The origins and movement of the Salado inhabitants of the Tonto Basin has perplexed archeologists for many years. Between A.D.1250 to 1450 the Salado people influenced a large number of cultural groups within the southwestern United States through their iconographic pottery designs. The spread of the Salado culture became known as the Salado Phenomenon. What Does Salado Mean?The term Salado comes from the Spanish name Rio Salado, or the Salt River, that runs from the White Mountains in eastern Arizona through the Tonto Basin to the canyons of central Arizona (Houk 1992). The term Salado, when used in reference to southwestern archeology, can have three different meanings

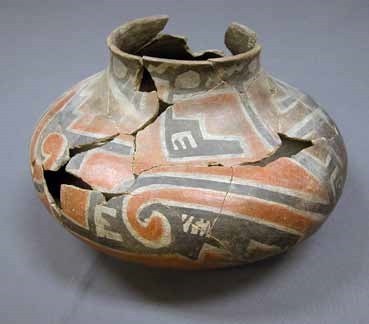

Here we reference the first definition for Salado, a cultural group. In 1930, Harold and Winifred Gladwin of Gila Pueblo Archaeological Foundation in Globe, AZ introduced the term Salado in print to refer to a cultural group having distinct features. Gladwin states: “Salado is the name suggested to cover the remains of the people who colonized the Upper Salt River drainage, and who developed various specialized features in the region adjacent to Roosevelt Lake” (Houk 1992:2). The distinct features included multistoried adobe structures and polychrome pottery. Gladwin proposed that the Salado people were Puebloans who moved southwest from the upper Little Colorado River area around A.D. 1000 (Clarke 2001) Gladwin thought that a second migration occurred by people from around the Four Corners region bringing the Puebloan architecture and Gila polychrome ware influence (Clarke 2001). Other archeologists have theorized how the Salado culture developed in the Tonto Basin, and who the Salado people were. Emil Haury suggested that the Salado people developed through the amalgamation of northern Anasazi groups and eastern Mogollon groups who migrated to the area (Clarke 2001: Houk 1992). Today archeologists continue to debate this topic. Some think that the Salado formed through an influx of Mogollon people from the south and the Phoenix Basin Hohokam people from the southeast into the lower Tonto Basin. Many archeologists believe that a group of local inhabitants, residing in the area since Archaic times, who interacted with the Hohokam composed the Salado culture.

Salado ContextThe Salado phenomenon has two different patterns identifiable in both regional and local contexts. The “Local Salado” is the Salado cultural pattern in the Tonto Basin that becomes distorted the further away from the center of the basin a group resides (Dean 2000). The “Regional Salado” is characterized by Salado polychrome ceramics that cannot take on a specific definition because the pottery is found in a variety of contexts (Dean 2000). As stated above, the Salado polychrome wares date to the Roosevelt and Gila Phases. The following descriptions of each phase refer to the Local Salado cultural pattern.

The Spread of Salado IconographyThe spread of the Salado Polychrome iconography across the region may have been a response to the turmoil in the area during 1250-1450 A.D. Regional and local environmental crises, such as droughts, would have increased the uncertainty of food production thus exaggerating social inequalities, unequal access to resources, and unequal distribution of wealth (Dean 2000). Many communities were mobile during this period causing different social group interactions, ethnic mixing, and the displacement of established groups in the region. These changes would require the development of new methods for incorporating immigrants into established communities, interacting with other social groups, managing internal and external disputes, and organizing multiethnic communities (Dean 2000). In the 1990s Patricia Crown identified the Regional Salado phenomenon as a regional religious cult. Crown (1994) suggests that the appearance of Salado Polychrome wares across the southwest and into Mexico is an expression of a regional religious system. In her view, the pottery represents the symbolic expression of a religious or ideological movement she calls the Southwestern Cult. Through her research, Crown determined that Salado Polychrome vessels were often locally made at the sites where they are found and not imported. She suggests that people across the southern Southwest were adopting new symbols representing a new religious belief system. The iconography represents an easily transmittable ideological system (i.e. through pottery) that could have helped to more easily facilitate the changes within the region and be adapted to fit certain community’s needs (Dean 2000). However, this is not normally how the spread of a homogeneous ideological cult occurs across societies. If the Salado Phenomenon spread from the Tonto Basin fulfilling the above problems through situational adaptations, researchers may not be able to identify diagnostic elements of the Southwest Cult to understand how the cult was organized into a system. For example, Dean (2000) suggests that the spread of the Katsina Cult to the north of Tonto Basin through the distribution of Jeddito Yellow Ware Ceramics and design styles may represent a parallel northern response to similar environmental problems. However, unlike Salado polychromes Jeddito Yellow ware was produce in and disseminated from a single area in the Hopi Mesas. The Movement of the SaladoThe Salado began migrating out of Tonto Basin leaving the large, platform mound communities after A.D. 1350. By A.D. 1450 the people of Tonto Basin moved on to other places. Reasons causing people to leave this area vary. Some archeologists suggest that cycles of droughts and floods negatively affected agricultural practices, or the presence of warfare and conflict were important reasons for people leaving. The origins and disappearance of the Salado culture in Tonto Basin remains a mystery. However, the influence of the Salado people covered a large portion of the Southwest and can be identified in the archeological record through the spread of the Salado polychrome iconographic and design styles. Literature Cited:

|

Last updated: June 16, 2021