Last updated: January 8, 2024

Place

Longfellow Bridge

Kate Hanson Plass

Public Transit

The chief monument of the Charles River Basin and the structure which does more than any other to formalize the planning of the river is the Longfellow Bridge, designed, the bridge commissioners wrote in 1900, "to furnish the eastern boundary of a great park system along 18 miles of river...destined to be the most beautiful park in the country. It is the present purpose, to make the new Cambridge Bridge one of the finest and most beautiful structures in the world." The Longfellow Bridge was authorized by the same 1894 legislation which authorized the Boston Transit Commission, the Tremont Subway, and the Charlestown Bridge. Like the Tremont Street Subway, the Longfellow Bridge was in large part a result of heavy streetcar congestion brought about by the increased traffic of the new electric cars. The old West Boston Bridge, constructed in 1793 and rebuilt in 1854, had been on the very first route to carry horsecar traffic, in 1856. Originally known as the Cambridge Bridge, the present structure was begun in July 1900 and completed in 1907, named for Cambridge poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow in the centennial year of his birth.

Though not the original structure, in 1855 the bridge into Cambridge played a role in the fugitive slave case of John Jackson. Escaping enslavement in Virginia, Jackson settled in Boston and found work on a coasting vessel. However, after being in Boston for a couple of weeks, Jackson’s former enslaver learned of his whereabouts and sent slave catchers to apprehend him. According to The Liberator, while walking home from work in January of 1855 Jackson, “was accosted by a white man who, from the description given, answers very well for a noted slave-catcher of this city, and asked if his name was not Jackson.”1 Jackson refused to give his name and, when pressed about his home address, Jackson lied, telling the slave catcher he lived in Cambridge.

Believing this lie, Marshall Asa Butman hoped to catch Jackson on his way to work. The next day, as reported by The Massachusetts Spy, “Notorious Asa O. Butman was seen to take a position upon the bridge early on Wednesday morning where he remained for about three hours.”2 Butman, the slave catcher that arrested Anthony Burns, did not get a chance to apprehend John Jackson. Jackson, with the aid of the Boston Vigilance Committee, left Boston and relocated to Worchester, remaining free for the rest of his life.

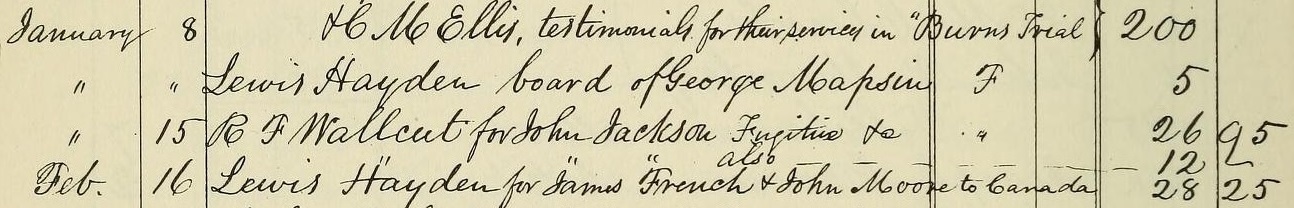

John Jackson received assistance from the Boston Vigilance Committee in January, 1855. (Credit: Account Book of Francis Jackson, Treasurer The Vigilance Committee of Boston).

Footnotes

- "Another Slave Case in Boston!" The Liberator (Boston, Massachusetts), January 19, 1855.

- "Another Slave Case in Boston- Escape of the Fugitive," The Massachusetts Spy (Boston, Massachusetts), January 17, 1855.