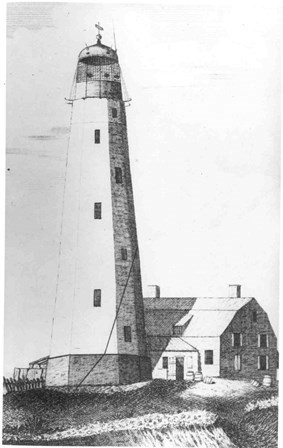

NPS ARCHIVES Prequel: Sandy Hook, Key to The City To enter New York Harbor, ships need a deep channel. Until the 1900s, that meant sailing next to the shore of Sandy Hook. This gave the small peninsula a big role in the safety and defense of New York Harbor for more than a century before Fort Hancock was built. In 1764, the Colony of New York built Sandy Hook Light to assist navigation. Because the lighthouse helped ships sail safely to New York Harbor, the structure has always had inherent military value. As a result, a military presence quickly followed its construction and has remained more or less since the American Revolution. In early 1776, Sandy Hook peninsula was easily captured by the British. In June 1776, Continental Army Lt. Col. Benjamin Tupper led his artillery to destroy the lighthouse, "but found the walls so firm I could make no Impression." Unlike most of New Jersey, both the Sandy Hook Lighthouse and New York City remained in British and Loyalist hands until the war's end in 1783. Loyalists guarded the Light for the remainder of the War, using the Hook to stage raids on patriot-held areas in New Jersey. The cannonball-dented remained visible until repairs took place just before the Civil War, when the walls were thickened considerably.

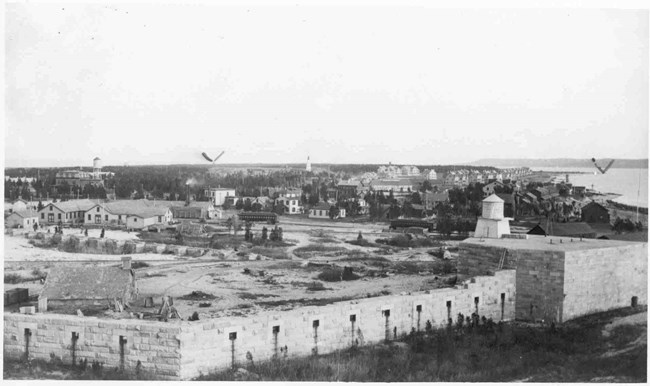

NPS ARCHIVES The U.S. Army Arrives The military history of the Sandy Hook peninsula expanded along with the nation itself. See the timeline page for important dates. In 1806, landowner Richard Hartshorne transferred most of northern Sandy Hook to the Federal Government for military use. By 1817, all final transfers of land ownership were complete. During the War of 1812, a wooden fortification named Fort Gates was constructed in 1813, an example of what is now called the Second System of defense. The lighthouse itself was armed with cannon. After the War of 1812, recommendations were made to construct a large permanent fortification at the end of the Hook, but it wasn't until just before the Civil War began that work began. Over the next three years, a large wharf was constructed to receive new building supplies and materials and the fortification of the fort was laid out. In 1859, the U.S. Army began to construct the Fort at Sandy Hook. It also served as a camp for the 10th New York Volunteer Infantry, or the "National Zoauves." The fort was never completed, however, and was deserted after the war. (The granite structure was largely torn down by the Army in the 1950s.) This represented the Third System of defenses. Starting in 1890, the Army constructed the first of many concrete gun batteries of the Endicott era. Next were Taft Defenses that included changes to existing fortifications and the addition of 12-inch barbette guns. (The Army also created the Sandy Hook Proving Ground in 1874, which was run as a separate entity until it was deactivated when the Aberdeen Proving Ground was established in Maryland in 1919.)

NPS ARCHIVES Fort Hancock Historic Post: In 1895, the U.S. Army renamed the "Fortifications at Sandy Hook" as Fort Hancock. The installation would protect New York Harbor from invasion by sea. Its yellow brick buildings were constructed largely between 1898-1910, with the fort reaching its peak population in World War II. Fort Hancock's defenses waxed and waned with the needs of the nation from the end of the Spanish-American War through the end of World War II. The core of the fort was referred to as the Main Post (now Fort Hancock Historic Post). The fort's population peaked during World War II to more than 7,000 soldiers. These included members of the Women's Army Corps, who were housed in Barracks 25. Male soldiers, who called it the "WAC Palace," were denied entry. African-American soldiers also worked and lived here in a move that predated the overall desegregation of the Army, which occurred in 1947 by an executive order from President Harry S Truman. Aircraft changed the style of warfare forever, and by the end of World War II anti-aircraft guns had taken over the key defensive role at Fort Hancock. The Cold War era brought a change from anti-aircraft guns to Nike Missiles that could intercept jet warplanes. These surface-to-air nuclear missiles were housed here between 1954 and 1974. The fort was decommissioned on December 31, 1974. Since then, most of Fort Hancock has served the public as the Sandy Hook Unit of Gateway National Recreation Area. The remainder of the peninsula serves as U.S. Coast Guard Station Sandy Hook. The Fort Hancock and Sandy Hook Proving Ground National Historic Landmark covers the entire peninsula, including what is now under the jurisdiction of the U.S. Coast Guard. Visitors may tour gun batteries and the historic post as well as enjoy Sandy Hook's trails and beaches. Brochures and more about Fort Hancock Defenses of Sandy Hook Dig deeper: Historic Structural, Landscape and Other Reports Several structures at Fort Hancock Historic Post have been the subject of various historical surveys. These are not light reading but include a great deal of information for the scholar or the enthusiast. They also can be quite lengthy and may time a lot of time to download. These historic resource studies provide extensive information about Army operations across all of Fort Hancock as well as the Sandy Hook Proving Ground during its operational period. General reports: |

Last updated: March 18, 2024