NPS The grand scenery of Rocky Mountain National Park is the product of a complex geologic history spanning almost two billion years. The area occupied by the park has been repeatedly uplifted and eroded. Although many of its mountaintops have been flattened by ancient erosion, recent glaciation has left steep scars, U-shaped valleys, lakes and moraine deposits

NPS The BeginningThe park's oldest rocks were produced when plate movements subjected sea sediments to intense pressure and heat. The resulting metamorphic rocks (schist and gneiss) are estimated to be 1.8 billion years old. Later, large intrusions of hot magma finally cooled about 1.4 billion years ago to form a core of crystalline igneous rock (mostly granite). Paleozoic EraDuring the long Paleozoic Era, the park area frequently submerged, lifted up and eroded. Mesozoic EraEarly in the Mesozoic Era, approximately 100 million years ago, dinosaurs roamed the shoreline of a shallow sea which extended from the Gulf of America to the Arctic Ocean. Animal remains were deposited in layers of sand, silt and mud. The resulting sedimentary rock layers (including fossils) are now exposed in the foothills to the east of the park.

NPS Almost 70 million years ago, the Rocky Mountain uplift began. Giant blocks of ancient crystalline rock, overlain by younger sedimentary rock, broke and were thrust upward. Even as the uplift occurred, streams started eroding away the sedimentary rocks and washed new sediments to the east and west. When the sedimentary rocks were almost gone, erosion continued leveling the ancient Precambrian rocks until only a few isolated remnants projected above the gently rolling landscape. The gentle slopes atop Trail Ridge and Flattop Mountain are remnants of this erosion surface.

NPS Cenozoic EraDuring the Cenozoic Era, some faulting and regional up-warping lifted the Rocky Mountain Front Range as much as 5,000 feet to it's present height. Some volcanic activity left young volcanic rock in contact with Precambrian rocks. The volcanic rocks are seen mostly on the west side of the park. Glacial PeriodDifferential movement along faults disrupted drainage patterns, resulting in higher mountains, waterfalls and large valley areas such as Estes Valley. Streams had established drainage patterns with V-shaped valleys cut into hard rock before the climate became cooler, perhaps two million years ago. In the higher valleys, snow packed into glacial ice which flowed down the valleys. Glacial erosion changed V-shaped valleys into U-shaped valleys. The converging rivers of ice flowed down into lower valleys where the ice warmed, melted and dropped the debris it had scraped from the mountainsides above. Loose rock material carried by the ice deposited along the sides, forming lateral moraines. At the ends of the glaciers, rocks piled up into terminal moraines. Although glaciers must have filled high valleys and then melted at least four different times, only the latest two times (Pinedale and Bull Lake) left evidence easy to find. During the last major glaciation period, glaciers from Forest Canyon, Spruce Canyon, Odessa Gorge and numerous tributary valleys all flowed together and melted in the area now called Moraine Park. This glacier deposited lateral moraines along the south and north sides of Moraine Park and a terminal moraine against Eagle Cliff mountain to the east. Similar glaciers were melting in areas now called Glacier Basin, Horseshoe Park and Kawuneeche Valley.

NPS/Crystal Brindle Today, steep semicircular scars called cirques indicate the top of U-shaped glaciated valleys. Chasm Lake lies in a cirque below the east face of Longs Peak. A cirque on Sundance Mountain is easily seen from Trail Ridge Road and numerous cirques may be seen from Bear Lake Road. Glacial erosion also left scratches, grooves and polished surfaces on some of the rocks.

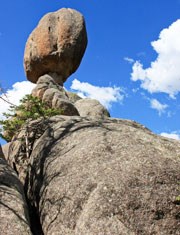

NPS The few small glaciers and snowfields now occupying the tops of glacial valleys are only hints of what the ice age was like. The park's high mountaintops were not covered with glacial ice and a few of the lower valley areas of the park escaped the effects of glaciation. For example, the Twin Owls and Gem Lake Trail area of Lumpy Ridge feature coarse-grained granite rounded into interesting shapes by millions of years of non-glacial erosion. Outside the park, water from melting glaciers helped carve canyons to the east. Hogback ridges were left near the Colorado Front Range cities of Loveland and Lyons by differential erosion of sedimentary rock tilted up against older crystalline rock of the mountains. Rocky Mountain National Park occupies only a small part of the 200-mile long Front Range of the Rocky Mountains, but this part of the Continental Divide shows the effects of ancient erosion and many of the valleys illustrate classic features of glaciation. |

An official website of the United States government

Here's how you know

Official websites use .gov

A

.gov website belongs to an official government

organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS

A

lock (

) or https:// means you've safely connected to

the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official,

secure websites.