Last updated: March 21, 2023

Place

Site of 'The Woman's Journal' Office

NPS Photo/Woods

As the most widely recognized suffrage journal in the United States, The Woman's Journal served as a significant tool to promote the suffrage cause.

First published in 1870, the Woman’s Journal announced itself as "devoted to the interests of Woman, to her educational, industrial, legal and political Equality, and especially to her right of Suffrage."1 This publication quickly became the leading suffrage journal to advertise local, national, and international news on women’s rights issues.

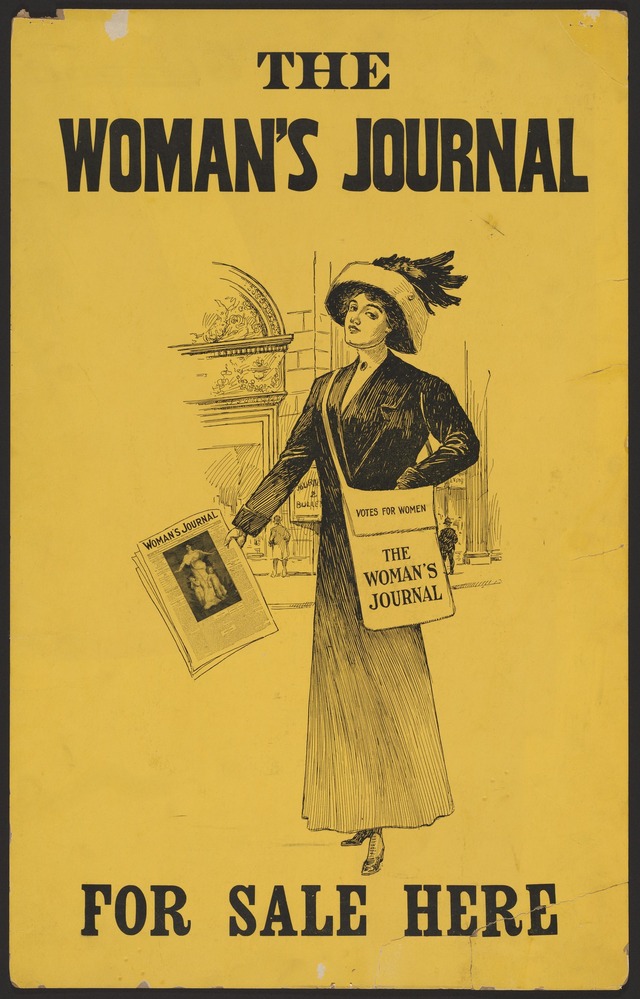

Poster advertising The Woman's Journal. (Credit: Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe College, Harvard University.)

Members of the Stone-Blackwell family—Lucy Stone, Henry Blackwell, and Alice Stone Blackwell—led the publication throughout its lifetime. Other editors, contributors, and supporters included notable activists, such as: Mary Livermore (first editor), Julia Ward Howe (contributor and early stakeholder), William Lloyd Garrison (contributor), Thomas Wentworth Higginson (contributor and early stakeholder), Agnes Ryan (later editor and board member), Florence Luscomb (later stakeholder and "peddler" of the Journal), and others.2

Since the publication's editors held leadership roles in the state, regional, and national organizations, the offices of the Journal often shared office spaces with other suffrage organizations. Its first offices occupied rooms at 3 Tremont Place; later office locations included 3 Park Street, 6 Beacon Street, and 585 Boylston Street.3

The final move to 585 Beacon Street resulted from the publication expanding its operations. Editor Agnes Ryan described how over the course a few years, the Journal went from a staff of three to a staff of 24 people and about 10 departments. She noted the excitement of working in the office, recalling an occurence after the 1915 failed state referendums on women's suffrage:

We find working in the Woman’s Journal office year after year is in some ways like living in a fairy story. We never know what is going to happen next. The day after election – and defeat in New York, Pennsylvania, Massachusetts and New Jersey—a woman came to the Journal office bearing a check for $1,000 in her hand and saying in substance. ‘Here is a small check to cheer Miss Blackwell and the Journal in the face of yesterday’s defeats at the polls.’ Here is an example of the way suffragists feel toward the Woman’s Journal. To them it symbolizes the cause.4

The Woman’s Journal ran until 1917, when it joined with other suffrage publications to become The Woman Citizen, published in New York.5

Footnotes:

- "The Woman’s Journal," The Woman’s Journal, January 8, 1870, Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University, https://iiif.lib.harvard.edu/manifests/view/drs:48852545$5i.

- Barbara Berenson, Massachusetts in the Woman Suffrage Movement (Charleston, South Carolina: The History Press, 2018); Agnes E. Ryan, The Torch Bearer: A Look Forward and Back at the Woman's Journal, the Organ of the Woman's Movement (Boston, MA: The Woman's Journal and Suffrage News, 1916).

- Lois Bannister Merk, "Massachusetts and the Woman Suffrage Movement" (Phd diss., Radcliffe College, 1961). Independent Historian Lyle Nyberg has tracked many of the locations of Boston suffrage organizations. For more information, please visit the webpage Suffrage Organizations of Boston.

- Ryan, The Torch Bearer, 45-52.

- See The Woman Citizen, https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/008868782.