|

Wildland fire managers today understand the important role fire plays in an ecosystem’s health, but management practices have evolved to reach today’s policies. Fourteen years later Captain Moses Harris, Troop M, First US Cavalry took command of Yellowstone. These men began fighting fires throughout the park, making them the nation’s first paid wildland firefighters. Yellowstone started making regulations to reduce wildfires, including only allowing camping in specific areas. Today, designated campgrounds are commonplace in National Parks. The goals and methods of wildland firefighters have been evolving ever since.

NPS Photo For decades wildland fires were thought of as catastrophic events, regardless of their cause. Efforts to suppress all fires were in line with the House Committee on Yellowstone National Park’s statement that “the most important duty of the Superintendent… is to protect the forest from fire and ax” (1885). It was not until the 1960s that the National Park Service began to change their policies from “fire control” to “fire management.” The Wilderness Act of 1964 and subsequent change in NPS policy in 1968 encouraged wildland fire use. Fires that were not threatening people or surrounding communities would be allowed to burn to help restore fire-adapted ecosystems.

Today, extensive fuels treatments are done in Rocky to create safer places for firefighters to manage fires. These treatments make fire suppression on the park's borders more effective, allowing firefighters to utilize wildland fire within park boundaries while aiming to keep the fire from escaping to nearby communities.

Wildland Fire in RockyFires are not uncommon in the park. Lightning may cause several fires a year, which may only burn a few acres before extinguishing naturally or being put out if necessary. Some fires, on the other hand, require significant effort by firefighters and can deeply impact surrounding communities.

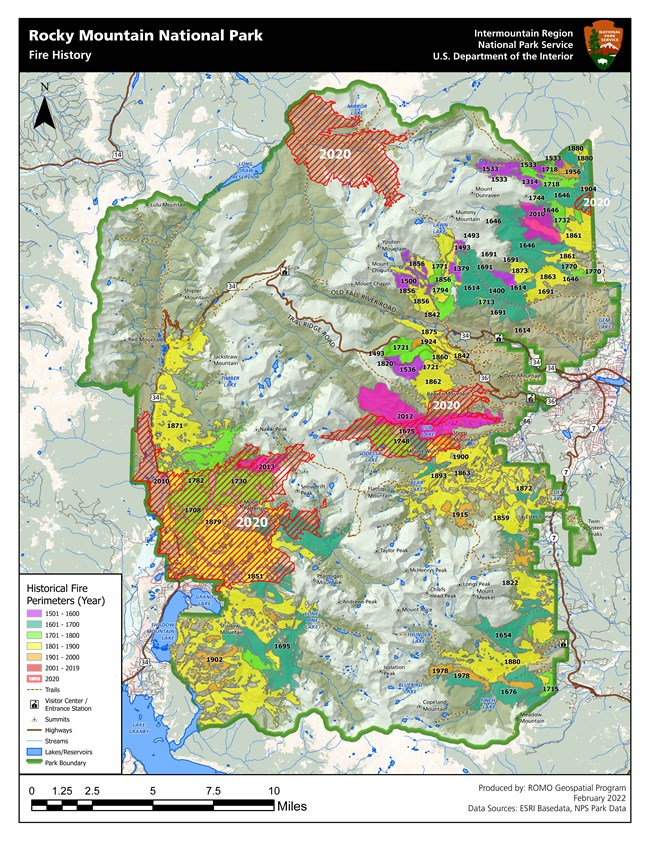

NPS Photo Bear Lake Fire, 1900In 1900, a group of picnickers next to Bear Lake built a campfire to make a pot of coffee. Although they attempted to extinguish the fire, a log continued to smolder after they left. As the winds picked up, the log and surrounding vegetation went up in flames. The Bear Lake Fire, sometimes called the "Big Fire," raged for two months, consuming the Bear Lake area.

NPS Photo Ouzel Fire, 1978The Ouzel Fire, started by a lightning strike in the Wild Basin area on August 9, 1978, is one of Rocky’s earliest examples of wildland fire use. The fire was allowed to burn under careful monitoring and, in the beginning, behaved as expected. However, strong winds in late August and early September caused the fire to spread quickly. Park managers began suppression efforts when the fire became more threatening to the public. With the help of rain and snow, the fire was contained by September 11. Then, on September 15, strong winds again set the fire into motion. The fire was pushed eastward towards the community of Allenspark. About 500 firefighters were able to stop the 1,050-acre fire from escaping the park boundary.

NPS Photo Fern Lake Fire, 2012The Fern Lake Fire started in Rocky from an illegal campfire on October 9, 2012, in steep and rugged Forest Canyon. From the beginning, fire managers knew this fire was going to be a long-term event. The high winds, steep terrain, and beetle-killed trees posed danger to firefighters, meaning there was limited opportunity to fight the fire from the ground. Firefighters from across the country battled this fire for two months. This high-elevation winter fire was unprecedented in park history. Large fires at high elevations of the Rocky Mountains are infrequent and have the potential for high consequences. Due to climatic factors and inaccessibility, Forest Canyon had not experienced a fire for at least 800 years before the Fern Lake Fire. A long-term drought had left fuels tinder-dry and, in some areas, the layer of dead and down exceeded twenty-foot depths. Mountain pine beetles had killed half the trees in the canyon, with every compromised tree posing a hazard for firefighters. The typically windy conditions in the canyon only increased the danger. On the night of November 30 and the early morning of December 1, strong winds pushed the fire more than three miles in thirty-five minutes, prompting evacuation orders of nearby community members and park employees. Through careful planning and rapid action, firefighters successfully prevented the fire from progressing across Bear Lake Road and leaving the park. The nearly 3,500-acre blaze was temporarily halted by an early December snowstorm. The last time smoke was seen on the Fern Lake Fire was January 7.

NPS Photo/ K. Grossman Cameron Peak and East Troublesome Fires, 2020In Fall 2020, Colorado saw the two largest wildfires in state history: The Cameron Peak Fire and The East Troublesome Fire. While the bulk of these fires were on lands surrounding Rocky Mountain National Park, nearly 30,000 acres - or 9% of lands - burned within the park’s boundary. On Wednesday, October 21, the East Troublesome Fire ran approximately 18 miles before it moved into the west side of Rocky Mountain National Park. It then spotted approximately 1.5 miles from the head of Tonahutu Creek on the west side of the Continental Divide to the head of Spruce Creek on the east side of the Continental Divide. Rapid evacuations took place in Grand Lake on October 21. Evacuations for the majority of the Estes Valley were implemented on October 22, as weather predictions forecast major winds on the night of October 23 through October 24 pushing the fire further to the east. Firefighting actions and favorable weather on October 24 and 25 helped halt the major movement of the East Troublesome and Cameron Peak Fires. Learn More about the 2020 Fires Here

|

Last updated: January 15, 2025