, founder of Sears, Roebuck, and Company. Some other organizations represented were the Prairie Club, Indiana Academy of Science, Chicago Association of Commerce, and the Illinois Audubon Society.

The most convincing testimony was that of Henry Cowles. The botanist had dedicated twenty years of his life to the Indiana Dunes and still took his students there for intensive academic study. The dunes were known throughout the world for their ecological importance. Cowles related the story of a group of European scientists with only two months in the United States who compiled a list of places to spend their time: the Grand Canyon, Yosemite, Yellowstone, and the dunelands of southern Lake Michigan.

Mather's assistant, Horace M. Albright, accompanied him to the dunes and compiled the National Park Service's report to Congress, which was submitted to Secretary Lane on December 20. The document represented a potential turning point for Federal land acquisition policy for the Park Service director proposed the government purchase the land for a national park from private interests, a practice hitherto verboten by Congress. He cited the example of the $50,000 appropriation to buy a tract in Sequoia National Park which was insufficient to meet the $70,000 price tag, the deficit amount coming from the National Geographic Society. Mather identified a strip of lakeshore twenty-five miles long and one mile wide for acquisition. This represented 9,000 to 13,000 acres at a price of $1.8 to $2.6 million. The park should be "contiguous and dignified," with no isolated tracts outstanding, Mather believed.

Image caption: Members of the Prairie Club of Chicago engage in a popular weekend activity in the nearly dunelands of Indiana. This particular "dunes walk" took place in 1913 in the vicinity of Mount Baldy. (Photographer A.E. Ormes, July 4, 1913, Photographic Archives, Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore)

Federal developments in the Sand Dunes National Park would be scant. Four or five roads connecting the lakeshore with the state highway would take motorists to the lake. A road along the shore itself was also a possibility, but development was not pressing because of the convenient rail lines traversing the dunes. As for Park Service administration, a superintendent and two permanent rangers were all the personnel needed for visitor protection and interpretation with additional seasonal help during the summer. Estimated cost for the manpower would not exceed $15,000 a year.

Mather declared that the Indiana Dunes were unmatched anywhere in the United States, if not the world. The area was convenient to five million people in the Chicago metropolitan area as well as millions of other Americans in the center of the nation. The principal segment of the proposed national park stretched from Miller to Michigan City, the northeast corner of Lake County to Porter County. Mather wrote:

The beauty of the trees and other plant life in their autumn garb, as I saw them recently, was beyond description.

Here is a stretch of unoccupied beach 25 miles in length, a broad, clean, safe beach, which in the summer months would furnish splendid bathing facilities for thousands of people at the same instant. Fishing in Lake Michigan directly north of the dunes is said to be exceptionally good. There are hundreds of good camp sites on the beach and back in the dunes.

Mather discounted the value of land near Gary for the park either because the dunes were less spectacular or the land was too near industrial areas. Mather discussed the unique values for which Yellowstone, Yosemite, Crater Lake, Sequoia, Mount Rainier, Glacier, Rocky Mountain, Mesa Verde, and Grand Canyon (at the time pending) merited national park status. The Sand Dunes of Indiana, Mather believed, deserved the same designation:

The sand dunes are admittedly wonderful, and they are inherently distinctive because they best illustrate the action of the wind on the sand accumulated from a great body of water. No national park or other Federal reservation offers this phenomenon for the pleasure and edification of the people, and no national park is as accessible. Furthermore, the dunes offer to the visitor extraordinary scenery, a large variety of plant life, magnificent bathing beaches, and splendid opportunities to camp and live in the wild country close to nature.

If the dunes of this region were mediocre and of little scenic or scientific interest, they would have no national character and could not be regarded as more than a State or municipal park possibility. My judgment is clear, however, that their characteristics entitle the major portion of their area to consideration as a national park project.

Image caption: National Park Service Director Stephen T. Mather (far left foreground) is accompanied by Col. Richard Lieber on an October 31, 1916, inspection tour—the day following a Department of the Interior hearing in Chicago on a proposed Sand Dunes National Park. In the center of the group in the background are Associate Director Horace Albright and his wife, Grace. (Photographer Unknown, October 31, 1916, Photographic Archives, Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore)

Because opponents were not present at the Mather hearing does not mean there was no serious opposition to the park proposal. The center of this opposition was in Porter County, Indiana. Led by the press, business and political leaders, and the Valparaiso Chamber of Commerce, the critics attacked the immense area under consideration and charged it would undermine the tax base of the region and permanently close the lakeshore to industry. Many believed U.S. Steel Corporation was the power behind the park movement because it wished to keep its competitors out.

"First Save the Country, Then Save the Dunes," 1917-1919

On December 20, 1916, Mather submitted his report to Secretary Lane who approved the report and forwarded it to Congress in early 1917. To help promote the park cause, Stephen Mather used his own money to publish and distribute the report. Thereafter, the outlook appeared bleak. Senator Taggart, the champion of the dunes in Congress, left office following his electoral defeat. Another vocal champion, Stephen T. Mather, was silenced when he suffered a nervous breakdown in the spring of 1917 and could not lobby for the park. The crippling blow came on April 6 when national priorities inexorably changed as the United States entered World War I. With revenues targeted for the national defense, any Congressional expenditure for the establishment of a Sand Dunes National Park appeared doomed. The popular slogan "Save the Dunes!" became "First Save the Country, Then Save the Dunes!"

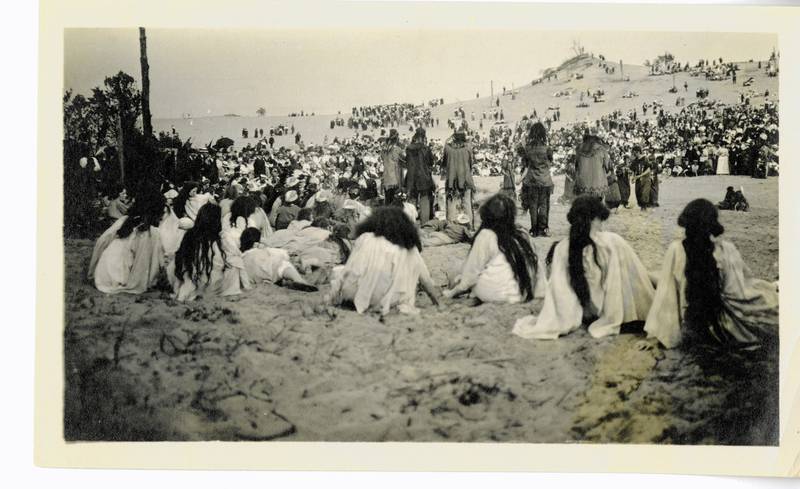

Undaunted, the National Dunes Park Association (NDPA) and other preservation groups were determined to continue the save the dunes campaign. Supporters took the Prairie Club's annual outdoor festival concept and expanded it into a historical pageant called "The Dunes Under Four Flags." The dunes pageant would tie the area to American history while portraying the beauty of the duneland through dance, music, and poetry. The Dunes Pageant Association, incorporated in Chicago in February 1917, commissioned Thomas Wood Stevens, president of the American Pageant Association, to compose a pageant similar to his other successful shows in Newark and St. Louis. Memorial Day 1917 was the first performance at the Waverly Beach blowout—a natural amphitheatre amidst the sand dunes—in the present-day state park. It was rained out, but the following weekend, 25,000 people jammed into the area for an unforgettable pageant with 600 actors. It was capped by a stirring grand finale, singing the national anthem.

Image caption: Dancers of the pageant in white gowns are seated in the sand behind the crowd; spring, 1917. (Westchester Township History Museum)

The pageant enjoyed widespread publicity thanks to area women's clubs. Newsreels spread the event throughout the country. Petitions proliferated. Each member of Congress received a copy of the pageant brochure. One author contends the pageant spawned a civil religion and a formidable political constituency for saving the dunes by creating a "community united by mutual sympathy."

As United States involvement in the war deepened, NDPA members acknowledged their inability to halt the despoiling of the dunes during the conflict. They vowed to renew the fight "the minute the war is over." They kept the issue before the public, however, as witnessed by what one Chicago columnist wrote in 1918:

Unless the State of Indiana or the United States takes the matter in hand, commercial plants will crowd the entire lake frontage. The matter resolves itself into a decision of humanity. Shall the million[s] of mill workers be condemned to the slavery of labor without recreation in the big plants on the lake shore, or shall they be given the privilege of open-air spaces and pure air in which to renew strength and courage in their brief hours away from the mills?

While the war ended in late 1918, the Sand Dunes National Park initiative floundered badly in 1919, faced by the post-war prosperity and the mounting opposition of politicians and business interests. Evidence of this fatal NDPA pessimism can be seen in the May 15, 1919, meeting of the Chicago committee. The group conceded that a prolonged educational campaign was needed to convince Congress to "purchase" the national park. After that arduous process, there would be no dunes left to save. The group admitted the NDPA should drop the national park struggle and pursue administration of the Indiana Dunes by the State of Indiana itself.

An Indiana Dunes State Park

Origins of Indiana's interest in establishing its own State Park System began in 1916, when an Indianapolis business leader and municipal reformer recommended the State establish its own park system. A member of the Indiana Historical Commission (IHC—overseer of the State centennial), Richard Lieber found himself chairman of the IHC's State Park Memorial Committee. By the end of the year, Lieber succeeded in raising private funds to purchase McCormick's Creek Canyon and Turkey Run which became Indiana's first state parks. Lieber also called for the acquisition of a portion of the Indiana Dunes for a state park. In 1919, the Indiana Legislature approved the formation of the Department of Conservation and Republican Governor James P. Goodrich appointed Lieber its first director.

By late 1920 or early 1921, National Park Service Director Stephen Mather and Assistant Director Horace Albright were convinced the fight for establishment of the Sand Dunes National Park was fruitless. Combined with scant political support in Indiana, the new Federal administration of Warren G. Harding ushered in a new era of Republican conservatism which nixed the plan. No dunes park bill was introduced before Congress. More importantly, Mather and Albright no longer believed in the cause. With industry's relentless push on each end of the lakeshore, Indiana Dunes was "unacceptable for National Park status." Albright recalled, "Mr. Mather was just too busy to get back to the Dunes project and he gradually came to the conclusion that the only hope for them lay in the state park movement."

Mather abdicated saving the dunes to his friend Richard Lieber. Both men organized the first national meeting of state park employees in 1921. Two years later, they reassembled at Turkey Run State Park where the National Conference on State Parks formed with Mather the first president and Gary's Bess Sheehan (NDPA officer) its secretary. Indiana's park system was the model in the United States and its leader redoubled his efforts to add the Indiana Dunes to its fold.

Image caption: The National Park Service inspection tour of the proposed Sand Dunes National Park included the following (beginning with the first full figure at the right): unknown, Dr. Henry Chandler Cowles; Mrs. Bess Sheehan; unknown; National Park Service Director Stephen T. Mather (partially obscured); Col. Richard Lieber; unknown; and Horace M. Albright. (Photographer unknown, October 31, 1916, Photographic Archives, Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore)

Lieber and Sheehan would find success, establishing Indiana Dunes State Park in 1925 and ultimately protecting 2,500 acres of unspoiled Duneland. The second push for securing a national park in the Indiana Dunes would not begin for another quarter century under the lead of Dorothy Buell, Senator Paul H. Douglas, and the Save the Dunes Council.

Learn More

- Explore more conservation history of Indiana Dunes National Park here:

A Signature of Time and Eternity

- Find Mather's full report here:

Report on Proposed Sand Dunes National Park

- Learn about his plaque at Indiana Dunes National Park here:

Stephen Mather Memorial Plaque (Lake View)

Sources

- Cockrell, Ron; A Signature of Time and Eternity: The Administrative History of Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore, Indiana, National Park Service, 1988.

- Mackintosh, Barry; National Park Service: The First 75 Years, National Park Service, 1991.