NPS

Defining Key Terms

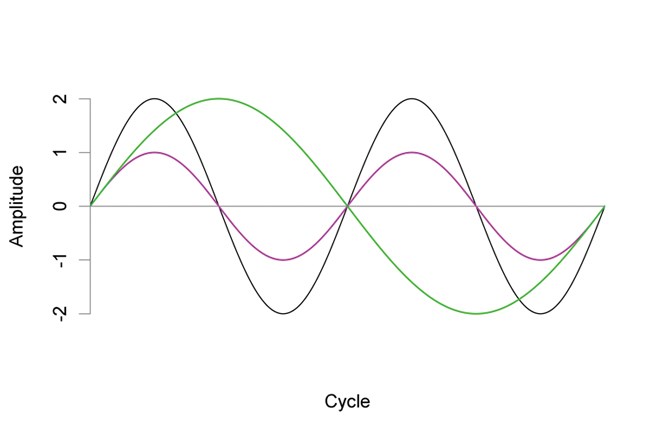

Sound moves through a medium such as air or water as waves. It is measured in terms of frequency and amplitude.

Frequency, sometimes referred to as pitch, is the number of times per second that a sound pressure wave repeats itself. A drum beat has a much lower frequency than a whistle, and a bullfrog call has a lower frequency than a cricket. The lower the frequency, the fewer the oscillations. High frequencies produce more oscillations. The units of frequency are called hertz (Hz). Humans with normal hearing can hear sounds between 20 Hz and 20,000 Hz. Frequencies above 20,000 Hz are known as ultrasound. When your dog tilts his head to listen to seemingly imaginary sounds, he is tuning in to ultrasonic frequencies, as high as 45,000 Hz. Bats can hear at among the highest frequencies of any mammal, up to 120,000 Hz. They use ultrasonic vocalizations as sonar, allowing them to pursue tiny insects in the dark without bumping into objects.

At the other end of the spectrum are very low-frequency sounds (below 20 Hz), known as infrasound. Elephants use infrasound for communication, making sounds too low for humans to hear. Because low frequency sounds travel farther than high frequency ones, infrasound is ideal for communicating over long distances.

NPS / Damon Joyce

See Types of Data for information on how NPS acoustic technicians use frequency and amplitude in field assessments.

Decibels are measured on a logarithmic scale, so an increase of 10 dB causes a doubling of perceived loudness and represents a ten-fold increase in sound level (Crocker, 1997). In other words, if the sound of one vacuum cleaner measures 70 dB, 80 dB would be the equivalent of 10 vacuum cleaners.

Acoustic resources are physical sound sources, including both natural sounds (wind, water, wildlife, vegetation) and cultural and historic sounds (battle reenactments, tribal ceremonies, quiet reverence). Soundscape can be defined as the human perception of those physical sound resources. Like beauty, soundscapes are in the mind of the beholder. The rhetorical question about the tree that falls in the forest may help illustrate this. Because no human is there to hear it, the resulting crash is not a part of the human soundscape. It is however, a pretty significant part of the soundscape of the squirrel standing in the tree's path.

The acoustic environment is the combination of all the acoustic resources within a given area. This includes natural sounds and cultural sounds, as well as non-natural human-caused sounds. The sound vibrations made by our imaginary falling tree are a part of the acoustic environment regardless of whether a human is there to perceive them. Bat echolocation calls, while outside of the realm of the human soundscape, are also part of the acoustical environment. It is therefore critical to take the entire acoustic environment into account when working to protect natural sounds.

Because the acoustic environment is made up of many sounds, the way we experience the acoustic environment depends on interactions between the frequencies and amplitudes of all the sounds. Sound levels are often reduced or adjusted ("A-weighted") to match the hearing abilities of a human or given animal. Sound levels adjusted for human hearing are expressed as dB(A).

Sound Level

Sound levels in national parks can vary greatly, ranging from among the quietest ever monitored to extremely loud. While the din of a typical suburban area fluctuates between 50 and 60 dBA, the crater of Haleakala National Park is intensely quiet, with levels hovering around 10 dBA. Along some remote trails in Grand Canyon National Park, sound levels, at 20 dBA, are softer than a whisper. The noise levels of a cruiser motorcycle at Blue Ridge Parkway, however, can be compared to standing near a churning garbage disposal.

Decibels work on a logarithmic scale; an increase of 10 dB causes a doubling of perceived loudness and represents a ten-fold increase in sound level. Thus 20 dBA is perceived as twice as loud as 10 dBA, 30 dBA would be perceived as 4 times louder than 10 dBA, 40 dBA would be perceived as 8 times louder than 10 dBA, etc. Below are some examples of sound pressure levels measured in national parks.

Read more about noise effects in parks, and what parks are doing to address it.

| Sound Level (dBA) | Sound Source |

| 0 | Threshold of human hearing |

| 10 | Volcano crater (Haleakala National Park) |

| 20 | Leaves rustling (Canyonlands National Park) |

| 40 | Crickets at 5 m (Zion National Park) |

| 60 | Conversational speech at 5 m (Whitman Mission National Historic Site) |

| 80 | Cruiser motorcycle at 15 m (Blue Ridge Parkway) |

| 100 | Thunder (Arches National Park) |

| 120 | Military jet at 100 m AGL (Yukon-Charley Rivers National Park) |

| 126 | Cannon fire at 150 m (Vicksburg National Military Park) |

Last updated: July 3, 2018