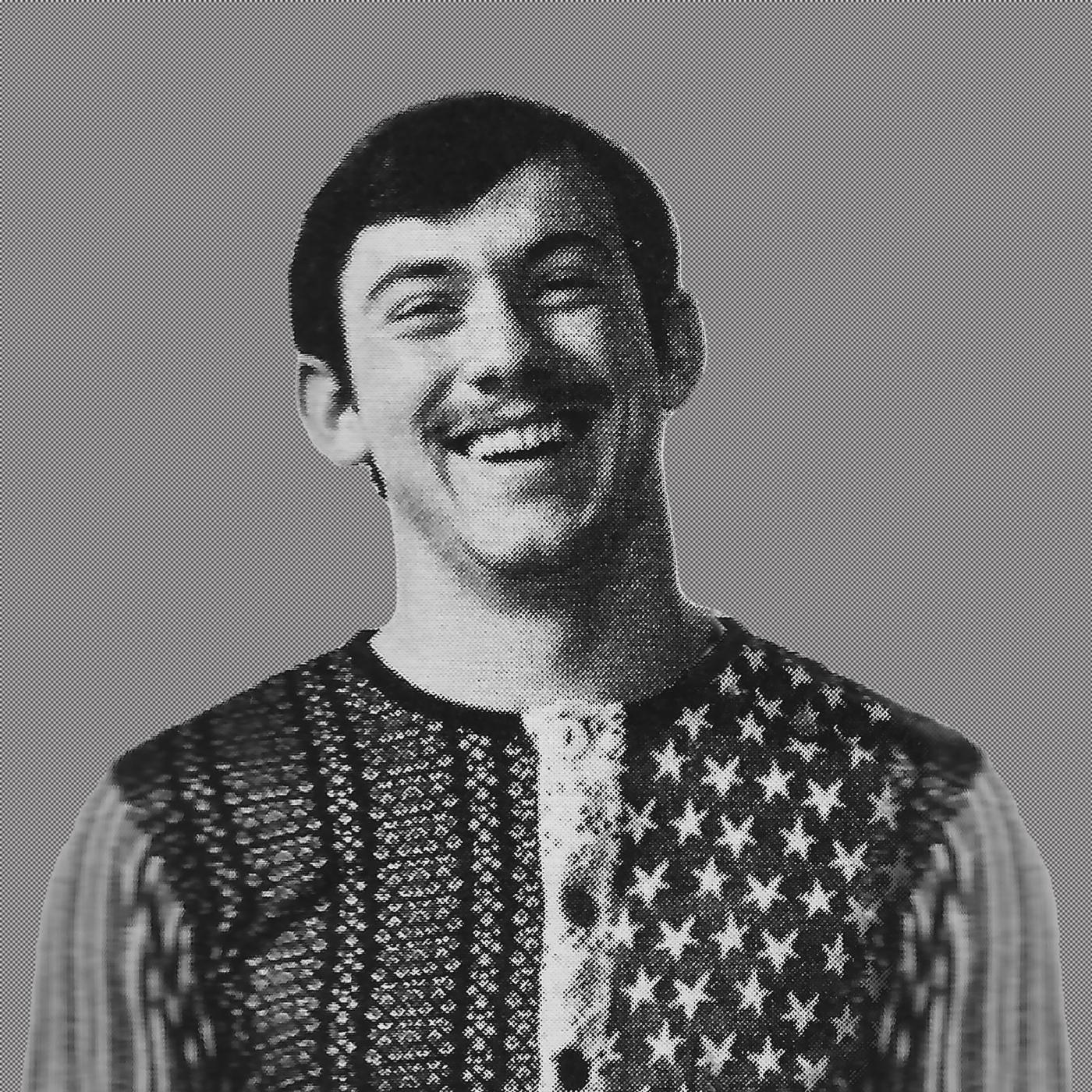

53. Gracious Prudhomme

Transcript

David Dollar: Good morning. This is David Dollar, and we're going to visit this morning on Memories. This is Gracious Prudhomme of Natchitoches, a retired schoolteacher, and we're going to begin our program right after this message from People's Bank & Trust Company.

Hello, once again. In case you've just joined us this morning, this is David Dollar on Memories. We're visiting in the home of Ms. Gracious Prudhomme of Natchitoches today. Ms. Prudhomme, why don't we start things off by you just telling us a little bit about yourself, when you were born and a little background information, how about?

Gracious Prudhomme: I was born on Boyd Street, February 6th, 1902. I was born there what we call a normal school at that time, which was a very interesting spot to be around because to see the children going back in the valley, it was really something.

David Dollar: About, in your estimation, I guess, about how many students attended here at that time?

Gracious Prudhomme: Attended normal school?

David Dollar: That came to the school.

Gracious Prudhomme: Well, I was very young at that time. I couldn't say, but I don't imagine it wasn't anything like it is now.

David Dollar: Bet so.

Gracious Prudhomme: But they had a lot of them up there. Children of all ages went there. Because they had the elementary and high school.

David Dollar: Oh really? I didn't know that. Well, they were producing teachers then too, weren't they? They forgot. So the kind of same situation as the lab school out there.

Gracious Prudhomme: That's right. Yes, sir.

David Dollar: What were your folks doing when you were born there growing up?

Gracious Prudhomme: Well, my father was a carpenter and my mother washed and ironed. At that time, they had no laundry at the normal and we didn't know anything about washaterias, so our mothers would wash for those girls up there and sometime they'd have a lot of them that the wash for.

David Dollar: Oh, I bet so.

Gracious Prudhomme: At that time.

David Dollar: I bet that again, at that time, that was quite a service to the young ladies, especially at the college too.

Gracious Prudhomme: It was quite a service.

David Dollar: Now.

Gracious Prudhomme: They had no way of doing their clothes like they do now.

David Dollar: Right. Yeah. We just take things like that for granted now. Got washaterias right off campus.

Gracious Prudhomme: That's right.

David Dollar: And even in some of the dorms,

Gracious Prudhomme: We didn't know what a washateria was at that particular time period.

David Dollar: And most families probably didn't have the washing machines, as we know with that.

Gracious Prudhomme: They didn't have them, at least we didn't know anything about a washing machine. They used the old wash tub and washboard at that time, and wash pots to boil in, you see?

David Dollar: Did you ever do any of that around the house?

Gracious Prudhomme: Sure, yes. Around the house. When I grew up, it was going on. And as I grew, well naturally I got into all hose things.

David Dollar: You inherited some of the work around the house.

Gracious Prudhomme: Yeah, I inherited some of that too. So if I couldn't iron, I could press. You see?

David Dollar: Right.

Gracious Prudhomme: I could help out like that.

David Dollar: And didn't you mention too that you had two brothers but no sisters?

Gracious Prudhomme: I had two brothers, and no sisters.

David Dollar: You got kind of stuck with the ladies work.

Gracious Prudhomme: That's right. That's right. Because they helped out with whatever was to be done around the house. Naturally boys helped in those days, just like the girls helped.

David Dollar: Just, if there was work to be done, it got done.

Gracious Prudhomme: There was work to be done and it was everybody's job to see that the work was done.

David Dollar: Do you think that's the same case in homes today?

Gracious Prudhomme: It should be. I don't know how far it goes now.

David Dollar: Maybe not.

Gracious Prudhomme: But everybody should feel responsible for the home and helping to keep up things.

David Dollar: I believe that, for sure. Tell me about going to school.

Gracious Prudhomme: Well, I started to school when I was six years old. One particular thing I remember my mother kept telling me, "Be sure you tell him you was six years old." And that's one thing that makes me remember that I was six years old.

David Dollar: Because your mother instilled it so much.

Gracious Prudhomme: You see instilled it in my mind when I started in Shiloh Baptist Church. The same church is down there. It's a different building, but the church still stands there. It's on 4th Street.

David Dollar: Down on fourth Street.

Gracious Prudhomme: And I can remember how crowded this church was and the grades must have been about first through fourth or something like that. But-

David Dollar: All the children were right into one church.

Gracious Prudhomme: All of those were in one church and they had two teachers there. I remember that well. My first teacher was Miss Ola Barlow. I remember her.

David Dollar: She must've made quite an impression on you.

Gracious Prudhomme: She did. She made quite an impression on me. And of course the upper grades went to a school that we now call, we used to call it Green Valley. Professor Thomas taught that school. That was the upper grades. And I guess when you get about fifth grade or something like that, you would go up there.

David Dollar: We need to take a short commercial break at this time. We'll come back and kind of pick up where we left off in just a minute. David Dollars on Memories is visiting with Mrs. Gracious Prudhomme, we'll be right back after this message from People's Bank, our sponsor. Hello once again. In case you've just joined us. David Dollar, visiting on Memories this morning with Ms. Gracious Prudhomme. Miss Prudhomme, we were talking about you attending school and we know that you're a retired teacher. How about talking a little bit about why you decided to go into teaching and start telling us about when you first taught?

Gracious Prudhomme: Well, I always thought from small that I would enjoy teaching, because some of the teachers that I had gone to, it impressed me very much about learning and about helping others. And I was encouraged through friends that would be a nice thing for us to do. We would start teaching and so we did.

David Dollar: How old were you when you first started teaching?

Gracious Prudhomme: Oh, I guess about 18, about that. At that time, we had no schoolhouses for colored schools. The only colored schoolhouse that I remember at that particular time here when I started the school was the Catholic school down on Truder Street. I attended there for a while and then, when I started teaching, well, we only had church houses or other houses to teach in.

David Dollar: And that was still around, what about 1920 to 1922?

Gracious Prudhomme: 22.

David Dollar: 25 somewhere in there.

Gracious Prudhomme: 22 or something, maybe a little bit earlier.

David Dollar: Where did you first teach? Was it in Natchitoches?

Gracious Prudhomme: I taught at Rockfold. At Natchitoches Parish.

David Dollar: Where is that in relation to today? That doesn't ring a bell for me.

Gracious Prudhomme: It's kind of hard to tell you, but it's down on what we call Old River. Part of Old River.

David Dollar: Okay. I know where Old River is.

Gracious Prudhomme: If you want to go down there, you know where the old dump used to be, past there.

David Dollar: Across the new bypass there?

Gracious Prudhomme: Like you going towards Holiday Inn. But then you will cut off on a short road before you get there.

David Dollar: Right. Oh yeah. And just it follows Old River down to the church out there.

Gracious Prudhomme: Yeah.

David Dollar: Okay. So was it that same church?

Gracious Prudhomme: No, that church, they tore it down. I think it's torn down, but I know they're not using it anymore. It's partly down anyway. They have a new church, a very nice brick church there.

David Dollar: But it was on that same site, so, that you first taught.

Gracious Prudhomme: Just right on that same site.

David Dollar: Tell me about your first day of school. The new teacher walking in, wanting to make a big impression on her students. What did you find waiting on you when you went into the school?

Gracious Prudhomme: Well, I found quite a few children, if I remember well, I had 132 children on roll.

David Dollar: My goodness.

Gracious Prudhomme: And we were in one big church house with a big wood heater sitting in the middle.

David Dollar: One heater in the middle?

Gracious Prudhomme: In the middle.

David Dollar: And benches to sit on.

Gracious Prudhomme: And benches to sit on. The children had no desks.

David Dollar: My goodness.

Gracious Prudhomme: And of course I was lucky to use that collection table for my desk, you see. But other than that, we only had a system for water and the children brought their lunches. We were unlucky like the children are now. They have a good hot lunch. At the time, you had to bring all lunches in paper bags and buckets.

David Dollar: And you were teaching all the elementary grades.

Gracious Prudhomme: All the elementary grades from first through eighth grade.

David Dollar: You had children that had never even seen an alphabet before all the way up to those who had learned to read and write and everything. That must have been a tremendous challenge as a teacher.

Gracious Prudhomme: It was.

David Dollar: To say the least.

Gracious Prudhomme: It was to have all those children and to try to get around to them all day.

David Dollar: I bet.

Gracious Prudhomme: But you see, if we had children in upper grades, they could help us with the little children in the afternoon, for instance. I could hear them all myself in the morning, but they did expect the little children to have at least two reading lessons a day. Well, then the children in upper grades could help out-

David Dollar: Would help you.

Gracious Prudhomme: With the little children.

David Dollar: That sounds like a good system and one that you would almost have to use because like you said-

Gracious Prudhomme: You couldn't get around.

David Dollar: You couldn't get around to every student. There's no way.

Gracious Prudhomme: Every one, twice a day like that, especially the small folks.

David Dollar: We are just about out of time on our show this morning. We like to close our show with what we call the closing memory. Why don't you share with us again about education that which we talked about a little earlier on the program?

Gracious Prudhomme: Well, I would like to say in the closing, I would like to encourage all the young people to go to school and to try to learn because they don't have the disadvantages that we had when we were coming along. They have good schools now. They have the chance to go to college at home, and they can use these things and this will make better men and women out of them if they would just hold on to it.

David Dollar: Words of wisdom for every young person, whether in Natchitoches Parish or anywhere else. Miss Prudhomme, we thank you for taking your time out and sharing with us these memories today. We thank you folks at home for joining us and The People's Bank for bringing it all to us. If you folks at home have memories that you would like to share or you know somebody who in your opinion does have memories and would like to share, maybe a relative or a neighbor, why don't you give us a call and tell us about it? We are able to go into homes now as we're visiting in Miss Prudhomme's Home today. The number of the retired senior volunteer program is 352-8647, and they're helping us get our taping schedule set up. We thank you again, Miss Prudhomme for having us in your home and you folks for joining us. David Dollar, visiting with Ms. Gracious Prudhomme on Memories. Have a nice day.

David Dollar interviews retired schoolteacher Gracious Prudhomme about growing up with two brothers, attending school as a child, becoming a teacher at 18, and her encouragement to young people.