What do researchers want to know about bats?

Questions Researchers Ask

Find out which bat species are present in national parks.

Learn more in this article: Bats in Acadia: Facing Challenges but Hanging on

Annual survival rates and reproduction rates are indicative of a healthy population. A female bat typically only gives birth to one pup a year, so every baby bat is important and it can take a long time for bat populations to recover from a decline. Gather some of this information requires capturing bats to collect samples, determine pregnancy or identify juveniles, but valuable information can also be obtained remotely. Counting the number of bats hibernating within a cave during winter or the number of bats that emerge from a roost in summer can provide population estimates that can be repeated over many years to determine population trends. Stable or increasing populations are a sign that the population is healthy, but severe declines like those observed following arrival of WNS to North America very concerning.

Learn more about white-nose syndrome.

NPS / Chestnut

Catching and Studying Bats

-

Bat Study at Homestead

This study seeks a threatened specie and more information about how bats utilize park habitat.

- Duration:

- 6 minutes, 4 seconds

-

Bats: Tiny Creatures, Big Challenges

Although bats are small mammals, they face some large challenges. Learn more about what the National Park Service is doing to preserve bat populations in national parks.

- Duration:

- 10 minutes, 6 seconds

-

Outside Science (inside parks): Bats at Glen Canyon National Recreation Area

Follow along as our crew learns about bats in Glen Canyon National Recreation Area

- Duration:

- 3 minutes, 56 seconds

Four Methods for Catching and Studying Bats

USGS / P. Cryan

1. Mist nets

This long-legged bat is temporarily tangled in a mist net. This loose mesh is practically invisible when strung up between two poles at dusk, and bats get caught in it when they fly by. Park staff or researchers can then carefully free the bat and collect information, such as:

- the type of species or weight,

- collect samples for genetic studies or disease surveillance, or

- mark the bat with a band or other device so it can be tracked.

The bat is then released to continue its nightly activities. Bats are quick learners, so park staff and researchers have to be creative about where to set up the nets and typically can't catch the same bat twice.

NPS Photo

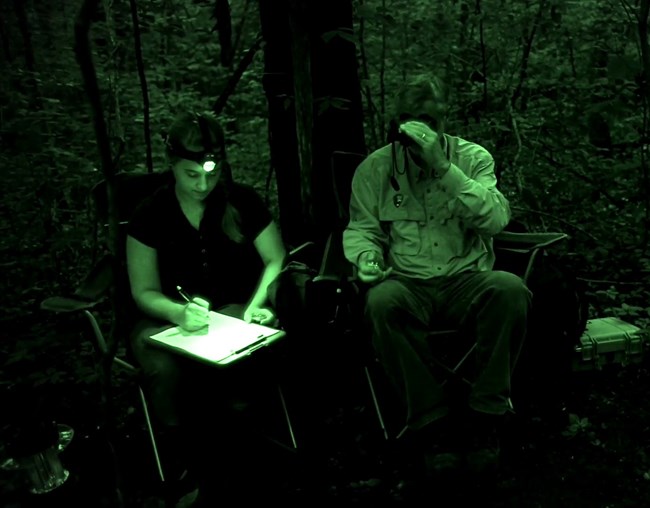

2. Field surveys

In a field survey, scientists visit locations where bats are likely to live—caves, trees, crevices, abandoned mines, etc. They are often looking for numbers and species of bats that are at these locations at different times of the year. Some special tools, like infrared cameras or telephoto lenses, can be helpful for finding and counting bats. Guano (or bat poop) samples collected at those locations can also be used to determine the bat species that use that roost.

-

Bat Surveys

Watch an evening departure of about 200 Mexican free-tailed bats (Tadarida brasiliensis) from a roost in Capitol Reef. Mexican free-tails are found in the western U.S., south through Mexico, Central America and into northern South America. Mexican free-tailed bats in Capitol Reef migrate south to Central America and Mexico during the winter. These insectivorous bats have dark brown or gray colored fur, they weigh 0.4-0.5 oz (11-14 g) and their wingspan is between 12-14 in (30-35 cm). They have broad, black, forward pointing ears, wrinkled lips, and their wings are long and narrow; they are very fast flyers. Although this roost only numbered about 200 bats, colonies of over 20,000,000 can be found elsewhere in their range!

- Duration:

- 1 minute, 5 seconds

USGS / P. Cryan

3. Radio transmitters

In some cases, researchers need to be able to track a bat to learn about the secret places that bats go to rest, hibernate or raise young. The information helps managers know where bats are during different times of the year and what locations they need to protect for the bats.

To do this, researchers attach temporary radio transmitters onto the back of a bat (like a tiny backpack) after it is captured using a net or other method. The bat is then released. Throughout the next few weeks, the researchers can find the bat and track its movements using an antenna to detect the signal that is constantly sent out from the tiny radiotransmitter on the bat. After a few weeks, the transmitter falls off and the bat can return to its secretive ways.

NPS / Veronica Verdin

4. Acoustic surveys

Scientists can record the echolocations or calls that bats make when they are flying through the air using specialized microphones and recording devices. Just like birds, different species of bats tend to make different types of sounds, which allows the researcher to identify the species of bat that flew by.

The recording device may be left in the field to record bat calls over a number of nights or can be used to survey an area in one night by walking or driving along a specific route.

Additionally, many parks have permanent monitoring stations to track bat activity year-round.

Last updated: October 24, 2024