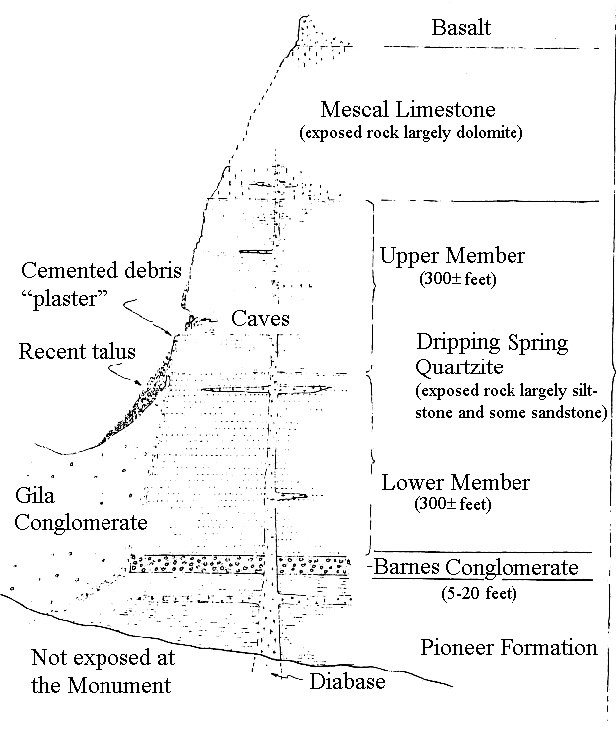

Why is This Important?The geology of Tonto National Monument played an essential role in the lives of the Salado people. Studying the geologic features of the Monument allows archeologists to understand the Salado’s access to natural resources. Exposed RocksThe rocks exposed at the Tonto National Monument are principally sedimentary rocks of the Apache Group and the distinctive Gila conglomerate. Some bodies of diabase are present, and a veneer of relatively recent rock debris covers parts of the lower slopes and canyon floors. BasaltA thin flow of Precambrian basalt caps the Mescal limestone. The basalt is a dense, fine-grained, dark gray to black rock, generally with a distinctive dark-reddish cast. It commonly contains scattered larger crystals of a lighter colored feldspar mineral. This basalt was not used by the Salado for implements and utensils. Mescal LimestoneThe Mescal limestone, which overlies the Dripping Spring quartzite, caps many of the hills at the Monument. The Mescal here is light gray dolomite (calcium magnesium carbonate) near diabase bodies, though some limestone may be present at the Monument. The term “limestone” is part of the official name of the Mescal. It does not accurately reflect the composition of the Mescal at Tonto National Monument where the Mescal is largely composed of dolomite. Dripping Spring QuartziteAlthough the Lower and Upper Cliff Dwellings are at different altitudes, they are both in the same layer of Dripping Spring quartzite. The rocks of the Dripping Spring quartzite are composed mainly of quartz and feldspar, but they also contain a very small amount of carbon and extremely fine grains of pyrite throughout the rock.

Barnes ConglomerateThe Barnes conglomerate, 5 to 20 feet thick, overlies the Pioneer formation. In turn, it is overlain by the Dripping Spring quartzite that consists of a lower member (composed of reddish brown sandstone and quartzite) and an upper member (composed of platy to massive black, gray, red, and brown claystone, siltstone, sandstone, and quartzite). The Barnes conglomerate consists of rounded, water-worn pebbles of older rock, but the varying size indicates they did not travel far. Gila ConglomerateGila conglomerate is the second youngest rock seen at the Monument. It was deposited between half a million and fifteen million years ago, after many geologic events had affected the older rocks of the area. The Gila conglomerate is valley-fill material principally composed of gravel conglomerate, which is lithified gravel (gravel hardened or cemented to a competent rock) and a few beds of sandstone and siltstone. The rock is commonly pale yellow and buff in color and poorly stratified and sorted, as indicated by areas that contain rock debris ranging in size from clay particles to boulders several feet in diameter. DiabaseDiabase was intruded into the older rocks after the outflow of basalt of the Mescal probably in Precambrian time between half a billion and one billion years ago. The diabase forms sills (tabular bodies of rock that were intruded in a molten state parallel to bedding planes), dikes (tabular bodies that cut across older rocks), and irregularly shaped masses. |

Last updated: June 20, 2021