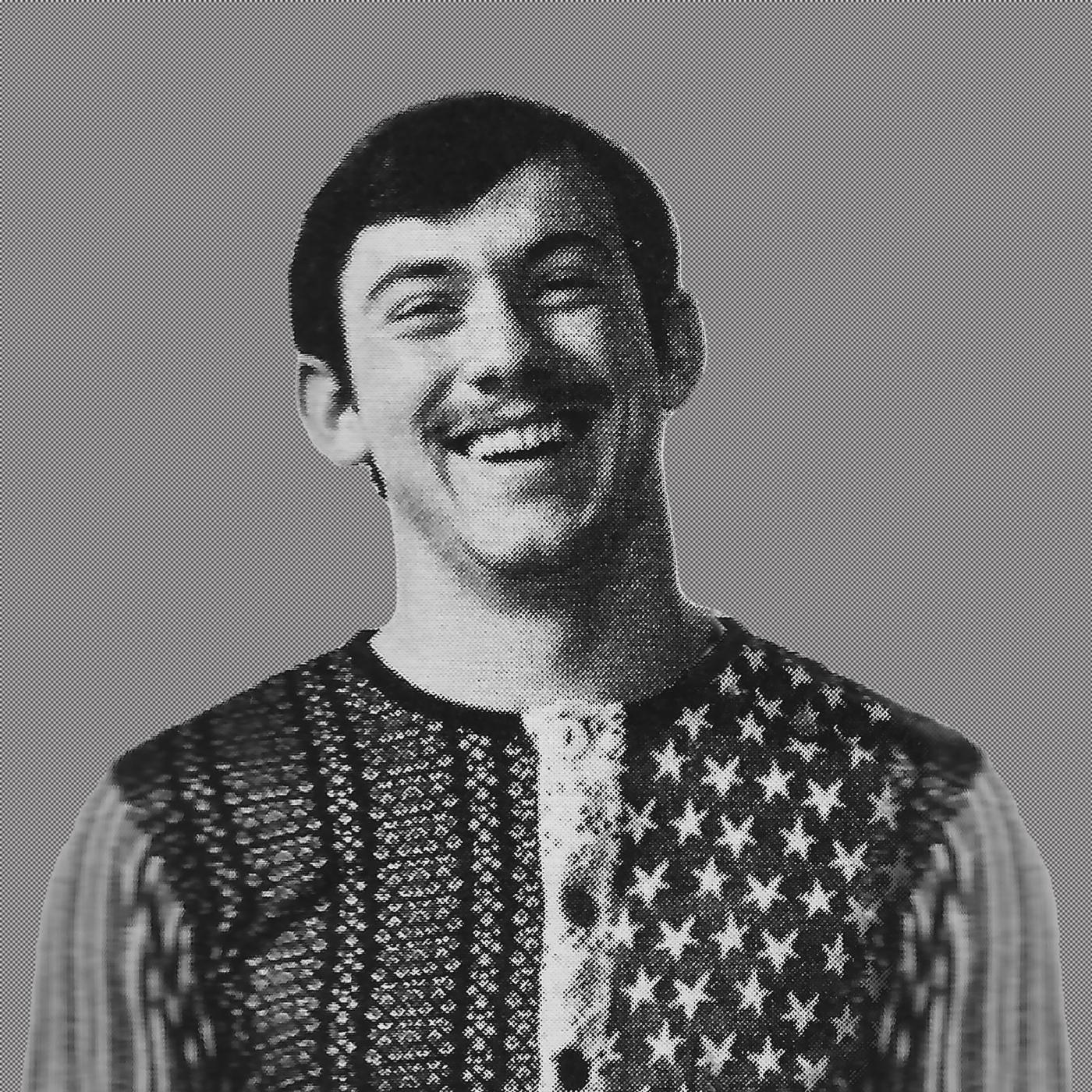

1. Ada Mallard Rachal (1898-1991)

Transcript

David Dollar: Hello again, David Dollar, this morning, visiting all memories with Ms. Ada Rachal. Ms. Rachal, we thank you for joining us today. Why don't we start things off with you telling us a little bit about yourself and your family and some history and things. Ada Rachal: Thank you. David Dollar: Okay. Ada Rachal: My father was named Nester Greeter, either your own layer styles, and they had quite a big family. They married, they lived together until death, for around 60 some years. David Dollar: Oh goodness. Where were they living at the time? In other words where- Ada Rachal: Right about in this neighborhood. Never did move far away until later. David Dollar: Right around Shady Grove, huh? Ada Rachal: Around Shady Grove, uh-huh (affirmative). He reared a big family. My mother was the mother of 18 children. David Dollar: Ooh, goodness. Ada Rachal: Five sets twins. David Dollar: Five sets of twins. Ada Rachal: Five sets of twins and four sets of- David Dollar: My goodness. Ada Rachal: Four sets of twins in succession. David Dollar: I can't believe that. Ada Rachal: It's real, though. It's real. David Dollar: Goodness gracious. Ada Rachal: Five sets of twins. And she had 18 children. And I'm thankful to say that reared, those children, and none of us are that in no serious trouble, and never had to go to jail. David Dollar: My goodness. Just by odds alone, out of 18 people, you could just about say, one of them at least, was going to get into some kind of trouble. Ada Rachal: That's right. David Dollar: But y'all managed to stay out of it. Well that's good. Ada Rachal: I always said I loved my daddy. I loved both of them. I love my daddy. He was very interested in children learning to read the Bible. He couldn't read other books. But the Bible, he could really read it. And he had a big dining table, he'll sit with us around the table two or three times a week, and how he got all the testaments he had, and the Bible story books, I don't know how he got them, but he had them. And he was sitting with us around the table and have us all read with him. Learning how to read the Bible. And he would explain it to us. Made a pretty good living, or some may call it a hard time now what we went through, but we all appreciated the things that our parent doing to us. David Dollar: Oh I bet so. Ada Rachal: And grow the nice crop, and planted peas and corn, and everything. David Dollar: What all were they growing then? Just things for, like vegetables or doing cotton too? Ada Rachal: Cotton, too. Big, big cotton crops. And we worked in the field. I learned to use every plow the boy use. David Dollar: Oh goodness. Ada Rachal: I plowed along with the boys. David Dollar: So there wasn't that much difference between the children there. Ada Rachal: It wasn't. The girls and the boys worked together. David Dollar: Not boys doing this and girls doing that, you did whatever needed to be done. Ada Rachal: You did whatever they done. Cut wood whole, pick cotton, plow, do all of those things. David Dollar: Goodness gracious. Ada Rachal: And I loved it. My mother was very conscious about seeing that we had a plenty to eat, regardless of what it was. If it was nothing but peas and bread. David Dollar: There's going to be enough of it there. Ada Rachal: Plenty of that. David Dollar: Right. Ada Rachal: And she was very careful in dealing with the children, wouldn't just treat one. She was a good seamstress. She could sew, make clothes on her fingers and do things like that. But the real thing that I loved to do was to go to school whenever I could, whenever that we had school. We didn't have but three months of school. David Dollar: Oh yeah? Ada Rachal: Uh-huh (affirmative). David Dollar: When did you have school? How old were you when you first started? Ada Rachal: I was six years old. David Dollar: Six, okay. Ada Rachal: I was six, mm-hmmm. David Dollar: And where was the school? Here in the community? Ada Rachal: Here in the community. Up there around [inaudible 00:03:38]. And we go to school. We go from old houses where it wasn't nobody living in. And we'd have school in a old house and in the church house. David Dollar: What about the teacher? Where did he or she come from? Ada Rachal: Oh, well maybe out of town, somewhere like that. David Dollar: I know I've heard, talked to several folks around here and other places, too, how the parents would have to get together and get up the money to hire the teachers. Ada Rachal: That's right. Sometimes. So we have public school. If it's got to be three months and if their parents seeing that they need children back in the crops, they would take them back in the crop. Maybe one of the trustees go in and talk with the school board member and tell them that they the need the children back in school, call it the vines and weed growing up in the corn and need to week it out. David Dollar: So they kind of worked with the teacher and the school board, too. Ada Rachal: Oh, they did. They did. We worked together. David Dollar: Well that's good. Ada Rachal: We went to school and I did love to go to school. I learned many songs in school. David Dollar: Oh yeah, like to sing. Ada Rachal: Just like to sing. We've had many different recreations of concerts, you know, have concerts, some called drill. David Dollar: Now wait. Tell me about these concerts. Do you remember any, you know, really well that you could kind of tell me about or tell all of them? Ada Rachal: So yeah. See we'd have a different...we'd have bloom drills in the concert or you the band drill. Or sometimes we have a flag drill and representing the United States. We'd have a flag drill. David Dollar: What did you do in these concerts and drills? Ada Rachal: Well, we'd go around in circles and go round when [inaudible 00:05:27] come in, he'd make it very beautiful. Look like it was very following. You know, you're going around. David Dollar: Kind of marching around. Ada Rachal: Kind of marching around. David Dollar: Yeah. Ada Rachal: Some go one way, some go, then they meet and get together and go around again. It was beautiful. David Dollar: Who drew all these together? Who put them together? Ada Rachal: The teacher. David Dollar: The teacher did. Well, my goodness. Kind of like the marching bands today, like at football games. Ada Rachal: That's right, that's right. Something like that. David Dollar: So y'all were doing that, huh? Ada Rachal: That's right, we were doing that, in fact sometimes I look at it now I say, "Oh, we used to do something like that." But wasn't using decent instruments at that time, we'd be singing. We didn't have no band and nothing to play. But we would sing and keep music with that way. You know, it makes me very instrumental, and I love that. And I still have some poems that I still remember, that I said when I was going to school. David Dollar: Can you remember one you can tell us right now? You remember? Why don't you do that? Ada Rachal: After school and I got married when I was 17 years old. And I had done said this speech before. And so, "I know a wee couple that live in a tree, and in they high branches, their home you could see. The bright summer came, and the bright summer went. Their [inaudible 00:06:36] gone, but they never paid rent. The parlor, whose lined, it was the softest of wool. That kitchen was warm, and their pantry was full. Three little babes peeped out at the skies, you never saw darlings so pretty and shy. When winter came on with his frost and his snow, they cared not a bit if they heard the wind blow. All wrapped in fur they all lie down to sleep, but always spring how the bright eyes will peep." David Dollar: Oh yeah. Well that is might good. When did you learn that? Ada Rachal: Oh, I learned that when I was about 15 years old. David Dollar: You've got quite a memory there. Ada Rachal: Oh, about 15 years old or whatever would go on in school, I would kind of keep it in mind and then songs I kept them wrote down, On the Blue Ridge Mountain of Virginia, Come on Nancy and Put Your Best Dress On. And another one, let's see, it's I Have Friend Far Away, Far Away. David Dollar: Just all of them. You really enjoyed all of that. Ada Rachal: Mandalay, Mandalay. Yes, I enjoyed all that. I rehearsed it very much after I was married. David Dollar: I'll tell you what we need to take a short commercial break right here. We'll be right back visiting with Ms. Ada, Rachal this morning, right after our message from People's Bank and Trust Company, our sponsor. Hello, once again, in case you've just joined us David Dollar, today down in Shady Grove, visiting with Ms. Ada Rachal. Ms. Rachal, we've been talking about school and work and family, and all that. I'd like to ask you a little bit more about the family. Now, when was it that you were born and how did, how are you age-wise in relations to your brother and sisters, all 18 of them or 17 others, I guess Ada Rachal: Well I was born in March 17, 1898. David Dollar: 1898, okay. Ada Rachal: 1898. And it was about five older than me. And I was a twin, my twin is still living. He's living in San Francisco. David Dollar: Well I'll be. Ada Rachal: His name is Lee [inaudible 00:08:49]. David Dollar: I see. Ada Rachal: And we was a set of twins. Five sets. And I was one of them. David Dollar: So you had all these twins. Was it very much trouble for your mother or for you keeping up with twins, aren't two new babies a lot harder to keep up with than one new baby? Ada Rachal: It didn't seem like it was hard because always some older. It's about three or four was older than the first set of twins. Then we would take care of the baby- David Dollar: So your mom always had help. Ada Rachal: Had help. We would take care of them. And after I grew , around nine or 11 years old, well, that was my job taking care of the babies, too. And then cook and feed the babies and cook for my father and mother while he was at work. David Dollar: So you're an old hand- Ada Rachal: I'm an old hand. David Dollar: At keeping up with children and keeping house, and- Ada Rachal: Then I did midwife work for about 41 years. David Dollar: Oh really? Ada Rachal: I did. David Dollar: Right around here? Ada Rachal: I delivered many babies around here, [inaudible 00:09:42]. David Dollar: Well, I'll be. Ada Rachal: I started working when I was 29 years old and I quit when I was 70. David Dollar: You had practice doing that, too, huh? Ada Rachal: It was just a gift God gave me. And then I had a book that I'd read and my mother a doctor book called A Family Book, and I read that book and learned how to do what it says how to treat them all, and they want to do. And I went about that. After going into the work, I got quite a bit of experience, and working with doctors, too, when they had to call the doctor in the home. And I worked right along with him. Man didn't need to tell me- David Dollar: Learned with him and help him. Ada Rachal: I worked so diligently with that, and loved the job so well to Dr. Reed, or from [inaudible 00:10:23] she says now, but he's wanted me to leave my work from home and follow him. Turned around said, "I'd make a registered nurse out of you." David Dollar: My goodness. Ada Rachal: And I was anxious to, but [inaudible 00:10:32] said, "No, I married you to take care of me and my business." So that's why I didn't go into that. [crosstalk 00:10:41]. David Dollar: Well that sure is interesting. Ada Rachal: I worked until I was 70. David Dollar: And without the up-to-date hospitals and transportation service we've got today, folks like you are very much needed in communities not real close to big hospitals like in [inaudible 00:10:55]. Lady had to have a baby, she couldn't get in the wagon and head for [inaudible 00:11:00]. Ada Rachal: Well at my age I would be very interested in helping out anywhere now. I loved it. I felt like that was my calling. David Dollar: I bet you help. A lot of people felt that was your calling to help them out and their babies. Ada Rachal: I'm sure I delivered around 500 babies. David Dollar: Oh goodness. That is something. Ms. Rachal, we're just about out of time Ada Rachal: And then in two or three families, I delivered all of their babies. David Dollar: The whole family, huh? Ada Rachal: They have 10 or 11 kids, and I delivered all of them. David Dollar: And you were there for all of them. Ada Rachal: That's right. David Dollar: Oh, goodness. Again, we're just about out of time. Let me ask you for your closing memory that you wanted me to remind you about your grandma. Why don't you tell us about that? Ada Rachal: Oh yes, I'll be glad to tell that. My grandmother, she was very good Christian woman. And she said God revealed to her that she had only five more years to live. Well she told that after the death of one of her grandchildren and she say, "Well, I got five more years to live." Said, "It has been revealed to me that I live five more years." And sure enough, at five years she passed. She had cancer. She had about five cancers, and she lived two years off and on, on the bed. And right up to the time she say she would leave us when she did. David Dollar: She knew what was going on. Ada Rachal: Yeah, she knew what was going on. I said, a person with a Christian experience, God do reveal things to them. And when we live close to Him, He's always with us and He will give us what to know, what He want us to do, and what's going to happen. David Dollar: Well, amen. That's a very fine closing memory and the whole visit this morning has been quite nice. And we thank you for sharing all this with us today. Ada Rachal: Yeah. Thank you. David Dollar: Okay.

Ada Rachal: Her father taught her how to read and interpret the Bible. She and her family use to work in the field farming. She remembers her time in school and got married when she was 17 and is fond of poetry. She is a former midwife.