|

The first challenge of restoring Giant Forest was to demolish and remove infrastructure without causing further damage to vegetation and soils. To achieve this goal economically and within the targeted time frame, the demolition was accomplished by contractors using heavy equipment such as excavators, loaders, and backhoes, or smaller equipment or hand tools in sensitive areas. Over 282 buildings, 24 acres of asphalt, dozens of manholes, a sewage treatment plant and spray field, and all exposed sewer and water pipe, aerial telephone and electric lines, and underground propane and fuel tanks have been removed. Ecological restoration has been conducted on 231 acres. The demolition was phased over five major projects, spanning the years 1997 to 2005. Phase 200 M (1997-1999) removed all buildings and infrastructure from the Giant Forest Lodge, and buildings in Pinewood, Highlands, and Firwood. Phase 200 O (1999) removed all buildings and infrastructure from Lower Kaweah, Upper Kaweah, and the Market area. Phase 200 P (2000) removed the asphalt roads and remaining infrastructure from the Sugar Pine, Sunset, Paradise, Highlands, and Firwood campgrounds, which were abandoned in the 1960s. Phase 200 Q (2001-2005) removed the Sherman Tree entrance road and parking lot and replaced them with a parking lot outside of the sequoia grove and a trail leading to the tree. Phase 200 R (2005) removed roads and the final parking lot in the Lodge area.

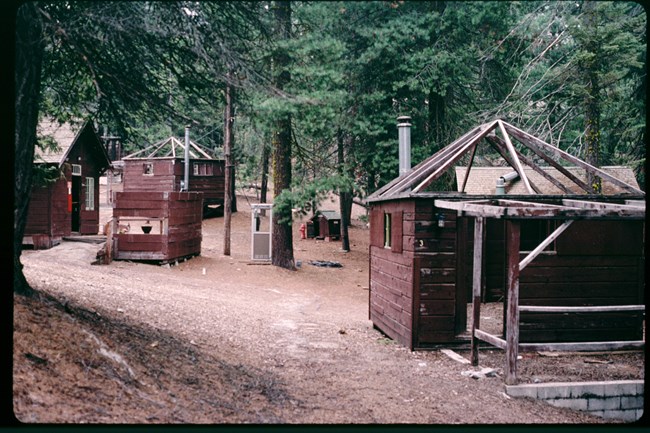

NPS photo - Athena Demetry Building RemovalMany of the buildings to be removed dated from the 1930s and contained lead-based paint and asbestos in floor coverings, wall board, pipe insulation, roofing, and other building materials. Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and mercury were present in some light fixtures. Removal and disposal of these materials had to conform to strict federal, state, and local regulations. Smaller cabins were removed by lifting the intact building off its piers with a long set of forks attached to a loader bucket. This was the preferred method, resulting in little additional soil disturbance. Heavier cabins that could not be removed by lifting with forks were often dragged with a chain fastened around the base of the building. Because equipment travel was constrained to designated routes where soils were already compact, this method also resulted in minimal soil disturbance. Sometimes chains were run through doors and windows and the building lifted with the excavator. The largest buildings were demolished in place. Buildings were moved to a central area to be broken up, and the debris either loaded directly into containers or ground into chips using a large tub grinder for transport out of the park.

NPS Photo Maintaining StructuresBy the 1990s, the sewage treatment facility in Giant Forest, known as the "Imhoff" plant (dating from the 1930s), no longer met federal and state standards for wastewater treatment. The level of treatment was substandard - "partial primary" only, with solids skimmed off and the remaining effluent heavily chlorinated and sprayed over a steep slope below the Giant Forest. The Imhoff plant had been operating on a temporary, ten-year discharge permit since 1978, and was issued a five-year extension until 1993. In 1993, the California Regional Water Quality Control Board denied renewal of the discharge permit, which would force closure of the treatment plant. The Park was required to submit a plan to comply with wastewater treatment standards by either rebuilding the plant, or providing a firm schedule for closure, with reduction of wastewater flow from the plant each year until closure.

NPS Photo - Athena Demetry Because the National Park Service had committed in 1980 to removing lodging and associated infrastructure from Giant Forest, the decision was made not to rebuild the sewage treatment plant in or immediately adjacent to Giant Forest. Construction of replacement infrastructure at Wuksachi Village had been underway since 1983, but a firm schedule for closure and removal of facilities was not in place until this denial of a discharge permit by the State of California forced the issue.

NPS photo - Athena Demetry Removing Roads and UtilitiesAsphalt pavement in roads, parking lots, and walkways was usually removed by lifting the pavement edges using the claw of an excavator or backhoe. In locations where close spacing of trees prevented use of large equipment, contractors often made use of small equipment such as Bobcats and "mini-excavators." Concrete manholes, vaults, lift stations, footings, foundations, and sewage treatment facilities were removed completely, if possible. If unacceptable vegetation or soil damage would result from complete removal, or if complete removal was prohibitively expensive, the concrete was removed to at least 2 feet below the surface. Any remaining concrete was fractured prior to backfilling to allow water to drain through. Concrete utilities were removed by excavators and backhoes, but in locations not accessible to this equipment, such as the sewer line running beside Deer Creek, concrete was broken up using a jackhammer and hauled away by mules. All asphalt and concrete debris was recycled by crushing into ¾ inch chunks for use as road base in future construction projects. To protect shallow roots, underground water and sewer lines were left in place unless portions were exposed during demolition. In such cases, pipes were removed until remaining portions were 2 feet below the surface. Pipes were removed by pulling horizontally rather than by digging and lifting. Ends of pipes to be left in place were plugged with concrete to prevent channeling of groundwater. Underground propane tanks were purged of any remaining propane and removed completely. Where telephone lines, electric lines, or light fixtures were attached to live trees, the connecting brackets were removed completely, if possible. If the tree had grown around the bracket to such an extent that removal would injure the tree, protruding parts were cut flush with the tree and the remainder left in place. In most cases contractors were able to remove the entire fixture.

NPS photo - Athena Demetry Protecting the ForestTo protect soils and vegetation, contractors were required to install fencing around sensitive sites and residual vegetation before beginning demolition. Eight-foot tall lumber barricades were placed around mature sequoias to protect the soft bark from damage and to keep equipment from disturbing roots or compacting soils close to the base of the trees. Four-foot tall orange fencing was installed around groupings of trees, shallow root zones, or other sensitive areas. Lath snow fence was wrapped around boles of trees in close proximity to buildings to prevent mechanical damage to bark during removal. Metal sheeting was placed over exposed or shallow sequoia root zones to disperse equipment weight and prevent wheel damage to roots. Travel routes were designated on contract drawings to constrain equipment travel and minimize soil compaction. Incentive for protecting natural resources was supplied by a contract provision by which the contractor could be assessed monetary damages for causing injury to trees, soils, or vegetation. NPS inspectors and a restoration ecologist provided daily oversight of operations. Also prior to demolition, silt fence or excelsior (curled aspen fiber) filter logs were installed in locations where water runoff exits the project site to prevent silt input to streams or wetlands.

NPS photo - Athena Demetry. Changing ValuesLarge, old trees may contain rot at their bases or other defects that increase their probability of falling and endangering human safety and property. Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks conduct a hazard tree surveillance and mitigation program to protect human safety and property in developed areas. |

Last updated: October 3, 2023