The Navajo “Mobile Unit,” 1940The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) was one of the most popular of President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal programs of the 1930s. This Great Depression program provided work for unemployed young men. Because their work focused on conservation, the “Tree Army” camps were often located in national parks and monuments. A special unit of the CCC worked at Tonto National Monument for several months in the spring of 1940. But these men, members of the CCC Mobile Unit, were unlike the Conservation Corps that people typically remember.

In 1937, the National Park Service hired Gordon Vivian – an archeologist with experience at Chaco Canyon – to train and supervise the newly organized enrollees of the Navajo Mobile Unit. Work in the ancient structures at Chaco – places where the Old Ones had lived and died – did not necessarily fit well with traditional Navajo culture. So why were the men attracted to the Civilian Conservation Corps? Economics was an important factor. A cash income had always been difficult on the reservation, and the depression made it worse. A regular paycheck was an important incentive. Vivian had only one complaint about his first twenty-five recruits: the Navajo men had little patience for the mandatory safety meetings. As Foreman Vivian reported, when asked if they had any questions about the first aid lessons, the reply was often, “Yes, when do we get our checks?” A regular thirty-dollar monthly paycheck was a good reason to join the Mobile Unit – in spite of weekly safety meetings. Soon an experienced and highly skilled cadre was developed, and the men were willing and able to travel to other national monuments where their work was needed.

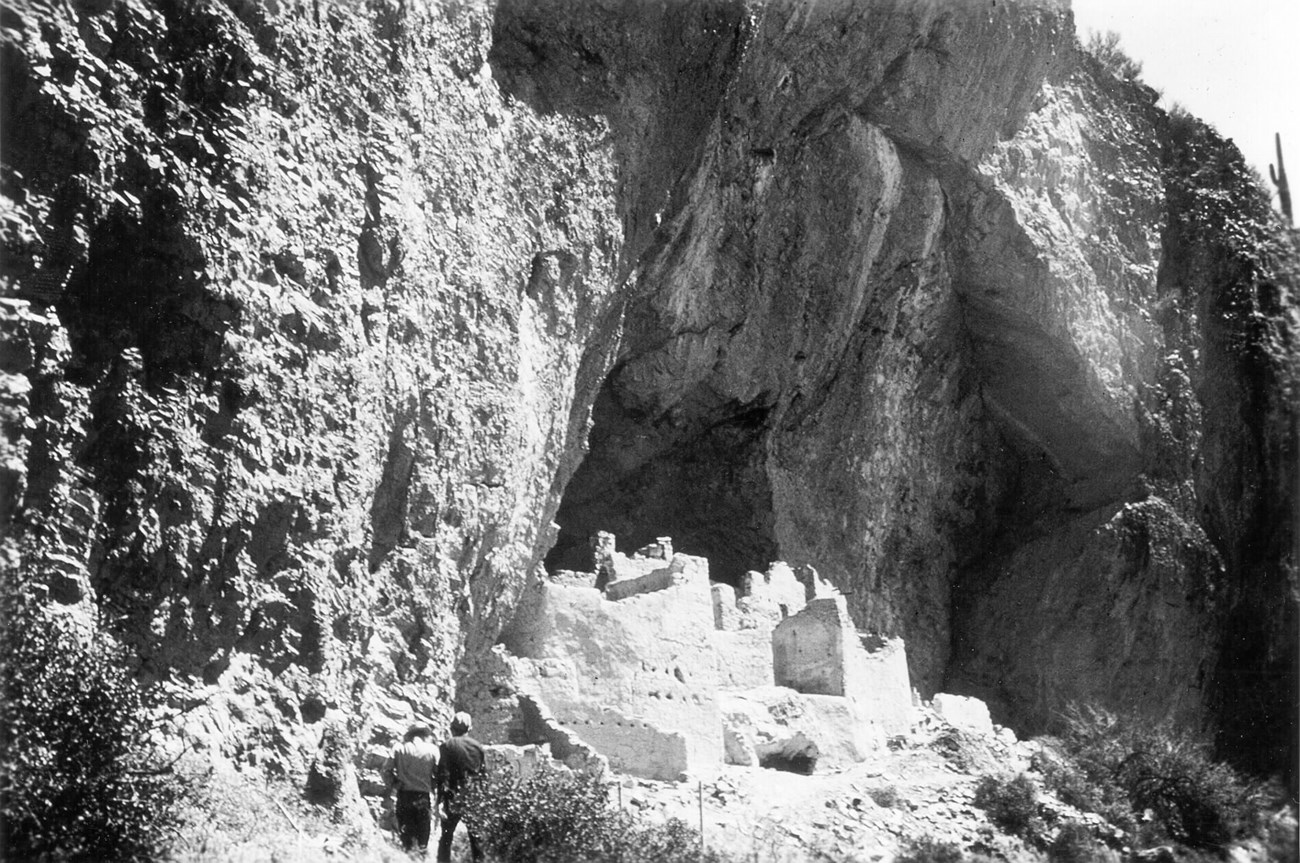

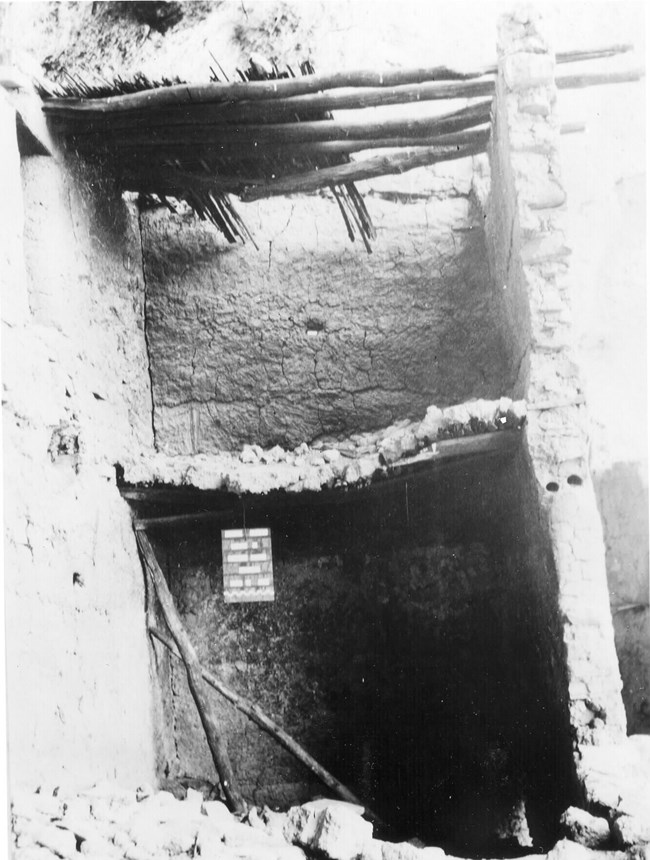

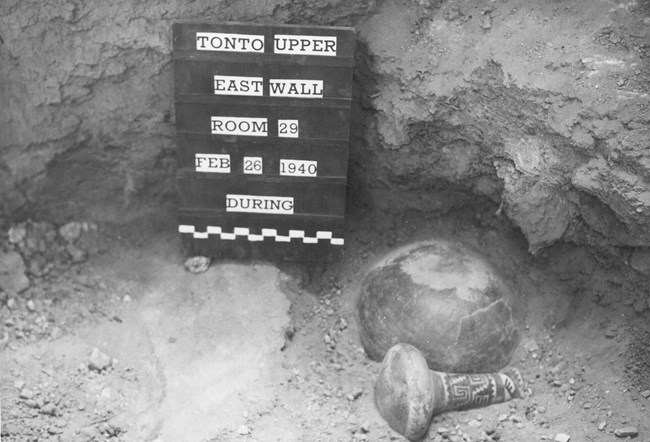

At the Upper Cliff Dwelling, one wall in particular was in danger of falling. Steen called it his “problem child wall,” and made it a priority for stabilizing. But first, still in January, the crew excavated several rooms for artifacts. Baskets, sandals, pottery, and tools were among the items collected. Cleaning and sorting pot sherds became a regular part of the men’s work. Besides the important excavations and stabilization, the creation of the Mobile Unit led to improved cultural awareness and understanding. As both Vivian and Steen could attest, they all had much to learn from each other. The relationship between the Navajo Nation and the federal government – including the National Park Service – had never been easy, and at times was stressed to the breaking point. The Mobile Unit represented one small effort to mend that relationship, as well as mending the walls built by the ancestral peoples.

When World War II came, the Civilian Conservation Corps was disbanded. 1942 saw the last of the Tree Army, including the Indian Division. Park visitors still can see the results of Conservation Corps work throughout the nation, including visitor centers, trails, and campsites. At Tonto National Monument’s Upper Cliff Dwelling the critically important work of the Navajo Mobile Unit is still visible. Native American participation with archeology did not end with the CCC however. In recent decades, many tribal governments have developed their own archeological programs. During the spring of 2022, the White Mountain Apache Archeology Division assisted the staff at Tonto, as we once again worked to stabilize vulnerable walls at the Upper Cliff Dwelling – more than eighty years after the Navajos of the Mobile Unit worked on those walls and built that trail. |

Last updated: November 4, 2022