Mission Santa Cruz de San Sabá and Presidio San Luis de las Amarillas

Menard, Texas

Coordinates: 30.922472, -99.801700

#TravelSpanishMissions

Discover Our Shared Heritage

Spanish Colonial Missions of the Southwest Travel Itinerary

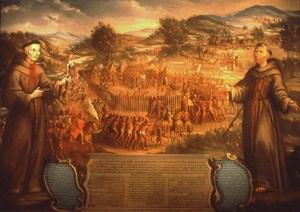

Attributed to Jose de Paez, 1765. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Photograph by mlhradio via Flickr and creative commons license

Drawing by Arthur Schott, United States and Mexican Boundary Survey. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Mrs. Joseph Harrison, Jr.

Photo by Larry D. Moore, 2010, CC BY-SA 3.0. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Plan Your Visit

Mission Santa Cruz de Sabá is designated by the Texas Historical Commission marker located on Ranch Road 2092 (Farm to Market Road 2092), on the left when traveling east from Menard, TX. The site of Presidio San Luis de las Amarillas, also known as Presidio San Sabá, is on the National Register of Historic Places and is located one mile west of Menard, TX on US 190 at 191 Presidio Rd. Admission is free, and the presidio is open daily with staff on site. For more information, visit the Presidio San Saba website or call 325-396-4682.

Last updated: October 31, 2017