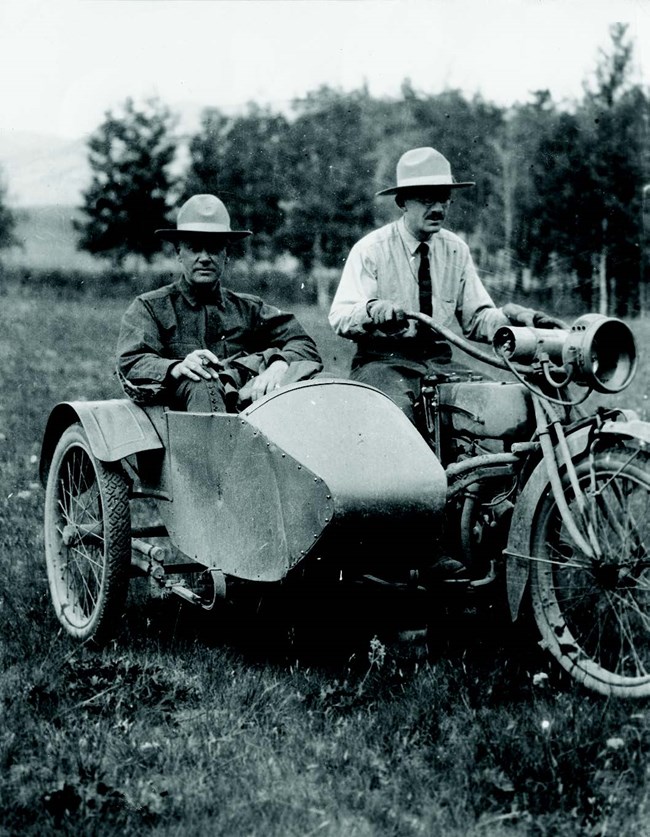

Yellowstone National Park, 1923

National Park Service Historic Photograph Collection/George A. Grant

In 2016, the National Park Service will be celebrating its 100th birthday. On August 25, 1916, President Woodrow Wilson signed the Organic Act creating the National Park Service, a federal bureau in the Department of the Interior. This act states, “the Service thus established shall promote and regulate the use of Federal areas known as national parks, monuments and reservations…which purpose is to conserve the scenery and the natural and historic objects and the wild life therein and to provide for the enjoyment of the same in such manner and by such means as will leave them unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations.”1

To commemorate that milestone, the National Park Service is planning its Centennial, with a goal of connecting with and creating the next generation of park visitors, supporters, and advocates. The National History Day theme for 2016, Exploration, Encounter, Exchange in History, provides a unique opportunity for students and teachers to engage in the many stories and primary resources preserved by the National Park Service and join in the Centennial commemoration.

The history of the National Park Service actually begins before the Organic Act of 1916. As early as the 1830s, concern arose over the settlement of the western territories and the impact of westward expansion on wilderness, wildlife, and Native American populations. Native American portrait artist George Catlin noted during a trip to the Dakotas that “some great protecting policy of government…in a magnificent park…a nation’s park” could preserve the wilderness and resources.

In 1864, Congress bequeathed the Yosemite Valley to the state of California, to be preserved as a state park. Although Yosemite was recognized by Congress as a national treasure worthy of preservation, it was not until 1872 that the region was delegated to the U.S. Department of Interior, to be designated as the world’s first national park. Because the department had no central agency to administer the park, Army troops were detailed to provide protection, enforce hunting and grazing laws, and assist with the visiting public.

The next two decades of the nineteenth century saw the creation of more national parks in western lands for preservation of wilderness and natural beauty. Among those are Sequoia, Mount Rainier, Crater Lake and Glacier national parks. The state of California also returned the Yosemite Valley back to the Department of Interior during that period, to become a national park. Increasing public interest in ancient Native American culture led to additional areas being established by Congress as national parks. The first of these was Arizona’s Casa Grande Ruin, created in 1889, followed by Colorado’s Mesa Verde National Park in 1906. Those areas preserved unique cliff dwellings, ruins or other artifacts. Along with the creation of Mesa Verde National Park, Congress would, in 1906, pass the Antiquities Act, which authorized the establishment of national monuments by the president to preserve

“historic and prehistoric structures, and other objects of historic or scientific interest.” 2 Under Theodore Roosevelt’s administration, 18 national monuments were declared through authority of the Antiquities Act. They included historical or cultural sites like the petroglyphs at El Morro, New Mexico, and natural wonders like the Grand Canyon, which would later be converted to a national park by Congress.

A crisis in the competition between conservationist and business interests came when the city of San Francisco lobbied to dam Yosemite’s Hetchy Valley to create a reservoir. Strict natural preservationists like John Muir called on Congress to ban the dam, to preserve the area’s natural wilderness. In 1913, however, Congress permitted that dam to be built. Preservationists came to the conclusion that a centralized agency was needed to oversee

and coordinate management of national parks. Wealthy businessman and park preservation supporter Stephen T. Mather was called on by the secretary of the Interior in 1915 to serve as his assistant regarding park affairs. Horace M. Albright was appointed as Mather’s aide. Mather and Albright set to work to promote the creation of a national parks bureau, pointing to the economic benefits of tourism in national parks through a media campaign in magazines and railroad tourism publications. In 1916, Congress would respond to that campaign, passing the Organic Act, which created the National Park Service. Stephen T. Mather was selected by Secretary of the Interior Franklin K. Lane to serve as the Park Service’s first director.

The first 100 years of the National Park Service would see eras where presidents favored expansion and establishment of new parks and areas, as well as periods under other administrations more interested in maintaining and preserving existing parks. A major 10-year initiative instituted in the 1950s, known as Mission 66, sought to rebuild park infrastructure and create new visitor centers that provide expanded exhibits, audiovisual programs and other public services. President Jimmy Carter signed the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act of 1980, which would double the size of the National Park System by adding over 47 million acres of wilderness to its management. As we approach

the 100th anniversary of the Organic Act, the National Park Service has recommitted to connecting with the public and re-establishing itself as the world’s largest informal educational agency.

1 “Organic Act of 1916,” National Park Service, accessed January 23, 2015, www.nps.gov/grba/parkmgmt/organic-act-of-1916.htm. “American Antiquities Act of 1906,” National Park Service, accessed January 23, 2015, www.cr.nps.gov/local-law/anti1906.htm.

2 “American Antiquities Act of 1906,” National Park Service, accessed January 23, 2015, www.cr.nps.gov/local-law/anti1906.htm.

This article has drawn much of its content from “The National Park Service: A Brief History,” by Barry Mackintosh.

Rosenblum, Linda, Katherine Orr, and Nicholas Murray. "To Provide for the Enjoyment for Future Generations: The First 100 Years of the National Park Service." In National History Day 2016: Exploration, Encounter, Exchange in History, edited by Lynne O'Hara, 31-35. 2016.

Last updated: June 3, 2021