Cultural landscapes vary in their adaptability to change with differing environments, composition, types of use, and significance. Landscapes can be managed for greater adaptability by redefining management parameters to overcome constraints, and by building greater diversity, redundancy, connectivity, and modularity. In other words, landscapes have both an inherent capability to adapt and an added capability through adaptive management. Adaptive techniques include compatible substitutions, alterations, and additions to the landscape that are more suited to changing conditions. Successful adaptive techniques amplify inherent adaptive processes or mimic naturally adaptive features.

NPS

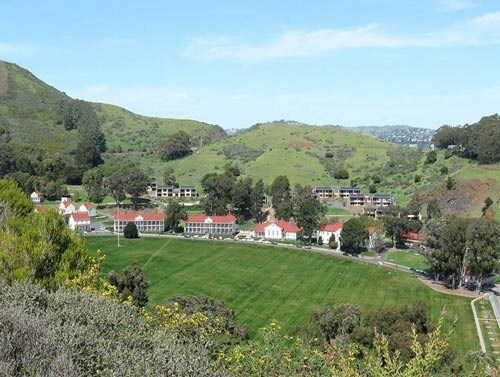

A hard fescue cultivar with high heat tolerance, Aurora Gold (Festuca trachyphylla), was ultimately selected. For three years following installation, maintenance staff used an automated irrigation system connected to an on-site weather station to establish sufficient cover. Today, only limited irrigation is used in the regular maintenance of the lawn (about 1.3 million gallons of water per year, compared to 15.5 million gallons per year for comparable areas of traditional lawn). The rehabilitated parade ground lawn also minimizes pesticide and herbicide use, resulting in a decreased risk of runoff. The growth rate of the lawn requires mowing only a few times a year during peak growing season.

NPS

The overall character of the Fort Baker parade ground is consistent with its historic appearance for nine months of each year, resulting in a rehabilitation treatment that is considered compatible. However, during the dry summer months, the lawn is allowed to go dormant, resulting in a rich golden color that is distinct from the historic conditions. This approach is a compromise that is offset by contemporary management goals to reduce water use in irrigation (by 14.2 million gallons per year), mowing time (by five hundred fifty hours per year), mower fuel use (by six hundred sixty gallons per year), pesticide use, and synthetic fertilizer use (by 4.5 tons per year).14

NPS

To protect the historic road infrastructure, which is part of the park’s National Historic Landmark District, the NPS is using naturalistically designed log structures to deflect the main channel, or thalweg, of rivers and creeks away from the toe of road embankments and to reduce the velocity of the current, allowing for deposition of sediment rather than scour along river banks. The log structures slow the current and enrich riparian habitat, emulating naturally occurring logjams that protect riverbanks from erosion. The installation of the logjams is an adaptation design that meets The Secretary of the Interior’s Standards for Rehabilitation, as the logjams are visually compatible with the naturalistic design style of the park’s roads.

Continue: Resiliency in Action at Hubbell Trading Post National Historic Site

Back to Resilient Systems Main

14. Christopher Beagan and Amy Hoke, Practicing Sustainability, Case Study: Fort Baker, National Park Service Park Cultural Landscapes Program, https://www.nps.gov/subjects/culturallandscapes/case-studies-FOBA.htm (accessed February 17, 2017); National Park Service, Cultural Landscape Report for Fort Baker (Seattle, Wash.: National Park Service, 2005).

Last updated: February 24, 2017