Last updated: September 11, 2025

Person

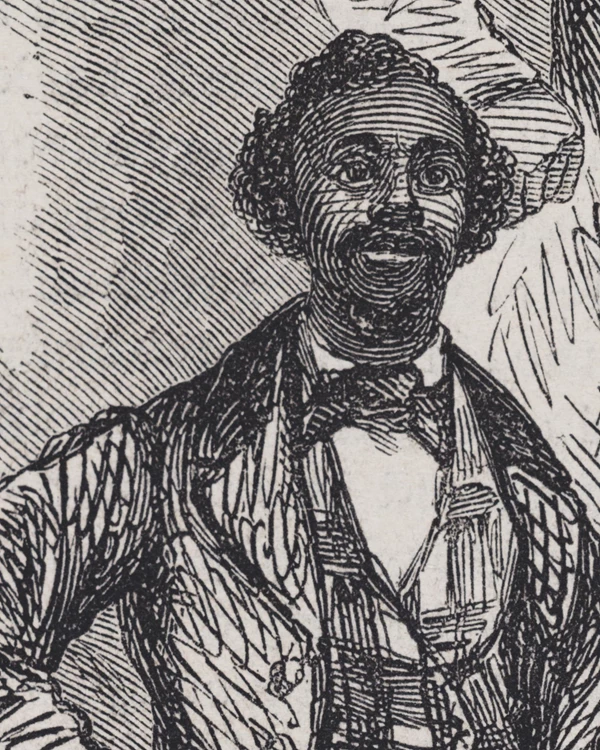

William C. Morrison

Library of Congress

A Forgotten Face of Reconstruction Era Beaufort

The story of an enslaved man in Charleston liberating himself aboard a stolen Confederate vessel, who came to Beaufort, purchased property, served in the military, owned a business, and was elected to political office – sounds like a familiar story to many in the South Carolina Lowcountry. However, most people have never heard of William C. Morrison.

William C. Morrison was born around 1820 in South Carolina. Little is known about his early life. By the outbreak of the Civil War, he was enslaved by Emile Poincignon as a tinsmith in Charleston. He had been married and had at least two children, but by 1862 they had been sold and were in Montgomery, Alabama, leaving Morrison in Charleston. In May 1862, the enslaved crew of the Planter, a small steamer Confederates used to move supplies around the Charleston harbor, decided to liberate themselves. One night, the white crew members went ashore – and Morrison boarded. Morrison was not a sailor but was likely friends with one of the regular crew of the vessel. The group sailed past the Confederate forts and turned themselves over to the U.S. Navy blockading Charleston. Morrison, the crew, and their families, were now free.

Admiral Samuel DuPont awarded prize money to the freedom-seekers for the value of the Planter. Believing him to have been a late addition to the endeavor, DuPont awarded Morrison the smallest prize of any of the men on board, only $384. Between May 1862 and March 1863, Morrison’s exact movements are unknown. He likely put his tinsmith skills to work in Beaufort and began to earn additional income. During the wartime tax auction in Beaufort, Morrison purchased a house along Carteret Street (the present-day rear of the downtown Beaufort Library). In March 1863, at the age of 43 years old, he decided to join the Army. He enlisted in the 2nd South Carolina Volunteers, later redesignated the 34th United States Colored Troops. Being double the age of a typical Civil War soldier, Morrison struggled with daily military life. Much of his military career seems to have been spent on guard duty and staying sick in the hospital. He walked with a noticeable limp from the effects of rheumatism.

On the night of June 1, 1863, Morrison saw several companies of the 2nd South Carolina loading up on transport ships for a recruiting mission on the Combahee River. He begged his commanding officer for permission to join them. The officer relented, and Morrison – for the second time in his life – boarded a late-night vessel bound for freedom. This time, instead of joining Robert Smalls, he was joining Harriet Tubman. Morrison’s company participated in the liberation of Newport Plantation during the Combahee Raid. At least three people liberated on the raid later testified on Morrison’s behalf as his family fought for a military pension in the late 1870s and 1880s.

Morrison left the army in 1864 under unclear circumstances. His age and health had been declining, and one of his officers detailed him to become a recruiter for the regiment, since he couldn’t do regular duty. At some point, he was told to simply go home. He never formally mustered out of the army, and army records eventually listed him as a deserter as of March 1864.

As the Civil War ended, Morrison decided to profit from the trade he had been forced to learn during enslavement. He opened a tinsmith shop in the property he bought during the wartime tax auctions. He was one of dozens of Black entrepreneurs in a thriving Black business community in downtown Beaufort, maintaining his business at least into the mid 1870s.

But this Planter escapee turned property owner, soldier, liberator, and businessman, was not yet finished. During enslavement, Morrison had secretly learned to read. This skill made him attractive as a political leader. In the state’s very first election in which Black men could vote – the residents of Beaufort elected William C. Morrison to serve in the South Carolina House of Representatives. He served alongside his fellow Planter escapee, Robert Smalls. Morrison served on the Roads and Ferries Committee and pushed for a bridge to be built across the Combahee River.

Despite their shared background on the Planter and in Beaufort’s Black business community, the two men did not get along. There was intense resentment between the two – after all Smalls’ share of the prize money was over $1,000 more than Morrison’s. Morrison and Abraham Allston (another of the Planter freedom seekers) both believed that Smalls had exaggerated his role in the escape of the Planter, and their disagreements spilled over into postwar politics. Morrison only served one term in the state legislature from 1868 to1870.

In 1870, Morrison and Allston signed an affidavit in opposition to Small’s candidacy for political office, and that was printed in the October 13, 1870 issue of the Charleston Daily Courier. In the 1872 election, Beaufort’s Republican Party split in two. Robert Smalls led a faction called the “Regular Republicans” and William Morrison chaired the “True Republicans,” which put up William J. Whipper as candidate for the state house against Smalls. Smalls and the Regular Republicans prevailed, and Morrison left politics, returning to run his tinsmith shop on Carteret Street.

Morrison’s emancipation story wasn’t without heartache though. It appears he was unable to reunite with his pre-war family who had been sold and sent to Alabama. It is unlikely he ever discovered what became of them. But by 1870 he had remarried a woman named Patience Barnwell, and they had several children, all born after the Civil War.

William Morrison died on February 25, 1879. After his death, his family fought for years to acquire a pension based on his military service. However, since his Army documentation listed him as a deserter, his widow’s pension claim was denied. As late as 1913, his son George was still corresponding with pension officials to clear his father’s name. Morrison is buried in the Citizens Cemetery across the street from Beaufort National Cemetery. He is one of the many forgotten figures of Reconstruction era Beaufort County. He was a freedom seeker, a liberator, a businessman, and a politician.

A note on sources:

Special thanks to Dr. Adam Domby, Kim Morgan, and Rich Condon for their research assistance. Morrison has received passing mention in books on Robert Smalls and Planter, and is mentioned as a politician in books on Beaufort history. But there is little secondary source material on him. Much of his story can be pieced together from newspaper articles and other primary sources. 1862 newspapers reported some of the early details of Morrison’s life, including his prewar enslaver, family, and occupation. Details about his Civil War and Reconstruction era experiences can be gleaned from his military service records, the pension application filed by his widow and children, newspaper and congressional records of his legislative career, as well as census records for him and his family.