The following excerpt is from To Heal the Wounded Nation's Life: African Americans and the Robert Gould Shaw/54th Regiment Memorial (2021) by Kathryn Grover. This Special History Study was commissioned by the National Park Service to examine “African Americans’ involvement in, reactions to, and uses of the Robert Gould Shaw/54th Regiment Memorial, unveiled on Boston Common on 31 May 1897.” > The publication is available for download in its entirety. The idea for a sculpted memorial to Shaw emerged soon after his death at Fort Wagner on Morris Island near Charleston, South Carolina, on 18 July 1863, and all accounts maintain that the notion originated with Joshua Bowen Smith (1813-79), an African American caterer who had been living in Boston since about 1835. Smith, never candid about his place of birth, was very likely born in slavery, but little is documented about his early life. He may have been orphaned as a young teenager, and he was working in domestic service by the early 1830s. “In those days,” he recalled much later, “I was a servant in a family traveling through the South. They stopped in Washington, and I there saw for the first time, men, women and children sold on the auction block as cattle are sold.” One evening he waited on the family while they were dining at a place in “the country” and witnessed an African American girl being whipped and asking God for mercy. “It was the first prayer I had ever heard,” Smith said, “and there I swore eternal hatred to slavery.” Smith’s first job in Boston was probably waiting table at the Mount Washington House, a large but short-lived hotel in South Boston, and he is there said to have met Robert Gould Shaw’s father Francis George Shaw. He then served, and may briefly have lived, in the home of Francis and Sarah Blake Sturgis Shaw on Bowdoin Street, on the east edge of the African American West End. He met Charles Sumner, then a young attorney, while working for the Shaws, and over time the two became friends. Smith, though not one for correspondence generally, wrote to Sumner in 1851 after he left Boston to serve in the United States Senate, and as Sumner’s public advocacy of racial equality grew more steadfast and less susceptible of compromise Smith came almost to idolize him. The fact that in the 1870s he moved freely in the world and heard “no word of insult” was due entirely to Sumner, Smith declared in an address to the state legislature after the senator’s death: I have lived out two generations, and have tasted the bitter fruit of the seed planted by our fathers eighty years ago. I have had the doors of the church and the State House shut in my face but I have lived to enjoy the blessings of liberty and to-day I stand the peer of every man in this House, and this, as I believe, through the life and labors of Charles Sumner….Five and twenty years ago the anti-slavery sentiment of New England fixed upon Sumner as the man to go to Washington to strike the first blow. You speak of Sherman’s march from Atlanta to the sea as a great victory. But that was nothing compared to the success of Sumner. Sherman had the nation at his back. Sumner had simple justice. Sherman had a hundred thousand men. Sumner fought single-handed and alone. Sherman had the wealth of the nation laid at his feet, and Sumner had only the prayers of the poor. 1 Because their lives told the story of American compromise, large and small, over and over, African American Bostonians valued above all else Sumner’s refusal to circumscribe in any way the legal achievement of racial equality. African American men hesitated to enlist Regiment of Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry, the first federally authorized African American regiment raised in the North, because the federal War Department refused to commission African American officers. But the abolitionist Wendell Phillips argued that if they did not enlist African American commissions would never be realized. “If you cannot have a whole loaf,” he asked them, “will you not take a slice?” Even Frederick Douglass, who complained often about the North’s “accommodation and truckling” to the South and was as dismayed as anyone by the War Department’s position, asserted that blacks must join the Union forces “by any door open to him, no matter how narrow.”

The men who accepted these arguments and enlisted in the 54th served with fidelity even as racism confronted them everywhere—in the fight for equal pay, in their consignment to fatigue duty, in blatant hostility to them during and immediately after the war, in the federal refusal to promote from within the ranks. For their officers, one 54th sergeant wrote to African American Bostonian William Cooper Nell in August 1864, “We want men whose hearts are truly loyal to the rights of man” instead of “a crowd of incompetent civilians and non-commissioned officers of other regiments” sent to take the place of officers killed or wounded. The sergeant cited Boston’s Irish American newspaper and its regular racist vitriol and asked Nell how African American troops could “have confidence in officers who read the Boston Courier and talk about ‘Niggers?’” Not until the fall of 1864 were African American soldiers paid their due. Not until early in 1865 did a handful of African Americans of the 54th and 55th earn commissions. And not until 1948 were the United States armed forces desegregated.2 As soon as Shaw fell on the parapet at Fort Wagner and was buried in a trench with his men, Joshua Bowen Smith suggested to Sumner that a monument be erected to Shaw. About the same time Brigadier General Rufus Saxton, the son of western Massachusetts abolitionists and the military governor of South Carolina, proposed that African Americans pledge “the first proceeds of your labor as freemen” to creating such a monument on the Morris Island ruins of the fort. Addressed to both soldiers and “freedmen” in the Army’s Department of the South, Saxton’s letter did not address the fact that the soldiers had not yet been paid. In Boston Sumner urged Smith to hold off on the monument idea until the war was over; in South Carolina concern emerged that the proposed site was unstable and in hostile territory. James Henry Gooding, a corporal in the 54th, may have been the first to articulate the singular folly of a South Carolina monument, and he might have done much to propel the movement for a Boston monument to his colonel and his regiment. Yet Gooding did not return with his regiment: he was wounded and captured at the Battle of Olustee and died at the Confederacy’s Andersonville prison in July 1864.3 Evidence suggests that Joshua Bowen Smith almost single-handedly began to raise funds for the monument after Massachusetts Governor John Albion Andrew convened a meeting of Bostonians interested in the idea. Though African American Baptist minister Leonard Grimes attended the meeting, neither he nor any of the ten white Bostonians appointed to a committee to raise funds for it are cited as having done so; Smith was in fact not named to that committee. Edward Atkinson, the committee’s treasurer, disliked the idea of soliciting funds at all, but he noted that Smith had himself pledged five hundred dollars and received pledges from other African Americans. The Boston Transcript reported that an unnamed “colored association of 800 members” was expected to contribute to the fund as well. Joshua Bowen Smith, owed money for provisioning a white Massachusetts regiment during the war, died in straitened circumstances in 1879, and with his death what pledges or actual contributions African Americans had made to the memorial disappeared from the record. When Sumner first publicly advocated a monument in the fall of 1865, he spoke as much of the 54th as he did of Shaw. Shaw had “turned away from all the blandishments of life to consecrate himself to his country”; his regiment had similarly consecrated itself “to the redemption of a race.” He declared that Fort Wagner was the African American soldiers’ Bunker Hill: “Though defeated, they were yet victorious. The regiment was driven back, but the cause was advanced. The country learned to know colored troops and they learned to know themselves. From that day of conflict nobody doubted their capacity or courage as soldiers.”4 Still, in his mind’s eye Sumner, and apparently Joshua Bowen Smith, saw only Shaw on a horse, not Shaw with his regiment, even as the Shaw family urged a more inclusive conception. And still, in conflict after conflict, the government and the public at large continued to doubt the capacity and courage of African American men as soldiers. Almost as soon as the war ended African Americans suspected that the cause of equal rights might not advance. Connecticut, Wisconsin, and Minnesota had refused the elective franchise to African American men, and widespread racial hostility in the South impelled New England African Americans to meet in Boston in December 1865. The convention resolved to send a delegation to Congress so that its actions “may not give ‘color to the idea that black men have no rights that white men are bound to respect.’” It affirmed that until all Americans without regard to color enjoyed equality before the law “there will be kept up an agitation, a conflict as intense, as wide-spread, and as all-absorbing as that which marked the history of the anti-slavery warfare, which will materially affect all the material interests of the land.”5 Though that was not quite to be, hope strengthened when the nation ratified the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments, federal Reconstruction promised to promote and protect African American rights in the South, and Congress passed the Equal Rights Act of 1875, shortly after Sumner’s death. In historic terms, however, those achievements were ephemeral. As early as 1866 Harriet Jacobs, former fugitive, freed people’s aid worker, and author, told Lydia Maria Child of the vast betrayal already underway in the South: Don’t believe the stories so often repeated that the negroes are not willing to work. They are generally more than willing to work, if they can get anything for it. But the ex-slaveholders try to drive such hard bargains with them, it is no wonder they sometimes refuse to sign the contracts. Some of the planters propose to the freedmen to raise a crop of rice, corn, and cotton, and give them two-thirds of the crop, paying for their own rations, clothing, and doctor’s bills out of the remaining third, which has to be divided between seventy or a hundred laborers. One of these laborers told me that, after working hard all the season to raise the master’s crop, the share he received of the profits was only one dollar and fifty cents….I visited some of the plantations, and I was rejoiced to see such a field of profitable labor opened for these poor people. If they could have worked these lands for two years, they would have needed no help from any one. But just as they were beginning to realize the blessings of freedom, all their hopes were dashed to the ground. President Johnson has pardoned their old masters, and the poor loyal freedmen are driven of the soil, that it may be given back to traitors. These masters try every means in their power to make the condition of the freed people worse than it was in slavery, if possible. I am in hopes that something will yet be done for them by Congress.6

In 1872 Congress passed, and President Ulysses S. Grant signed, the Amnesty Act restoring the right to vote and hold office to all but five hundred Confederate officers, thus nullifying Section 3 of the Fourteenth Amendment; all but Jefferson Davis were restored to full citizenship four years later. “If the officers and men who did the fighting on the Union side from 1861 to 1865 could have foreseen that in 1879 the Confederates would have a majority in both branches of Congress,” the Boston Journal noted that year, “it would have been pretty hard to prevent them from stacking arms and quitting the service.”7 In 1877 Grant’s successor Rutherford B. Hayes withdrew federal troops from the South, essentially turning the government’s back on its promise of protection to African Americans as they voted and attempted to lead lives unaffected by terrorism. And in 1883 the United States Supreme Court declared the 1875 Civil Rights Act unconstitutional. Compromise again seized hold of the government. Chester Alan Arthur continued what Hayes began by appointing former rebels to federal jobs with the expectation that, as Frederick Douglass stated, “this conciliation policy would arrest the hand of violence, put a stop to outrage and murder, and restore peace and prosperity to the rebel States.” In his third and last autobiography, published late in 1892, Douglass wrote that the administration of Hayes was “to the loyal colored citizen, full of darkness and dismal terror” exceeded only by the administration of Arthur, whose “indulgence, indifference, and neglect of opportunity, allowed the country to drift (like an oarless boat in the rapids) toward the howling chasm of the slaveholding Democracy.” Douglass stated, “The sentiment that gave us a reconstructed Union on a basis of liberty for all people was blasted as a flower is blasted by a killing frost….When the Republican party ceased to care for and protect its Southern allies, and sought the smiles of the Southern negro murderers, it shocked, disgusted, and drove away its best friends.”8 In 1899 African Americans in Massachusetts sent an open letter to President William McKinley reproaching him for his “incomprehensible silence” as African Americans “everywhere throughout the South” found their rights denied, “violently wrested from us by mobs, by lawless legislatures, and nullifying conventions, combinations, and conspiracies, openly, defiantly, under your eyes, in your constructive and actual presence.” McKinley, they asserted, sought to expel Spain from Cuba in the espoused interest of freedom and independence for Cubans as he turned a blind eye to injustice in his own country:

The struggle of the negro to rise out of his ignorance, his poverty and his social degradation . . . to the full stature of his American citizenship, has been met everywhere in the South by the active ill-will and determined race-hatred and opposition of the white people in that section. Turn where he will, he encounters this cruel and implacable spirit. He dare not speak openly the thoughts which rise in his breast. He has wrongs such as have never in modern times been inflicted on a people, and yet he must be dumb in the midst of a nation which prates loudly of democracy and humanity, boasts itself the champion of oppressed peoples abroad, while it looks on indifferent, apathetic, at appalling enormities and iniquities at home, where the victims are black and the criminals white.9

By the 1890s a younger generation of African Americans in Boston, many of them born in the South and a good share of them veterans of the Massachusetts regiments, had begun to fight independently and through both major political parties to lobby all levels of government to stop the massive violation of African American rights everywhere. African American attorney James H. Wolf, a Civil War Navy veteran, was among those who signed the letter to McKinley; so did Isaiah D. Barnett, who served in the 41st United States Colored Troops. Charles Lewis Mitchell, a native of Hartford, Connecticut, may have been among the “others” who signed the letter but whose names were not printed with it. Mitchell was a printer who had worked for Garrison at the Liberator before he enlisted in the 55th Regiment four days before the attack on Fort Wagner. In 1864 he had been detailed to serve as the post printer at Morris Island, but when he learned that the 55th would take part in an expedition designed to cut the Charleston and Savannah Railroad of in order to aid General William T. Sherman’s march to the sea, he asked to return to his regiment. At Honey Hill Union forces came across Confederate forces blocking the road, and in the fighting that ensued most of Mitchell’s right foot was blown of and the ankle damaged; the lower third of his leg was later amputated. One account in Colored American Magazine noted that as Mitchell was being carried away from the field on a stretcher, he rose up as his lieutenant colonel passed, “saluted and cheered him, and bade him ‘go ahead.’” Near the end of the war Mitchell also succeeded in capturing two Confederate cannons (“Napoleon guns”) during the siege of Charleston. His actions at Honey Hill earned him the rank of second lieutenant in 1865. Mitchell was one of the few African American soldiers to receive an officer’s commission during the war, though because of his disability he was never mustered in at that rank.

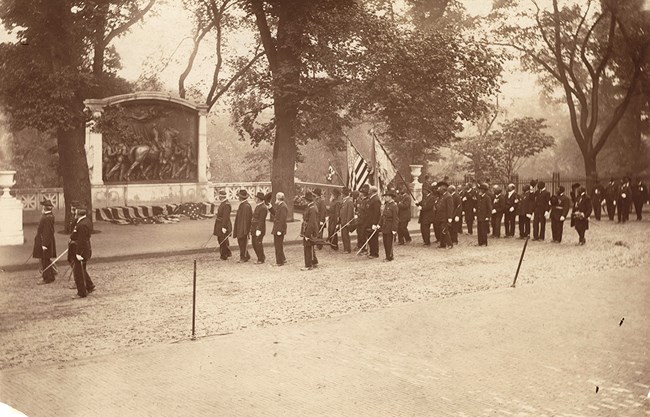

After the war Charles Mitchell returned to Boston with “that added grace, the halting which is the stateliest step of the soldier,” as Wendell Phillips put it, and began his forty-four-year career at the Boston Custom House, where he was for some time a respected statistician. In 1866 Mitchell ran successfully for the state legislature; he and Edwin Garrison Walker, the son of antebellum activist David Walker, were the first two African Americans elected to that body. “These men are chosen, not as a joke or a satire, but in honest earnest, because they are ft for the position,” the Berkshire County Eagle asserted, “and because they have rights which white men at last respect.”10 Mitchell was marshal of the procession at Sumner’s funeral and printed the proceedings of the memorial meeting held in Boston for the late senator. He and Lewis Hayden were among the pallbearers at Garrison’s funeral five years later. And he was president of the Wendell Phillips Club, one of the Boston’s main African American political associations. Mitchell was present at virtually all of the postwar political gatherings of African American Bostonians, and he spoke at an 1899 meeting protesting the lynching of African Americans in the South. Charles L. Mitchell was also an avid participant in many of the reunions of the Massachusetts African American regiments. He helped organize the earliest ones and managed the more formidable effort to locate veterans for the Shaw Memorial unveiling procession; Mitchell was one of Norwood P. Hallowell’s five African American aides in that parade. He was also committed to Company L of the 6th Massachusetts Regiment, formed in 1878 from Companies A and B of the 2d Battalion of Massachusetts Volunteer Militia. He had spent the last three afternoons of the regiment’s stay at its South Framingham training camp with the men, and he followed them on foot to the train station as they left for the front. This walk at a military pace strained Mitchell’s Civil War wound, already exacerbated by his effort some time earlier to save his wife when her clothing caught fire as she cleaned gas lamps in their home. Mitchell had worn a prosthetic for years after the war, but these two events made it necessary to amputate the leg entirely, in the summer of 1898. While the company served in Cuba in 1898 Mitchell created a fund to support the soldiers’ wives and children, and when men in Company L won commissions as officers Mitchell declared he had at last been compensated “for leaving a leg in South Carolina in the Civil War.” 11 When he died, Mitchell warranted a four-paragraph obituary in the Boston Globe and one paragraph in the Herald, and for all his activism and dedication he is scarcely remembered today. With the notable exception of William H. Carney, all of the African Americans of the 54th and 55th Regiments lived and died in far greater obscurity than Mitchell did. But while they lived untold numbers of them returned to Boston on Memorial Day or the dual anniversary of Shaw’s death and the Fort Wagner assault to congregate at the Shaw Memorial. Just as American educator and diarist Charlotte Forten thought of Robert Gould Shaw as “our colonel, ours especially,” by some silent agreement the Shaw Memorial became for African American veterans their memorial.12 They came to see each other again at the Shaw Memorial. There they relived their wartime strife and camaraderie and shared what they believed their service had and had not accomplished for African Americans generally. Frances Ellen Watkins Harper asserted in the fall of 1863 that those of the 54th who had fallen at Fort Wagner had died “not in vain / Amid those hours of fearful strife; / Each dying heart poured out a balm to heal the wounded nation’s life.” The memorial itself symbolized and may have acted as such a balm at particular historical points. Art historian Kirk Savage has argued that public monuments “are the most conservative of commemorative forms precisely because they are meant to last, unchanged, forever. While other things come and go, are lost and forgotten, the monument is supposed to remain a fixed point, stabilizing both the physical and the cognitive landscape.” But while the Shaw stands physically now as it did then, the cognitive landscape around it has often shifted. Because it depicts a moment of interracial unity, the Shaw Memorial became a touchstone for protests of school segregation, wage discrimination, continued racial animus, even the Kent State massacre and the Vietnam War. And as Americans celebrated Shaw, the regiment, and the memorial itself, African Americans particularly must from time to time have seen it much as Booker T. Washington did when he stated in 1897 that it stood “for effort, not victory complete.” Very nearly a century later, the Rev. Peter J. Gomes cited Booker T. Washington’s statement when he spoke at the memorial’s rededication. By its very presence, Gomes declared, the Shaw Memorial continues to mark “how far it is we have to go until black and white can live side by side, and in peace.” 1. “Speech of Joshua B. Smith before the Legislature of Massachusetts,” Boston Journal, 11 March 1875. Smith’s varying reports of birthplace to census takers and clerks—Coatesville, PA; Virginia; the District of Columbia; even “unknown” in the 1850 census—is a prevarication that frequently connotes fugitive status, and Smith himself seemed to declare, sometimes obliquely, his onetime enslaved status on several occasions. In “Declaration of Sentiments of the Colored Citizens of Boston on the Fugitive Slave Bill,” Liberator, 11 October 1850, 2, Smith’s statement during a meeting protesting the just-passed Fugitive Slave Act was paraphrased: “He advised every fugitive to arm himself with a revolver—if he could not buy one otherwise, to sell his coat for that purpose. As for himself, and he thus exhorted others, he should be kind and courteous to all, even the slave-dealer, until the moment of an attack upon his liberty. He would not be taken ALIVE, but upon the slave-catcher’s head be the consequences. When he could not live here in Boston, a FREEMAN, in the language of Socrates, ‘He had lived long enough.’” After Sumner’s death in 1874, a time no longer dangerous for fugitives, the Boston Globe paraphrased Smith’s address at a mass meeting: “Mr. Smith spoke of the time when he emerged from slavery into the world’s cold atmosphere, like a chrysalis prematurely launched into an air too chill for its winged existence” until Sumner began to work on behalf of enslaved Americans. See “The City’s Mourning,” Boston Globe, 16 March 1874, 1, 2. Robert T. Teamoh, Sketch of the Life and Death of Col. Robert Gould Shaw (Cambridge, MA: Grandison & Son for the author, 1904), 11, stated that Smith was “an escaped slave”; it is likely that Teamoh knew Smith personally. “Obituary. Joshua B. Smith,” Boston Post, 7 July 1879, 3, states that Smith was a servant of John C. Craig, which whom he traveled in the South; “J. B. Smith Dead: The Career of Boston’s Well-Known Colored Caterer,” Boston Herald, 5 July 1879, 1, mentions Craig by last name only. “Idea of a Colored Man: Joshua Benton [sic] Smith, a Warm Admirer of Col Shaw, First to Suggest an Equestrian Memorial,” Boston Globe, 31 May 1897, 7, states that Smith “escaped from slavery in Virginia” and implies that he escaped during his travels with Craig. Only two men bearing this name have been identified in early censuses and newspapers. One John C. Craig owned numerous horses at his estate in the Roxborough district of Philadelphia and raced them avidly. He died in 1837 at the age of 35 while traveling abroad; slavery was illegal in Pennsylvania by the 1830s, which would indicate that Smith, if working for this John C. Craig, was employed and not enslaved by him. And given that Smith often claimed to be from Pennsylvania, this Craig is the more likely to have been the man for whom he worked. The other, John Cofey Craig, was born in 1793 in Lancaster County, SC, moved to Lincoln County, TN, about 1826, listed two enslaved people in his household in 1830, and moved to Tippan County, MS, about 1836; he owned more than 1000 acres in Mississippi before he died in 1882. The Mount Washington House became the second home of the Perkins Institute and Massachusetts Association for the Blind in 1839. 2. Douglass quoted in James M. McPherson, The Negro’s Civil War: How American Blacks Felt and Acted during the War for the Union (1965; reprint, New York: Ballantine Books, 1991), 9. The letter to Nell appeared in the Liberator, 4 October 1864. 3. James H. Gooding was born in 1837, possibly in Troy, NY, and was in New Bedford by 1856, when he shipped out on the whaling vessel Sunbeam. He served on the crew of one more whaling voyage and a trading voyage before he enlisted on 14 February 1863 in the 54th; he was the eighth man from New Bedford to do so. Gooding’s letters to the New-Bedford Mercury were published nearly every week between 3 March 1863 and 22 February 1864 and have been reprinted and annotated in Virginia Matzke Adams, ed., On the Altar of Freedom: A Black Soldier’s Civil War Letters from the Front: Corporal James Henry Gooding (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1991). 4. “S.,” “Monument to Colonel Shaw,” Boston Daily Advertiser, 2 October 1865, 2, and Liberator, 22 December 1865, 2; the latter identified the author as Sumner. 5. “The New England Convention of Colored Citizens,” Anglo-African, 23 December 1865. The quoted section within the quote was from U.S. Supreme Court Chief Justice Roger B. Taney’s 1857 decision in Dred Scott v. Sanford, which asserted that because Scott was enslaved he was not a citizen and had no right to file suit in a federal court. 6. Harriet Jacobs to Lydia Maria Child, quoted in The Independent (New York), 5 April 1866, and transcribed in Jean Fagan Yellin et al., eds., The Harriet Jacobs Family Papers (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2008), 2: 663–64. 7. Boston Journal quoted in Heather Cox Richardson, The Death of Reconstruction: Race, Labor, and Politics in the Post-Civil War North, 1865-1901 (Cambridge, MA, and London: Harvard University Press, 2001), 159. 8. Frederick Douglass, Life and Times of Frederick Douglass Written by Himself (1893) in Frederick Douglass: Autobiographies (New York: Library of America, 1994), 963–64. 9. Open Letter to President McKinley by Colored People of Massachusetts (3 October 1899), Daniel Murray Pamphlet Collection, Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/resource/lcrbmrp.t1722/?sp= 14&r=-0.854,0.536,2.707,1.444,0. 10. Berkshire County Eagle, 8 November 1866, 2; Phillips quoted in “Mr. Charles L. Mitchell,” Colored American, 20 October 1900, 6. 11. This last statement appears in Anthony W. Neal, “Captain William J. Williams,” Bay State Banner, 7 August 2015, https://www.baystatebanner.com/2015/08/07/captain-william-j-williams-lawyer-war-veteran-frst-african-american-elected-to-the-chelsea-board-of-aldermen/. On this incident in Mitchell’s life see “Colored Veteran was Loyal,” Boston Globe, 28 June 1898, 12, and “Distress of Soldiers’ Wives,” Boston Globe, 8 August 1898, 5. Other background on Mitchell appears in “Famous Negro Fighters,” Leslie’s Weekly Illustrated, 23 June 1898, 407; “First Colored Company,” Boston Globe, 17 May 1898, 5; “Honors for Colored Soldiers,” ibid., 16 May 1898, 12; “Mr. Charles L. Mitchell,” Colored American, 20 October 1900, 6; and “Charles L. Mitchell,” The Crisis, July 1912, 118-19. See also Appendix C. 12. Charlotte Forten, diary entry for 20 July 1863, in Brenda Stevenson, ed., The Journals of Charlotte Forten (New York: Oxford Press, 1988), 494. ► Back to Voices of the Shaw/54th Memorial page

|

Last updated: February 2, 2022