|

Frank H. Zeile was a resident of Roosevelt, Arizona between 1920 and 1927. He worked as an oiler on the Roosevelt Dam and in his spare time, took some of the first photographs of Tonto National Monument. Copies of his photos were later donated to Tonto National Monument by his grandson, Scott Wood. For over 40 years, Scott was the archeologist for Tonto National Forest until he retired in 2015. The following is an interview conducted by Tonto National Monument's intern, Dani Herzner.

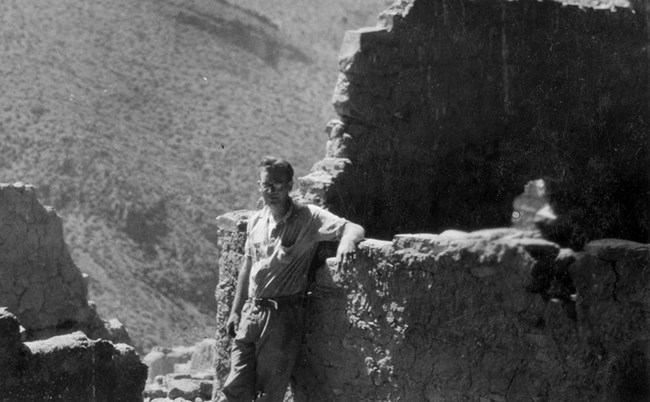

NPS Photo/Courtesy of S. Wood S. Wood: My earliest memory of the Monument is from the 1960s when I was in high school and had already decided to become an archeologist. Even then [the cliff dwellings] looked a lot different from his photos. Unfortunately, [my grandfather] died when I was 12 and we never really had a chance to talk about his experiences. DH: What was your grandfather's occupation? Was he just a hobby photographer? SW: When he lived in Roosevelt he worked for the Salt River Project as an oiler on one of the generators at the dam. Photography was one of his hobbies, along with collecting baskets and stuff from the Apaches who lived just down the road (which my Grandmother later threw away!), visiting ruins with Lyn Hargrave, and playing with his jazz band. DH: Did he take any photographs that stood out to you or impacted you? SW: The sequence of photos of the Savoia-Marchetti seaplane and its arrival and subsequent destruction at hotel Point in 1927. Great stuff! DH: How did you come to have the photos? Did he hand them down to you? If so, why you? SW: My mother gave them to me years after he died, knowing that I was interested in the history and archeology of the Tonto Basin.

NPS Photo/ F. Zeile SW: I gave Duane [Superintendent of Tonto NM] copies years ago. I figured he'd want some record of how the place used to look before all of the stabilization. DH: You were the Tonto National Forest archeologist for over 40 years. Did your grandfather or his photographs play a role in your career choice? SW: Yeah, I suppose he/they did- a sort of family connection to the history and prehistory of the Tonto Basin. DH: What was it like working as an archeologist in an area that so many people, including your grandfather, visit for the cultural and historical resources? SW: Hard to put into words really, but it was satisfying enough to keep me there for a few years... Working on [Tonto National Monument] as an archeologist is sort of like a dream job in many ways- the best, most interesting archeology in the southwest (in my humble opinion) and great opportunities for public engagement and interpretation. DH: What has been one of your most exciting discoveries? SW: I wish I had a nickel for every time somebody has asked me that... for some, maybe most, archeologists, "discoveries" in the physical sense- sites, artifacts- are the thing, but for me, the story was always the thing, what we learn from all of the accumulated discoveries, each as important as the next or the last, all of them helping to tell the story of what happened in the past. That's the most exciting "discovery" to me, and it changes all the time with each new thing we learn.

NPS Photo/ F. Zeile SW: Difficult question. First of all, you can never preserve anything exactly the way you found it- sites transform over time; they are different every time you visit them. Still, what I tell visitors and others interested in archeology consists pretty much of all clichés- every site vandalized is like a page ripped out of a book, etc. I could go on and on about this, but site preservation/conservation is a complex subject involving a fine balance between protecting things for an uncertain future in which there may well be no protection weighed against recovering information that is constantly degrading and may eventually disappear all on its own. We often talk about saving sites for the new, higher tech methods of study we will supposedly have in the future even though there is no guarantee that those methods will ever be developed or that the sites we are saving for them will even be preserved to study. Are two birds in the bush really as valuable as one in the hand? How do you balance the need to know against the desire to preserve? Like I said, a lot of philosophical conflict, so I just tell visitors that every site has a part to play in the telling of the story and that the story can never be completed if those parts are removed or so damaged they can't be interpreted- so don't break anything and leave stuff where you found it! DH: By taking those photographs, your grandfather documented history and created a vantage point that today's visitors no longer have. And by donating those pictures, you provided the opportunity for future visitors to observe how the dwelling once looked, as well as for the National Park Service employees to study and learn when and how the cliff dwelling deteriorated and how to use preventative methods against further damage. If you could photograph one thing for future generations, what would it be? SW: That's the question, isn't it? You never know what will be important in the future or what will happen to the things that we have today, so how do you decide? For an archeologist, the answer is easy- everything! DH: What would you tell your grandfather today if you saw him on the walls of the Salado cliff dwellings? SW: I'd tell him to get down from there- carefully.

A picture is worth a thousand words, and Frank Zeile's photographs give us a window to the past as natural and human destruction has drastically changed the Salado structures into what we see today. It's no coincidence that his grandson, Scott Wood, was drawn to the study and preservation of these structures and other archeological sties in the area. The awe and respect for ancient sites such as Tonto was obviously passed down through their family; hopefully it continues to spread through today's society. It is important that when you visit ancient sites or stumble upon artifacts to remember the past of these treasures and think of the future generations that have the right to see them just as you do. Tonto National Monument is just one site in Arizona that contains substantial cultural history. Thanks to Mr. Wood and Zeile, we are able to see how the Salado lived as well as how the cliff dwellings looked a hundred years ago! -Written by D. Herzner |

Last updated: October 11, 2020